Introduction

Strategic design helps medical institutions to restructure their services and organizational structures and meet the needs and demands of the external environment. Over the past two decades, there has been a growing tendency to replace the traditional static model with one that views the organization as a system. This new perspective stems from repeated observations that social organisms display many of the same characteristics as mechanical and natural systems. In particular, some theorists argue that organizations are better understood if they are thought of as dynamic and “open” social systems. Successful systems are characterized by adaptation, the capacity to constantly readjust to the demands of the environment. The organization under analysis is the private hospital in Kuwait.

Organizational Problem

The main problem faced by the private hospital in Kuwait is old-fashioned organizational structure which prevents it from growth and innovation. Two approaches will be used to redesign the hospital: start model approach and effective innovation system approach. Redesign may be required to meet changes in the organization’s core work. Sometimes that’s the result of an altered strategy. In other situations, the work is altered by new technologies or shifts in the cost, quality, or availability of resources (Drejer, 2002). A common example is the introduction of new technology in office systems.

Digitized information changes not only the way people perform individual tasks but the information-processing relationships; the configuration of computer networks, for example, plays a major role in either erecting or erasing boundaries between individuals and groups. The elimination of time and geography as barriers to shared work play a major role in determining organizations’ structures and processes (Dobson & Starkey, 2004).

To understand how the entire organization works, it’s essential to understand each of its important elements. Those include the input that feeds into the system, in terms of both its external and its internal environment. They encompass the strategies that translate a particular vision about how the organization will interact with its competitive environment into a series of concrete business decisions. They include the output — primarily, the offerings of products and services that the organization is required to produce to meet its strategic objectives. And of particular importance in terms of our model, they include the transformation process — the work and the business processes — that converts resources into offerings (Drejer, 2002).

The private hospital in Kuwait is influenced by a larger environment, which includes people, other organizations, social and economic forces, and legal constraints. More specifically, the environment includes markets (clients), suppliers, governmental and regulatory bodies, technological and economic conditions, labour unions, competitors, financial institutions, and special interest groups. The environment affects the way organizations operate in three ways.

First, the environment makes demands on the organization. For example, customer requirements and preferences play a large role in determining the quantity, price, and quality of the offerings — the products and/or services — the organization provides. Second, the environment often imposes constraints (Drejer, 2002).These range from limitations imposed by scarce capital or insufficient technology to legal prohibitions rooted in government regulation, court action, or collective-bargaining agreements. Third, the environment provides opportunities, such as the potential for new markets that results from technological innovation, government deregulation, or the removal of trade barriers (Dobson & Starkey, 2004).

Rationale for Change

The rational for change is low service quality and increased competition in this sector. The responsibility of every medical institution is to provide clients with high-quality innovative services which help them to recover. The second element of input is the organization’s resources. This includes the full range of assets to which it has access — employees, technology, capital, and information.

Resources may also include less tangible assets, such as the perception of the organization in the marketplace or a positive organizational climate. Environmental conditions, organizational resources, and history cannot be changed in the short run — these are “givens” that provide the setting within which the organization must operate. Each organization must first develop and articulate a vision of how it intends to compete and what kind of organization it wants to be, given the realities of the environment.

From that vision flows the strategy, a set of business decisions about how to allocate scarce resources against the demands, constraints, and opportunities offered by the environment (Drejer, 2002).

More specifically, strategy can be defined as explicit choices about markets, offerings, technology, and distinctive competence. Taking into consideration the threats and opportunities presented by the environment, the organization’s strengths and weaknesses, and the pattern of performance suggested by the company’s history, managers have to decide what products and services to offer to which markets and how to distinguish their organization from others in ways that will provide sustainable competitive advantage. Then these general, long-term strategic objectives must be refined into a set of internally consistent short-term objectives and supporting strategies (Dobson & Starkey, 2004).

The other reason for redesign is size. When organizations like the private hospital are relatively small, when most people know each other, and when the relationships are face to face and personal, many of the mechanisms for motivating, improving, and changing behaviour can be informal. Critics suppose that there is no need to spend time, effort, and energy in the creation of formal structure. As the private hospital grows, these informal changes may get overloaded or overburdened.

As new tasks and strategies are taken on, the formal changes may no longer be congruent with the rest of the medical institution. By no means do we mean to imply that operational design is not important; indeed, it is a critical aspect of design. And as we proceed with our discussion of strategic design, we will frequently refer to related operational design issues and explore how to link the two (Drejer, 2002).

The grouping will help the hospital to change work functions, positions, and individuals into work units. This technique will introduce into a structure involving units, departments, divisions, groups (Gardiner, 2005). The group becomes an identifiable subculture of the larger organization, and the sharing and processing of information becomes easier. But the boundaries inevitably become barriers, making it more difficult to share information outside the group and often engender conflict, competition, and a lack of cooperation among groups (Dobson & Starkey, 2004).

Grouping by activity will bring together employees who share similar functions, disciplines, skills, or work processes. In traditional functional organizations, for example, everyone involved in manufacturing is grouped together, as are all the people involved in product development, marketing, and sales. Grouping by activity also applies to the element of time. Beyond normal workflows, organizations sometimes experience situations characterized by abnormally high degrees of task interdependence; these include emergencies, crises, short-term projects, and one-time efforts aimed at resolving important problems that require participation from throughout the organization (Gardiner, 2005).

These are situations in which units that normally pool their resources suddenly have to work together with much closer coordination. Going back to our branch banks, for example, if a power blackout were to hit one part of town, branch banks in the unaffected areas would have to work together to deal with the emergency. Temporary alterations in interdependence frequently occur when product divisions that share similar technologies or knowledge bases are asked to join forces on a particular corporate venture that requires the combination of their resources and particular skills.(Dobson & Starkey, 2004).

Proposed Changes and Improvements

For managers, these decisions about offerings, markets, and competitive advantage are crucial. Organizations that make the wrong strategic decisions will underperform or fail. No amount of organization design can prop up an ill-conceived strategy. By the same token, no strategy, no matter how dazzling it looks on paper, can succeed unless it’s consistent with the structural and cultural capabilities of the organization.

The manager’s challenge, consequently, is to design and build an organization capable of accomplishing the strategic objectives. In practice, strategy flows from a shared vision of the organization’s future — a coherent idea of its size and architectural shape, its competitive strengths, its relative position of leadership in the market, and its operating culture. Beyond the general view of the future, however, strategy is closely linked to specific, measurable objectives. The guiding aspirations are moulded into a strategic intent — a set of specific goals that must be reached if the organization is to fulfil its guiding vision (Gardiner, 2005).

For the manager involved in organization design, the central issue is the identification of “performance gaps.” That entails a comparison of the specific objectives articulated in the “strategic intent”. The “gaps” help spotlight those activities where output is falling short of objectives and provide essential guidelines for figuring out where in the organization the redesign efforts need to be focused.

Organizations constantly face changing conditions. Consequently, effective managers must continually identify and solve new problems (Grant, 1998). This entails gathering data on performance, matching actual performance against goals, identifying the causes of problems, selecting and developing action plans, and, finally, implementing and then evaluating the effectiveness of those plans. Any organization’s long-term success requires ongoing problem-solving activities along these lines. In practice, once the work requirements are defined, managers tend to gravitate toward the formal organizational arrangements as the most obvious tool for implementing change. Why?

First, structural arrangements are substantially easier to modify than either individual or collective human behaviour. Except in new organizations, a manager usually inherits a group of people. There are limits to how extensively and quickly their attitudes, values, skills, and capacities can be changed. Similarly, there are limits on the extent to which people can be replaced or reassigned. Recruiting new people is time-consuming — and risky.

Moreover, filling major positions from the outside undermines the psychological contracts, or implicit understandings, that people have about their career advancement and job security. Even in the best of situations, significant changes in the composition of organizational groups takes a substantial amount of time (Dobson & Starkey, 2004).

The second reason that managers are drawn to formal organizational arrangements as a tool for change is that modifications in structures and processes can directly alter patterns of activity, behaviour, and performance. Indeed, the formal organizational arrangements can profoundly influence the other components, both directly and indirectly. For example, formal job definitions, hiring processes, and training programs can, over time, significantly shape people’s capacity to perform various tasks. The organizational structure, the composition of key advisory groups, and the design of the measurement and rewards system can greatly influence how people perceive and perform their jobs (Grant, 1998).

Leaders of all kinds will be models to guide their decisions about the best way to structure their armies, churches, governments, mercantile groups, or what have you. They will be looking for the “one best way” to structure an organization. They will develop models composed of sets of rules, such as the notion that the ideal span of control is six subordinates. Jobs should be kept simple so that workers could be interchangeable; decisions would be made at the top of the organization, while people at the bottom automatically carried out those decisions (Grant, 1998).

Most important for the private hospital is that design shapes the patterns of information processing. In a sense, information processing has become the single most important function within any organization (Grant, 1998).

There’s only one thing you can point to that everybody needs, everybody uses, everybody consumes or generates — or both — in the course of his or her daily work, and that’s information — information about markets, resources, Output, behaviour, procedures, processes, and performance. Any given pattern of organization arrangements will collect, channel, and disperse information in certain ways. It follows, then, that the key to design is constructing information-processing patterns within an organization that most closely match the information-processing requirements of its work (Mintzberg et al 2004).

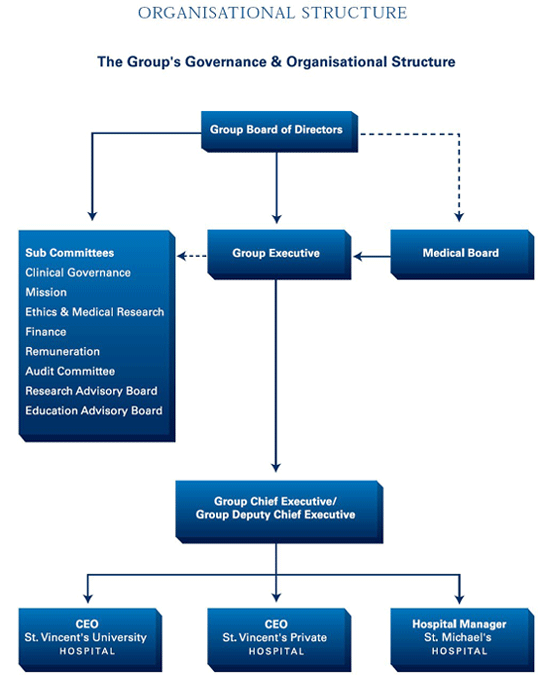

It is expected to create a matrix organization which structurally improves coordination by balancing the power between competing aspects of the organization and by installing systems and roles designed to achieve multiple objectives simultaneously. For example, an R&D facility that wants to maximize both disciplinary competence and product focus might design a matrix structure, with directors of the different laboratories reporting to both disciplinary and product managers. The president of each operating company has two bosses, a country manager and a business area manager (Mintzberg et al 2004).

Structural linking is an important managerial tool. Whereas a single form of strategic grouping is selected for each level of the organization, there may be a host of structural linking mechanisms within a single unit (Dobson & Starkey, 2004).

Possible Difficulties

A major redesign disrupts normal activity and undermines routine management control systems, particularly those embedded in the formal organization. Managers begin to feel that they’re losing control. (Mintzberg et al 2004). As goals, structures, and people enter the transition state, it becomes increasingly difficult to monitor and correct performance. Moreover, because most management and control systems are designed to maintain stability, they’re inherently ill-suited to managing periods of change.

Our experience makes it clear that there are specific things managers can do to counteract each of these change-related problems. These tactics don’t necessarily guarantee success; rather, they represent common actions taken by many of the organizations that manage effective change (Mintzberg et al 2004).

In practice, operational design and planning for implementation, rather than being separate processes, are sometimes assigned to the same group. That’s fine, as long as that decision is made deliberately and the appropriate people are given the resources they need to complete an adequate operational design. While not an explicit step in strategic organizational design, it’s useful for the team to compile its completed analysis in a design document (Mintzberg et al 2004).

Particularly during major redesign projects, this information can prove invaluable; the people involved in operational design and implementation may not have been involved in the strategic design process and may therefore have never seen the data underlying the design team’s decisions. If the design team has been diligent throughout the process, all that remains is for it to prepare a brief narrative to accompany the documents produced during the course of its work.

Lack of skills and knowledge will be the main problem. There’s a distinct parallel here between the architectures of technology and of organizations. The concepts of hardware and software apply to both. In organizations, the formal structures and processes are the equivalent of hardware — the boxes, chips, and operating systems that provide the computer’s information processing capabilities. But it is the people and the culture — the software -that bring the boxes and lines to life and dictate the form and content of the information that’s processed. Hardware and software are useless without each other and ineffective if mismatched. The same is true of formal structures and informal cultures (Mintzberg et al 2004).

At the private hospital, reactive changes, on the other hand, come much later in the disequilibrium period. They’re generally associated with a crisis atmosphere, little lead time, substantial costs, few opportunities for experimentation, and a high risk of failure. Clearly, it’s vital for managers to understand the nature of the change in which they’re about to engage. Each type of change is driven by a distinctly different design intent, which, in turn, dictates a cascading set of decisions about grouping, linkages, processes systems, and culture, as well as about the implementation and management of those changes.

As time passes, market leaders become increasingly arrogant and complacent. The more successful they are — the more dominant within their industry or business — the more they come to believe that what happens outside the organization can’t possibly be important. They start to ignore changes among customers and competitors. The inward focus grows, with disproportionate attention to internal politics and power. As success becomes taken for granted, the risk of failure becomes increasingly unacceptable; people grow cautious, experimentation stalls, and innovation dries up (Dobson & Starkey, 2004).

In time, the arrogance, insularity, complexity, and conservatism of successful companies lead to some predictable outcomes. Those characteristics squelch innovation, diminish speed, inflate costs, and diffuse customer focus. In short, they produce a seriously dysfunctional organization. During relatively stable periods, successful companies can rumble along with reasonable success despite those problems. But during times of dramatic change — the periods of disequilibrium — those shortcomings become critical, manifesting themselves in poor performance, falling market share, stalled growth, and a sharp decline in earnings.

At this point, executives typically engage in deep denial (Mintzberg et al 2004). They blame outside forces — government regulators, unfair competitors, gouging suppliers. They blame the economy, interest rates, and trade barriers. Unfortunately, one aspect of the dysfunctional organization is its inability to learn from its mistakes; it just goes on making the same ones (Dobson & Starkey, 2004). The emergence of an industry standard or dominant design signals an important shift in strategic emphasis from major product innovation to more incremental product change and process innovation. Organizations begin to segment markets on the basis of incremental product differences and reduced costs.

Conclusion

The change and redesign activities are crucial for the private hospital in Kuwait because they will help it to compete with other hospitals and provide patients with high-quality services and products. These processes coordinate workflow — the movement of products, services, and resources through the organization and across grouping boundaries — in order to create an offering of value to the customer.

More and more organizations are coming to perceive product development, for example, as a cross-unit process rather than as the exclusive domain of a single department where scientists and engineers work in a vacuum to dream up new products divorced from any timely insights into market trends or customer needs. Increasingly, product development is being seen as a continuous feedback loop, with sales, marketing, and service people working closely with the units that design, produce and distribute goods and services; it is a multidimensional process that draws on the skills, experience, and information of numerous people from a wide range of functions and disciplines.

As products become more standardized, companies shift their focus to process innovation as they seek competitive advantage through efficiency. Marketing, R&D, and production all assume increased importance during this phase. As new markets open up, companies respond with increased specialization, which in turn calls for more complex and interdependent organizational designs.

With increasing complexity, size, and volume comes the need for more professional management than the original entrepreneurial organization could provide. Nevertheless, the notion of architecture as a framework for organizational design and the fundamental concepts we’ve presented concerning the function, development, and implementation of design are essential tools for any manager hoping to guide an organization through this new era of perpetual change. Without those underlying ideas and guiding vision, managers are left to frantically steer an uncertain course from one crisis to the next.

Strategy sets organizational priorities and dictates which issues and concerns need to be managed most closely. For example, if markets are uncertain, competition is stiff, and customers are varied with different needs, then user groupings make the most sense. If, on the other hand, innovation in certain product niches is the priority, then it might be most effective to organize around output. If the most pressing strategic issues are cost and efficiency, then grouping by activity or function might be most appropriate. The case of private hospital in Kuwait shows that at most organizations, there are always some design experiments in the works. They may be going on informally, at a low level or on a small scale, but it’s unusual to find a company where someone, somewhere isn’t trying something new.

Bibliography

- Dobson, P., Starkey, K. 2004, The Strategic Management: Issues and Cases. Blackwell Publishing.

- Drejer, A. 2002, Strategic Management and Core Competencies: Theory and Application. Quorum Books.

- Gardiner, P. 2005, Project Management: A Strategic Planning Approach. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Grant, R. M. 1998, Contemporary Strategy Analysis, (3rd edn.). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Mintzberg, H., Lampel, J. B., Quinn, J. B., Ghoshal, S. 2004, The Strategy Process. Pearson Education.