Introduction

The structural and cultural suggestions of implementing inter-organizational addition and partnership are emphasized by some scholars in this field. Bielski (2005) e.g. reminds us, “that there are a number of managerial and cultural obstructions to overcome to implement collaboration.” According to him, people often resist new procedures. Similar to Cummings (2005) and Kay (1995) he sees the sharing of data or handing off possession of data to others “as the project moves through various phases of the product development” as a possible cause for disagreements.”

Moreover, he reminds that “Groups that formerly operated independently may resent having to co-ordinate their actions with others and that work styles and customs may vary between companies located in different areas around the world.”

Malaty (2004) in the same context underlines, that “joint product design, in a virtual plan surrounding, particularly entails the need for a lofty level of frankness and trust for best results. He terminates, that ‘on the road to success…, concentrating on cultural matters may be as imperative, or more significant, than technological explanations.’ The significance of taking cultural and managerial inferences into account is also maintained by an end-user study of Product Data Management (PDM) users. The following was found:

- Those organizations with strong information arrangements and lines of the announcement are more apt to apply –and are more flourishing when doing so.

- Despite users’ feelings about the power of data networks within their company and how well their PDM operations are succeeding, they still see the corporation’s structure and culture as the biggest barricade to development.

Being in line with these findings Doppler and Malaty (2004) remind that implementing structural change by switching to a network organization is an essentially different way of imminent tasks together that requires “radical structural transformation.” For successfully transforming the organizational structure they suggest that the commercial culture has to be modified to one that is based on honesty and trust.

Top reasons/ prerequisites for success (proposed and implemented by Nokia company):

- To listen to the right people.

- Not only think and get to know, but act.

- Do not waste time without reasonable cause.

- Avoid dirty bids.

- Do not listen to the “Big guys”.

- Stay calm and cool-hearted in any situation.

- Knowledge is power.

- Company should gain access to an expert with over 30 years of knowledge in individual and professional development.

- Company should get an expert who provides training and program content that makes people think.

- Company should get an expert who speaks with an audience.

- Company should get a specialist with the skill and desire to convert content to fit its specific needs along with a guarantee.

- Company should get an expert who is excited to invest the time and energy to discover the unique needs and wants of your attendees to deliver useful, targeted, useful, and “performance-enhancing” training. As a result, your team becomes inspired and equipped to be more effective, efficient, and fulfilled with a stronger sense of purpose.

- Company should get an expert who promises a lot.

- Company should get an expert who understands how exploring and honoring personal values can empower, motivate and stimulate passion.

- Company should show its people and team that are interested in building them. They’ll appreciate and value your desire and spirit to help them grow and hone their skills and expertise, which in turn helps your organization or company achieve unparalleled success.

- Company should demonstrate that it has the vision and integrity to strive for Excellence – which is much more than just bottom-line or profit-oriented.

- Company should indicate that you’re committed to long-term relations with the employees and team members.

- Company should help to create a “win-win” attitude in the team who starts realizing that for them to get what they want, it’s in their benefit to help their organization get what it wants.

- Company needs to progress toward having its mission statement become alive and permanently reside in the hearts and minds of its people. The mission statement is no longer just a slogan hanging on the wall behind your receptionist or printed on your business cards. Your living mission statement helps provide meaning and purpose to the workers, customers, all stakeholders, and their families.

- Company can expect more innovation and involvement. As core values are determined, defined, clarified, and lived daily, people start treating the company as their own.

- Company will also attract more people it wants on the team. Employee turnover is reduced because the company becomes known as a company where it’s about people first. Who would want to leave?

Change Management

To begin with, it is necessary to mention, that changes are the best way to improve the activity of the company. That is why these factors are included in the separate chapter.

It constantly works to meltdown confrontation. As change is being realized, he or she must continue to find ways to solidify consensus and manage the consequences and effects of transform within the company. Change agents must juggle a number of skills. They must realize, but not contribute to, a company’s politics. They must be able to “deconstruct” an organization or procedure and put it back together in unique, pioneering ways. They must be keen analyzers who can obviously and convincingly protect their analyses to the corporation.

They need to talk many organizational languages such as marketing, finance, systems, etc., and they must realize the financial impacts of change, whether brought on by a more sweeping overhaul or incremental incessant developments. In essence, they must bring order out of chaos. They do this by putting jointly solid teams encompassed of high-energy, qualified, and eager workers. A strong sense of mission, good communication skills, and a flair for the offbeat and unorthodox round out the change agent’s character.

Successful implementation management reform initiatives usually include:

Winning Leaders use a range of tools to hearten the direction of a result. Employee incentive and answerability mechanisms are allied with the goals of the association. Such leaders take steps to build the essential expertise and skills. They view training as an investment in human capital rather than an unnecessary expense. Dependable with quality organization standards, organizational learning must be continuous so that skills are kept up-to-date and changing customer needs are always met.

They incorporate the completion of separate organizational improvement efforts. Financial reforms may be self-initiated, mandated by Congress, while others may be administrative initiatives, such as the National Performance Review. Top leadership knows how to meld these various reforms into a coherent, unified effort so that they are adjustments that can easily be adapted to the performance-based management culture already in place.

Cultural resistance. Cultural resistance to transformation and parochialism can play a critical role in hampering financial management reform efforts. Many current operating practices have a long, entrenched technical history, and have developed gradually over time in order to contain the needs of different companies. The more deeply rooted these systems and manners, the more difficult they complete transform. Such change is unlikely to be instant; therefore, strong leadership is necessary to sustain a long-term commitment to performance-based management and other financial management reforms.

Unclear goals and performance measures: lots of agency directors lack clear, hierarchically-linked roadmaps that offer simple illustrations of how their work donates to attaining strategic goals, which can be complex by poorly integrated secretarial and data systems.

Lack of incentives for change. For lots of agencies, performance is measured by the amount of money spent, people employed, or tasks completed; however, increased concentration should be paid to prizing performances that meet planned, results-grounded aims.

Implementing organizational and cultural change is described as difficult, time-consuming, and costly (Herman, 1996) and therefore the result of Makin’s study (2004) that only one-third of major change proposals is winning is not very surprising. Lots of theorists and practitioners alike are proposing the consumption of Change administration techniques to successfully deal with the change process. Change Management that aims to provide an implementation and change-friendly setting within an organization (Rogers, 1997) has been and still is one of the most popular topics in business management.

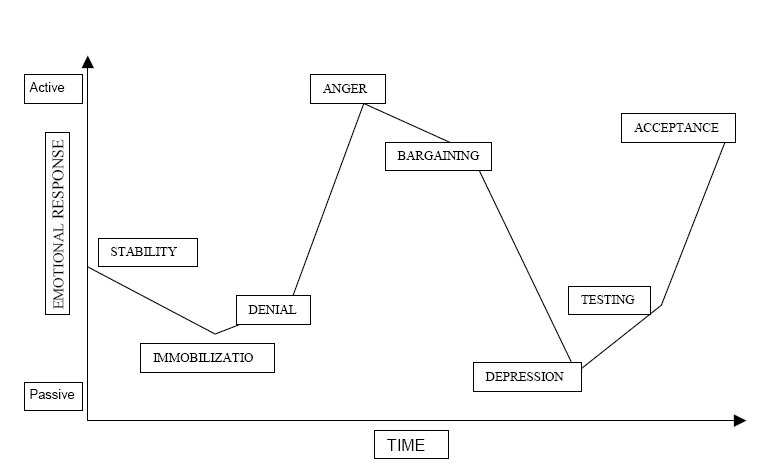

Many books and articles have been written about Change Management including well-known business researchers like Tsao, Tantoush, and Shaver. The roots of Change Management can be found in the science of psychology. Many of the techniques helping people to deal with traumatic emotional issues have been applied to “help stakeholders deal with thespian changes in how they make their employments”. The nature of change has been described by Kelley (1987).

He researched the stages that terminal patients and their families go through he developed a model (Figure 2.1) that explains the moving response during a alter process that is regarded as downbeat. According to Conner (1996), this model can also be functional to organizational change.

The Nature of Change

The frame (2002) suggests that there are dissimilar types of change that need different organizational strategies, advancements, and methods. In a commerce context therefore the scope of Change organization ranges from planned developments and reforms to business alteration. Top-Down approaches like business transformation (i.e. Business Process Reengineering or crisis management) are featured by a high quantity of intervention whereas bottom-up approaches like planned evolution or reforms (i.e. organizational development) are characterized by less intervention and by harmonizing the goals of the corporation and the affected employees

Conventionally the change process was explained as moving from a stable state through the rickety state of changing to the preferred state, being stable once more. Pennel (1989) characterized these three stages as: ‘unfreezing, changing and refreezing’ the organization.

Lots of researchers, though, emphasize that due to the financial environment of constant and increased speed change the stable states of organizations are becoming shorter (Rogers, 1997) or even diminish. Consequently, researchers remark that there also has to be a constant change process within an organization and that the change process has to be viewed as learning. In order to ease a constantly changing corporation, the focus is therefore laid on changing the organization into a so-called ‘learning organization’.

Conventional reactive models aim to react in an optimal way to changes that are forced from the environment, like technological or legal changes. In contrast hereof proactive models like learning organizations moreover aim to anticipate change and to generate change from within the organization. People are not being changed, they change in this context, that “the only bloodthirsty advantage the company of the future will have is it’s managers’ ability to learn faster than their competitor.” self-determining of the method that is used the capacity of an organization to change is viewed as a critical success factor and imperative corporate asset in a world of accelerating and constant change.

What Does “Change” Mean?

There are two types of change that challenge and impact companies:

- Internal— prearranged shifts or programs that are a continuing occurrence within a company. These changes may be undertaken to avoid worsening of current presentation or to improve the further presentation of a process or system. In this sense, they are managed and managed from within the association in an orderly, planned, and methodical way

- External— environmental modifications that come from outside the association, and the association exercises little or no organization over them. In commerce, this could mean shifting monetary tides, new entrants, or radical knowledge enhancements. In government, it can mean changes in the world circumstances, the administration, legislation, budgetary issues, or management reform.

The role of Change Management

The completion of an enterprise-wide information system will always mean a change to a certain extent, no matter if and to what degree it challenges existing culture, structure, and processes. Therefore Change administration can play a significant role to help to manage the changeover. The degree of change of course depends on the execution strategy. Accordingly, the Change organization tools and processes will vary depending on the accomplishment approach. The success or failure of PLM will to a great extent be resolute by accomplishment issues and especially by those that are dealing with the so-called soft factors like human behavior and attitude.

Confrontation of users and middle management as well as putting too much focus on scientific aspects and not enough on people narrated issues belong to the main matters of a PLM execution whereas the early participation of affected people belongs to the main success factors. Senior Management seems to play an especially important role. Their engagement and support throughout the whole implementation process are viewed as an important prerequisite for the implementation’s success. Contact through various channels and in different ways plays an imperative role to gain reception and to involve and integrate employees whereas workshops as an effective but inefficient way of communication are mostly used

Appropriate Change Management methods and tools

In this section Change Management tools are introduced that are arising from the research results respectively the interpretation of them and therefore seem to be appropriate for a PLM implementation.

- Diagnosis: Diagnosis is a significant tool to evaluate the present state and condition of a company in order to have a clear basis for defining the opposite action. A diagnosis can be based on a worker survey or on interviews carried out for the whole company or for a spokesperson cross-section. Since secretarial culture seems to play an important role, the diagnosis can aid in determining the predominant culture and defining the target culture. To ensure impartiality the diagnosis should be done by an outdoor institution.

- Senior management: Senior management seems to be one of the most critical success factors during a PLM implementation. Commitment and (vocally and visibly) support during the whole implementation phase seems to be critical. This can i.e. mean that senior management writes about the importance of the PLM implementation in the internal newspaper or by frequently visiting the implementation team. though not directly arising from the survey but from the interviews, it is important that senior management is ‘walking the talk’65 and serves as an example. In practice, this can mean that senior management has to show collaborative behavior when collaboration is one of the goals of the PLM implementation. Therefore it is important to create awareness at the senior management level about their important role during a PLM implementation

- Communication: Communication throughout the whole change process has mainly two goals. The first goal is to explain why the changes are necessary and what the aims are in order to address initial fears and resistance. The second is to involve the people that are affected by the changes as early as possible to gain acceptance. In the context of PLM, this can mean that PLM is introduced in the internal newspaper or in the Intranet. Although these are very efficient one-way communication vehicles a more effective two-way communication vehicle would be workshops or employee surveys where feedback from employees can be gathered.

- Coaching: Coaching people during the change process and facilitate learning of the skills that are needed to deal successfully with the new environment is essential. The basic requirement for a PLM implementation is software functionality training. Moreover, training about the basic ideas of PLM as well as in team working should be beneficial. In the event of workflow changes where also responsibilities are changed, it can make sense to train how to handle responsibility.

- Marketing: Marketing is especially important when a pilot group implementation approach is chosen. The innovative practices have to be diffused to the rest of the organization. The so-called ‘not invented here syndrome’ however makes the transformation often problematic. Therefore a marketing concept is necessary to introduce new concepts and publish successes. An informal but very efficient way of diffusing is Communities of Practice (CoP). CoP are “groups that form to share what they know and to learn from one another regarding some aspect of their work ” Key can also be used to transfer the new approaches.

- Institutionalizing of new approaches: According to the results gained from the survey and interviews, new approaches are seldom institutionalized. This, however, is viewed as an important element of a change initiative by theoreticians in order to hold the gains of an improved state and to avoid erosion effects. Therefore, this should also be beneficial for a PLM implementation, especially for the aspect of collaboration. Collaboration can for example be encouraged by regular meetings between different departments where new ideas or current problems are freely exchanged. These meetings would serve to anchor collaborative behavior in the company culture.

The achievement of business success requires many skills. Amongst these are the skill sets to assess the business environment and to capitalize on, and risk manages that environment.

The business environment includes the marketplace, yourself and your business partners, and any external factor that may positively or negatively affect the level of your business success.

Today we are going to look at three aspects of the environment; transformation, opportunities, and obstacles, and two groups of environment handling strategies; consolidation strategies, and exit strategies.

- The Amount Of Transformation Required To Reach Your Goal. Achieving any goal requires change. It is important when setting business goals to determine the amount of change required. If the change is great it may be better to break the goal down to sub-goals in order to make success more accessible. Start with the question; why hasn’t the business already attained that goal? This will help determine exactly what needs to be changed as well as the amount of change needed. It is important to determine how those changes can be accomplished in the current environment by looking at the opportunities and threats in the environment and the strengths and weaknesses within the business.

- Opportunities, Strengths, And Advantages Every environment provides opportunities to those who develop the skill of seeing them. Every business has its own strengths and its own advantages over other businesses. The wise business manager can determine the best combination of these opportunities, strengths, and advantages and then implement strategies to maximize profit at this point in the environment. Even in the toughest times, when most businesses are in trouble, there are always some businesses that are prospering. If you develop the skills for assessing opportunities, strengths, and advantages and the habit of acting on that assessment by taking appropriate goal-directed action, then your business will always be one of those that are prospering.

- Obstacles, Threats, And Limitations The environment always contains opportunities, and it also always contains obstacles. Your business always has some limitations at any particular point in time and there are always threats to your success and profitability. Since we know that these “problems” will always exist the wise business manager develops the skill of recognizing them early and develops and implements risk management strategies to guide the business through the difficulties while at the same time the business is focusing its efforts on profiting from the opportunities.

- Consolidation Strategies a business requires a change in order to grow but constant change can be destabilizing. The wise business manager determines when it is appropriate to consolidate the gains made so that those gains become a strong foundation on which to build the next campaign of positive change. A thorough understanding of the business environment can help determine the best point at which to consolidate and the best strategy to implement that consolidation.

- Exit Strategies No matter how skilled the manager is, or how well the environment is analyzed for opportunities, and threats, or how good the consolidation strategy may be, there is always the possibility that things don’t go to plan. For this reason, there is a golden rule that needs to be followed in every campaign; never enter any business campaign without a predetermined exit strategy. The best time to determine strategies for how to exit a campaign with the minimum of difficulty or loss is before the campaign starts. This is when you are calm and clear thinking. If you wait until things are going wrong and the pressure is at a peak you are far less likely to find the best solution. That was a brief introduction to capitalizing on the business environment. Now it’s up to you to put aside some time to use these five points to help you look at the current environment for your business and determine how you can capitalize on that environment to increase your business success.

Regarding the matters of managing changes, which are essential in successful business it is necessary to mention the following: fundamentally, the Managed Change Model reduces the financial and operational risks associated with a change in any organization. Productivity can be increased and expenses can be reduced by simply focusing on a critical area that often is ignored by even the most strategic executives: organizational or individual resistance to change.

In working with clients, our goals are simple. We want to help executives, managers, and key change agents:

- Become aware of the dynamics, risks, and challenges posed by organizational and individual resistance to a change of any kind;

- Accurately identify the people who will have to change and the potential reasons they might resist;

- Mitigate and quickly eliminate individual and organizational resistance to change;

- Accelerate organizational acceptance of new behaviors required by change;

- Generate appropriate plans for sustaining the change once the implementation/conversion has been completed; and

- Become knowledgeable in and practitioners of the Managed Change Model.

The net result of these goals will be clients who are armed with the critical tools to manage and own the current implementation/conversion, as well as future change projects.

Since managers cannot manage what they give little attention to, a paradox is widespread across all forms of organizational change: changes that successfully improve performance in one part of the firm often fail to translate into gains in firm-level performance. The roots of what we refer to as the “organizational improvement paradox” (see Table 1) are the feedback loops, time delays, and other change dynamics that are difficult for managers to recognize and act upon in translating local changes into broader gains.

The goal of this article is to make the dynamic complexity of organizations more accessible to managers and other change agents who seek to turn unit-level performance improvements into overall gains for the firm. We offer a conceptual tool kit, which we refer to as “linkage analysis,” to help managers conceptualize, assess, and overcome the barriers underlying the organizational improvement paradox.

It is almost an article of faith that improving the performance of one business unit is good for the business in general. Many have argued along the lines of a famous change article by R. Schaffer and H. L. Thomson, “Successful Change Programs Begin with Results,” that successful implementation in a local unit or organizational level, where it produces a local outcome, can be presumed to generate improved firm-level performance, too. All too often, though, this is not what really happens. Many otherwise successful local changes have no real payoff for the organization. The organizational improvement paradox is widespread in organizational change.

Analyses of information technology (IT) investments for many years indicate little or no impact on firm-level performance. Similarly, assessments of organizational downsizing reveal that relatively few firms have realized the cost savings or productivity increases they anticipated. In both instances, changes that had some benefit in terms of local efficiencies or cost reductions failed to achieve their expected results for the firm.

Often among the failures, a common theme has been the lack of collaborative cultural inquiry and re-designs. New work structures – such as autonomous teams – are established and people simply are expected to become empowered by these new ways in which they are working. Yet, largely due to a lack of understanding of the power of the collective human system to obstruct the progress of initiatives, many merely structural change programs have foundered. A sad result of these failures has been to reinforce fear, defensiveness, and cynicism among people at work toward organization change efforts.

In cases of successful, durable change, what are the characteristics of these programs that we can point to as important factors in the successes to date? If there are common factors in successes, what are they, and how can we learn whether these and/or other factors may be helpful for particular change agendas? And even if we can point to fortunate success stories, the question arises: what is missing in these initiatives that could help them be even more successful?

Conclusion

As the 21st Century dawns, we increasingly see a move toward the integration of methods and techniques from widespread disciplines into meta-methodologies for organizational change. In a spirit of cross-disciplinary inquiry, practitioners from fields as diverse as family therapy, martial arts, systems science, and organizational behavior are working together in teams to design new, more sophisticated approaches to change.

This monograph sketches one particular, integrative approach to organizational change. This integrative approach seeks to help organizations continually reinvent themselves by helping the people in them develop and refine new sets of interlinked skills and capabilities, ones that will help them become powerful players in the dynamics of change, minimizing the likelihood that they or their organizations will be left in the dust. The general, or contextual, model of organizational change is one featuring at least three streams of coordinated inquiry and design.

Cultural: in which all the stakeholders examine the culture and values they currently have, reinventing them, if necessary, to help the people work together effectively in new and more effective ways. Additionally, practices from fields such as family therapy, mindfulness meditation, and the martial art of Aikido are offered for enhancing individual leadership through increasing inner mastery.

References

Alexander, Karl L., Doris R. Entwisle, and Susan L. Dauber. On the Success of Failure: A Reassessment of the Effects of Retention in the Primary Grades. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Bielski, Lauren. “What Makes a Good Leader? the Go-To “Guy” with Vision and Passion Will Top the Org Chart-And Lead Change Management.” ABA Banking Journal 97.12 (2005): 21.

Burns, Rex. The Yeoman Dream and the Industrial Revolution The Yeoman Dream and the Industrial Revolution. Amherst : University of Massachusetts Press, 1976.

Cummings, Annette Merrit. “Achieve Diversity through Change Management.” Black Enterprise 2002: 105.

Dryden, Windy. Reason to Change: A Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy (Rebt) Workbook. New York: Brunner-Routledge, 2001.

Frame, J. Davidson. The New Project Management: Tools for an Age of Rapid Change, Complexity, and Other Business Realities. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2002.

Friesen, Michael E., and James A. Johnson. The Success Paradigm: Creating Organizational Effectiveness through Quality and Strategy. Westport, CT: Quorum Books, 1995.

Herman, James. “The Challenge of Managing Change.” Business Communications Review. 1996: 78.

Kay, John A. Foundations of Corporate Success: How Business Strategies Add Value. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Kelley, Karol L. Models for the Multitudes: Social Values in the American Popular Novel, 1850-1920. New York: Greenwood Press, 1987.

Lynn, Kenneth S. The Dream of Success: A Study of the Modern American Imagination. 1st ed. Boston: Little, Brown, 1955.

Makin, Peter, and Charles Cox. Changing Behaviour at Work: A Practical Guide. New York: Routledge, 2004.

Malaty, G. 2004. Mathematics Teacher Training in Finland. In: Series of International Monographs on Mathematics Teaching Worldwide. Monograph 2. Teacher Training. Budapest: Müszaki Könyvkiadó, A WoltersKluwer Company.

Pennel, J.P. and Winner R. I. Concurrent engineering: practices and prospects, IEEE Global telecommunication Conference and Exhibition. Part 1, Institute for Defense Analyses, pp. 647-655 1989.

Pettibone, Craig. “Leadership Challenges Facing Today’s Federal Managers: The FEIAA’s Recent Executive Forum Shared Best Practices in Human Capital Management, Financial Management, Competitive Sourcing, Change Management, and Leading across Generations.” The Public Manager 35.1 (2006): 64.

Rogers, Stephen M. “Access for Success.” Security Management Nov. 1997: 14.

Shaver, Kelly G., et al. “Attributions about Entrepreneurship: A Framework and Process for Analyzing Reasons for Starting a Business.” Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 26.2 (2001): 5.

Tantoush, T., Clegg, S. CADCAM integration and the practical politics of technological change. Journal of Organizational Change Management, Vol. 14 No.1, , pp. 9-27 2001.

Tsao, S. An Overview of Product Information Management Pan Pacific Conference on Information Systems. 2003.