Introduction

“Consumer behaviour is the way that consumers act or behave when looking for, buying, and using products” (Dougherty, 2007). It focuses on how consumers choose and dispose services and products. The decision making process is complex and involves many psychological processes.

Consumers must take time to recognize their needs, find possible, effective, economical, and convenient ways to solve the problems, before arriving at a buying decision (Mort, 1997). Despite the complexity of the decision-making process, consumers are faced with product decisions daily.

In fact, product decision has become so integral to consumers and producers that billions are spent daily in promotion and research to influence the decision process. Currently, consumer behaviour acts as the main guide for producers in product development. It is a costly process full of uncertainties, but so critical to ignore.

Consumer behaviour affects all sectors of the economy. The demand for all products and services is, therefore, affected by changes in consumer behaviour. As such, consumer behaviour has become an effective tool for influencing the nature of products in the market and their selling prices (Bagozzi, Canli & Priester, 2002).

This research will attempt to find out what influences students to purchase cars. Having established the influence of consumer behaviour on decision making, the research will attempt to establish the specific role of consumer behaviour in influencing students to purchase cars. It will further establish gender and age disparities, if any, in car purchasing by students.

The decision to buy a car may not rest on the students alone, but also their parents. Cases that require the support and consent of parents tend to be more complicated. This is because most parents tend to be reluctant when it comes to allowing students to own cars. The main concern for parents and students intending to own cars while still in college is affordability.

However, reliability and safety are other concerns that may cause differences. This research will attempt to establish the factors affecting the choice of cars for those students who have decided to purchase cars. All car buyers consider efficiency, reliability, affordability, and “coolness” before committing to pay. Getting all the mentioned requirements in a car could be hard (Wilson, 1995).

In fact, it is only possible to get a car fitting in all the above categories in the high-end market. Most students do not fall in this market segment. Therefore, this research will attempt to determine the overriding factor, which most students will give priority in making a purchasing decision.

Gender and age segmentation will be used in this research. Age segmentation will be considered for various reasons. “The basic logic is that people of the same age are going through similar life experiences and therefore share many common needs, experiences, symbols, and memories, which, in turn, may lead to similar consumption patterns” (Hoyer & MacInnis, 2010).

Most importantly, the research will consider consumption patterns for students from three countries United Kingdom, Spain, and Greece. Since age groups tend to have a similar consumption pattern, using age as segmentation will provide a solid foundation for comparison and analysis. The research will also consider the possible influence of gender on buying decisions.

This is because “males and females can differ in traits, attitude, and activities that can affect consumer behaviour” (Hoyer & MacInnis, 2010). The research hypothesis will be formulated from set objectives and will be carefully examined without any biasness.

It is evident that the number of students purchasing cars has grown tremendously over the last few years. The trend is wide spread, as it has been observed not only in the United Kingdom, but also in Spain and Greece. As such, marketers, car manufacturers, and institutions offering higher education, are curious to know the main motivation behind the trend, which this research attempts to unravel.

Research Objectives

General Objectives

The aim of this research is to identify and analyze the factors that influence students into purchasing a car and to investigate if there are any differences on students’ decision-making in the United Kingdom, Spain, and Greece.

Specific Objectives

This research was based on seven specific objectives.

- To examine the effects of socioeconomic status on decision making.

- To examine how cultural and cultural orientation affects consumer behaviour.

- To establish what influences priorities among different age groups, races, and gender.

- To determine the contribution of other factors in influencing decision making.

- To determine the applicability and relevance of Maslow’s pyramid of needs among students interested in purchasing cars.

- To establish the relationship between self esteem and owning a car among students.

- Determine if there has been a significant change in the number of students purchasing cars as compared to five years ago.

Hypotheses

- Many students purchase cars for status and personality identity purposes

- Extensive marketing has influenced students to buy cars

- Culture influence students buying decision

- The society has started treating it as normal for a student to purchase a car

- A majority of male students are likely to buy cars unlike females because they believe it enhances their chances of dating the best women.

- Final year students are the majority car buyers

- The government and the media have influenced students to purchase cars

- The changes in the education system are some of the factors influencing car buying among students.

- That cheaper and second hand vehicles form the bulk of vehicles bought by students.

Country selection

There have been many researches on consumer behaviour and decision making. Corporations and multinational organizations have spent and continue to invest billions of dollars annually in research aimed at identifying the main driving forces in consumer decision making. Since consumers are the backbone of any organization, this trend is unlikely to stop.

The business environment has continued to be dynamic and extremely competitive, and knowing what consumers want and the possible factors that could influence their consumption can make a difference between success and failure (Decker & Learning, 2001).

However, there are little if any research works that have explored cross border or international consumer decision making. Therefore, this research aims at finding out the possible regional differences that may influence consumer decision making, especially among students in buying cars. To get a more diversified result, the research will focus on students purchasing trend in three countries, United Kingdom, Spain, and Greece.

Literature Review

This section reviews the works done by other scholars and researchers in the area of students’ buying behaviour. It also identifies research gaps for the study. To analyze effectively the existing data and to establish the existing research gap, if any, the section is divided into sub-sections.

Since the research aims to establish the purchasing trend of students in relation to gender, socioeconomic status, culture, and priorities, the literature review will be conducted under these four sub-headings. The fact that students have become the latest target market for car manufacturers such as Toyota, Nissan, Isuzu, Porsche, Hyundai, Chevrolet, and Isuzu cannot be denied.

There are many probable forces behind the trend, ranging from desire for high social status to affordability. All consumption decisions are complex in one way or the other. The forces that affect households in making purchasing decisions also affect students.

Using traditional purchasing decision process makes it hard to find out the factors that drive students to purchase cars (Schiffman & Kanuk, 1997). Therefore, it is appropriate to explore all factors affecting students, by virtue of being students first, before considering them as consumers.

Gender role in decision making

Whether it is purchasing property, consumables, or make-up, gender plays a core role in influencing the decision making process.

This research will analyse the work of Solomon, Consumer Behaviour: Buying, Having, and Being, Englewood Cliffs (1996), Jennings & Wattam, Decision making: an integrated approach (1964), and Kirchler, Conflict and decision-making in close relationships: love, money, and daily routines (2001).

“There are different types of purchase, impulse buying, habitual purchases, and genuine purchasing decisions which have been arrived at by one person autonomously or by selected people together” (Kirchler, 2001). Kirchler further states that whichever the type of purchase; gender plays a significant role (74).

Coley, conducted a research aimed at comparing the cognitive and affective differences between men and women in the impulse buying process and found “a significant difference” (2003).

Using a sample size of 277 students, Coley found out that many processes associated with buying decisions varry in intensity between the two sexes (283). Such factors include positive buying emotion, buyers ability to manage personal mood, and irresistable urge to purchase a product.

How socioeconomic status affects decision-making

According to the American psychological association, socioeconomic status (SES) “is the social standing of an individual or group in terms of their income, education, and occupation.” Numerous researches have proven that SES affects decision making. Among the reputable and highly recognised research works include:

- Bruin, W.B., Parker, A.M., & Fischhoff, B. (2007). Individual differences in adult decision-making competence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 92, no. 5, pp. 938-956. DOI: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.938.

- Finucane, M.L., Mertz, C.K., Slovic, P. & Schmidt, E.S. (2005). Task complexity and older adults’ decision-making competence. Psychology and Aging, vol.20 no. 1, pp. 71-84. DOI: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.1.71.

- Klein, M.F. (1991) The Politics of curriculum decision-making: issues in centralizing the curriculum, Albany: State University of New York Press.

According to Finucane, Mertz, Slovic & Schmidt (2005), people in the lower SES are prone to making poor decisions. Finucane et al. claims the people in lower SES experience so many problems because they are incapable of getting many things they desire including basic needs (2005).

As such, when confronted with decisions to make, their poor background may blurr their vision or infuence their choices negatively. Educated people are more informed and are, therefore, deemed capable of making informed decisions (Klein, 1991).

Cognitive functions are also known to decline with age (Finucane et al. , 2005). As such, older individuals are prone to making poor decisions. Since this research focusses on students, the possibility of buying decisions being affected or influence by age is minimal.

Effects of culture on decision making

Kalman describes culture as, “The way we live. It is the clothes we wear and the foods we eat. Culture is how we have fun” (2010). Culture encompasses all aspects of human lives, food, language, beliefs, traditions, and values.

According to (Donnel, 2007), “People with different cultural backgrounds have different expectations, norms and values, which in turn have the potential to influence their judgements and decisions as well as their subsequent behaviour.” He further highlights the cultural differences and their possible effects on decision making by giving two examples.

European Americans, for example, are generally influenced by the positive consequences of a decision, whereas Asians appear to be more influenced by the negative consequences that may occur due to a decision or line of action. Asians are therefore more “prevention” focused, manifesting a greater tendency to compromise, seek moderation or to postpone decisions if it is possible. (Donnel, 2007)

Since this research is to be carried in three countries, United Kingdom, Spain, and Greece, there is a high possibility that cultural diversity could affect the outcome of the research.

The changes in the education system have influenced car buying among students (H1)

The increased demand for education has led to the emergence of numerous learning institutions (Smart, 2011). Unlike centuries ago when educational institutions were solely owned and run by governments, changes in the education sector, coupled with increased demand for education, has necessitated private investments in the education sector.

The emergence of private institutions has seen increased competition for students’ enrolment. The increased competition has “seen some centres amalgamate with other units” to increase operations and dominance in the industry (Smart, 2011).

The institutions have also introduced many luxurious facilities such as swimming pools and student parking to position themselves as preferred choices for students. Such moves could be considered as potential influence for students who own or are considering buying cars.

Final year students are the majority car buyers (H2)

Final year college students are liable for various financial facilities such as credit cards, and loans. Most of them are also involved in money generating activities such as part-time jobs (Eyring, 2010). The final year students are, in most cases, left with only a few units to complete college education.

Therefore, most of them choose to spend wisely the extra time by taking up jobs. Since job schedule can clash with college programme, the students may find it inconveniencing using public means to juggle between job and school. This is because public transport can be inflexible.

Worst still, some colleges are located far away from access roads, which makes the two engagements, college and job, hard to sustain. In such cases, the students may be forced to buy a car to keep the job while continuing with education. Most employers need relevant experience and quitting a job is something that most college students detest (Berger, 2012).

According to the United Kingdom’s department of higher education 2011, “These days nearly all students have some sort of a part-time job. It might be anything from working a few evenings in a supermarket or behind a bar to dog walking or babysitting. “The desire to keep a job and continue with college is, therefore, a considerable drive to students to purchase a car other than SES.

Extensive marketing has influenced students to buy cars (H3)

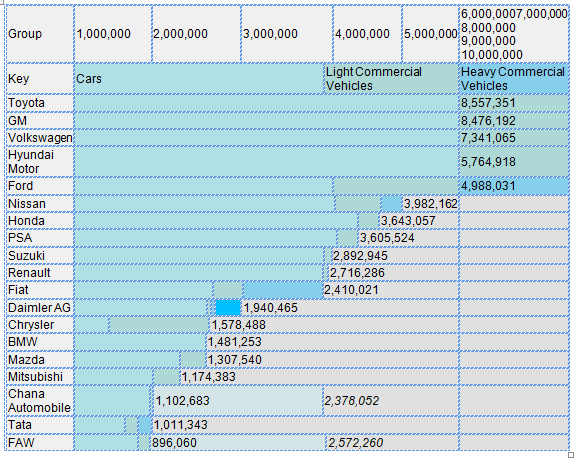

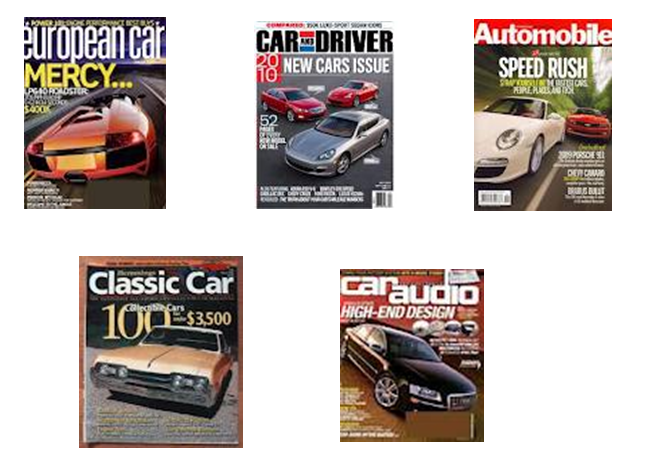

The competition in the motor industry has reached fever pitch. Dominant car manufacturers such as Toyota, GM and Hyundai, are embroiled in all types of marketing campaigns aimed at increasing sales and market share. The list of leading motor manufacturers by volume of sales by 2011 is provided in appendix 1.

As the competition in the motor industry intensifies, it is not only the quality of cars that improves, but also promotion campaigns and accessories installed in the cars. Motor manufacturers have exploited different promotional methods, online advertisements through social sites such as FaceBook and Twitter and company websites, road shows, brochures, auto magazines, and video games.

These advertisements are so visually loaded that they lure not only students, but other potential customers. Sample of auto-magazine covers that have ignited demand are attached in appendix 2. The use of celebrity endorsement has had a fair share of influence among students who idolize them.

The potentiality of student market cannot be ignored. Car manufacturers having realised this, have resorted to all ways to appeal to students’ perception and beliefs to influence them to buy cars. Advertisement that features “cool for you and your colleagues” are no surprise anymore.

It is not only the visual aspects of the advertisements that have been bent to suit the student population, but also the language used. The use of slag in advertising low-end market cars is a common phenomenon.

Many students purchase cars for status and personality identity purposes (H4)

In attempts to embrace equally in the educational institutions, the institutions have adopted guidelines and policies that ensure no student is treated in any special way. Many institutions have attempted to improve the learning environment as well as facilities for aiding the learning process to ensure maximum comfort of learners (Collins, 2011).

Despite the facilities provided in the institutions, many students still opt to buy cars and still go as a far as bringing them to school. It is believed that this is a move to make them stand out from the crowd.

This is a probable explanation especially to those students who live in the institutional facilities, but still choose to come with their cars. Since many things in the institution food, rooms, and facilities such as libraries and laboratories are shared indiscriminately, owning a personal car sets one special or in a class of their own.

Methodology

The three countries under study have a large number of students’ population in High schools, tertiary colleges, and universities. As such, selecting a representative sample is a complicated task. However, the consumption trends show concentrated purchase of cars in colleges and universities.

As such, emphasis will be put on these specific groups. Considering the existence of only a few researches carried out to establish the factors that influence students to buy cars, a qualitative approach will be adopted since it is the best option for such a research.

The cost and time involved in carrying out a primary research is extremely high. As such, the research will rely on other concluded works to provided additional information for secondary data. According to (Jackson, 2012), secondary data are data already collected by some other researchers for different purposes.

These data are essential as they form the foundation for building new research and correcting earlier inaccuracies. No work of research can collect data for all the variables needed to complete the research without using already existing data. Such a research would be too expensive and would take a very long time.

However, for secondary data to be of help, they must be readily available, accurate, sufficient, and relevant (Stewart, 1984). The data collected from secondary sources, in this case, will supply both qualitative and quantitative data.

The data collected from secondary sources will be used for analysis and interpretation of primary data. As such, no secondary source will be used as a basis for further research. Instead, they will provide crucial information to bridge research gaps.

Most data used in the research will be collected from primary sources. “Primary data refers to information collected for the first time specifically for a research study” (Kurtz, 2012). Data collected from primary sources is unique and suits the purpose for which it is collected.

There are many methods of primary data collection. The main methods include critical incidents analysis, interviews, diaries, observation, case studies, portfolios, focus group interviews, and questionnaires (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2003).

The selection of appropriate data collection method requires the consideration of many factors such as cost, efficiency, and time available. In this case, focus groups, questionnaires, observation, and interviews will be used. The choice of questionnaires is prompted by its numerous advantages.

Questionnaires are cheap to administer, have the ability to cover a wide geographical area, can be emailed hence no need for administrators, and ensures respondents anonymity.

Focus groups, on the other hand, will be used to collect qualitative data. “A focus group could be defined as a group of interacting individuals having some common interest or characteristics, brought together by a moderator, who uses the group and its interaction as a way to gain information about a specific or focused issue” (Marczak & Sewell, 2011).

Focus groups will be used in collecting primary research because they provide the opportunity for recording not only individuals reactions, but also their attitude in relation to car ownership by students. Additionally, a focus group allows for interratction and broader discussion of the topic at hand (Barbour, 2007).

For the opurposes of this study, three focus groups will be formed consisting of 10 individuals, five from each gender. The age of focus group members will be 18-25 years. There will be one focus group in each country, United Kingdom, Spain, and Greece. They focus groups will meet for approxiamtely one and a half hours to avoid lose of interest and fatique. This will also help reduce the chances of deviation.

Since one of the objectives of this research is to establish the validity of the cliam that the majority of students who buy or consider buying cars are final year students, members of the focus group will not be randomly chosen, but will be selected from the various years of study, first, second, third, and final year students.

Gender is also one of the varriables in the research and as such, the composition of the focus gropups will take care of gender balance. In brief, each focus group will comprise of males and females in their first to final year study in the selected institutions.

Since culture and cultural orientation influences decision making, the focus groups will be enriched by selecting people of various races and cultures, and the environment in the focus groups regulated to favour divergent opinions and perceptions.

The efficiency and accuracy of data received from the focus groups will be reinforced further by covering a few questions, five to seven questions. Since the focus group participants will not be paid, provision of a comfortable environment is essential.

Comfortable chairs and quality refreshments will also be provided to enhance corporation and active participation. Further, the focus group meetings will be held in the respective institutions where the participants take their classes or in a close proximity to the institutions to curb inconveniencies arising from long travelling.

Probing questions have been developed to help the focus groups in the discussion process. A copy of the questions is provided in appendix 3.

The inefficiencies of focus groups as a primary source of data cannot be ignored (Jenkins & Harrison, 1990). Focus groups give a researcher no control over data received, some of which can be quite irrelevant. The data from focus groups is often jumbled, which makes the analysis process quite complicated.

Lastly, establishing the accuracy of data received from focus groups is an insurmountable task. These inefficiencies can hinder accurate results and, therefore, many checks have been put in place. For, instance, the data collected from focus groups will be compared with those collected from interviews and observations before any conclusion is arrived at.

Interviews will also form part of primary data collection methods. “An interview is a conversation, usually between two people. But it is a conversation where one person A the interviewer, is seeking responses for a particular purpose from the other person: the interviewee” (Gillham, 2003).

The choice of interviews as a source of primary data has been prompted by the fact that it gives the interviewer an opportunity to clarify questions and concepts that the interviewee might not be familiar with, something impossible with questionnaires. Its flexibility is also an added advantage, since it allows the interviewees to respond in any way they deem appropriate provided the response can be understood and captured.

When focus groups fail to highlight individuals’ attitude, perceptions, and beliefs, interviews provide the interviewer with the opportunity to capture these important variable, which significant influence purchase decision. Car sellers and manufacturers will be interviewed to establish the purchasing trends of students. If possible, data for sales to students for a period of the past five years will be collected for analysis.

Students will also be interviewed to find out if they own cars, or are considering owning one. Considering the low confidentiality of the research topic, both structured and unstructured interviews will be used. Structured interviews will be used because they save time and present same questions to interviewees leading to consistent and relevant data output.

Unstructured interviews, on the other hand, will be adopted due to their flexibility, their ability to provide room for the interviewees to express their emotions, attitude, and perceptions, which are core to this research. The structured interview questions are attached in appendix 4.

Common errors associated with interviewing such as poor responses resulting from poorly framed questions, probing errors, which may occur due to provision of insufficient time to the interviewee for answering interview questions, and lack of motivation and concentration of the interviewees, have been put on check to eliminate any possible errors in the findings or to reduce error margin significantly.

Due to cost reduction efforts, most interviews will be conducted through telephone calls. After identifying the correspondents, scheduled telephone interviews will be conducted at the convenience of the interviewees. Conducting telephone interviews comes with a host of challenges (Marcus, 2011).

Since it involves communicating to people we do not see face to face, it is impossible to tell how committed, attentive, and willing they are to be interviewed. This is because it lacks facial clues, which are crucial in determining the level of commitment of an interviewee. The curiosity involved when dealing with telephone interviews further complicates its application.

Many people find it hard responding to questions, especially when private information is involved, from strangers. Since the research will require the financial status of the students who have purchased cars, it will be important to emphasize the confidentiality of the information provided to boost the confidence of the interviewees.

As such, the introduction to interviewees will be extensive and professional. The purpose of the research will also be stated to eliminate suspicions, which could lead to lack of cooperation or giving of false information. All interviews will be recorded for quality and data analysis purposes.

The last primary data collection method to be used in the study is observation. “Observational data collection methods are techniques for gathering qualitative data by watching the behaviour of individuals without direct questioning” (Hartog & Staveren, 2006). It entails “the systematic noting and recording of events, behaviours, and artefacts (objects) in the social setting chosen for study” (Page, 2000).

Page further claims, “Observation is a fundamental and highly important method in all qualitative inquiry” (2000). The observation process will be structured to enable easy coding and analysis. As such, all cars entering the selected institutions will be recorded. Since all vehicles entering institutions are not only for students, the ones that belong to students will be selected from student parking.

Fine details such as vehicle models and the sex of the drivers will be noted. This is because the research aims to establish gender disparity in car ownership among students. For easy analysis, the observation process will be recorded by the use of a video recorder. Note taking will also run concurrently to ensure that no fine details are missed out.

Because observation will not provided some important information such as the age of the students with cars, which is a critical requirement for this research, approximation will be used. However, the most important information to be collected form observation will be the number of cars owned by students and their models.

In this way, observation will give a direct and concrete evidence of car ownership by students and will help to validate the other data gathered through interviews and focus groups. In brief, the data to be collected through observation will be categorized into:

- The car models owned by students

- The sexes of the car owners

- Year of study of the students owning cars

The use of multiple data collection methods, interviews, focus groups, and observation, was meant to eliminate the occurrence of “inappropriate uncertainty” (Sheḳedi, 2005).

The idea is also supported by Wholey, Hatry & Newcomer (2010) who cliam it is appropriate to “…use multiple data collection strategies to verify or refute findings …Here the solution is to analyze all available data using multiple techniques and addressing rival hypotheses” (179).

After the data collection exercise, the data is then expected to be refined and thoroughly analyzed for any deviant or misleading information. Any information that will show a significant deviation from the others will be ignored. The selected data will then be analyzed using packages such as computer assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS).

The variables expected to be used will include number of cars owned by students in the three selected Universities in the United Kingdom (Oxford), Spain (Universitat de Barcelona), and Greece (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki), the ratio of males to females owning cars, and the specific car models.

Results and Discussion

Introduction

This chapter presents the results from the three primary sources of data collection that were employed in the research. It further discusses findings from the in-depth interviews conducted; structured observations made, and focus group reactions.

Focus Groups

The three focus groups formed to collect relevant data for analysis gave different but close results. The main objective of the focus groups is to find out if the participants own cars or are considering buying one. The probing questions designed to guide the focus groups were responded to in varied ways.

For instance, when asked, “Do you own a personal car?” There were two definite answers, yes or no. Still, others who did not own cars indicated that they were considering it. Other interesting findings emerged from the responses.

Male students who owned cars, did not only stop at accepted the ownership, but also went ahead to mention the car models. “Yes, a 2012 Toyota Camry Hybrid.” “Yes, a Hyundai Sonata.” “Yes, a refined, comfortable, and extremely quiet Toyota Highlander.”

It was even more interesting as those students who owned sports cars and other expensive brands showered their cars with praises and even at times quoted their purchase prices. Others went ahead to give fine performance details of their cars. The groups almost turned into motor shows, but this did not affect the quality of data recorded, instead, it enriched the data. Some of the recorded reactions are discussed below.

One group member, an evidently proud owner of a Ford Mustang sports car said, “It is not only legendary, but also has low fuel consumption and a persuasive V8 power. It combines versatility and utility making it the best choice for any student. ”

Another member who owned “The Infiniti G” praised it in equal measure, if not in a higher degree. “ The car has the best interior design in the world that provides unrivalled comfort. It also has a blistering acceleration.” One oxford student owning a 2012 Mazda MX-5 Miata described it as “an epitome of comfort that sets the standard for practicality and fuel economy.”

There were also females who owned cars. However, it seemed most of them were not informed of their cars specifications or were simply not interested in talking about them. This is because most females who had cars hardly mentioned their models. Even after asking the cars’ models and performance specifications, only 40% of the females could give detailed information.

All males liked the idea of owning a car. The males who did not own cars were considering buying or would be glad to own a car, but face financial challenges. On the other hand, only 60% of females liked the idea of owning a car. They claimed owning a car in college “may intimidate potential dates.”

They further claimed men “are scared of women they consider dominant, classy, and independent,” attributes associated with owning a personal car in college. A considerable 10% said they would rather support their boyfriends to buy a car than own it themselves. It is, however, interesting that even the females who were not for owning cars in college, were not against fellow females owning them.

The UK female students who were in the Oxford focus group, seemed to have a different opinion from their Greece and Spain counterparts. They strongly believed owning a car is essential for all students. The ones, who did not own one yet, strongly believed they would be happier and more comfortable if they owned one.

Concerning the claim that students buy cars for prestige and social status, a considerable number agreed. Male students in Spain and Greece indicated that owning a car attracts considerable respect from the students’ fraternity and even college tutors. A whopping 60% said car ownership attracted females and increases one’s chances of dating high-class females. One male claimed, “Females want successful males.

Owning a car is a symbol of success.” They also claimed owning a car increased morale and self-confidence. Students in the United Kingdom share this position. However, they tend to view car ownership in a completely different perspective. They consider it as a means of improving educational horizon like attending off-site classes and going for internships.

Female participants overwhelmingly agreed that they would consider men who owned cars more successful than the ones who did not, even if; their guardians buy the cars. One claimed, “It is hectic dating a guy who has no car because going for parties is hard without a car.”

Males, on the other side, felt immense pressure to measure up to the demands and expectations of their female counterparts, which forces them to buy cars if they are not to be treated as second in social ranking.

Regarding the influence of government and educational institution’s on student’s car buying decisions, most students felt the two factors did not make any significant contribution. In Spain, for instance, the government has provided incentives for students who want to purchase cars (Vaughan, 2012).

Many people believe this move has elicited interest among students to buy cars, pushing even those who would otherwise not be interested in purchasing cars to consider doing so. Educational institutions have also contributed in influencing car buying among students.

According to one focus group member, “institutions have continued to create conducive environment for car ownership that have enticed students to buy cars. Security for students’ cars while in college premises has been heightened. Parking spaces are not only provided, but are also well maintained.

Despite these incentives, many students feel the government and the education institutions are simply following the wishes of the students, as consumers.

In terms of priorities, still the focus groups had varied concerns. Despite inability to fulfil sufficiently other basic needs, some students chose to buy cars. The consumption of cars by students is in contravention of the theory of the hierarchy of needs developed by Abraham Maslow.

According to the theory, a person can only seek higher needs after satisfying lower needs (Goble, 2004). In this case, some students who have bought cars accept that they still face every day challenges such as affording descent meals.

Purchasing a car is for esteem needs as stated, but it leaves a lot to desire as to why students would buy a car when they still have a lot to achieve in terms of basic needs, safety needs, and social needs.

Interviews

Three car dealers were interviewed to establish the purchasing trends of students. Since students purchase various types of cars Isuzu, Mitsubishi, Toyota, Mercedes, Nissan and many more, choosing a suitable dealer was a complicated task.

To get a more representative data, dealers who stock various car models were selected over those that stock specific brands. The selected dealers are Wheatley Car Centre in Wheatley Oxford, Mastertrac S.A, Barcelona, and Spanos in Athens.

From the interview with the managing directors of Wheatley Car Centre, it was apparent that the company treasured students as a potential market for new and used cars. This is because the company had a variety of affordable cars and incentives such as discounts for every sale and recommendations.

Appendix 5 provides the list of cars in the student’s section of the store at the time of visit. According to the manager, students prefer affordable cars with low fuel consumption, which prompted them to open a section with such cars. The manager also confirmed that their student customers are both female and males. However, he said there is a disparity in sales in terms of gender. Out of every nine customers, only one is female.

The interview with Mastertrac’s sales representatives revealed closely related findings. The numbers of students who purchase cars have been growing steadily. Despite the growth, only a few female students purchase cars. Despite massive advertisements and incentives, the response from the female students has been low.

The interview also revealed that the few females who went to purchase cars seemed to have little or no information on the type of cars they wanted. They preferred using price to guide them in making a buying decision. One sales man said, “Ladies simply want what they can afford, regardless of how it performs.”

Another one said, “Ladies go for how a car looks and consider its affordability while completely ignoring its performance.” Unless the females come with someone to advice them and help them choose a car, they are likely to buy a completely different car from what they had in plan, provided the sales representative does a little persuasion.

The Spanos’s interview also gave many similar revelations. The number of students purchasing cars has increased. However, the store did not have data showing gender difference in sales. They also indicated that the students were not limited to low cost cars only, as some bough expensive sports cars. Additionally, other students requested pimping and customization of their cars.

The three interviews gave very conclusive findings. Most importantly, the information received did not greatly deviate from the information from the focus groups.

Observation

The institutions under observation had parking lots for students. In fact, the students’ parking lots were more spacious than staff’s parking lot. This is a clear indication that the number of students owning cars is higher than the number of support and teaching staffs owning cars. Many vehicles owned by students, assuming all the cars parked at the students’ parking lot belonged to students, are quite affordable.

In the UK and Greece, however, there were mixes of low-end and high-class cars owned by students. There was also an interesting observation made in Spain. Over 80% of males who owned cars drove into the institutions with their car windows down. This was perhaps meant to draw attention and could be used to deduce that they are proud of owning the cars. Those who owned expensive sports cars were the worst victims in this category.

Over 90% of the females observed driving into the institutions, on the other hand, had their windows up. In fact, it was almost obvious that females drove any car that was approaching with windows down. It was also observed that the few females who owned cars, owned expensive ones.

Most male students also had their cars pimped to suit their taste. Their cars had loud music systems, stickers, and mixed colours or in some cases abstract images. This is contrary to the belief that women like fancy things because most cars owned by female students were plain.

Another important observation made in the sales stores was that students frequently came to window shop for cars. Male students were the majority of window shoppers. Those who had purchased cars came to check on new arrivals, even if they didn’t intend to make new a purchase. Females, on the other hand, visited the stores only when they intended to buy or escorted friends to buy cars.

Analysis of Findings

Most findings from the focus groups, interviews, and observations were in support of the hypotheses of the research. Some of the findings, however, were in contradiction of the hypotheses. H1 predicted that students buy cars because of favourable and luring environment created by educational institutions such as parking lots and security. Students in the focus groups thought contrarily.

They said the created environment by the institutions was simply due to increased car ownership by students and the desire by the institutions to create sanity in parking. This was concurrent with interview finding, which indicated that other factors other than socioeconomic status, culture, and priorities played on 5% role in influencing students’ decision to buy cars.

As expected, the majority of students buying cars are final year students. Members of focus groups who did not own cars said they would only consider buying when they are in their final year of study. Even the students who did not approve owning cars while still staying said it was acceptable for final years to own one.H3 predicted that extensive marketing plays a significant role in influencing students to buy cars.

Focus group members from all the three countries researched noted that advertisement played a role in convincing them that they needed cars. In fact, even members who had not purchased cars said they are under constant from the advertisements, some of which are “pinned in toilets and bathrooms.”

The fact that most students buy cars to gain recognition and social standing was overwhelmingly confirmed. Interview results showed that 60% of students felt they were treated better than others because they owned cars. However, it was the results from the focus groups that were more interesting.

Male students who owned cars said it places them in “a better position to date the best women” in campus. While the female students said they were unlikely to be influenced to date a male for owning a car, they admitted that they viewed the males who had cars as serious in life and of high social standing. Observations also confirmed this hypothesis overwhelmingly.

It was observed in Spain that over 80% of males who owned cars drove into the institutions with their car windows down. However, only 10% of females had their windows down. This is an indication that the students who owned the cars felt special and were proud of owning the cars.

Further, it was observed in the United Kingdom that students who owned cars pimped them and often came in campus playing loud music. This is perhaps another confirmation that the car owners seek attention from other students.

Cultural and government influence on car buying was insignificant. Many students in focus groups were not aware of any government incentives aimed at stimulating students demand for cars.

The fact that 40% of those in focus groups in Spain said they are unaware of government incentives despites vigorous campaigns confirmed the little influence the policies have on students buying behaviour. The fact that the research was carried out in three countries with diverse cultures and still had consistent results is a clear indication that culture played an insignificant role too.

Conclusion

The findings from this research have shown that the number of students buying cars has increased, and that the trend is likely to continue. According to the research, the factors influencing students to buy cars range from desire for high social status, recognition, extensive marketing by motor manufacturers, and societal expectations, to improving educational horizon like attending off-site classes and going for internships.

Whichever the reason for buying a car, it is time for motor vehicle manufacturers to realise that the student fraternity has become a significant market for motor cars.

To succeed in selling to students, the following methods have been identified as effective. Investing in extensive marketing using social media, brochures, websites, and posters pinned in learning institutions have been identified to have significant influence on students’ buying decision.

The fact that social standing is a major driving force for students buying cars, the advertisements should be crafted to portray high social standing of owners.

Finally, it is evident that people of 18-25 years are driven more by esteem needs and will do everything possible to satisfy these needs even when their basic, safety, and social needs are threatened. It explains why many students rush to buy cars when they can hardly afford decent meals.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Leading motor vehicle manufacturing companies by volume 2010

Total motor vehicle production

Appendix 2: Sample auto-magazine covers

Ebscomags cited in Vaughan, 2012, p.14

Appendix 3: Discussion Guide for the Three Focus Groups

General guidelines

- Achieving the full participation of the focus group members is essential. As such, it is important to welcome the members and make them feel comfortable and treasured.

- After the introduction, it will be important to communicate to all group members the aims and objectives of the focus groups.

- To avoid the reluctance of members divulging confidential information for fear of being exposed, confidentiality of collected information will be affirmed.

- The interaction process will be recorded for analysis.

- The discussion is to be as free flowing as possible. Therefore, the set probe questions must not be followed in that sequence, but in any order.

Appendix 4: Questionnaire Design

Cover letter

Dear sir/madam,

I am a final year marketing student. As a course requirement, I am supposed to carry out a marketing research in any area of interest. As such, I have decided to research on “why students buy cars?” As a student, I have selected you to assist in the research process by filling in the questionnaire.

Please answer the questions as honestly and precisely as you can. I would also like to assure you that any information provided here in will be handled confidentially, and will not be used for any other purpose not specified without your permission. After completing the questionnaire, please send it to me using the “reply” option in this email. I expect the completed questionnaire by 20/06/2012.

Instructions

- Answer all the questions

- Tick where appropriate

Questions

- Do you own a car?

- If yes, how did you acquire the car?

- If you bought it, what inspired you to do so?

- Do you feel treated better because you drive?

- As the car helped achieve the intended purpose?

- What is your monthly average income any?

- Does your income influence your purchasing significantly?

Appendix 5: List of Cars at Wheatley Car Centre

References

Bagozzi, P, Canli, Z & Priester, R 2002, The social psychology of consumer behaviour, Open University Press, Buckingham, England.

Barbour, R 2007, Doing focus groups, SAGE, London.

Berger, L 2012, All work, no pay: finding an internship, building your resume, making connections, and gaining job experience, Ten Speed Press, Berkeley, Calif.

Bruin, B, Parker, M & Fischhoff, B 2007, ‘Individual differences in adult decision-making competence’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 92 no. 5, pp. 938-956.

Coley, A 2003, ‘Gender differences in cognitive and affective impulse buying’, Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, vol. 7 no. 3, pp. 282 – 295.

Collins, J 2011, The Greenwood dictionary of education, 2nd edn, Greenwood, Santa Barbara, Calif.

Decker, D & Learning, Inc. 2001, Customer satisfaction, 1st edn, Crisp Learning, Menlo Park, CA.

Donnel, B 2007, The Effects of Culture on Decision Making and Judgment. Web.

Dougherty, D 2007, Consumer behaviour, Pearson Education South Africa, Cape Town.

Eyring, J 2010, Major decisions: taking charge of your college education, Deseret Book Co., Salt Lake City, Utah.

Finucane, L, Mertz, C, Slovic, P & Schmidt, S. 2005, ‘Task complexity and older adults’ decision-making competence’, Psychology and Aging, vol 20, no. 1, pp. 71-84.

Gillham, B 2003, The research interview, 2nd edn, Continuum, London.

Goble, G 2004, The Third Force: The Psychology of Abraham Maslow, Maurice Bassett, New York, NY.

Hartog, A & Staveren, W 2006, Food habits and consumption in developing countries: manual for social surveys, Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen.

Hoyer, D & MacInnis, J 2010, Consumer behavior, 5th edn, South-Western Cengage Learning, Australia.

Jackson, S 2012, Research methods and statistics: a critical thinking approach, Wardsworth Cengage Learning, Belmont, CA.

Jenkins, M & Harrison, S 1990, ‘Focus Groups’, A Discussion British Food Journal, vol. 92 no. 9, pp. 33-37.

Jennings, D & Wattam, S 1994, Decision making: an integrated approach, Pitman, London.

Kalman, B 2010, My Culture, Crabtree Publishing Company, St. Catharines.

Kirchler, E 2001, Conflict and decision-making in close relationships: love, money, and daily routines, Psychology Press, Hove, England.

Klein, M 1991, The Politics of curriculum decision-making: issues in centralizing the curriculum, State University of New York Press, Albany.

Marcus, A 2011, Design, User Experience, and Usability. Theory, Methods, Tools and Practice First International Conference, DUXU 2011, Held as Part of HCI International 2011, Orlando, FL, USA, July 9-14, 2011, Proceedings, Part II, Springer-Verlag GmbH Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Marczak, M & Sewel, M 2011, Focus Groups, London, Continuum.

Mort, T 1997, Systematic selling: how to influence the buying decision process, AMACOM, New York, NY.

Page, S 2000, ‘Community research: The lost art of unobtrusive methods.’, Journal of Applied Social Psychology, vol 30, no. 10, p. 2126–2136.

Saunders, M, Lewis, P & Thornhill, A 2003, Research methods for business students, 3rd edn, Prentice Hall, Harlow, England.

Schiffman, G & Kanuk, L 1997, Consumer Behavior, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River New Jersey.

Sheḳedi, A 2005, Multiple Case Narrative: A Qualitative Approach to Studying Multiple Populations, John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam.

Smart, J 2011, Higher education handbook of theory and research, Springer, Dordrecht.

Solomon, M 1996, Consumer Behavior: Buying, Having, and Being, Englewood Cliffs, Prentice Hall, New Jersey, NJ.

Stewart, D 1984, Secondary research: information sources and methods, Sage Publications, Beverly Hills.

United Kingdom’s Department of Higher Education 2011, Working while studying, Government printer, London.

Vaughan, A 2012, ‘Government launches £5,000 car grant scheme’, AutoShow, vol 67, no. 3, pp. 13-17.

Wholey, S, Hatry, P & Newcomer, E 2010, Handbook of practical program evaluation, 3rd edn, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Wilson, Q 1995, The good car guide, BBC Books, London.