Introduction

Research has highlighted that a positive correlation exists between tobacco smoking and cancer (Beral, Gaitskell, Hermon, Moser, Reeves and Peto 948; Doll and Hill 740). According to, Huncharek, Haddock, Reid and Bruce, tobacco smoking is a major cause of cancer (694). In this research study, data on tobacco smoking and cancer prevalence in the United States was used to determine whether cancer in the United States is related to tobacco smoking tobacco. It was hypothesized that tobacco smoking in the United States is correlated with cancer.

Methodology

The research relied on data obtained from the United States National Cancer Institute data. The databank includes data collected through a questionnaire from 3,185 respondents. Only two variables, ‘have you ever been diagnosed as having cancer’ and ‘have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life’ of the cycle 3 dataset (updated in 2014) were of interest in this research study. Correlation and regression analysis was performed to determine whether tobacco smoking and cancer are related. The significance of the results was based on an alpha level of significance of 0.01. The analytical software, SPSS, was used to perform the analysis.

Results and Analysis

Table 1 shows that all the 3185 respondents provided feedback and there was not missing data points. In other words, the sample size (N) was 3185.

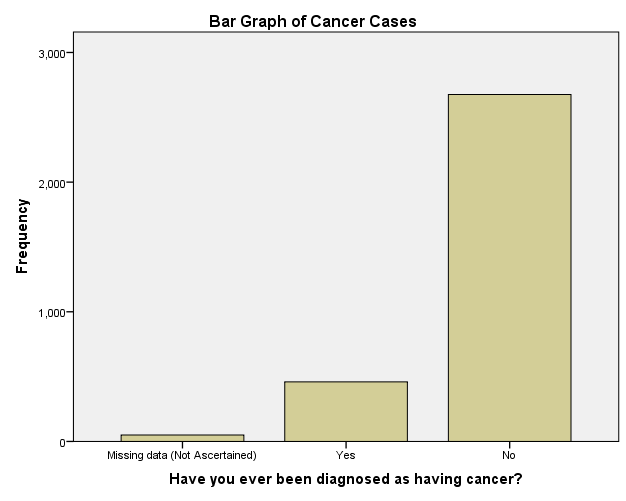

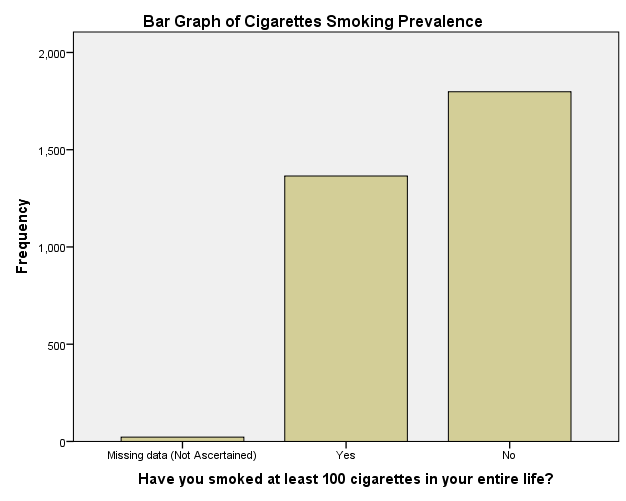

As shown in table 2, only about 14.4% (or 459 of the people sampled) have ever been diagnosed with cancer while 84% have never had cancer. Approximately 42.9% (which is 1365 of the persons sampled) have smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their entire life. The rest (about 56.5%) had not smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their entire life (table 3). These statistics are shown graphically in figure 1 and 2 below

Correlation and Regression

The results of the correlation and regression analyses are summarized in table 4 to 6. The correlation coefficient (r) of 0.275 (table 4) suggests existence of a low positive correlation or relationship between smoking and cancer.

Significance Testing

The null hypothesis was that no relationship exists between smoking and cancer while the alternative hypothesis was that a relationship exists between smoking and cancer. Based on an alpha level of significance of 0.01, the null hypothesis was rejected (P < 0.01). This means that indeed cancer is correlated to smoking.

The relationship between cancer and smoking can be represented by the following regression model: cancer = 1.112 + 0.382 smoking. Theoretically, the model implies that every case of smoking 100 cigarettes contributes to approximately 0.382 cases of cancer. As shown in table 6, the variables and the constant are significance (P<0.01).

Discussion and Conclusion

It would be expected that the correlation between tobacco smoking and cancer cases would be high (Doll and Hill 739). However, a low correlation between tobacco smoking and cancer was reported. The low correlation can be explained by two factors: the high threshold of qualifying a participant as a smoker and exclusion of other factors that are correlated with cancer.

The regression model obtained, cancer = 1.112 + 0.382 smoking, imply that every case of smoking 100 cigarettes contributes to about 0.382 cases of cancer. The results of the significance testing show that the regression model is significant, including the factor (independent variable) and the constant of the model. Therefore, tobacco smoking is positively related to cancer cases in the United States.

Works Cited

Beral, V, Gaitskell, K, Hermon, C, Moser, K, Reeves, G, and Peto, R. “Ovarian cancer and smoking: individual participant meta-analysis including 28,114 women with ovarian cancer from 51 epidemiological studies.” The Lancet Oncology. 13.9 (2012): 946-56. Print.

Doll, Richard and Hill. Bradford A. “Smoking and Carcinoma of the Lung.” British Medical Journal. 2.4682 (1950): 739–748. Print.

Huncharek, Michael, Haddock, K. Sue, Reid, Rodney and Kupelnick, Bruce. “Smoking as a Risk Factor for Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of 24 Prospective Cohort Studies.” American Journal of Public Health. 100.4 (2010): 693–701. Print.

United States National Cancer Institute. Public Use Dataset. n.d. Web.