- Abstract

- Introduction

- Data collection

- Advantages that loyalty cards offer to consumers

- How the advent of loyalty cards has changed consumer behavior

- Theoretical models of business development

- Consumer-focused products that companies are offering

- Data protection issues that could arise from the use of these cards

- Conclusion – Whether loyalty cards are a worthwhile venture

- References

Abstract

The paper first starts with a description of the data collection method, which is the use of secondary data. Thereafter, the research discusses the advantages that loyalty cards offer consumers such as point accumulation, having a sense of belonging, enjoying hidden perks, experiencing a better relationship with one’s retailer, and expediency of payment. Subsequently, the paper summarized how loyalty cards have altered consumer behavior. Effects of these schemes include greater customer scrutiny, greater purchases, concerns over privacy, and better customer relationship management. After an analysis of the effects, the report focused on business development models that apply to the scenario. It was found that the customer purchase funnel and game theory can assist in the development of better loyalty schemes.

Thereafter, the research looks at alternative customer-focused products that companies are offering and they included mobile loyalty programs, use of rewards in other companies, fixed rebates, product delivery, discounts, vouchers, coupons, and point of sale technology. Data protection issues were also examined in the report. It was found that exposure to consumer information to third parties can put clients in danger. The second last section of the report focused on the shortcomings of loyalty cards to consumers and they included gradual price increases, a phenomenon of exclusivity, and disincentives for consumers. Lastly, the researchers analyzed the effects of loyalty cards on retailers. It was found that they increase loyalty or purchase sizes only in developing markets. Companies in saturated markets rarely enjoy substantial changes in revenue acquisition and instead heighten their expenditures. In conclusion, the research found that loyalty cards are more beneficial to consumers rather than to retailers.

Introduction

Consumers are getting more demanding about the kind of services that they expect from retailers. Many of them are well informed about prices, manufacturing practices of the concerned companies, and the lifestyle options that different products offer them. Consequently, it is not surprising that large-scale retailers are looking for new ways of meeting these increasing demands by enhancing loyalty among their customers. This is the reason why loyalty cards have become such a visible phenomenon in the retail chain sector.

Data collection

In the research, data was collected from secondary sources. The information was taken and used for different purposes from the intended ones. For instance, theories on consumer purchasing behavior were used in order to create a model for successful loyalty programs. Alternatively, articles on consumer behavior were used in order to deduce the effect of loyalty programs on consumer behavior. Other articles that generally focused on loyalty programs were interpreted on the basis of the subtopics on the question. Since the research is descriptive in nature, then a quantitative analysis of the secondary sources was not done. Examples of these sources included books, journals, newspapers, market reports, conference papers, the internet, and other research reports.

Advantages that loyalty cards offer to consumers

The main factor that attracts buyers to loyalty cards is the fact that they will be getting a reward for simply bringing business to that retailer. Usually, these may come in the form of cash, purchases of goods, or other programs such as exotic holidays. They often gather points for every amount purchased and this can be redeemed for cash or certain goods found in the store. Therefore, one can only purchase something that is worth the amount in their loyalty cards. The more they buy from that store, the more the points they accumulate and the more purchases or returns they can get. One may get rewards on all their purchases, and in other instances, this may be done for the preferred brands. Some points can even be used outside the confines of the loyalty card retailer if the store has collaborated with other businesses. In addition, some retail stores even offer bonus points during special times. One can earn more points on such days than one would have if one shopped on a separate day. Customers appreciate the fact that they are getting additional value for something that they would normally do for free. The feeling of winning something causes so many individuals to remain in loyalty card programs (Uncles 1996).

Buyers also use loyalty cards in order to belong or have something to aspire to. If a company offers an exclusive status to the most loyal clients, then buyers will want to belong to that category for prestigious purposes. In fact, this component is more appealing to certain consumers than mere cash-back offers. It gives them something to look forward to in the future. This sense of participating in something meaningful is an important emotional advantage that buyers enjoy when they own loyalty cards.

Consumers use loyalty cards for the hidden or additional comforts that come with the program. Some sellers may provide nonproduct related perks to buyers who own these cards. For instance, this can occur in the form of better parking or faster payment processing. Firms may create express counters for particular loyal customers and this saves them plenty of time during the purchasing process. Others may stick to a certain loyalty program in order to enjoy valet parking or free parking. In fact, some facilities even offer reserved parking to a certain breed of their loyal clientele. Since convenience and comfort are important factors in determining customer satisfaction, then one might conclude that loyalty cards boost customer satisfaction. Numerous retail chains do offer their loyalty program holders more than the accumulated points as rewards. They sometimes have a special membership for those clients. They also give then discounts and bonuses. This opens up more channels for saving money.

Loyalty cards offer certain unrivaled, long-term benefits to clients. A loyalty program often allows the concerned retailer to collect information about consumers. The retailer can then use the information in order to run his store in a more efficient way. This means that the products and services obtained by the consumer will be relevant and he will enjoy a better purchasing experience in the long run. Numerous consumers engage in shopping for the experience. If a retailer can offer them excellent services thanks to data collected from loyalty cards, then chances are that the consumer will keep coming back. Many retailers realize that there are tremendous opportunities to differentiate themselves from their competition through loyalty programs (Peppers & Rogers 2004). Consequently, this has brought more innovations to the retail sector. However, such results can only take place when the retailer takes the time to analyze consumer trends.

Individuals who own loyalty cards have the advantage of enjoying a personal relationship with their retailers. These buyers can enjoy the feeling that they are the preferred customers in their chosen retailer’s store. Their retailers often communicate with them from time to time concerning certain goods or brands. Sellers may use emails or social networks in order to inform clients about these new products. They may even offer those clients previews of certain commodities. Usually, these previews are rarely accorded to the most exclusive clientele.

Loyalty cards increase the expediency of payment by introducing another currency. If a buyer does not have access to conventional payment methods at the time of purchase, he or she may still use his or her loyalty card points to complete the payment. Alternatively, if the buyer is carrying less money than is needed to make a transaction, then he can use the accumulated points instead of returning some of the products. This means that retail store transactions can now be done quickly and effortlessly.

How the advent of loyalty cards has changed consumer behavior

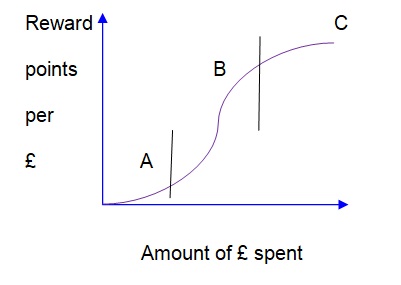

It is clear that loyalty cards have become a common feature in most retail chains. Firms have responded to their competitor’s initiatives by imitating their loyalty programs. As a result, these methods are nothing new. Furthermore, if the reward schemes are complex, then customers are unlikely to respond to them positively. Loyalty cards have arguably led to better service provision by retailers owing to service providers’ need to maintain their interest. Loyalty card programs have become more innovative, or are being used for less obvious reasons such as data collection. To differentiate the various loyalty programs, a customer must know and analyze the incentives, benefits, or advantages that a specific retailer will offer over others. In this regard, consumer behavior has changed dramatically because now buyers are more aware. They are likely to respond to loyalty programs only when it becomes clear to them that they will really get value for their money. For instance, one must think about the ratio of the product purchase to the amount of money that needs to be accumulated in order to have sufficient points. Such scenarios are quite common among highly saturated markets (Reinartz & Kumar 2000). Shown is a diagram illustrating what customers consider when choosing a loyalty program:

Customers in group A are light users and are unlikely to be attracted to the scheme. Customers in group B are average users and they have the strongest incentive to join. Customers in group C are heavy users and may or may not join a loyalty program.

Loyalty programs have also changed consumer behavior because buyers do not merely focus on the obvious market forces to determine their retailer of choice. Before the advent of loyalty cards, customers would simply go to a certain retail store because of its close proximity to the buyers’ homes. Alternatively, others would think about the prices of the products in the store or their respective quality. While these factors are still crucial to the consumer-decision-making process, now an additional feature has been added; the availability and type of loyalty scheme in the store. Therefore, buyer behavior dimensions have become more complex owing to these changes. Nonetheless, customers cannot compromise on certain core features merely for the sake of earning more points on their loyalty cards. Buyers still give precedence to price or quality (Ehrenberg & Goodhardt 1994). A retail store cannot sell goods exorbitantly or offer substandard commodities, and still hope to maintain a hold on its clients through loyalty programs. The latter strategy can only work as a complementary feature to the above-mentioned basic service qualities. However, in certain scenarios, loyalty programs have minimized price sensitivity. This only comes into effect when the costs of the commodities being bought are relatively similar throughout the entire industry. Therefore, clients have something else that they can aspire to when shopping.

In line with the argument mentioned above, the retail market is currently experiencing polygamous loyalty schemes (Bolton & Bramlett 2000). This means that buyers belong to more than one loyalty program in the same industry or location. Therefore, it is getting more difficult for retailers to create a large pool of exclusive shoppers or buyers who only visit their stores. In mature markets such as the one in this country, copy-cat responses from competitors are common. Therefore, divided loyalties among consumers should not come as a surprise. Usually, such buyers are driven into other loyalty schemes because of certain qualities. They may be attracted by the choices that the rewards offer them. Alternatively, some of them may consider the ease of acquiring those incentives, and this causes them to become polygamous.

Buyers are changing the way they view certain brands. Thanks to loyalty schemes, customers are starting to appreciate the services offered by their preferred retailer because they keep coming back to the same place over again. Therefore, those organizations that have a firm hold on consumers can now enjoy greater dominance in their respective industries. Smaller brands tend to elicit less enthusiastic responses from consumers when they use loyalty programs. However, the same is not true for well-established ones. These large companies tend to enjoy greater returns from the entire retail market (Aaker 1991).

Loyalty programs have increased consumer expectations and demands. Since so many loyalty programs may be available within a certain sector, consumers are likely to choose those ones that possess certain features. Instant gratification is one such factor. Buyers prefer loyalty programs that provide immediate rewards over those ones that take too long to offer them something else. Such characteristics have led to an entitlement mentality amongst consumers. Customers have now come to expect certain rewards for their loyalty. They no longer think of it as something that may or may not occur to them in their lives. In certain retail sectors, loyalty programs can even cause loyalty fatigue because so many other retailers have the same.

As one may anticipate, loyalty programs increase consumer purchases. This may occur simply because customers know at the back of their minds that they will get additional incentives for their buys. Therefore these programs are expanding the size of customer expenditure (Simonson 2002). These individuals are especially interested in certain brands that would have previously been too expensive if no incentive existed. Furthermore, purchases of unconventional products are increasing because loyal customers are better-informed about the nature of goods found in their preferred retailers. Then again, some may simply be carried away by the extra points that they can get from the purchase of certain products. This aspect has a negative effect on consumers because they may end up spending money on unnecessary items. Nonetheless, the feasibility of this effect has been the object of debate in many academic papers. Some scholars argue that the increases in purchases do not emanate from the loyalty programs, but from brand values. Additionally, other scholars claim that it is the incentives from the schemes that increase purchases (Venkatesan & Kumar 2003).

The programs have also enhanced customer relationship management between retailers and customers. Loyalty cards are some of the sources of greater perceived value among buyers. In order for a relationship to flourish between two entities, then both parties must stay committed to one another. If switching is a common phenomenon, then it is unlikely that a strong relationship will develop. Loyalty programs minimize the defection of customers and this fosters their association with the concerned retailer. On the other hand, the loyalty cards also show a firm’s commitment towards its clientele. Buyers know that retailers have to spend a lot of their revenue on the creation and maintenance of these programs. Consequently, they tend to appreciate what those organizations are doing for them and this boosts customer-retailer relationships.

At the onset of loyalty marketing schemes, most customers merely wanted more rewards. They wanted to acquire something, and the loyalty cards were the only method they could use in order to do so. However, this is no longer true today; most buyers want to experience something exceptional, not just get products for free. It is not just about possessions anymore. Clients are now interested in belonging to a retail store that provides value and great experiences. Therefore, the creation of loyalty programs has led to a change in the attitudes and expectations of customers (Ergin 2007).

Perhaps one of the unintended consequences of loyalty programs is the creation of a more vigilant consumer rights body. Some agencies have been created to directly address the exploitation of customers through retail loyalty programs. One such agency is Consumers Against Supermarket Privacy Invasion and Numbering (CASPIAN). The latter agency specifically addresses the issue of information privacy that can be abused by retailers. A number of buyers also object to the alienation that loyalty programs create. Therefore, such opportunities for the collection of personal data from consumers have created retaliatory pressures from consumers who now want to protect themselves.

Theoretical models of business development

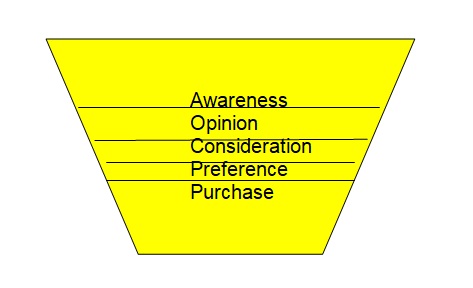

The purchase funnel theory is highly useful in understanding the impact of loyalty cards within the retail sector. This model assumes that when customers are making a purchase, they go through five major processes and these include: awareness, opinion, consideration, preference, and purchase (Thomas 1987). In the first stage, the customer learns about the prevalence of a certain good or service. For loyalty cards, the customer learns about the existence of the program. As the customer becomes aware, he or she will then do some research on the product. In this case, a customer will read other reviews about a certain loyalty program in a retail store. Then a customer forms an opinion about the loyalty program. This should be followed by consideration in the purchasing funnel. Here, the person will have a preference. The customer may aspire to have a certain type of loyalty card over another. Eventually, this will push the client to participate in the loyalty program; that would be the last step, which has been identified as the purchase. Therefore, retailers can control the number of people who use their loyalty program by fully understanding how consumers select loyalty cards.

Conversely, loyalty card providers may also use the purchase funnel model to affect consumer usage of the cards. They could make their retail stores more efficient by capitalizing on various aspects of their consumers’ purchasing processes. For instance, as the customer becomes aware of a commodity, he or she can then do research about the product. The retailer may contribute to this awareness process by furnishing buyers with new information about certain commodities. Retailing firms may do this through customer service calls, emails, social networks, and the like. By simply letting buyers know about some of the end products, the firm can boost repeat sales through loyalty cards. Furthermore, the loyalty card can allow the company to track the purchasing patterns of the consumers so that their marketing strategies are targeted towards the right kind of consumers.

A second theoretical model that can facilitate the understanding of this process is game theory. In-game theory, symmetric games exist when the rewards for following a certain strategy occur regardless of who is playing. In contrast, asymmetric games depend on the players, and the decisions they make (Dutta 1999). The loyalty program can be considered as an asymmetric game. The nature of customers that use it will affect the overall gains that the retail store will get from the scheme. Companies have the option of altering how frequently customers use their loyalty cards based on the game-theoretical model. In the initial stages of use, retail stores have the ultimate opportunity to control how people use these cards if they can understand how those buyers behave at the beginning of the loyalty program. Light purchasers may not view the loyalty card in a positive manner because the rate at which they accumulate points is always slow (Smith & Sparks 2009). Consequently, these clients have to wait for a very long time to get any rewards from the loyalty card.

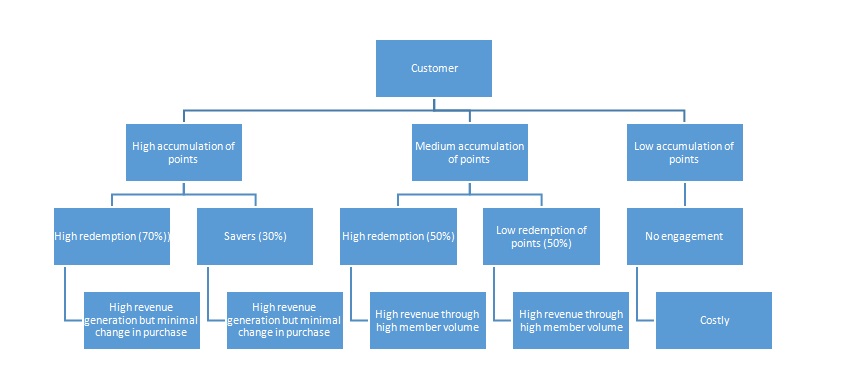

On the other hand, heavy purchasers or average purchasers can get rewards quickly because they accumulate points quickly. However, heavy users get rewards without even trying. Consumer motivational theories indicate that when one is not challenged to seek a reward, then the incentive becomes unimportant (Hilmer & Donaldson 1996). Heavy buyers would not be motivated to increase their purchasing levels because they get rewards so easily. Conversely, the average users would have to purchase slightly more than their usual amount in order to get rewards. This will give them a challenge, and would thus increase the number of purchases in the affected retail store. Therefore, firms must direct their loyalty card marketing campaigns at average buyers, because these are the people who would change their shopping behavior based on the loyalty scheme. The other two types of players i.e. the heavy buyers and light users would not respond positively to loyalty card campaigns. This is because they would have to wait too long for the rewards or would get them too easily (Miller 2003). The game theory says that one must consider one’s players in asymmetric games, and this is true for loyalty card programs. Shown is a summary of the response and effects of loyalty schemes

The game theory can also be utilized as a business development technique for companies when they want to start a loyalty program. It can assist them in determining the right kind of loyalty program for their clients. Since the loyalty card program is considered as an asymmetric game, then the retail chain owners need to know that the type of loyalty card program must relate to their customers. Different clients will be motivated by different kinds of loyalty schemes because their attitudes and motivations vary. For a loyalty card to work, the customers must be able to understand the currency used. If a retail store uses in-store currencies, the clients need to be able to relate to the value of the reward. Here, the retail store owners must understand the kind of buyers that come to the store in order to give them a relevant incentive (Papayoanou 2010).

Additionally, a loyalty reward program needs to be easy to redeem. The customer needs to be motivated enough to seek the reward. More often than not, loyalty program initiators fail to compel their target audiences to seek the reward when they set the threshold too low or too high. When an initiator fails to capture his buyers’ threshold, then he will create consumer indifference towards the program. This creates no change in behavior among the consumers as well as the business. In this regard, both players lose in the game. Alternatively, some companies just make it too hard to get points in their reward scheme. Too often, most business managers or owners get it wrong because they do not understand how far their clients are willing to go to get a reward. If it is too difficult for them to do so, then chances are that they will not go for the loyalty card (Meyer-Waarden 2007). If a loyalty scheme initiator had mastered his audience, then he would know what his consumers would not be willing to do to earn the reward. It is a tough balancing act for the provider because going too far or not going far enough can be detrimental to the organization.

One must analyze one’s customers and offer customized rewards. In fact, it has been found that the most successful programs are the ones that have are more than one way to earn rewards. This means that various activities in the store contribute towards the customer’s points. However, those activities must be in tune with what the different types of clients prefer. A successful loyalty program works by giving clients the flexibility to decide how much they want to earn when they can earn it, and what activities they must do. Customers can be highly satisfied and happy once they know that they have a say in the reward scheme (Lewis 2004). The process of matching customer preferences to available activities and other incentives requires one to really understand one’s client base. Indeed, loyalty programs are asymmetric games because the success of each scheme depends on the customers under consideration.

Consumer-focused products that companies are offering

In order to enhance loyalty, firms are using new technologies to boost their competitiveness. They have introduced mobile phone loyalty programs, which allow customers to enjoy the same benefits that they would have been accorded if they used conventional/ plastic loyalty cards. These firms can issue coupons or vouchers based on mobile phone technology and simply check on serial numbers to confirm authenticity. In fact, it is likely that the mobile phone may be the next replacement of the plastic loyalty card.

Some companies have focused on improving convenience by offering loyal customers better ways of payment. Here, most of them partner with certain financial service providers or other loyalty card schemes in order to reach a wider client base. Therefore, customers can utilize rewards from one loyalty program in another company because these business partners have already been established (Kivetz 2005).

Certain markets are characterized by high fluctuations in prices and these may affect customers quite negatively. Companies in these types of sectors have addressed the problem by giving their loyal card customers credit cards that facilitate rebates on increases in purchases. Normally, those are branded stores that have a set location or geographical niche.

Some companies choose to deliver goods for their loyal customers. These arrangements may depend on the flexibility of the delivery system within the organization. If a company already has such a system in place, then it can offer transportation services to those loyal customers. Performing such actions ensures that the limited resources within a certain organization are utilized effectively.

Other retailers offer discounts to their loyal customers on special occasions. For instance, if someone has a birthday or anniversary, he or she may pay less for a certain item. Normally, firms may prevent abuse of such a system by recording the birthdays or important occasions in their loyal consumers’ lives. Therefore, when the day arrives, then the store can have an additional backup for those loyal shoppers. This adds to the feeling of exclusivity amongst the parties involved (Krafft & Mantrala 2005).

Instead of using loyalty cards, some organizations prefer to give loyal clients vouchers that they can utilize in various settings. These may include restaurants or other eateries. Such a strategy expands customers’ options because they may prefer services over products. Additionally, it adds to the flexibility and appeal of the program under consideration. In close relation with this is offering loyal customers day outs. This may be done in groups or individually depending on what the organization can afford at the time.

Some companies give gift certificates or coupons as a reward to purchasers in their retail stores. These incentives may not necessarily depend on the loyalty of consumers but may simply reward customers for buying large amounts of products from businesses. Organizations must decide what goal they want to achieve when they implement such measures (Seth & Randall 2001).

Other organizations are developing point-of-sale technology for the clients in order to enhance their consumer experiences. This is usually done in order to increase the speed of transaction and thus lead to frequent visits back to the respective store. In tandem with this scheme is data warehousing. Many companies employ such advances in technology in order to enhance the customer experience of their buyers. They use the technologies in order to study the consumption patterns of the buyers and thus create custom-made promotions (Lamb & McDaniel 2008).

Data protection issues that could arise from the use of these cards

Loyalty cards are one of the most direct ways of retrieving information about consumers. They allow supermarkets or retail chains to compile data about a certain person’s preferences (Byrom 2001). To some extent, this can be a positive feature because customers can learn about all the new brands that interest them. However, there is a flip side to this idea; when people’s personal information is collected secretly and used to create profiles about them, then this crosses over into invasion of privacy, and abuse of information. Retail chains usually monitor consumers’ buying behavior through their loyalty cards in order to inform them about special offers. These would be welcome offers if the targeted buyers actually want them. More often than not, such advertisements are highly undesirable and may become a nuisance to the buyers. Customers may choose to opt-out of a given loyalty program owing to those disturbances. Businesses would therefore undermine the very goal that motivated them to start the loyalty program

Some retail chains may take things a step further by misusing or mishandling personal customer information. Certain retail chain stores can post personal information from clients on their websites and this can adversely affect their personal well-being. Hackers or internet theft often occurs through such avenues. Wrongdoers use such open databases to access information that they can use to their advantage. Given the fact that these activities can take place, it is essential to understand the dimensions of the problem. One must know whether the security and privacy concerns are so immense as to minimize customers’ use of loyalty programs. Studies carried out by a Canadian station (CBC) and a British advertising group found that most clients are willing to forfeit their privacy concerns in exchange for the benefits that they derive from the loyalty cards. The Canadian poll found that such clients represented 76% of their population while the UK group found that eighty-five percent were willing to ignore those security risks (Kenley 2005). This means that shoppers are either not duly informed about the dangers of personal data exposure or that the loyalty program providers have done more sensitization than consumer protection groups.

Research reports are quite divergent on this matter. Some clients may not perceive personal database collection as a threat because all the retail store will know about is that they bought a certain thing at a certain time. On the other hand, some highly sensitive clients are disturbed by the issue (Sun 2005). Their biggest concern is that the retail store may sell their personal profiles to other unwelcome business entities. Studies have shown that direct-mail users, telemarketers, and other direct marketers are an unwelcome lot in the shopper’s private space. Several internet users do not like it when an unknown company sends them countless emails about their product offerings. The reactions are equally the same for those persons who call them in the middle of the night to tell them about their latest offers. These actions all represent an invasion of privacy.

Organizations may knowingly or unknowingly dispense information about their clients to other third parties. Deliberate information sharing is highly unethical among retail chain store owners. On the other hand, it is the unintended method that presents the greatest danger to shoppers. Running one’s own loyalty program takes a lot of resources and infrastructure. A company must invest in an up-to-date software and hardware network. This may be tenable for large retail chains that can utilize their wide revenue base to achieve this. Smaller retailers may not always have the resources or the skills needed to manage their own loyalty programs (Waarden 2005). Consequently, most of them may outsource this function to third party loyalty program managers. An example of such an organization includes Alpha cards. This company often promises its clients a well-run loyalty card program. It also records data about buyer preferences and dispenses it to the concerned retail store to use it as it pleases. Any point accumulation is immediately taken to a computer that belongs to the third-party provider. Thereafter, it is transferred to another server, which categorizes and analyses the data further. This means that the provider can know all the suppliers that interact with clients. Such practices pose great dangers to customers’ information when the third party provider lacks thorough security and data protection measures. These profiles can be misused in much the same way as credit card numbers are utilized.

The misuse of information by third-party loyalty providers can be worsened when the staff members of that organization are unethical (Liu 2007). They may deliberately sell the private information to other stakeholders and this is quite dangerous. The same thing can take place among retail stores that do not outsource their loyalty programs. These organizations often place the security of their information in the hands of their staff members. Even IT personnel may create a secret loophole in the company’s database, and may then sell information to interested parties. Unless retail stores instate measures to ensure that unethical staff members do not engage in such behavior, then it is highly likely that buyers will be susceptible to such information breaches.

In instances where customer data is exposed, dire consequences may result. In 2005, a third party loyalty vendor called Valuetec did just this. It did not have a comprehensive security system and went ahead to work with a credit card payment firm known as Card systems. Their intention was to manage the loyalty and gift card programs. This worked by transferring points to their credit cards. The points would be altered when customers bought something from the concerned retailer. This means that numerous Mastercard users’ data was exposed. Estimates indicate that approximately 40 million users were susceptible to credit card theft. On its own, a loyalty program may not cause much financial damage. Information breaches can lead to minor disturbances from unwanted parties. On the other hand, this is not true for those retailers that liaise with credit card or debit card users. Fraudsters and other internet thieves are always on the lookout for such loopholes. This can be quite a dangerous thing to buyers (Shugan 2005).

Retail stores do not behave uniformly when it comes to handling customer data. Some of them may keep their information solely to themselves while others may share it with their trading partners. It is also debatable whether these retail owners actually inform buyers about the possibility of such exchanges or not. Some stores are honest with their clients through their privacy policies. A number of them may state that information sharing can occur amongst third parties. One such organization is Safeway; the firm states that it may share customer information gathered from clients’ personal data with its respective partners in order to enable them to deliver orders. Alternatively, the firm states that it may need to share this information in order to enable service or product payments. These organisations use payment processors that collaborate with the firm. Additionally, this organisation also informs those payment processors that they cannot use buyers’ personal information for their own purposes after completing a transaction.

Some companies may use the information they collect from clients to update customers about certain developments in the loyalty program. For instance, if the client has entered into a contest within the scheme and then he wins, the company would tell him about the win through his or her personal information. As mentioned above, most firms rarely get the right information to the right buyer. They usually make custom-made coupons or other offers to the customers and this is hardly ever welcome (Yuping & Rong 2009).

It should be noted that cases of privacy invasion are likely to increase if the concerned retailer offers employees bonuses for recruiting more loyal customers. It is only the most vigilant customers who can look into the possibility of these occurrences. Few of them rarely ask about such policies, and they may become victimized or exploited by the retail store.

Analysts sometimes argue that if any information violations occur, then the customers are to blame. No one would contact them for personalized offers and promotions if they did not provide that information in the first place. Customers often give out personal information to loyalty card providers voluntarily. Many of them rarely think about the implications of availing their home addresses, telephone numbers, birth dates, and email addresses to such massive institutions. Any problems that may emanate from these sources of data ought to have been anticipated by the shoppers. They need not to complain about something that they could have changed. If information security is such a big concern to an individual, then he or she can simply choose to opt-out of a loyalty card program or choose to keep his or her personal information. This should be a personal choice that few customers think about when they make those purchases.

Perhaps another sensitive data protection issue that emanates from the use of loyalty cards is the use of purchase data to support criminal investigations. Take the example of a person who committed murder with a crude farm weapon such as an ax. If the police carry out an investigation in the suspect’s house, they may find a loyalty card for a certain retail chain. They may call the retail store and ask them whether the concerned person purchased an ax from the store. If the supermarket chooses to collaborate with law enforcers, they may find personal information about the concerned person. The retail owners may confirm that the suspect actually bought the ax from them and if the model of the weapon matches the one used in the murder or the one in the house, then the suspect may be convicted of the crime. In this regard, it can be possible to stop a crime through customer purchase information collected from the loyalty card. On the other hand, if the suspect did not commit the crime and simply lived in an area that required such farm implements, then he or she may be wrongly punished for the crime. The fact remains that it is illegal for law enforcers to use information from personal databases. The constitution specifies individuals’ right to protection from information use from private databases. However, this may not necessarily undermine the occurrence of these collaborations. Some retailers may not know about such laws or may blatantly break those laws (Taylor & Neslin 2005).

At a deeper level, customers are highly susceptible to certain disadvantages that relate to their purchase behaviors. When a retail store creates a personal profile about a person, it can be possible to learn about the psychological characteristics of that buyer. If the information is not secure, then another company that offers services employs or interacts with the concerned buyer can use this information to minimize the person’s life chances. If a person frequently purchases sleeping pills from a pharmaceutical store with a loyalty card program, then that may indicate that the person is addicted to the drugs or he or she has a health risk. If the profile information is stored poorly, then a health insurer may access it and deduce that the individual is a bigger health risk to the firm. He or she would have to pay a higher health premium than if that information had not been exposed.

Alternatively, if a single worker buys condoms on a daily basis from a retailer, and the information is unethically accessed by an employer, the company owner may think of his work as a liability. He or she may be put through an unexpected physical evaluation. This could be detrimental to a person’s career chances if an undesirable disease is found. On the other hand, if supermarkets and other retailers are careless about the private data they have collected about a customer, an overambitious custody lawyer may get information about the persons’ buying habits. If the person purchases excessive amounts of alcohol, then the lawyer may argue that the individual is a failed parent. This would mean losing custody of one’s children or may create such dire consequences. The truth remains that having a ‘Big brother’ somewhere in the form of loyalty cards can always pose the risk of information abuse. Such loopholes can alter people’s life chances or safety.

Shortcomings of loyalty cards to consumers

A number of consumers have argued that loyalty card programs only provide temporary benefits. They claim that retail stores first focus on their profit margins before rewarding their clients. In fact, some buyers claim that stores with loyalty programs have higher prices than the ones without. These retailers may also alter prices at a very gradual level such that customers may not easily recognize it. What is even worse is that non–loyalty members are forced to pay the same prices as loyalty members even when they do not enjoy the benefit of rewards from the program.

One may also argue that loyalty cards have created a phenomenon of exclusivity in the retail sector. As explained earlier, there are certain categories of buyers that are highly responsive to loyalty programs. Although heavy buyers rarely have the incentive to use a loyalty card, numerous retail store owners still target them for most promotions. Additionally, moderate shoppers have the incentive to increase their purchasing behavior in order to earn more points. Therefore, retail store administrators often target these categories of shoppers when marketing loyalty schemes or any new products. The infrequent purchasers are left out of the equation and this perpetuates a cycle of exclusion. The retail sector then transforms into a capitalistic machine that eliminates clients on the basis of their rate of return (Smith & Tzokas 2004).

Certain consumer-rights groups object to the underlying values that shape the loyalty reward scheme. Firms are often encouraged to increase consumer commitment to the loyalty program. What counts is whether the customer believes he is getting value for money in the reward; it does not matter whether this is really true. This is a conspiracy against the consumer by such retail firms.

Some retailers prefer to give clients a disincentive for opting out of a loyalty program. For instance, one may have to pay extra fees, and this may discourage some shoppers from getting out. In other stores, it may take too long or maybe too complicated to get out of a program. Besides that, one may have opted out of a loyalty program but he or she may still get offers on promotions from the retail store’s trading partners or suppliers. The store may not bother to inform the other trading partners about a client’s exit from the program. This means that customers have very minimal say in the way their personal information is used.

Effects of consumer loyalty programs on retailers

Studies indicate that numerous businesses in nonsaturated markets benefit financially from loyalty schemes. However, the results depend upon the nature of customers that frequent the store. If most buyers are moderate users of the store, then loyalty programs will cause them to increase their purchase frequency. However, if the store mostly has infrequent or heavy shoppers, then a loyalty program will not cause them to increase their rate of visiting the store. Since it is likely that a store will have more moderate shoppers than light or heavy shoppers, then loyalty cards work well for these organizations by increasing the number of transactions undertaken by the concerned buyers. Shown is a diagram of the effect of loyalty programs on purchase frequency.

Other analyses also show that retail stores in developing markets also benefit from an increased transaction size after introducing these programs. Lighter buyers will be prompted to experiment with other program categories and thus increase the amount of money they spend in a retail store. However, this does not mean that light buyers will increase the rate at which they visit those stores. On top of that, moderate buyers are likely to buy more things and thus increase their transaction sizes as well. All these returns will cause an increase in a retailer’s profit margins. The following graph is an illustration of the effects of these programs on transaction size:

Perhaps the most important consequence that one must consider when looking at the effects of loyalty cards is their influence on customer loyalty. More loyal customers are likely to come to that specific retail store more than nonloyal clients if there is minimal competition in the market. They may go out of their way to shop in that business and may not defect even when other promotions occur in other companies. Although a number of customers may respond differently to loyalty programs, in developing markets most of them become loyal to stores if they own a card there. They often considered the overall incentives that they can gain from a particular loyalty program. Once they select the best one, they will usually stick to it. Nonetheless, the infrequent or light shoppers rarely remain loyal to a retail store even if they own a loyalty card. Additionally, these cards allow greater relationship building between the retail store and the client, and this enhances the positive effects on the business.

However, the effect of loyalty cards changes tremendously when the targeted buyers have multiple cards especially from directly competing retailers. In a highly saturated retail market with too many loyalty schemes, the dynamics may change tremendously. Some customers may choose to play the cards against each other in order to take advantage of the greatest offerings. Similarly, some may focus on retailers’ prices when choosing stores. Large supermarkets such as Tesco have highly loyal customers even when their competitors own different kinds of offers. Furthermore, if the concerned company takes the time to analyze its customers well, then chances are that the loyalty cards will create positive results. Only those companies that focus on the fundamental issues of loyalty can get the right results. Massive investments in market research, technologies, and others can do this relatively easily. Therefore, the effect of loyalty programs on developing markets is much higher than in saturated markets that bombard their customers with plenty of loyalty schemes (Noordhoff, C & Odekerken-Schroder 2004).

The relationship marketing principle is what causes most firms to try loyalty programs. However, in saturated markets, not all of them may get real value based on this principle alone. Firms must honestly evaluate the development costs, the amount they will invest in running the programs as well as the amount of money they need to use in marketing the program. They must look at the benefits or increases in revenue that will result from the program. Only when this is done can firms truly benefit from such an arrangement. One may say that loyalty programs in developed markets are more complicated than in growing ones as they depend on a number of conditions for their success (Kopalle & Scott 2003).

A number of researchers actually question the effectiveness of these schemes in places such as the UK and the US. More than three-quarter of the loyalty market have more than one card. Furthermore, most researches that reveal positive outcomes of these incentives tend to focus on banking or airline loyalty schemes. These are industries that have high exit barriers. Additionally, they often require customers to get into contracts with their sellers. Consequently, a loyalty program would have a different effect here than it would in the retail sector. The latter industry is characterized by low retail margins. Additionally, supermarkets have limited platforms for increasing the amount of value that they offer consumers. This means that their ability to tap into the loyalty program incentive is restricted. Unless a retailer has a well-organized loyalty scheme that is highly innovative and suits its market, then the benefits that come from such an arrangement may not be so substantial in a developed or saturated market like the UK (Yuping 2007).

In addition to the above-mentioned result, companies need to accommodate all the costs that come with managing their own loyalty program. This sometimes pushes some firms to increase prices, and thus keeps would-be loyal consumers away from the store (O’Brien & Jones 1995).

Therefore, most businesses in mature markets have very good intentions when setting up their loyalty programs. However, few of them rarely think about the objectives. In the current retail world in the US or UK, one cannot purport that one has a better or easier loyalty card program as everyone else does the same. The sense of entitlement among consumers implies that retailers have to do much more than anticipated. This will affect their bottom-line negatively (Ehrenberg 2005).

Conclusion – Whether loyalty cards are a worthwhile venture

For consumers, loyalty cards appear to be a worthwhile venture because they offer them free rewards, a sense of belonging, better services from their usual retailer, the expediency of payments, better information on products, better brand awareness, and more innovation. Conversely, these loyalty schemes lead to higher consumer purchases among buyers, higher rates of price increases, and exclusivity of infrequent buyers. Furthermore, they may result in data protection issues such as exposure of personal data in the company website, creation of personal profiles that can be shared with retailers’ business partners, the intrusion of one’s privacy through unwanted promotional offers, and use of the purchasing profiles by undesirable third parties such as police officers, custody lawyers or health insurers. These could cause severe psychological and financial harm to owners of the loyalty program. Nonetheless, these privacy concerns may not be as severe since the law protects buyers against exploitation by these third parties. Furthermore, the benefits received from the loyalty cards by clients are far more likely to occur than the risks.

For businesses, loyalty cards may seem like a good idea because they may increase customer purchases. However, in developed markets, the actual increases in sales are outweighed by the costs of creating, promoting, and managing the loyalty program. Furthermore, they only increase loyalty levels among a small demographic of consumers. Customers may own multiple loyalty cards and take advantage of the various schemes in their markets. The success of these schemes for business requires retailers to do a comprehensive study of their customer base in order to offer them customized solutions. This high effort may not always be done by most institutions and can thus lead to failure. For retailers in mature markets, loyalty cards are not a worthwhile investment.

References

Aaker, D 1991, Managing brand equity, Free Press, New York.

Bolton, R & Bramlett, K 2000, ‘Implication of loyalty program membership and service experience for customer retention and value’ Journal Academy of Marketing Science, vol. 28 no. 16, pp. 180-193.

Byrom, J 2001, ‘The role of loyalty card data within local marketing initiatives’, International Journal of Retail and Distribution and Management, vol. 29 no. 7, pp. 13-26.

Dutta, P 1999, Strategies and games: Theory and practice, MIT Press, Massachusets.

Ehrenberg, A 2005, ‘If you are so strong why aren’t you bigger?’ Admap, p. 13-14.

Ehrenberg, A & Goodhardt, G 1994, ‘The after effects of price related consumer promotions’, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 34 no. 4, pp. 11-21.

Ergin, P 2007, ‘Impact of loyalty cards on customers’ store loyalty’, International Business and Economics Research Journal, vol. 14 no. 3, pp. 97-105.

Hilmer, F & Donaldson, L 1996, Management redeemed, Simon and Schuster, New York.

Kenley, R 2005, ‘Loyalty is pointless – or is it?’, The Wise Marketer, p. 15.

Kivetz, R 2005, ‘Promotional reactance: The role of effort-reward congruity’ Consumer Research, vol. 31, pp 725-736.

Kopalle, P & Scott, A 2003, ‘The economic viability of frequent reward programs in a strategic competitive environment’, Review of Marketing Science, vol. 1 no. 15, pp. 1-39.

Krafft, M & Mantrala, M 2005, Retailing in the 21st Century, Springer publishers, Heidelberg.

Lamb W & McDaniel, C 2008, Essentials of marketing, Cengage Learning, Santa Barbara.

Lewis, M 2004, ‘The influence of loyalty programs and short term promotions on customer retention’ Marketing Research Journal, vol. 43 no. 3, pp. 281-292.

Liu, Y 2007, ‘The long term impact of loyalty programs on consumer purchase behaviour and loyalty’, Marketing Journal, vol. 71 no. 4, pp19-35.

Miller, J 2003, Game theory at work: how to use game theory to outthink and outmanoeuvre your competition, McGrawhill, New York.

Meyer-Waarden, L 2007, ‘The effects of loyalty programs on customer lifetime duration and share of wallet’, Retailing Journal, vol. 83 no. 2, pp. 223-236.

Noordhoff, C & Odekerken-Schroder, G 2004, ‘The effect of customer card programmes: a comparative study in Singapore and the Netherlands’ International Journal of Service Industry Management, vol. 14 no. 4, pp. 17-38.

O’Brien, L & Jones, C 1995, ‘Do rewards really create loyalty?’ Harvard Business Review, vol. 12 no. 5, pp. 75-82.

Papayoanou, P 2010, Game theory for business, Probabilistic publishing, London.

Peppers, D & Rogers M 2004, Managing customer relationships: a strategic framework, John Wiley and Sons, New York.

Reinartz, W & Kumar V 2000, ‘On the profitability of long-life customers in a noncontractual setting: An empirical investigation and implications for marketing’, Marketing Journal, vol. 64 no. 8, pp. 17-35.

Seth, A & Randall, G 2001, The grocers: the rise and rise of the supermarket chains, Kogan Page Publishers, Chicago.

Shugan, S 2005, ‘Brand loyalty programs: Are they shams?’ Marketing Science, vol. 24, pp.185-193.

Simonson, I 2002, ‘Earning the right to indulge: effort as a determinant of customer preferences toward frequency program rewards’, Marketing Research Journal, vol. 39 no. 8, pp. 155-170.

Sun, B 2005, ‘Promotion effect on endogenous consumption’, Marketing Science, vol. 24 no. 3, pp. 430-443.

Smith A & Tzokas N 2004, ‘Delivering customer loyalty schemes in retailing’ International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, vol. 32 no. 5, pp. 53-60.

Smith, A & Sparks, L 2009, ‘Reward redemption behaviour in retail loyalty schemes’, British Journal of Management, vol. 20 no.2, pp. 204-218.

Taylor, G & Neslin, S 2005, ‘The current and future sales impact of a retail frequency reward program’, Retailing Journal, vol. 81 no. 4, pp. 293-305.

Thomas, B 1987, ‘The purchase funnel: An historical perspective. Current Issues and research in advertising, 251-295.

Uncles, M 1996, ‘Do you or your customers need a loyalty scheme?’ Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing Journal, vol. 2 no. 4, pp. 335-340.

Venkatesan, R & Kumar, V 2003, Using Customer lifetime value in customer selection and resource allocation, Marketing Science Institute, Cambridge.

Waarden, B 2005, ‘Loyalty programs and their impact on repeat purchase behaviour’ Marketing Journal, vol. 15 no. 6, pp 241-256.

Yuping, L & Rong, Y 2009, ‘Competing loyalty programs: impact of market saturation, market share and category expandability’, Marketing Journal, vol. 73 no. 5, pp. 93-108.

Yuping, L 2007, ‘The long term impact of loyalty programs on consumer purchase behaviour and loyalty’, Marketing Journal, vol. 5, pp. 19-25.