Descriptive write-up

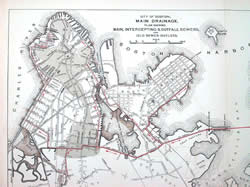

A number of plans have characterized the Charles River historical trajectory. Most of the plans have been implemented while others faced challenges and remained unimplemented.

Initially, the Native Americans used the Charles River for transportation and fishing. However, the early European settlers made plans to use the River for industrialization. The plans were implemented and by 1640, the River water was used to power industrial settlers’ mills.

Implementation processes of the European settler plans saw the building of 20 dams to generate power to run industries. As a result, the River was highly polluted by poor sewerage disposal and altered flow of River water.

Plans to transform the Charles River Basin from pollution and tidal waves were initiated by visionaries like Charles Eliot. Charles Eliot learned landscape architecture from Fredrick Law Olmsted. The plan involved convincing politicians to relocate industries initially constructed in the Lower Charles. Further, a dam was constructed at the mouth of the River transforming the otherwise polluted tidal River mouth into a freshwater man-made basin.

The Massachusetts Water Resources Authority has for a long time made elaborate plans to improve the project especially sewerage disposal. Most of the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority plans have been implemented (Kubiak, Smoske and Lam 2015).

The Massachusetts Department of Conservation sponsored a plan to allow people to gain access to the central park with more ease by constructing bike paths and pathways.

Planning and implementation of the project in relation to broader city historical trajectory

As early as 1634, Europeans had settled in Boston, and they needed water to run the industry they had established. Therefore, they constructed a number of dams along the Charles River. Unfortunately, the dumping of waste in the River became rampant and, therefore, the River was extremely polluted.

In 1908, a counteractive dam was constructed to alleviate the numerous environmental problems associated with previously constructed dams. The dam was constructed between Boston and East Cambridge (currently near the Museum of Science) lessening sewage menace by covering tidal flats. As a result, the estuary that existed at the River mouth was replaced by a basin where the River water settled.

In 1978, a new dam was constructed to replace the dam constructed in 1908. The dam was intended to control floods and allow free fish movement.

In 1988, the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority made a plan of creating a Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) to control the illegal discharge of sewer into the River.

In 1995, EPA made an intervention to the uncontrolled CSOs, and it issued orders to municipal authorities to eradicate unlawful sewer discharges. In the same year, EPA did an assessment and the score was unsatisfactory. Consequently, Clean Charles Initiative was initiated.

In 1997, the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority made a long-term plan to initiate the reduction of the level of sewerage discharge by shutting down seven CSOs.

In 2000, the Deer Island Plant tunnel was completed expanding the sewer treatment plants and, therefore, improving the quality of water.

In 2005, the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority realized the implementation of the 1997 CSO plans, and the number of gallons of discharged sewerage reduced drastically.

In 2013, the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority in conjunction with Town of Brookline completed a sewer treatment project further lowering the amount of untreated sewer discharge

Political actors, social actors, public and private institutions

Towards the end of the 19th century, the then Massachusetts governor, William Eustis Russell saw the need to redeem the River from pollution and, therefore, he initiated the Charles River Improvement Commission. The Commission worked with architectures such as Charles Eliot to come up with the restructuring project. The politicians influenced the relocation of some of the industries away from the River shore. More politicians have fought for the conservation of the Basin.

Social actors have been actively involved in the project, especially raising concerns regarding pollution in the Charles River Basin. Some have expressed their concerns through writing article in the dailies.

The America Society of Landscape Architect is among the institutions that have greatly contributed to the planning of the Charles River Basin. The association has fought for sustainability of the River Basin. For instance, the association facilitated the preparation of a master plan to take the project through to the 21st century. In this plan, groups of people from different occupations and social groups were involved, including volunteers, experts in landscape architecture and urban design, and the regional park authority client. The public was highly sensitized to the Charles River Basin conditions and the environmental concerns (United States Environmental Protection Agency 2015).

Outstandingly, the environmental protection agency (EPA) is one of the public institutions that have been actively involved to ensure that the Charles River Basin is free from pollution. As such, EPA has sensitized the public on environmental concerns even requiring people to clean up the River. Other notable institutions include Massachusetts Environmental Police, Cambridge Conservation Commission, and Massachusetts Department of Conservations and Recreation among others.

Private institutions have actively participated in the process of ensuring that Charles River Basin is pollution free, especially for recreation purposes. Private institutions include Charles River Watershed Association, Conservation Law Foundation, and Charles River Cleanup Boat among others.

Timeline

Charles River is generally short, narrow and occupies about 308 square miles of land area with about 80 books and streams and big aquifers that drain into it (Charles River Watershed Association 2016). Several man-made lakes and ponds are found near the river while it flows through several communities in twists and turns.

Before the 1900s

Charles River has an extremely long history dating back to 4000 BC when the Native Americans first occupied the watershed noticed through the discovery of fish weirs in Back Bay (United States Environmental Protection Agency 2015). Before the 19th century, Native Americans used the River for fishing, means of transportation and as an important route that connected New England and Massachusetts. The early European settlers however harnessed the River for industrial growth. In fact, the first dam was constructed in 1640 to provide power for the mills. After a short period, more than 20 dams were constructed along the River to provide electricity for the mills.

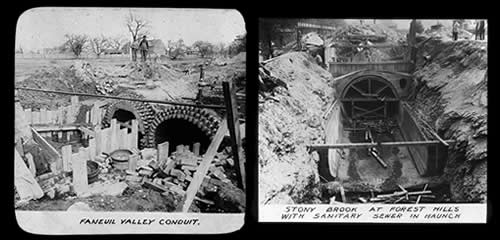

Hence, the first critical human activity of dam construction led to a slow-flowing river and rendered the River ineffective in self-cleansing because of several flow interruptions. Further, it caused massive flood in open fields, affected pasture, and hindered movements of people and goods. The dam also resulted in extended shorelines and increased areas covered by water. Specifically, the Moody Street Dam constructed in 1814 found in the Lake District resulted in several bays and inlets through the ‘mill pond’ (United States Environmental Protection Agency 2015). Today, thousands of boaters and tourists visit this area for its scenic view.

Mills and dams, nonetheless, were responsible for the pollution of the River leading to declining fish population. By 1875, there were about 43 mills stretching between Boston Harbor and Watertown Dam.

The Period of Transformation of the Basin between 1900s and 1960s

A landscape architect, Charles Eliot led other reformists to clean up the River. Eliot noted that it was imperative to construct industries far from the Lower River and construct a dam to control tides. This work resulted into the completion of Charles River Basin 1908. The rotting tidal estuary became now the reputable city waterfront park. In fact, the Basin substituted Norumbega Park for recreational activities, including public sailing, rowing, and yacht clubs among others.

The Basin was the first major improvement on the River. A water supply was constructed to supply Quabbin and Boston areas in the 1930s. This engineering accomplishment ensured that local areas could sufficiently get constant supply of water to support the growing Metropolitan Boston.

The abundant water supply led to rapid growth of the local population, which in turn created challenges of managing domestic, municipal, and industrial waste materials. Once again, the River could not sufficiently cleanse itself. Besides, poor rainfall noted in 1960s made the rate of population severe. The River was once again in a sorry state.

Citizens’ Intervention between 1960s and 1980s

Given the massive rate of pollution of the River, the public responded by creating Charles River Watershed Association (CRWA). The CRWA is responsible for major cleanup and other protection goals for the River while collaborating with relevant stakeholders, including the public and the local, state, and federal agencies.

Rather than constructing more dams to control floods between 1960s and 1970s at envisioned by the US Army Corps of Engineers, the CRWA intervened and proposed the preservation of 8,000 wetland acres under the project, Corps’ Charles River Natural Valley Storage. This program resulted in flood controls, the creation of natural habitat, a source of water, and a pollution filter.

The Clean Water Act 1972 led massive changes in the use of the River. For instance, the CRWA promoted the development of new wastewater plants in the upper pasts of the River and advocated for the strict regulation of industrial discharge into the River.

In 1978, a New Dam was constructed to replace the old dam between Boston and Cambridge with the purposed of controlling flooding.

The CRWA has led several successful cleanups, closure of landfills closed to the River and ensuring compliance of polluting manufacturing. In fact, the Conservation Law Foundation action of suing both state and federal agencies led intense cleanup activities of Boston Harbor in 1983.

The Massachusetts Water Resources Authority (MWRA) was forced to invest in modern, extensive sewer system to control discharge into the River.

After 1980s

Major activities on the River after 1980 have resulted into conservation and improvement efforts driven by major stakeholders, including EPA, MWRA, the Department of Justice, and CRWA among others.

In 1988, the MWRA developed a program to monitor sewer management. The River has become cleaner, suitable for swimming and the populations of fish have increased. The Clean Charles Initiative was started in 1995 with a report card grade D while EPA wanted local authorities to control illegal discharges. In 1997, MWRA got an approval for the closure of seven sewer overflows, and by 2000, all known illegal connections were to be eliminated by the year 2005 – Earth Day.

Further, Deer Island Sewage Treatment Plant and other tunnels were completed in 2000. This feat increased the capacity for waste treatment, curtail overflows, and enhance water quality.

In fact, MWRA had attained most of its 1997 sewer overflow goals. In 2012, Boston Water & Sewer Commission has focused on all illegal connections and sewer overflows. It attained grade B in 2005 while in 2006, Stony Brook was completed to ensure constant supply of bacteria to lower sections of the River.

EPA and Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (MassDEP) establish Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) created Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) to lessen the concentration of phosphorus in the River. The local authorities must continuously conduct studies to eliminate any challenges facing the River as agreed in 2008 while a decree passed in 2012 compelled BWSC to locate and remove all illegal connects. In 2013, MWRA and Town of Brookline reached a deal on sewer separation project to reduce overflow and discharge to the River. The last assessment in 2014 resulted in grade B+.

Finally, CRWA has increased its focus on shoreline erosion, paved areas runoff, metals, oil, fertilizer, pesticides, and salt among other pollution agents.

Visual

Photographs of the site

Critical Narrative on Charles River Basin – issues, sites, actors, and institutions

Before massive settlement of human and various human activities on the River were witnessed, the River flowed freely through its natural ways while rainwater flowed down the drain or absorbed into the ground to clean pollutants. Today, however, concerned stakeholders have noted the negative impacts of storm water that runs from the roofs and other public places while carrying away debris, chemical fertilizers, and other deadly pollution agents into the River (Conservation Law Foundation 2015). Consequently, highly contaminated dirty water drains into the River, Boston Harbor and into other sections of the River.

It has also been observed that the toxic algae that thrive in the presence of phosphorus mainly collected by storm water are major threats to Charles River Basin (Conservation Law Foundation 2015). Specially, elements contained in the soup, including phosphorus are responsible for feeding algae, resulting into massive growth and outbreaks. Consequently, the River is often exposed to fish poising and unsafe boating activities. Phosphorus is also known to feed dangerous invasive water plants such as water chestnuts, which eventually kill native species of plants. Hence, the water quality continues to decline in the entire Charles River watershed. It is, however, imperative to recognize that pollution from storm water and phosphorus can be completely controlled through effective application of the Clean Water Act by EPA (Conservation Law Foundation 2015).

EPA knows all the major polluters of Charles River Basin that include small-scale farmers, commercial, industrial, and residential areas. These bodies contribute significant amount of phosphorus (about 62%) that drains into the River.

In addition, it has also been noted that the River continues to face critical challenges related to control and management of diffused sources of pollution, including septic systems, some farming activities and, of course, climate change.

From architects’ perspective, sites such as Back Bay, which account for some of the most important estates in the country, face critical challenges from climate change. Architects have recognized that Back Bay is vulnerable to effects of climate change specifically from flooding from Charles River Dam and Fort Point Channel if its current infrastructure is not altered (The Kresge Foundation 2014). Back Bay, considered the most walkable mixed-use neighborhood in the country, consists of retail, residential, civic buildings, offices, and open spaces developed with massive access routes to the city, which include foot, mass transit, bicycles, and cars among others. Back Bay is designed as the most valuable real estate in Boston. It was designed on marshland recovered in the 19th century. This land is roughly four feet above the high tides (The Kresge Foundation 2014).

Architects concur that effective evaluation of climate change impact is vital to planning of the city and Charles River Basin. The US Army Corps of Engineers designed the Dam in the period of 1970s based on the assumption that the sea level was projected at the rate of 0.6 feet every century. In 2014, however, the National Climate Assessment observed that the sea level could rise from one to four feet by the year 2100 based on the accumulation of greenhouse gas emissions.

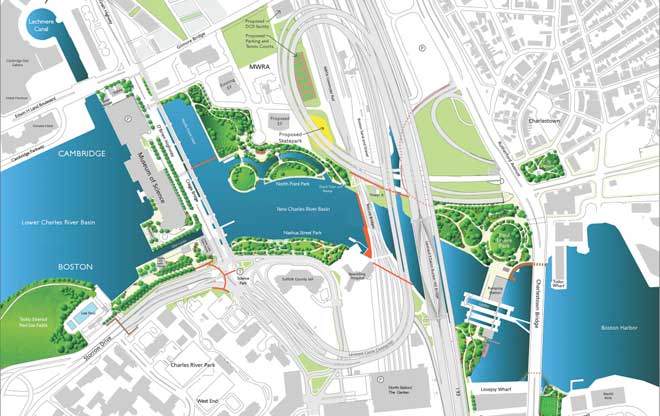

According to information obtained from American Society of Landscape Architects 2016, the New Charles River Basin is based on a thorough environmental protection effort, and the Third Harbor Tunnel and Central Artery financially supported the project. “Bechtel/Parsons Brinckerhoff and the Boston Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) managed the Project jointly” (American Society of Landscape Architects 2016, 1). Metropolitan District Commission is now the DCR. The Project was started in a 3-year master planning while the first construction of the parkland was initiated in 1995, and it is almost completed (American Society of Landscape Architects 2016).

The Project joined “the River Basin Esplanades located in Boston with Cambridge in the Boston Harbor” (American Society of Landscape Architects 2016, 1). Carr, Lynch, Hack and Sandell were responsible for the master plan for the New Basin, which also included five more parks that are new and foot bridges (American Society of Landscape Architects 2016). In addition, Carr Lynch and Sandell with Oehme van Sweden Associates designed Paul Revere Park and North Point Park; Halvorson Design Partnership designed Nashua Street Park and the Prince Street Park; Childs Engineering and Carol R. Johnson Associates were responsible for Lovejoy Wharf Walkway, and the City Square Park (American Society of Landscape Architects 2016).

Actors and Institutions Involved

Charles River Basin has many major stakeholders. First, architects have played critical role in the design of the formation of the Basin and subsequent improvements. After the work of Eliot, architects, including the US Army Corps of Engineers, architects, and engineers have progressively improved the dams to control flooding and water levels. Today, architects are concerned with emerging issues related to climate change. For instance, architects must find new ways to introduce new experiences for urban Boston by integrating new canals to embrace and celebrate living with water just like in Amsterdam and Venice. They must manage water assets and control threats emanating from rising sea levels above the dam. In addition, architects must work on improving green infrastructure, means of sustainable transportation, preserving historical structures and characters, and spearheading the development of new policies and partnerships for the Basin.

The federal, the state, and local governments through their agencies and EPA have formulated new laws and regulations to control pollution and conserve the Basin. These laws, if implemented effectively, can ensure high quality of the River water.

The public through CRWA has contributed significantly to the development of the Basin. The CRWA plays significant roles in research, clean up and conservation efforts. Most of its works are supported with evidence.

In addition, other efforts to improve the Basin have emanated from conservancy groups and scholars.

Overall, partnership is vital for the Basin. That is, the Basin requires strong leadership that can bring all stakeholders to work together and improve the Basin.

Important Issues Raised

The current major issue facing architects and engineers is the uncertainty, timing and the extent of the rising sea levels. The NOAA’s tide indicator located at Boston Harbor shows the sea level increased by one foot in the past century. However, it is projected that the level may rise with from a range of one to six feet by the end this century. This range is vital for architects in terms of design concepts.

Boston city was planned to be a mixed-use city with integrated amenities. However, the rising water levels know no limit and may consume current infrastructures, boundaries, and even private property. Thus, architects must ensure that all stakeholders cooperate to address emerging issues triggered by climate change.

Designers must continuously work on new systems to separate sewer and storm channels. These projects however require investments. Architects and engineers can then design and develop resilient infrastructures. Engineers must work on new designs to develop resilient infrastructures for gas, electricity, and water supplies to meet demands of residents amidst new challenges. In addition, engineers and architects must ensure that the subway systems are waterproof, which requires significantly diverse range of technical knowledge for effective design and implementation.

The architects will also ensure that the built environment maintains its values. Hence, upgrades and execution of the project for historic sites, new buildings, transport infrastructures, open spaces, and utility infrastructures among others must account for value preservation.

Others issues related to water quality and stream flow are also of interests to stakeholders. Thus, it is imperative to understand the possible causes of low flows of Charles River watershed. Attention must also focus on the rising quantity of blue-green algae in the River. In fact, since 2006, CRWA has focused on working with other stakeholders to eradicate algae to avoid health threats.

Sediments and other chemicals deposited in the Basin can result in serious and long-lasting environment issues and public health challenges.

It is noted the EPA has not effectively applied environmental laws to protect natural resources and built environment. EPA knows all the major polluters of Charles River Basin, specifically those that discharge storm water. The agency has the legal authority and duty to protect the environment and protect the public. Based on the Clean Water Act, private organizations should obtain a license to allow them to discharge storm water into the River. Although it has been proven that a license works in controlling illegal storm water discharge and, it rapidly leads to a decline in the discharge, EPA has not been effective in enforcing this law.

Reference List

American Society of Landscape Architects. The New Charles River Basin. 2016.

Charles River Watershed Association. Charles River History. 2016.

Conservation Law Foundation. “Defending the Charles: Closing the Clean Water Gap and Making All Polluters Pay.” The Journal of Conservation Law Foundation 20, no. 2 (2015): 1-7.

Kubiak, David A, Nadine S. Smoske, and Christopher Lam. Massachusetts Water Resources Authority. 2015.

The Kresge Foundation. The Urban Implication of Living with Water. 2014. Web.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. Charles River Timeline: A History of Human Impacts on Charles River. 2015. Web.