Background

Prior to the 19th century, art was vibrant. Artists prepared various forms of artwork for both commercial purposes and personal enjoyment or aesthetic value (Acconci & Acconci Studio 2004, Para. 4). The society was appreciative of precious artwork such as Leonardo da Vinci’s Monalisa and Van Gogh’s pieces.

Part of their allure was the fact that these pieces were extremely rare. Only a handful of collectors could afford the exorbitant prices set for each piece because similarly, only a few artists of the time could reproduce with skill and precision copies of the originals worth a collector’s money (Bearden 2003, Para. 3).

Consequently, art was remarkable, and the few artists whose talents were undeniable reveled in the glory that their work gave them. However, in the 19th century, the art world experienced a few fundamental changes. The industrial era triggered most of these changes as people began to generate more income and consequently, more could afford to purchase rare art pieces (Berry 2010, Para.1).

With this unprecedented increase in demand, artists had to keep up somehow, and individualistic hand printing was far too strenuous and time consuming. Ironically, not an artist but a playwright or dramatist came up with the idea and technique of lithography. He was seeking for a printing technique that would enable him to produce multiple copies of his play (Boone 2009, Para. 5). Alois Senefelder, an Austrian dramatist in Bavaria invented the technique of lithography.

Initially, the only available printing techniques were relief printing, which involved carving out the surfaces of flat surfaces and applying ink on the projecting surfaces, and then pressing a paper onto the inky surfaces to provide images (Babb 1998, 34). The other technique, intaglio, or engraving involved making indentations on a flat surface and filing these with ink, and then using an uncompressed paper to get the image by sucking up the ink from the indentations (Close 2005, 24).

Both of these methods were tiresome and could not satisfy the demand for reproduced artwork, hence the use of lithography and photography to complement these. The result was that artists made more reproductions over shorter periods using far less labor. Whereas this seems like a positive development, it had repercussions, as well. The generic artist almost died.

Thesis

During this time, as is also the case in contemporary art circles, artists could barely survive on the benefits that accrued from their various works because it took most of their lives before the world recognized or even acknowledged their work (Cornell 1995, 102). Consequently, money was not an incentive to produce art and mostly, the source of most of these artists’ ambition was the spirit of competition or restrained curiosity and interest.

Most of them lived on commissions, which were rare and meager, so they had to find alternative means of income in other professions such as teaching and farming or even industrial labor (Dante 2007, Para. 3). For this reason, when the reproduction techniques of lithography and photography came up, most of the artists at the time viewed this as a gold mine.

It was an avenue for them to produce multiple copies of either their own personal work or that of other artists. Moreover, these techniques made it possible for the artists’ works to get to the public much easier. Newspapers and televisions could now illustrate artists’ works, and the public could order for various pieces (Dali 1958, 45).

The result of this was that artists produced far less original pieces focusing more on mass production to satisfy the demand. Consequently, art almost died. However, some artists sought to preserve the sanctity of original production, as opposed to mass production. These artists insisted on doing their own drawings and paintings as a way of rebelling against the new culture of mass production (DePaoli 1994, 34).

Nevertheless, they were not so many as to halt the progress of lithography and photography altogether. The impact of their efforts was minimal because they too in trying to make a living had to conform to society’s demands, which could only be satisfied by applying lithography and photography among other production means (Digital Art Practices & Terminology Task Force (DAPTTF) 2004, Para. 2).

As a result, although their efforts did not stall the advancement of lithography and photography, it at least preserved some artistic patriotism to the traditional methods of painting and drawing.

Development of Lithography

Lithography as a printing technique came into operation in 1796, when Alois Senefelder (1771-1834), an Austrian dramatist in Bavaria sought to produce multiple copies of his plays through mass reproduction (Digital Art Practices & Terminology Task Force (DAPTTF) 2004, Para. 2).

As noted above, prior to lithography, the dominant printing techniques were relief printing and intaglio or making engravings on surfaces and filling these with ink, and then printing. Both relief printing and intaglio featured printing on a varying surface (Doisneau 2001, Para. 3). Lithography involved printing on a flat surface. The basic principle, which informs lithography, is the mutual or simultaneous repulsion of grease and water.

The artist draws an image on a fine, flat piece of limestone using a greasy crayon and then wets the limestone with water. Next, he applies a greasy ink on the wet surface, and the parts with the greasy crayon absorb this ink while those without crayon markings repel the ink because they are wet with water.

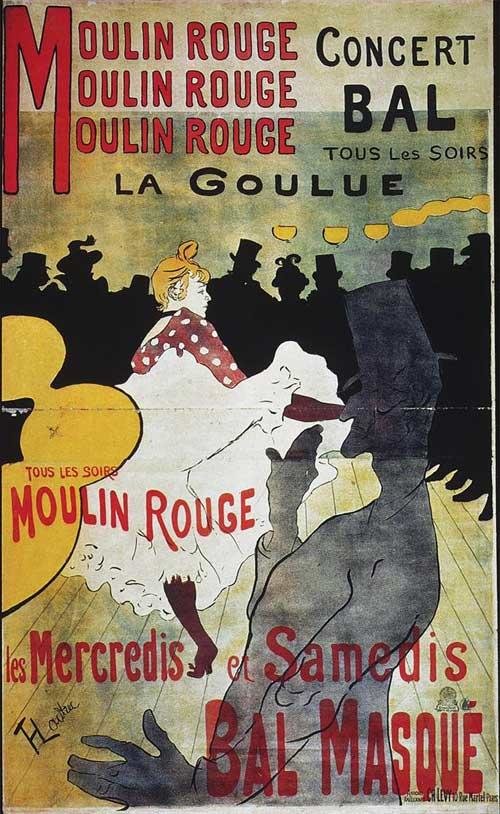

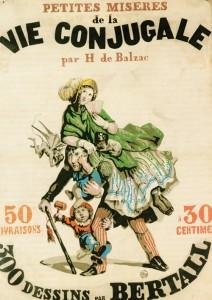

The next step is to place a paper on the inky surface and apply sufficient pressure to ensure that the paper captures the image on the limestone (Drucker & Emily 2009, 12). The artist can repeat this process as many times as s/he wishes, depending on the number of reproductions s/he intends to make. Initially, lithographs were monochromatic and crude, but as time passed, various artists sought to improve the technique resulting in chromolithography, which involved the use of up to twenty different colors on an image.

In 1820, artists discovered that it was far better to use thin metal plates, and they turned to zinc, aluminum, and copper plates. The advantage of using metal was that one could bend it and fit it onto the cylinder of a rotary press for high-speed printing. With the invention of lithography, the limitations of engravings no longer limited artists in the production of their works and so they could produce better-detailed images (Ernst 2005, 56). Later, photolithography saw to the reproduction of photographs, drawings, and illustrations.

Effects of mass-production of lithographs on art

With lithography as a means of mass reproduction, hand produced art dwindled. Most artists focused on satisfying the demand for already existing artwork and forgot about creating original work (Esaki 1957, 79). Even those who still created original pieces were seasonal in their artistry because they would draw a piece and take time off to market and reproduce it, and only draw another when the one they were reproducing stopped selling.

Moreover, the development of lithography resulted in a compromise, in the quality of art. Many artists were in a rush to complete artworks and others sought to replicate either aspects of or the entire lot of their colleagues’ works because these were all readily available (Hawley 1997, 110). Consequently, if an artist’s personal business were not flourishing, he would simply take up another artist’s work and reproduce it for sale (Weitman 1999, 43).

However, not all artists were as greedy or unfocussed. Some of them rallied against the use of this technology in producing artistic work. These artists argued that, mass-reproduced artwork could never take the place of originally produced pieces simply because the mass-reproduced pieces lacked the careful attention and dedication of the artist in working on each piece (Thompson 2004, 25).

Despite the fact that this argument carried weight as illustrated by the relatively cheaper prices of mass reproductions, it neither stopped the middle-class consumer, which was the bulk of the society anyway, from purchasing these pieces for hanging on their walls nor other consumers from using lithographic images in advertising and entertainment (Raimondo 2004, 5). Consequently, business in art flourished.

This, coupled with the fact that even the artists who were against this new technology still profited from the same technology, watered down any effective fire that the arguments may have started. Examples of artists who sought to preserve the sanctity of hand-produced artwork include William Blake, specifically when he produced his Jerusalem painting (Morris 2009, 32), and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, a painter, poet, and illustrator who was a romanticist after the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

Their intention in producing counter-culture artwork was to reform art by rejecting mechanical processes in art production. Dante Rossetti’s The Girlhood of Mary Virgin, 1849 was one such counter-cultural piece whose uniqueness was unrivalled. It was a piece of double artwork comprising of two accompanying sonnets and a comment on the painting (McGann 2009, Para. 3).

Nevertheless, although they waged a valiant war, Blake and Rossetti’s livelihood were dependent on industrialization (Melua 2010, Para. 3). Blake made a living out of commercial commissions while Rossetti was a translator and illustrator of mass produced literature (Lewis 1990, Para. 3). Consequently, theirs was a case of preaching water and drinking wine, and their artists ignored them. However, they had an impact on art in the 19th century to the extent that they preserved originality in artistry by producing their own pieces originally.

Development of Photography

Photography refers to the art of drawing with light (Berry 2010, Para. 3). The photographer uses light to record or capture an object or a scene on a light-sensitive screen or surface (Goldberg 1991, 34). In photography, the camera is an extension of a person’s eye and mind. As a camera, it is simply an object and only becomes a constructive tool that one can use to capture images once a person with the necessary skill wields it (Jeanne 2003, 96).

The concept of photography bears heavily on light control. As early as during Leonardo da Vinci’s time, the principle of camera obscura (Berry 2010, Para. 4), simply translated to mean ‘darkened room’ had grasped the attention of many artists. Initially, artists used a large room with a diminutive hole on one of the walls to serve as the only source of light and consequently set in focus a given image. The resultant image was inverted but exceptionally clear and detailed (Kluver 1997, 40).

The concept evolved into a pinhole camera and reduced in size until artists finally had a portable camera with two mirrors at 45 degrees to produce an upright image. Nevertheless, the images were temporary in nature, and as soon as the object moved or the light shifted, they would fall out of focus. In the early 19th century, Joseph Nicephore Niepce conducted various experiments with lithography and he discovered a method that could permanently capture images in a camera obscura for at least eight hours (Lewis 1990, Para. 4).

This was in 1827 when Niepce recorded the world’s first surviving photograph. Elsewhere, Daguerre had been experimenting with silver iodides to capture images on a light sensitive film. Upon hearing about Niepce’s success, he went over, and they formed a partnership in 1829. Under Niepce’s guidance, Daguerre invented the Daguerreotype, which involved production of images on a chemical surface (Berry 2010, Para. 2).

However, one could only produce a single image at a time, and the procedure was complex (Lunar 2008, Para. 3). Moreover, reproduction through the same process was impossible, and the object had to remain motionless for several minutes before the artist captured its image.

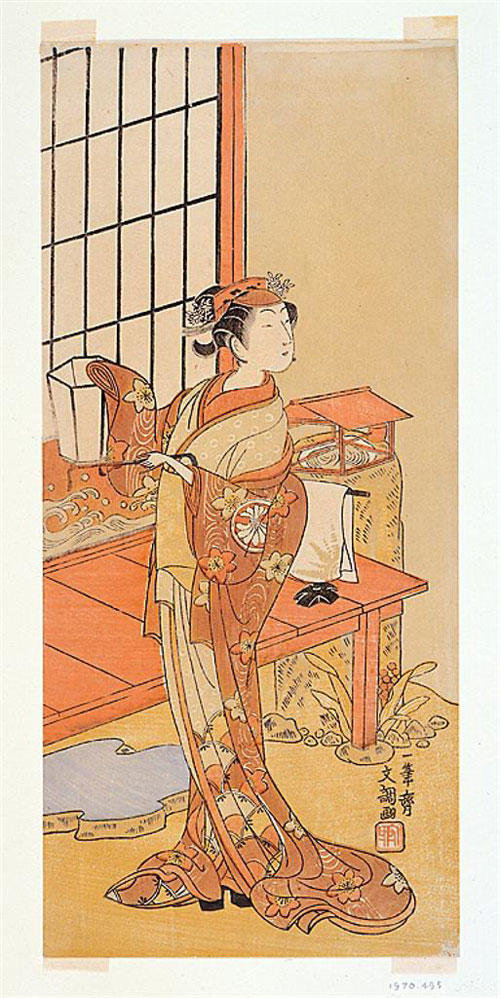

Nevertheless, the resultant images were of high quality with details clearly captured and artists soon adopted this method in the production of portraits. Examples of artists famous for this technique include Albert Sands Southworth and Josiah Johnson Hawes among others (Tucker et al 2003, 23).

William Henry Fox Talbot used different chemicals to come up with a different procedure that had almost similar results in terms of image production, although his images were of a poorer quality (Mercer 2008, Para. 3). However, an artist could use his method to reproduce images and so he had a large following.

Examples of some prominent photography artists include Roger Fenton, who produced the camp scenes of the Crimean war and Matthew Brady and his associates, who reproduced the scenes of the American Civil War. Others are Hine Lewis and Jackson William Henry, a landscape and portrait photographer respectively, who worked as the official photographer for the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories (Berry 2010, Para.3).

Effects of mass reproduced photographic images on art

Initially, many artists rejected the notion of photography as a viable artwork. This is because they focused on the disconnection between the photographer and the camera, which was more technical or mechanical. Consequently, there was disparity in distinguishing the photographer as the artist as opposed to the camera.

To counter this argument, Pierre Bourhan says of the Japanese artist Keiichi Tahara, “Once the eyes and the viewfinder have done their work, Tahara’s hands continue the search. In subsequent elaboration, the artist chooses the support (the glass plate), the dimensions, the form of treatment, the framing, then puts it all together and situates it in space – the installation.

Then and only then, after going through these transitional stages, do we have the work – fulfilled, transcendent, as far removed from reality as a statue or a painting can be” (104-105).

Similarly, Joan Fontcuberta stated of Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dali, Joan Miro, and Antoni Tapies, “in the domain of cameras and photochemistry…photography became a fabulous apparatus for intensifying the gaze and a medium for generating novel experiments. In a word, they showed us once and for all that lens, light and photosensitive materials are merely tools that, like the brush and pigment, further the artist’s work” (Fontcuberto 1995, 9).

Finally, Fontcuberta states of Salvador Dali, “In the same way that automatic writing enabled unforeseen poetic associations to be revealed, so photography provided a way for the Surrealists to fix the unconscious of the gaze. Dali was attracted unusually early on by the transformative capacity of the camera… pictorial interventions on different photos and various collages help us comprehend the powerful influence of the photographic vision” (91).

The results of introducing photography into the 19th century were both positive and negative. For instance, artists could now record realistic images that would ordinarily have taken skilled artists hours or even days to draw within mere seconds (Melua 2010, Para. 2). It was also a powerful means of communication, a mode of visual expression, and a means for the crystallization of memories.

Moreover, photographers’ skill was applicable across the board ranging from astronomy, to medical diagnosis and even industrial quality control. It introduced a technique that could capture details too minute or fast in motion for the naked eye, and could be placed in areas too dangerous for human reach (Meggs 1992, 34).

With all these new and appealing qualities, the public swayed in its loyalty to traditional art. People found photography to me more convenient and cheap as they could use the cameras themselves to capture images without the need for an artist. With time, people adopted photography as a career or as a hobby that kept them occupied (Mazur 1997, 57).

Soon, museums started displaying photography work and critics began to scrutinize various elements of images captured in various fashions. Many forgot about art, and only rich collectors seemed interested in acquiring paintings or drawings. Consequently, the world forgot about traditional artists once more, and this time, it seems as though it will be for good because photography has only progressed since then (Mason 1982, 45).

Nevertheless, if one is being objective about art, then there is no reason to see this as a digression of art rather than a progression because traditional art comprised of images such as portraits of live personages or captures of various sceneries and other features of an artist’s environment (Lewis 1990, Para. 3). Photography is just a faster and more accurate depiction of the same. The only deduction is the artist’s time and labor.

Conclusion

Lithography and photography were new techniques that took the 19th century by a storm. Consequently, different people reacted differently to their integration into the world of art. Nevertheless, they were progressive in their contributions to the art world because the product of photography for instance was the goal of any artist who drew or painted. Images resulting from photography were unflawed, easier and faster to produce.

The artists would undoubtedly feel cheated of the experience of coming up with that image, but in the end, everybody was happier with the quality of photographs. Lithography, on the other hand, was also a means to an end, the end being the mass reproduction of artwork (Meggs 1997, 45).

Due to the industrialization that rocked Europe in the 19th century, more people could afford paintings, although not at the exorbitant prices of original works, but at a standardized price. To satisfy this demand, artists needed a printing technique that was more efficient than hand production, and lithography provided this solution (Tucker et al 2009, 36).

As to whether lithography and photography resulted in a near death of traditional artistry, the answer is affirmative. Nevertheless, if one looks at all this from the perspective of the original intent of art, or the goal of an artist commissioned to draw or paint the portrait of a live subject, photography does not seem lethal to art at all, it seems like a solution to a problem or the artist’s goal.

Appendix of images

Reference List

Acconci, Vito Y. & Acconci Studio. Acts of Architecture at Contemporary Art Museum, Houston 2001: Multi-Bed Series: #1, #2, #3, #5. New York: Collection of Acconci/Acconci Studio, 2004.

Babb, Fred C. Go To Your Studio and Make Stuff: the Fred Babb Poster Book. New York: Workman Publishing Co., Inc., 1998.

Bearden, Romare B. Train Whistle Blues I, 1964: Collection of Laura Groscine, 2003. Web.

Berry, Danielle H. History-What is Photography? Web.

Boone, Gallery G. The Color Explosion: Nineteenth-Century American Lithography. Web.

Close, Chuck M. Self-Portrait/White Ink, 1978; Self-Portrait, 1999; Self-Portrait, 2000; Self-Portrait/Pulp, 2001. Chuck Close Prints: Process and Collaboration. Houston: University of Houston’s Blaffer Gallery, 2005.

Cornell, Joseph V. Custodian (Silent Dedication to MM), 1963.

Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston. Elvis + Marilyn: 2 x Immortal. Houston: University of Houston’s Blaffer Gallery, 1995.

Dali, Salvador E. Baby Map of the World, 1939, Il volto di Mae West. Chicago: The Salvador Dali Art Gallery, 1958.

Dante, Gabriel R. In Daydreams of Conformity. Revolt In the Desert. Web.

DePaoli, Geri A. Essays and artworks created as cultural commentary or homage to the mythic icons of American pop-culture – Elvis Presley and Marilyn Monroe.” In Elvis + Marilyn: 2 x Immortal. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 1994.

Digital Art Practices & Terminology Task Force (DAPTTF). Printmaking Techniques. 2004. Web.

Doisneau, Robert E. Musician in the Rain. Masters of Photography. Masters of Photography. Web.

Drucker, Johanna G., & Emily, McVarnish S. Graphic Design History. In A Critical Guide. New Jersey: Pearson Education, 2009.

Ernst, Max M. The Couple, 1925. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. Imagine That! Activitiies and Adventures in Surrealism. Rotterdam: Word Press, 2005.

Esaki, Reiji F. Collage of Babies, 1893. The History of Japanese Photography. Hokkaido: Hakodate Municipal Library, 1957.

Fontcuberto, Joan W. Experimental photographic work of Picasso, Miro, Dali and Tapies at Primavera Fotografica Biennial Festival, Barcelona. In The Artist and the Photograph. Barcelona: Actar, 1995.

Goldberg, Vicki J. Discussion of emotionally charged iconic photographs describes impact on society, influencing political and sociological behavior. In The Power of Photography: How Photographs Changed Our Lives. New York: Abbeville Publishing Group, 1991.

Hawley, Michael B. Artworks use digital image “tiles” from Internet retried by software program. In Photomosaics: Robert Silvers. New York: Henry Holt and Company, Inc., 1997.

Jeanne, Claude C. Running Fences, 1972-76. Collection of artist. Project for the Charles M. Schulz Museum,. Postcard 4 x 6in.,compare Goldsworthy’s Storm King Wall,1997-98. California: Santa Rosa, 2003.

Kluver, Billy M. One day’s photographs of Picasso and friends at Café de la Rotonde, focusing on Jean Cocteau’s 1916-17 collaboration with Satie and Picasso on the ballet, Parade. In A Day with Picasso: Twenty-four Photographs by Jean Cocteau. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1997.

Lewis, John G. Printed ephemera : the changing uses of type and letterforms in English and American printing. Web.

Lunar, Kelb D. Early Printing Processes. Web.

Mason, Robert G. Photography as a Tool. In Photography introduced as tool of human exploration in science, technology, and aesthetics. Chicago: Time-Life Books, 1982.

Mazur, Thomson J. The Origins ofGraphic Design in America, 1870-1920. Toronto: Yale University Press, 1997.

McGann, Jerome J. Dante Gabriel Rossetti 1849. In The Girlhood of Mary Virgin. Web.

Meggs, Phillip W. A History of Graphic Design. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1992.

Meggs, Phillip W. A History of Graphic Design. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1997.

Melua, Josh L. Printings, Drawings and Photographic Images. Web.

Mercer, Peter K. History of printing. Web.

Morris, William C. Balance Through Art. Web.

Raimondo, Joyce N. Imagine That! Activities and Adventures in Surrealism. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 2004.

Thompson, Jeffery D. Patterns structure brainstorming, creative work, and meditative inspiration. In Creative Mind System. Chicago: The Relaxation Company, 2004.

Tucker, Anne G. et al. The History of Japanese Photography. New Haven: Yale U. P., 2003.

Tucker, Anne G. et al. The History of Japanese Photography. New Haven: Yale U. P., 2009.

Weitman, Wendy D. Printmaking and Pop Art development in catalogue for exhibition at Museum of Modern Art. In Pop Impressions Europe/USA: Prints and Multiples from the Museum of Modern Art. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1999.