Introduction

The electricity industry in Australia is at its peak, after implementing reforms in the 1990s. The reforms pushed the structure of the industry to embrace market factors, although it currently has mechanisms of government interferences with demand and supply forces. This report looks at the composition of electricity generators and their sources of electricity. The industry has particular characteristics of each state and a national outlook too. Electricity generators directly serve the demand for particular states or regions. They establish their generation plants near the demand areas so that there is little need for high voltage transmission. The structure allows Australia to enjoy high distribution efficiency. At the same time, there is less waste of power in the market, as demand automatically matches the supply because the industry regulators relies on a special system for handling offers and requests in the national electricity market.

The report highlights the current policy challenge facing electricity generating companies that rely on renewable energy sources like wind and solar. The country promotes the development of the renewable energy sources of electricity through a special development plan.

However, the plan is yet to become a legally binding policy. The government and opposition parties are debating in parliament about the proposed constitution and the support for the segment as part of the overall electricity industry. The report also looks at the contribution of the industry to the Australian economy. It highlights past improvements and cautions against any regressive policies or trends, as they can affect the country’s economic growth negatively. The report also evaluates the consequences of various policies in the discussion of the industry structure and its role in the country, and then reviews Infigen Energy Limited as a case study.

Analysis of the Current Structure of the Electricity Industry in Australia

Australia initiated market reforms of its electricity industry in the 1990s. The country developed the national competition policy (NCP) to introduce private ownership of electricity production. At the same time, the National Electricity Market took the design of the UK electricity industry model. Notable events in the reform period included the selling of Victoria assets of the statutory authority to the private sector. Other states in Australia followed different reform schedules, such that the entire country had a functioning private sector in the electricity industry by 2003.

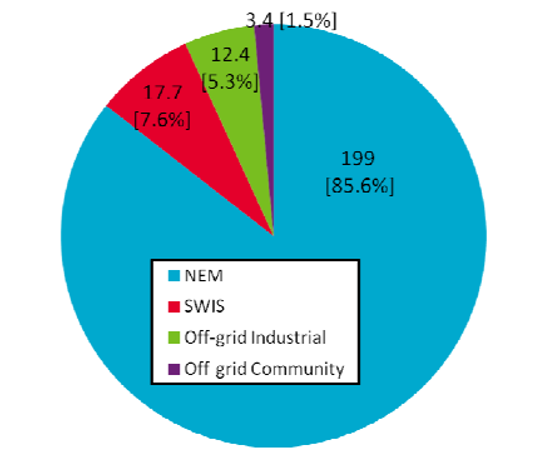

The National Electricity Market (NEM) and South-West Interconnected System (SWIS) are the largest networks of electricity serving the eastern states, South Australia, and West Australia. They cover 95 percent of the market. The remaining 5 percent belongs to off-grid industrial and remote community networks (AEMO 2015).

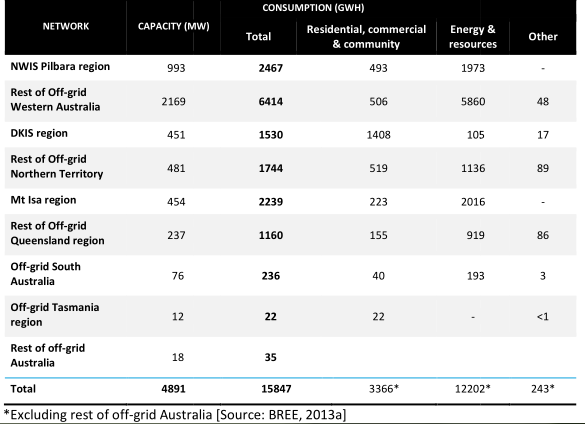

Each Australian region has a network. Western Australian has 40 non-interconnected networks that receive electricity from the state-owned Horizon Power. The North-West Interconnected System (NWIS) is part of the Western Australian network. It is about a tenth in size of the SWIS. The northern territory has Darwin Katherine Interconnected System (Engineers Australia 2013).

The Australian government has policies that intend to boost economic efficiency and development in the energy sector. The policy focus is responsible for a number of reforms geared towards opening up markets in the electricity industry. Each state in Australian has an agreement with the government to implement a national energy market called the Australian Energy Market Agreement presently overseen by the Standing Council of Energy and Resources (SCER). Meanwhile, the Australian Energy Regulator (AER) enforces the rules that come from the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC). The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) manages the eastern states and territories, while the Independent Market Operator (IMO) is responsible for the West Australian electricity market.

In addition to economic efficiency, policies governing the electricity industry aim to improve energy security by ensuring that there is an adequate supply of gas and electricity. In addition, the policies aim to increase safety and customer service. The regulator applies technical safety standards, together with occupational health and safety rules. It also ensures that there is customer protection under the National Energy Customer Framework. Other policy concerns are greenhouse gas emissions management, renewables, and energy efficiency improvement-schemes for solar-feed-in-tariffs.

Every state has a connected transmission and distribution grid. Five regions in the country rely on high voltage interconnections, permitting inter-regional trade up to physical capacity limits. Therefore, different regions have different wholesale prices of electricity. Wholesale trading happens on a spot market. Traders match supply and demand instantaneously and rely on a centrally coordinated dispatch process. The generators of electricity give proposals for electricity supply in intervals of five minutes daily. The bids are won by the generators who qualify, according to the policy set by the AEMO. After making the decision, a particular generator proceeds to enter into production.

The market uses price as a proxy for marginal economic costs to consumers, which arise due to loss of supply. A price cap placed by the NEM rules captures the maximum allowed price of electricity, according to the consumer price index. At the same time, the NEM allows bilateral contracts between electricity generators and consumers, and then moves the balance demand and capacity in the wholesale spot market.

Population and economic growth are key drivers to increase in electricity demand in the NEM. The consumption of electricity declined in absolute terms after 2009-2010. Overall, industrial consumption decreased due to global economic conditions and the high value of the Australian dollar in comparison to foreign currencies. Rising prices of electricity and energy efficiency mandates by the government also led to a reduction in per-capita use of electricity in the residential sector.

Consumption should increase moderately in the coming decade. Population growth in East and South Australia will likely cause gradual stabilisation of residential electricity prices. New liquefied natural gas projects are coming up in Queensland, and they should increase supply to counter the rising demand. Technological advances in the motor industry, which have led to production of electric vehicles, will likely contribute to a significant rise in the demand for electricity. On the other hand, buildings and appliances continue to become energy efficient, which will moderate the increase in electricity demand in residential markets. The use of small-scale solar photovoltaic installations will also reduce the need for a high capacity generation in centralised plants (DEWS 2013).

The cost of electricity includes retail operation costs, network costs, and wholesale electricity costs. Retail cost determination happens after every one to three years, and it includes customer acquisition and retention costs, billing, and meter reading costs. The network costs’ review takes place after five years and considers network revenues as capped by the Australian energy regulator. Wholesale electricity costs change every five years in consideration of prevailing conditions in the NEM. They include price caps, but the provision of spot prices ensures that the caps are less binding (Reserve Bank of Australia 2014).

Up to 10% of the electricity that Australia generates comes from sources that can be replenished. Hydroelectricity contributes more than half of the figure, while the rest comes from solar and wind power sources. Australia promotes investment in renewable sources of electricity generation through a programme called the Renewable Energy Target. Currently, the country depends on coal for the generation of electricity. Only Denmark and Greece surpass it in terms of coal-generated electricity. The situation arises because of vast deposits of the natural resource available in the country and a well-developed coal extraction industry. Growth in total electricity production was most significant from 1990 to 2000. There has been growth from 2000 to the present, but at a lesser degree than in the previous decade.

Australia has a real time balancing mechanism for electricity supply and demand. The system used by the NEM ensures that there is a match at all times. Renewable generators of electricity get a five-minute window to fulfil their obligation before delivery.

Transmission demands for Australia are lower than those of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries. The main power generation centres are near the main load centres and directly fed to the distribution. Thus, the network is more efficient, as it avoids electricity losses associated with long transmission networks. The southern Australia part of the industry has a different grid network from the northern part (World Nuclear Association 2015).

Environmental concerns in the electricity industry are low. The country enjoys a good record in dealing with emissions. The government penalises coal miners and processing companies when they surpass the allowed emission levels of sulphur dioxide. The penalties have compelled coal producers to invest in expensive and efficient equipment to avoid withdrawal of their licenses. The industry produces 33 per cent of the total CO2 emissions in the country through generation. Additional emissions arise out of transmission and distribution activities. Generators use two different types of coal, and each has a different emission level. Generally, brown coal generators produce more CO2 emission than black coal producers. Gas powered electricity generators are also a major source of CO2 emissions (Nelson, Kelley & Orton 2012).

Political influence is a major factor in Australia’s energy policy. Currently, the country is facing a challenge of passing legislation to support the RET scheme. Laws have to pass through parliament, where the government and opposition party members have to debate and vote. The current coalition government faces difficulties in passing laws in parliament because it lacks a clear majority. Other than the two main parties, there are also members who are elected for independent terms and do not have to conform to any party’s positions. The complexity of the political structure of the country is not a major hindrance to the full realisation of the market potential of renewable energy source of electricity.

Effect of the Structure on Strategic Decisions

The resilience of the wholesale market and spot price mechanism to determine the price of electricity presents responsive challenges to consumer prices. Consumers have to wait for generators to evaluate the costs of their investments, and then pass the margins to the wholesale market for consideration by the regulators. The time taken for regulators to evaluate the suitability of a given price proposition with the goals of electricity distribution all over the country ends up affecting the response time. However, the reliance on an automated system ensures that the problems associated with the above reasons are minimal (Brinsmead, Hayward & Graham 2014).

The price caps placed by regulators limit the competition at the retail level. Therefore, firms serving residential and business consumers of electricity cannot initiate programmes that influence their capital resources significantly. They have to consider the available margin of price variation. Their aim is to determine whether it is enough for them to recoup their investment. The price capping policy at the residential level eventually leads to reduced investment in the sector, as companies avoid tying their capital to long periods for getting a return on their investment (Eldring 2009).

Different states and regions in the country have special regulations for their electricity industries. Therefore, companies have to enter into multiple agreements with different state entities to operate in their jurisdictions. The requirements create inefficiencies on a country level and introduce additional costs of implementing company strategic plans. The regulators must consider the expenses that are incurred when distributing electricity in order to enhance efficiency in electricity distribution. However, they review the rates annually or bi-annually. Unfortunately, firms need a more flexible operating environment that allows them to capture opportunities in the short term. In the present situation, firms will have to seek approval or wait for consideration of their business practices by the regulatory authorities before they can implement solutions on a wide scale (Aghdam 2011).

Despite the challenges that the various regulatory arrangements in Australia create for electricity generators and distributors, the market reforms of the 1990s have had a positive influence on the overall competitiveness of the industry. However, not a lot has happened on the demand side of the market. The reforms and present policies seem to influence a reduction in the overall costs of electricity in the country. However, they do not do enough to spur demand (Sehgal 2011).

Customers are encouraged by stable prices or affordable electricity. However, demand quickly recedes when there are unavoidable spikes in prices due to global and local economic factors. Eventually, reduced demand will not influence supply decisions positive. Most distributors will have to consider merging to enjoy economies of scale. Otherwise, new investments into the industry may slow down because of reduced demand (Bryman & Bell 2011). Thus, when looking at the Australian situation from a long-term perspective, there is a need to initiate reforms that will cause demand for electricity to rise beyond the present levels so that there is overall monetary stimulation for private companies to increase investments in distribution and generation. Without such reforms, the present structure will continue limiting active participation and innovation to the basic minimum (AEMC 2012).

Support for renewable energy production through RET will make investments into the sector attractive. However, regulators have to review the price regulation regime affecting the electricity industry’s attractiveness. They have to consider separating renewable sources or compensating renewable energy producers as an incentive for additional investments.

Contribution of the Sector to the Australian Economy

The electricity industry plays an important economic role of providing a key resource for business functionality and general operation of economic activities. The penetration of electricity networks is high in the country, which ensures that consumers can enjoy benefits such as running appliances at home and powering equipment at various institutions. Low prices of electricity are crucial for overall competitiveness of the Australian economy. Goods produced at cheaper production costs end up attracting lower prices or supporting high profit margins. The total cost of electricity in Australia is expected to rise in the future. Households will spend 50 per cent more in 2020 if the current structure persists. However, improvement in the renewable electricity generation segment should translate into lower prices, according to the estimates included in the RET scheme (Clean Energy Council 2014).

Growth in the electricity industry should lead to improvements in investments in the sector. At the same time, there is an increase in employment. Overall, the sector continues to increase consumer incomes through salaries and dividends. It also avails capital for the development of new energy projects by various firms keen on expanding to meet demand needs. The Clean Energy Council (2014) estimates that following the RET scheme will help Australia generate 18,400 new jobs by 2020, which will come from large-scale wind projects and solar projects. There is room to make long-term projections for the industry and the general economy, given the current relative stagnation of electricity demand growth. Stability in demand caused by the industry structure should lead to lower levels of consumer inflation due to energy prices. Reduced inflation promotes long-term business planning and boosts the investment attractiveness of the Australian economy (Narayan & Smyth 2005).

Infigen

Infigen Energy is Australia’s leader in renewable energy electricity generation. The company owns and operates the largest wind farms in Australia. It has a projected total generating capacity of 1600 GWh annually in the long-term. The electricity is sufficient to cover the needs of more than 200,000 Australian homes. The company’s strategy is to increase its investments in solar and wind projects in the country. The currently installed wind power capacity is 556.6 MW, which is distributed in six wind power plants.

Steeply rising electricity prices have been the main motivations for households and businesses’ purchase of solar PV installations. The lifetime of wind farms ran by Infigen is about 25 years, although regulatory authorities specify 30 years as the typical period. At the same time, Infigen models its solar farms to operate for 25 years (Infigen Energy 2014).

SWOT Analysis

Strengths

A high production capacity ensures that the company is able to meet any rise in demand for renewable electricity. At the same time, investments in research and development in its major business in the United State offers the company a repository of solutions to implement in the Australian market. Reliance on power purchase agreements spares the company the challenges of competing directly with its rivals, who are established companies in the electricity generation business. Being a renewable energy producer places the company in favourable terms with environmental and business sustainability policies and concerns supported by different groups in Australia and globally (Infigen Energy 2013).

Weaknesses

The wind and solar power technologies are susceptible to weather changes. In 2014, Infigen Energy had a drop in revenues because of poor wind conditions. The company also has debt exposures that affected its net income (Parkinson 2013). Wind and solar energy generation technologies evolve fast as researchers seek to improve efficiencies and lower the costs of production. However, the company cannot easily write off its existing investments in the present technology when a new and better technology is available in the market. The company can only invest new technology in its new generation plants (Infigen Energy 2014). Therefore, it has to plan before developing or purchasing any technology that has long-term implications.

Opportunities

The company faces a substantial investment opportunity in renewable energy generation and supplies distribution. However, the opportunity remains frozen, until the Australian parliament passes legislation to support the RET scheme (Macdonald-Smith 2015). While facing a threat of boycott to renewable energy by retailers, Infigen Energy also faces opportunities of dealing directly with corporate consumers. However, the scale of the opportunity is low, while the available demand offered by retailers in the NEM is high (Parkinson 2015). Globally, big corporate consumers are opting to fund wind and solar power generation and then enter into long-term generation partnerships with wind and solar power expert companies such as Infigen. The company can also pursue other markets other than Australia, until the present delay in supporting renewable energy policy is over.

If the current RET legislation passes as it is, then there should be numerous opportunities in the industry to cover more than the 32,000 GWh proposed by the Labour Party under the current debate (Elliston, Diesendorf & MacGill 2012). The Labour Party is seeking to increase the allocated electricity generation for renewable energy. It wants wind and solar plants to have a substantial share of the overall electricity production in the country. The need to increase employment and expand the economy is informing the Labour Party’s position in parliament (Maher 2015). The original proposal of RET would have 41,000 GWh of electricity generated, where 4000 GWh comes from rooftop solar installations in homes and business premises around the country (Maher 2015).

Individual states have the power to make legislation affecting electricity generation and distribution; thus, Infigen Energy can lobby specific states for investment opportunities as it awaits the final verdict on the RET scheme.

Threats

The company is vulnerable to any changes that can happen on the RET scheme, which is currently facing an uncertainty about its legislation. Debt repayment schedules are susceptible to changes in interest rates and currency value. A threat by major electricity retailers to withdraw their demand for renewable energy can cause the entire business of Infigen to disappear. The company relies on power purchase agreements and wholesale selling to the retailers. Without retailers, it will only have direct sale agreements that are not easy to achieve for the established plants and consumers (Parkinson 2015).

Failure to pass the appropriate RET legislation will promote the current situation in the market. It is easier for coal plants coming up near residential markets than wind farms. The current legislation wanted to improve electricity generation, but it did not take into consideration environmental concerns at the time of enactment (Whitlock 2015).

Porter’s Five Competitive Forces Analysis

Power of buyers

Renewable energy power producers rely on electricity retailers to advance their generated electricity to consumers. The arrangement happens through the NEM, which operates an automatic target match of demand and supply. Specified market forces, such as the prevailing inflation rates and disposable incomes of residential consumers, determine the prices. The government places caps on wholesale prices. At the same time, retailers also affect prices by quoting bids during every review process by the market. The arrangement gives the sellers and buyers equal rights in determining prices. However, retailers can also decide their choice of power sources. It is possible for retailers to boycott power from particular sources, but it is impossible for them to affect the ceiling price adversely.

Power of sellers

Electricity generators relying on wind and solar power sources are few in Australia. They also satisfy specific market needs provided by power-purchase agreements. The extra capacity sold to the national electricity market is low, while the power offered by non-renewable energy suppliers is very high. Renewable energy producers rely on equipment manufacturers, while some of them have vertical integration systems with the equipment manufacturers. Therefore, they face a few threats from the suppliers (Stringham 2012). They also rely on long-term supply contracts, which enable them to enjoy stable prices for their capital investments into power production plants.

Threat of new entrants

New entrants have to invest in their own production plants. They have to seek licenses from the states and the national government. They may also have to comply with various regulations on the location and operation of power plants. Eventually, they are able to trade their electricity in the whole market. However, there are no special preferences or treatments for small or new renewable energy producers of electricity. As they enter the market, they face a challenge of coping with rivals like Infigen Energy, who own considerable investments and have ongoing power purchase agreements with particular institutions and state governments. Based on the above facts, new entrants pose no major threat for the established operators in the renewable energy, electricity segment.

Threat of substitutes

There is no distinction between the price of renewable energy and non-renewable energy in the national wholesale electricity market. Companies compete against each other, irrespective of their energy sources. However, different companies incur a variety of costs in the production methods. The costs influence the ability of companies to sell their electricity at low prices. The substitutes for wind and solar electricity sources are coal and gas sources. The threat of the substitutes is very high. The current laws support increased investment in coal and gas-powered generating plants. At the same time, these sources offer cheaper electricity by having low costs of production compared to renewable energy. Only hydroelectricity may be cheaper than coal. However, the generation capacity of hydroelectricity in Australia is very low. Therefore, the major threats for renewable power producers are oil and gas powered plants.

Existing industry rivalry

The present rivalry is high because companies seek to enhance their efficiency and improve their profitability. Most of the companies acting in the industry seek to keep costs low and remain profitable. Very few are considering substantial investments in electricity generation because of the slowing growth in electricity demand. Innovation in the industry is not very high. Most coal producers concentrate on management and incremental technology changes to achieve a competitive advantage. The industry is in its maturity stages and companies have little room to manoeuvre. The cap on wholesale pricing of electricity also limits the range of innovations that companies can contemplate and implement. There is competition for contracts with institutions or state governments for wind and solar electricity producers. However, for the actual product, there is little room for strategic moves as all prices are regulated in the market.

Conclusion

The electricity industry in Australia grew rapidly in the 1990s, but it slowed down after 2010. Analysts believe the country has reached its peak consumer demand. The possibilities of an improved consumption demand exist in the renewable energy segment of the industry. However, as this report illustrates, there are legislative hurdles that the country has to overcome before realising a second transformation of the industry. Moreover, the current market orientation has allowed the country to improve its competitive advantage. Reforms led to improved efficiencies for the main producers and distributors. They also led to the proper structuring of plans and distribution networks to limit losses and improve penetration. However, the current structure is limiting additional investments as companies continue to face increased costs, but cannot increase prices without approval by the regulator. The country needs to review its policies to allow additional room for market-based pricing in the industry.

Reflection

Reforms are good and can stimulate industry growth. However, as the report illustrates, they are only good when the circumstances causing the reforms are supportive. Currently, the Australian electricity industry is stagnating because the policy changes are not happening as fast as they should. The lesson here is that regulators must be in touch with the realities and promote rapid enactment of the relevant legislation to improve current policies and support new policies. If I am in a regulatory job position, where I have to deal with industry stakeholder and contemplate reforms, I must first study the industry and then evaluate its prospects for growth with the current policy before considering a new policy. In this report, the approach was similar, and it matches the learning outcomes of the module.

It provides a background of a real industry in the world and relies on a number of sources for information. The course was intended for students to learn proper ways of researching economic and business concepts. The report preparation task was a practical lesson for understanding business and economics concepts. It provided a wide scope of analysis that would present macro and micro economic elements to discuss. At the same time, the inclusion of the company analysis part of the report presented an avenue for using business tools such as the SWOT analysis. These tools allowed me to understand the context of strategic decisions that a company makes. They also presented a company-specific outlook of the industry. Therefore, I am able to form a comprehensive picture of the Australian electricity industry and place myself at any capacity. I know the issues that affect my position as a regulator and those that affect my position as a company head.

I am also able to keep up with the current economic events and relate them to theories and best practices of economics at the macro and micro levels. For example, I understand the reasons why there would be a slump in electricity generation investments when the Australian parliament votes to reject the RET scheme proposal. The report has been instrumental in improving my critical thinking capabilities. I am now able to appreciate and interpret quantitative data and use it to make inferences on related factors or the effects on an economy. When faced with real-world problems, I can employ the knowledge gathered from the report and presentation to find solutions.

Although the current structure of the Australian electricity industry is not optimal, it exists in its current formation because of a number of factors caused by different stakeholders. Understanding the interconnection of various causes and effects of economic changes was an outcome of preparing the report. For example, I can match the proposed increase in employment opportunities caused by the legislation of the RET scheme, with growth in the Australian economy as employees increase their consumption of goods and services. The task was helpful in bridging gaps between theory and practical understanding.

With the new knowledge and skills, I should be able to handle future job demands of analysing industries and making recommendations based on findings and underlying economic conditions. As an international student, I was impressed by the differences in political and economic circumstances affecting companies. At the same time, I recognise globalisation factors at play even at the local levels. For example, in the Australian case, I realised that the demands for cleaner energy and reduced emissions are due to global forces against climate change. Although interventions are localised, such as taxation, their inspiration is global.

At the same time, the support offered by the electricity industry to the overall competitiveness of the Australian economy was notable. It highlighted the need for a country’s industrial policy to match its internal and external economic circumstances. In retrospect, focus on only the internal needs of the country would not have allowed it to achieve the same success through liberalisation. The country might have preferred to stick with state producers of electricity and end up promoting monopolistic practices that impede growth and innovation.

Overall, I have become better at interpreting economic trends and adapting to a given strategic response at a company or country level. I have been able to use my knowledge of business management and economics to solve a real world problem in a way that is helpful for someone who may have the same skills or not. Thus, I can serve as a consultant or advisor to institutions that are interested in venturing into a particular sector of any economy in the world. The skills will allow me to have a better job outlook in my home country. I am able to combine the research task experience and the experience of studying in a foreign nation, where I interact with systems and policies that are different or similar to those of my home country.

I have gained a lot in the course and the assignment, such that I can develop a globalised outlook of business positioning and customise business solutions to local levels. Working in an international business environment and witnessing different business cultures of the world as I do research will continue to improve my understanding of the current course outlines, related subjects, and their importance to my career development. I look forward to future research assignments as an actual expert in economics and business, where I will be able to contribute to the market value of the companies I work for as an employee or consultant. At the same time, the knowledge gained will be instrumental when I am advising business owners about handling the opportunities created by shifts in government policies and avoiding business threats.

In the end, I can now determine the appropriate strategies that a business should pursue in any industry. I can look at the market structure using relevant business tools and align findings with the existing conditions and resources in the business and its market. The information captured by a comprehensive research like this one will then allow me to make an informed conclusion that has market value.

Reference List

AEMC 2012, Power of choice review – giving consumers options in the way they use electricity, Australian Energy Market Commision, Sydney. Web.

AEMO 2015, AEMO National electricity market (NEM). Web.

Aghdam, RF 2011, ‘Dynamics of productivity change in the Australian electricity industry: Assessing the impacts of electricity reform’, Energy Policy, vol 39, no. 6, pp. 3281-3295. Web.

Australian Energy Regulator 2014, Industry information. Web.

Brinsmead, TS, Hayward, J & Graham, P 2014, Australian Electricity Market Analysis report to 2020 and 20130, Report No. EP141067, CSIRO. Web.

Bryman, A & Bell, E 2011, Business Research Methods, 3rd edn, Oxford University Press. Web.

Clean Energy Council 2014, Renewable energy target. Web.

DEWS 2013, ‘The 30-year electricity energy’, Discussion Paper, Department of Energy and Water Supply, City East. Web.

Eldring, J 2009, Porter’s (1980) generic strategies, performance and risk, Verlag GmbH, Hamburg. Web.

Elliston, B, Diesendorf, M & MacGill, I 2012, ‘Simulations of scenarios with 100% renewable electricity in the Australian National Electricity Market’, Energy Policy, vol 45, pp. 603-613. Web.

Engineers Australia 2013, Energy. Web.

Infigen Energy 2013, ‘Capital East solar farm update’, Community Newsletter, 2013, p. 1. Web.

Infigen Energy 2014, Let the renewables season begin. Web.

Infigen Energy 2014, Our business. Web.

Macdonald-Smith, A 2015, Infigen Energy climbs back into black. Web.

Maher, S 2015, Renewable energy target: Macfarlane offers wind farm deal. Web.

Narayan, PK & Smyth, R 2005, ‘Electricity consumption, employment and real income in Australia evidence from multivariate Granger causality tests’, Energy Policy, vol 33, no. 9, pp. 1109-1116. Web.

Nelson, T, Kelley, S & Orton, F 2012, ‘A literature review of economic studies on carbon pricing and Australian wholesale electricity markets’, Energy Policy, vol 49, pp. 217-224. Web.

Parkinson, G 2013, Infigen Energy switches on solar as it plans a new power play. Web.

Parkinson, G 2015, Infigen calls bluff on utility threats to ‘boycott’ wind, solar. Web.

Reserve Bank of Australia 2014, How are electricity prices set in Australia?. Web.

Sehgal, V 2011, Supply chain as strategic asset: The key to reaching business goals, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ. Web.

Stringham, S 2012, Strategic leadership and strategic management: Leading and managing change, iUniverse, Bloomington, IN. Web.

Whitlock, R 2015, Australian state of Victoria open for wind energy business. Web.

World Nuclear Association 2015, Australian electricity. Web.