Introduction

War photography is a specific direction of photojournalism, and it can justly be recognized as a rather ambiguous activity. Armed conflicts are the culmination of the most severe and sometimes irresolvable political contradictions. During such events, conditions are created for the manipulation of public consciousness through propaganda that can be quite crude and primitive. Sometimes, war photography is one of the tools that is used for the purpose of propaganda. In addition, because of an increased risk of taking photos under combat conditions, such pictures are highly valued, and the salary of military photojournalists is quite high. In this regard, such work is frequently criticized since moral and ethical aspects are affected in this case. Due to the existence of such delicate aspects, the study of the war photography phenomenon is rather relevant and necessary. The purpose of this report is to identify basic trends in the development of war photography and determine the conceptual, stylistic, and technical changes observed in the course of its formation.

Main Features of War Photography

The object of war photography is everything that is connected with the course and dynamics of the armed conflict. It forms the viewer’s perception of the nature of what is happening. In other words, the photo can show both direct combat actions and what relates to them, for example, operations in hospitals. Despite the fact that photojournalists do not take an active part in hostilities, they also face certain danger and quite often experience psychological pressure. Nevertheless, the danger of stress is not as unique as real physical threats are also present. A striking example is the situation of Hilda Clayton, an American military photojournalist who shot military training in Afghanistan and was the victim of an explosion, capturing it at the last moments of her life (see fig. 1). Such a tragedy can happen to those specialists who conduct their work in “hot spots” and expose themselves to an intentional risk.

As it can be seen from the example, the most significant feature of war photography is that specialists are most often work in the epicenter of danger; in this regard, they expose their lives to significant risk on an equal basis with other participants in the events reflected. Moreover, their activities are extremely complicated technically. Photographers have to possess quite much professional equipment and at the same time be mobile in order to move urgently to different points.

Also, war photography is closely associated with various moral and ethical contradictions, which makes the work of photojournalists even more difficult. For example, according to McMaster, a professional approach and the corresponding ethics require the ability to abstract from a particular situation (191). It is essential to remain neutral to everything that happens on the battlefield or nearby and at the same time closely monitor any events. Thus, war photography is the direction of photojournalism, the main features of which relate to the immediate working conditions of the photographer and specific aspects resulting from them, namely stress, a risk to life, and the difficulty of equipment transporting.

Emergence and Development of War Photography

After such a phenomenon as photography was invented in the 1830s, the possibility of shooting military events was first considered. The primary goal was to raise public awareness about everything that was happening as photos could help to make a complete impression and

opinion than the newspaper texts or official bulletins. Nevertheless, the technical imperfection of the early photographic equipment made it impossible to recreate the pictures of rapid actions when shooting motion. That is why photographers of that time reflected the course of military operations not fully, shooting such static objects as fortifications, standing soldiers or officers, and territories before and after battles. The first pictures relating to war photography can be considered a number of daguerreotypes that were connected with the events of the American-Mexican war; they were made in 1847, the name of the photographer was not fixed, and their authorship cannot be established (McLaughlin 43). However, some historians believe that one of the first military photographers, whose name is known today, was John McCosh, a surgeon of the British Bengal army (McLaughlin 47). He photographed colleagues, weapons, architecture during the events of the second Anglo-Burmese war (see figure 2).

The importance that the technical development of photographic equipment acquired during the wars of the early twentieth century emphasizes a close relationship between war and photography not only in an exclusively journalistic sense. It can be assumed that during this period, photographic technology received the official status of a military instrument. As Borchard et al. remarks, a technical side of the process is extremely important: in the mid-twenties of the twentieth century, the production of new photographic equipment was established in Germany (78). They were compact cameras with almost perfect optics, especially for that period, and they radically expanded the possibilities of shooting. Thus, photographers were able to shoot certain objects from any angle with different perspective and distortion, and they could do it almost imperceptibly for others under adverse conditions. This technique became widespread on the battlefields and was the prototype of many modern professional cameras.

Use of Photographic Technique in the Period of the Most Significant Wars

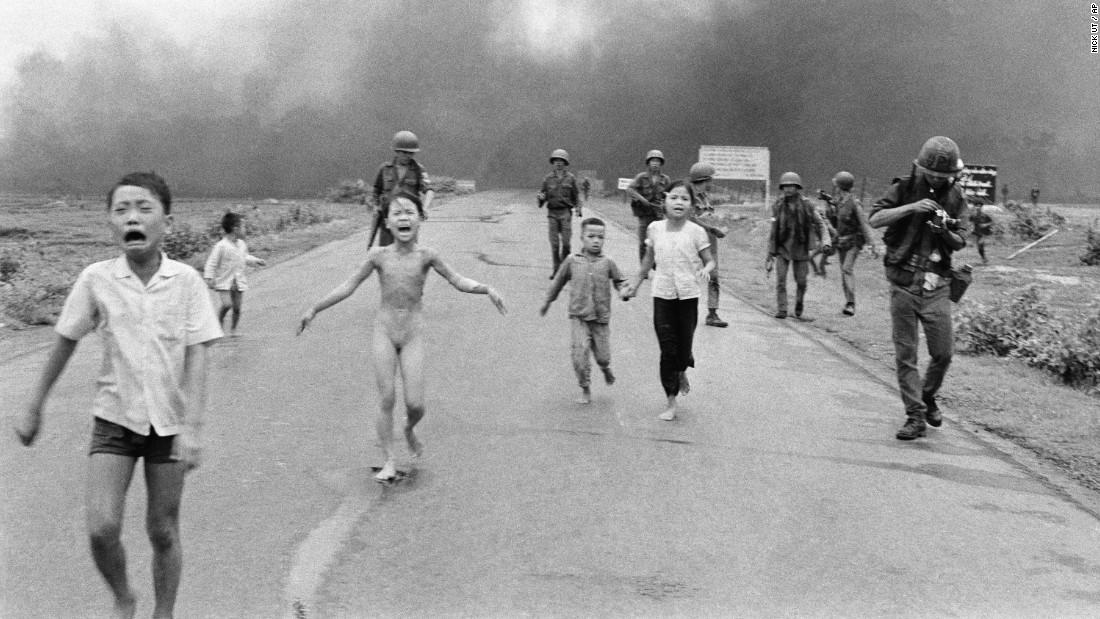

Due to the development of photography technologies, society could see many events that would have gone unnoticed if it had not been for professional cameras. Many significant moments were discussed mainly due to the activities of photographers who managed to be present in the most important places and record significant events. For example, the Nuremberg trial after the Second World War can also be considered the sphere of activity of war photographers since its defendants were directly related to military crimes (Oldfield and Allbeson 92). Also, numerous scenes during that war helped the whole world to learn about those terrible events that were happening in the battlefields and formed an approximately accurate picture of those actions. The war in Vietnam, as Möller notes, was an era when photography was developed quite well (269). Correspondents of that time actively withdrew hostilities, and many photographs showed tragic events, not hiding the realities of the war (see figure 3). A special technique became more sophisticated than earlier, and specialists did not have to carry such large and heavy equipment as one century before. Due to the improvement of technologies, the development process became more rapid, and the quality of photos noticeably changed for the better. All these innovations made it possible to provide a significant breakthrough in the field of war photography, and the display of all the recorded events became as realistic as possible.

Thus, the popularity and success of such a direction as war photography were hardly disputed by those who witnessed pictures taken by experienced and professional experts. In addition to displaying necessary events and materials that occurred during military conflicts, photographers managed to draw public attention to certain issues and thereby create a resonance around this or that problem. That is why photos directly from battlefields are often considered a rather successful propaganda tool.

War Photography at the Present Stage

Today, various international conventions provide for strict punishment for attacking journalists and photographers. However, as practice shows, they are often targeted by militant groups (McLaughlin 75). Sometimes, it happens to express hatred for photographers’ opponents or prevent the facts that are displayed in specific pictures from being disclosed. When terrorism became a part of armed conflicts, war photography turned into a more dangerous phenomenon as some terrorists started to target journalists and photographers. During the war in Iraq between 2003 and 2009, thirty-six photographers and their colleagues were kidnapped or killed (Luckhurst 359). From a comparison of different branches of photojournalism, it is evident that war photographers most of all risk their lives and mental health. At the same time, the coverage of news from war zones is more prosperous than any other branch of journalism. In wartime, the time of newspaper sales usually increases.

Nevertheless, a few conflicts in the world receive significantly wide attention, and its merit is primarily due to quality images.

In addition to such well-known wars as the conflicts between Israel and Gaza, the war in Iraq and the fight against drug traffickers in Mexico, most civil wars and armed conflicts in developing countries pass unnoticed and are barely covered by the media. The fundamental reason is that the press is often not interested in covering such events because these countries are unfamiliar to the public. Regions are either far away or have no political and economic significance for the developed states of the world. Also, they lack infrastructure, which makes communication more difficult and expensive. Moreover, such conflicts in remote areas are much more dangerous for war correspondents. Therefore, not all military actions are covered in the press.

Embedded Photojournalists

The twenty-first century introduced new risks into the life and professional practice of war photographers and also formed new links between them and the official authorities. In the early 2000s, the notion of embedded journalists first appeared, and war photojournalists were also included in this category. This term refers to correspondents who are attached to military formations participating in armed conflicts. However, as McMaster notes, the practice of embedding journalists, including photographers, to the active forces is often criticized (194). It can be regarded as a part of an advocacy campaign and the desire to divide journalists and civilians in order to make the latter sympathize with the forces that invade. Nevertheless, despite some contradictions related to the profession, it remains relevant and in demand.

Gender Aspect of War Photography

It is rather evident that the analysis of the development of war photography at the present stage cannot bypass such an aspect as gender. The activity of those women-photojournalists who work in the conditions of armed conflicts undoubtedly has its specifics. The analysis of the reasons why women decide to go on dangerous business trips to war zones deserves particular attention. Perhaps, it can be explained by the attempt to be useful to society and carry out important work, as well as the desire to prove that even such a dangerous profession is also suitable for women.

As for the psychological aspect of women’s work as photographers in “hot spots,” it is possible to assume that the experience of any person’s death and the sense of constant tension have a greater influence on them than on more men. One of the key points that deserve discussion is gender discrimination and its possible manifestations. Thus, according to Callister, when working in “hot spots,” women can face two types of discrimination:

harassment by militants and the negative attitudes of civilians (114). However, such cases are purely individual and cannot be regarded as a pattern.

Also, it is likely that after returning home, women will experience more pronounced symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder than men. According to Zarzycka, when returning from “hot spots,” some women feel the reluctance to communicate with others, feel depressed, and suffer from alienation to current events. It is quite natural, especially when it is about serious armed conflicts with a large number of victims. Therefore, the profession of a woman-photojournalist is associated with not less risk than a similar male position.

Theoretical Perspectives of the Development of War Photography

According to the fact that the process of developing technologies in the sphere of creating equipment for professional photography is not standing still, it is likely that new samples of high-quality equipment will regularly appear. Accordingly, war photographers will be able to make even more detailed pictures from their workplaces. Certainly, today, there are quite a few ways to avoid human involvement, for example, the use of quadcopters or any other unmanned aerial vehicles that are capable of taking photos and video at a distance. However, the images made by people are more emotional and vivid since the human factor often plays a significant role.

At the same time, the number of war correspondents can be increased as more and more people are interested in news, and various media platforms continually search for additional resources of high-quality content. The more viewers see this or that reportage, the greater the chances that a public resonance will be formed, which, in its turn, may be beneficial to some representatives of the authorities. In the decision-making process, it is essential to adhere to a maximally objective position and adequately assess all the information that comes from the press. It is important to remember that wars are, first of all, tragic events, and only then places for reporting.

Conclusion

Thus, the history of the formation of war photography has undergone significant changes during the existence of this work. Regular improvement of technologies in this sphere allowed achieving the maximum quality of pictures. Due to many outstanding personalities, the theme of war photography received a rather wide public distribution. A gender aspect can be considered quite relevant when it is such a profession. Prospects for the development of this area largely depend on how quickly technologies will develop and whether people continue to use people as a source of obtaining high-quality photographs.

Works Cited

Borchard, Gregory A., et al. “From Realism to Reality: The Advent of War Photography.” Journalism & Communication Monographs, vol. 15, no. 2, 2013, pp. 66-107.

“British; Royal Artiller at Toungoo, Burma.” CitiesTips, 2017. Web.

Callister, Sandy. The Face of War: New Zealand’s Great War Photography. Auckland University Press, 2013.

CNN Library. “South Vietnamese Forces Follow after Terrified Children after a Napalm Attack on Suspected Viet Cong Hiding.” CNN. 2017. Web.

Fichtl, Marcus. “Hilda Clayton’s Final Moments Before Fatal Blast.” Stars and Stripes, 2017. Web.

Luckhurst, Roger. “Iraq War Body Counts: Reportage, Photography, and Fiction.” MFS Modern Fiction Studies, vol. 63, no. 2, 2017, pp. 355-372.

McLaughlin, Greg. The War Correspondent. 2nd ed., Pluto Press, 2016.

McMaster, Herbert R. “Photography at War.” Survival, vol. 56, no. 2, 2014, pp. 187-198.

Mohammed, Eman. “Why Would a Woman Cover War?”Witness, Medium, 2017. Web.

Möller, Frank. “Witnessing Violence Through Photography.” Global Discourse, vol. 7, no. 2-3, 2017, pp. 264-281.

Oldfield, Pippa, and Tom Allbeson. “The Business of War Photography, from the Second World War to the Cold War.” Journal of War & Culture Studies, vol. 9, no. 2, 2016, pp. 91-93.

Zarzycka, Marta. Gendered Tropes in War Photography: Mothers, Mourners, Soldiers. Routledge, 2016.