Introduction

During the 1970s, the U.S. military academies participated in one of the largest changes that helped to recast the role of women in the American military. In 1975, President Gerald R. Ford signed Public Law 94-106, which authorized admission of women to the Army, Navy, and Air Force (Devilbiss, 1990), and, in the following year, the first class of women entered these service academies (Colaw, 1996).

Now, more than 20 years later, over 6,000 women have graduated and received commissions from the military academies. Although senior officers at the military academies indicate that their institutions have attempted to create an environment where leadership by both female and male students is encouraged and recognized, traditional military leadership models have been male-oriented and have posed challenges for women in the military (Versaw, 1997; Youngman, 2001). Military responsibilities are often perceived as contrary to societal expectations about appropriate roles for women (Arkins & Dobrofsky, 1978; Eagly, Karau, & Makhijani, 1995; Versaw, 1997).

The purpose of this study is to examine perceptions among military academy students regarding gender roles associated with military leadership positions. An understanding of current perceptions among military academy students regarding the relationship between gender and leadership success characteristics is critical for the success of continued initiatives geared toward gender integration and leadership development at military academies and other male-dominated organizations.

Gender Stereotyping

Gender stereotyping has been defined as “the belief that a set of traits and abilities is more likely to be found among one sex than the other” (Schein, 1978, p. 259). This tendency to attribute characteristics to gender can be extended to occupations that are more likely to be held by primarily men or women (Eagly & Johnson, 1990; Norris & Wylie, 1995). For example, the military has traditionally been regarded as a masculine occupation (Arkins & Dobrofsky, 1978; Youngman, 2001); thus, military leaders, when selecting or promoting other soldiers to be leaders, may look for personal attributes thought to be more characteristic of men than of women.

More men than women may be perceived as having leadership potential and thus be given more opportunities to exhibit leadership. These perceptual dynamics may then strengthen stereotypes that women are less qualified than men for military leadership positions, and this can have far-reaching implications for recruitment, selection, placement, evaluations, and promotions, as well as for military readiness and performance (Norris & Wylie, 1995; Youngman, 2001).

Over the past two decades there has been much research on gender stereotyping. Early studies, which focused on the differences in perceived stereotypical expectations of women and men, generally indicated that men are perceived as better suited than women for leadership roles (Nieva & Gutek, 1981). For example, a classic early survey conducted by Bowman, Worthy, and Greyser (1965, p. 28) indicated that women were perceived to be “temperamentally unfit” for managerial positions.

Bass, Krusell, and Alexander (1971) also reported similar negative perceptions, whereas early studies conducted by Broverman and colleagues (Broverman, Broverman, Clarkson, Rosenkrantz, & Vogel, 1970; Broverman, Vogel, Broverman, Clarkson, & Rosenkrantz, 1972) identified traits predominantly attributed to men as more positive, such as competency and rationality. Traits attributed to women were less positive and tended to be restricted to affective characteristics such as warmth and expressiveness. Other studies, such as those conducted by Rosen and Jerdee (1973, 1974a, 1974b) and Bartol and Butterfield (1976), showed that gender stereotypes were related to expectations regarding the appropriateness of specific supervisory behaviors, which could influence supervisory performance evaluations and personnel decisions.

Job-Relevant Stereotypes

Whereas the above studies investigated the general nature of gender role stereotypes, early research by Schein (1973, 1975) concerned the relationship between gender role stereotypes and perceptions of effective management characteristics. Schein (1973) initially investigated managers’ perceptions of the relationship between gender stereotypes and characteristics perceived as required by successful managers.

Specifically, 300 male middle managers rated women, men, or successful middle managers on the Schein Descriptive Index, a 92-item scale that elicits perceptions of gender role stereotypes. It was found that successful middle managers were perceived to possess characteristics, attitudes, and temperaments more commonly ascribed to men than to women. There were significant similarities between ratings of men and successful managers, whereas there was little resemblance in attributes assigned to women and successful managers.

An analogous study of female middle managers suggested that they held similar perceptions of a male managerial model (Schein, 1975). Female managers accepted stereotypical masculine characteristics as a model for success in management implying that female managers in the study were as likely as male managers in the previous study to make selection, promotion, and placement decisions in favor of men (Schein, 1975).

In a later replication of these earlier studies, Brenner, Tomkiewicz, and Schein (1989) found that male middle managers adhered to a masculine managerial stereotype in their perceptions of managerial success. However, female middle managers in the study rated successful middle managers as having both masculine and feminine characteristics and attributes, which indicates that female middle managers held more expanded gender role perceptions of managerial success.

Additional recent studies of undergraduate and graduate students (Dodge, Gilroy, & Fenzel, 1995; Norris & Wylie, 1995; Schein, Mueller, & Jacobson, 1989) have shown similar patterns. Dodge et al. (1995) and Schein et al. (1989) reported that female management students did not gender-type the managerial job, but male management students characterized the successful manager with stereotypically masculine traits. Norris and Wylie (1995), who used the Personal Attributes Questionnaire instead of Schein’s Descriptive Index, also found that male college students stereotyped the successful managers in masculine terms but women students did not.

Role Congruity Theory

Role congruity theory offers an explanation for the gender stereotyping of leadership positions by maintaining that perceived gender roles may conflict with expectations regarding leadership roles, especially when an occupation is held predominantly by one sex (Eagly et al., 1995). Meta-analyses of gender effects in the evaluation and effectiveness of leaders indicate support for role congruity explanations.

In the analyses of 61 empirical studies, it was found that women leaders tended to be devalued to a greater extent when they held leadership positions in male-dominated areas or fields and when they exhibited stereotypically masculine leadership styles, such as autocratic or directive styles (Eagly, Makhijani, & Klonsky, 1992).

Academy Cadet Gender Role Stereotypes

The primary purpose of this study was to determine the extent to which associations between gender role stereotypes and requisite leadership characteristics exist among military officer candidates at the United States Air Force Academy (USAFA) and to compare the outcomes to the previous studies conducted by Schein (1973, 1975) and Schein et al. (1989). The Academy population is unique, in that the mission of USAFA is specifically focused on developing leaders by exposing cadets to extensive leadership training and providing opportunities and experiences in a variety of leadership challenges.

Despite the efforts by the institution to expose cadets to a variety of leadership models and despite recent research results (Norris & Wylie, 1995; Schein et al., 1989) that suggest that current college students may hold less gender-specific managerial stereotypes than students three decades ago, cadets at USAFA are expected to hold gender role stereotypes. Several factors weighted the hypotheses toward mirroring Schein’s early results as opposed to her more recent findings. These factors include the masculine tradition of the military and its academies, the nature of applicants who apply to military institutions, and research that specifically assessed gender stereotypes in military populations (Boldry, Wood, & Kashy, 2001).

Foremost, the military is still considered a masculine occupation. With less than 16% of the entire military officer corps composed of women and even less, slightly over 13%, of the service academies composed of women (Manning & Wright, 2000), some argue that “the military is the most male dominated of all social institutions” (Johnson, 1997, pp. 3-4). Because there are few women at the service academies, there are also few cadet women leaders as role models. The traditions associated with service academies are traditions associated with men, such as short hair and performing push-ups as punishment. In addition, cadets within the academies receive less exposure to the world outside their academy than do civilian college students.

Thus, cadets are strongly steeped in the attitudes, norms, and traditions within the academy walls during their 4 years at the academy. Recent research with military college trainees by Boldry et al. (2001) demonstrated that both male and female military trainees evaluated women as less suitable for military work. The college military trainees in the study perceived that men, more than women, possessed the motivation and leadership skills necessary for effective military performance. The authors concluded that gender stereotypes most likely accounted for the evaluative differences because the men and women in the study did not differ on objective performance indices.

The combination of the strong male-dominated population, the traditions associated with service academies, and recent research showing gender bias among both male and female military trainees suggest that cadets’ perceptions of gender stereotypes may be more pronounced than those of their civilian college student counterparts. Thus, the first hypothesis was as follows:

- Hypothesis 1: Male and female cadets will perceive successful officers as possessing attitudes, characteristics, and temperaments more commonly ascribed to men in general than to women in general.

Work Experience With Women Leaders and Gender Role Stereotypes

Bowman et al. (1965) found that men and women who reported actual experience working with women managers were more likely than those without such experience to be favorable toward women in managerial positions. Further, results of studies by Baron (1984) and Heilman, Block, Simon, and Martell (1989) suggested that employees’ gender role stereotypes about female managers vanished after employees worked for them.

Powell’s extensive review of subordinates’ responses to managers (Powel, 1990), as well as research and reviews by Eagly and associates (Eagly, 1987; Karau & Eagly, 1999), corroborates these earlier findings. Laboratory studies indicate that once subordinates have worked for both female and male managers, the effects of stereotypes disappear, and managers are treated as individuals rather than as representatives of their sex (Powell, 1990). In alignment with these research findings, it is expected that cadets with more exposure to female cadet commanders will have a less masculine gender role stereotype of successful officers than will cadets who have had less exposure to female commanders. Thus, the following hypothesis was advanced:

- Hypothesis 2: Cadets with more exposure to female commanders will perceive successful officers as possessing attitudes, characteristics, and temperaments more commonly ascribed to both men and women than will cadets with less exposure.

Successful Performance and Gender Role Stereotypes

Research studies on gender and leadership effectiveness generally reveal equal effectiveness of male and female leaders in the aggregate, when generalized across a variety of studies in a variety of settings. However, consistent with role congruity theory, leadership behaviors exhibited by male and female leaders may differ and may be evaluated differently depending on the extent to which the particular role is defined in masculine terms (Eagly et al., 1995; Thompson, 2000).

Women in male-dominated areas or fields tend to be seen as less effective than their male counterparts. Likewise women may be evaluated negatively when they violate gender role expectations by failing to exhibit consideration or affective leadership behaviors, whereas there may be less expectation that male managers will exhibit these types of leadership behaviors (Dobbins & Platz, 1986; Eagly & Johnson, 1990; Nieva & Gutek, 1981; Russell, Rush, & Herd, 1988).

Other studies on leadership prototypes and cognitive categorization processes suggest that individuals’ ratings of traits associated with successful leadership vary in self-serving patterns. For example, when rating the prototypicality of traits associated with the social category of leadership, individuals tend to rate positive traits that they believe themselves to possess as more highly prototypical of leadership than traits they do not believe themselves to possess (Dunning, Perie, & Story, 1991).

At the USAFA, each cadet’s military performance is evaluated and documented by officer and cadet leaders through a Military Performance Average (MPA), which is similar to a grade point average. A cadet earns an aggregated rating (on a 4.00 scale) from faculty, peers, and military leaders based on his or her performance in the areas of duty performance, initiative, followership and teamwork, character, and leadership and supervision. Cadets who score high (> 3.00) have been rated as excelling in each of these areas, whereas cadets who score low ( <2.00) are on military probation, are closely monitored, and are provided additional leadership development training to gain the skills essential to become an officer.

Initial empirical research suggests a relationship between perceived successful military leadership characteristics and gender role stereotypes, however, the literature is currently too immature to offer support for a rigorous hypothesis regarding the relationship between performance level and gender-role stereotypes. Therefore, exploratory hypotheses were proposed. It was expected that a cadet’s MPA would be related to his or her perceptions of successful officer stereotypes. These perceptions were expected to differ for male and female cadets, because of the increased salience of their own characteristics (e.g. gender) when making attributions about their own successful leadership performance (Dunning et al., 1991). The following exploratory hypothesis was formulated:

- Hypothesis 3: Perceptions, of successful officers as possessing attitudes, characteristics, and temperaments more commonly ascribed to men in general or women in general, are moderated by cadet performance level and gender.

Seniority and Gender Role Stereotypes

Tenure or length of service was found by Schein (1975) to moderate the relationship between gender role stereotypes and perceived requisite management characteristics. In Schein’s study, managers with greater than 5 years of service perceived “women” and “managers” as more similar than did their junior counterparts (Schein, 1975). Likewise, results of recent studies and reviews (Eagly & Johnson, 1990; Karau & Eagly, 1999; Kolb, 1999) have suggested that experience and time diminish the perceived importance of masculinity in leadership stereotypes.

As indicated earlier, the USAFA provides structured opportunities for cadets to learn and develop as leaders throughout their 4-year education. Cadets take academic courses on leadership from USAFA civilian and military faculty, and they participate in leadership development workshops.

In addition, cadet careers span a leadership hierarchy, and they take on actual work roles in this hierarchy: freshmen are considered subordinates, sophomores are administrators, juniors are first line supervisors, and seniors are commanders or upper management. Because senior cadets have had ample opportunities to study and experience leadership, increased seniority may be related to weaker masculine gender role stereotypes for officer leadership.

On the other hand, if the institutional culture strongly links masculine gender role stereotypes with leadership, increased seniority may be related to more strongly held masculine gender role stereotypes for the officer role. Thus, seniority was investigated as an exploratory variable that serves as a moderator in gender role stereotypes for leadership.

- Hypothesis 4: Perceptions, of successful officers as possessing attitudes, characteristics, and temperaments more commonly ascribed to men in general or women in general, are moderated by cadet seniority.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from the USAFA, a 4-year undergraduate military service college. Student participants were identified to represent 15 of the 40 total cadet squadrons. The 15 squadrons that participated in the study were chosen by a random numbers generator. Each cadet squadron is composed of approximately 120 randomly assigned cadets across all four class years. Only 10-16 women reside in each squadron. To increase response rates from women, three female athletic teams (softball, rugby, and swimming) were also surveyed. Seven hundred ninety surveys were administered, and 755 (96%) were usable. Surveys were eliminated if:

- demographic data, specifically sex, was not reported;

- over 10% of the items were not rated;

- no variability was demonstrated in item ratings.

Of the 755 volunteers who completed usable surveys, 635 were men and 140 were women. Responses by class year included 149 seniors, 170 juniors, 224 sophomores, and 212 freshmen (20 surveys did not include class year). Cadets ranged in age from 17 to 24 years; the mean student age was 20.08 years. Nearly one-third of the cadet respondents indicated that they had not been directly supervised by a female cadet commander; nearly one-fourth of the respondents reported having had at least two female cadet commanders. Respondents’ MPA ranged between 1.00 and 4.00; the mean cumulative MPA was 2.84.

Materials

The Schein 92-item Descriptive Index (Brenner et al., 1989; Schein, 1973, 1975; Schein et al., 1989) was used to identify both gender role stereotypes and characteristics of successful officers. Three forms of the questionnaire were used. All forms contained the same descriptive terms and instructions. However, one form asked for a description of women in general, one for a description of men in general, and one for a description of successful officers. Each cadet received only one form of the questionnaire.

The instructions on the three forms of the descriptive index were as follows:

- On the following pages you will find a series of descriptive terms commonly used to characterize people in general. Some of these terms are positive in connotation, others are negative, and some are neither very positive nor very negative.

- We would like you to use this list to tell us what you think (women in general, men in general, successful officers) are like. In making your judgments, it may be helpful to imagine that you are about to meet a person for the first time and the only thing you know in advance is that the person is (an adult female, an adult male, or a successful officer). Please rate each word or phrase in terms of how characteristic it is of (women in general, men in general, successful officers).

Respondents rated the descriptive terms on a 5-point scale: 5 indicated “characteristic,” 3 indicated “neither characteristic nor uncharacteristic,” and 1 indicated “not characteristic.” Procedure The three versions of the modified Descriptive Index were distributed in an alternating manner so that a similar number of each form was completed by each class year. Trained data collectors informed the cadets that their participation was completely voluntary and confidential. The cadets were not told that there were different versions of the form.

Of the 775 usable questionnaires collected, 267 (34.5%) were completed on “men in general,” 274 (35.4%) on “women in general,” and 234 (30.2%) on “successful officers.” The large sample size facilitated the segmentation of the respondents for secondary analyses. However, even a sample of this size has limitations. Each analysis required first a split into thirds (by questionnaire form), then a split by gender, which yielded cell sizes that ranged from 180 to 231 for male participants and from 36 to 54 for female participants.

Secondary analyses, such as those on the variable MPA, required a further split that identified only a small group of women who had earned low MPAs (n = 34). Further gradations of variables might shed further light on women’s perceptions, but female sample sizes became inadequate to generate confidence in the patterns. Therefore, the secondary analyses are reported for the male participants only.

Results

In a replication of Schein and colleagues’ analysis procedures (Schein, 1973, 1975; Schein et al., 1989), the degree of resemblance between the descriptions of “men” and “officers” and between “women” and “officers” was determined by computing intraclass correlation coefficients from two randomized-groups analyses of variance (see Hays, 1963). The classes (or groups) were the 92 descriptive items. In the first analysis, the scores within each class were the mean item ratings of “men” and “officers,” whereas in the second analysis they were the mean item ratings of “women” and “officers.” According to Hays, the larger the value of r’, the more similar the observations in the class tend to be relative to observations in different classes. Thus, the smaller the within-item variability, relative to the between-item variability, the greater the similarity between the mean item ratings of either “men” and “officers” or “women” and “officers.” These analyses were performed separately for the male and female samples.

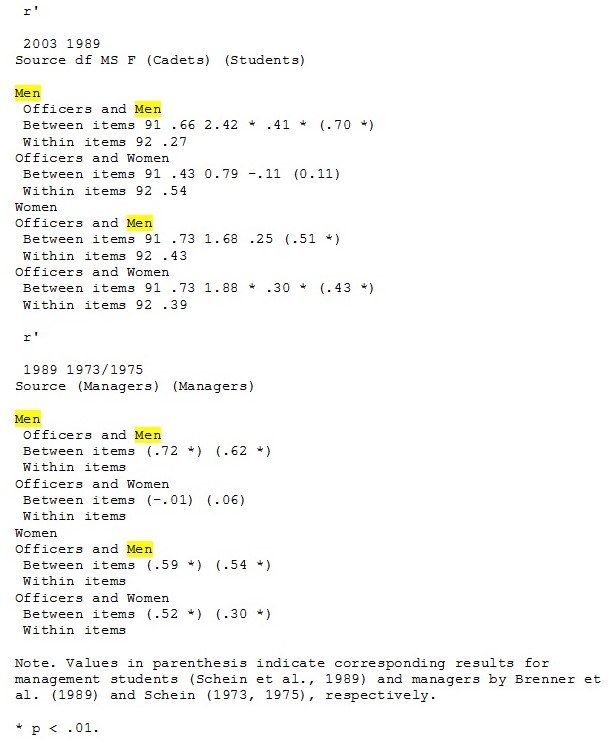

Intraclass correlation coefficients and the results of the analyses of variance mean item ratings are shown in Table 1. For comparison, intraclass correlation coefficients from the Schein et al. (1989), Brenner et al. (1989), and Schein (1973, 1975) studies are included.

Table 1. Aalyses of Variance of Mean Item Ratings and Intraclass Coefficients.

There was a significant resemblance between the ratings by male cadets of “men” and “officers” (r’ =.41, p <.01), whereas there was no significant resemblance between their ratings of “women” and “officers” (r’ = -.11, ns). These results confirm the hypothesis that the men would perceive military leaders as possessing characteristics more commonly ascribed to men in general than to women in general. As shown in Table 1, these results are similar to the results of previous studies.

There was a significant resemblance between the ratings by female cadets of “women” and “officers” (r’ =.30, p <.01), but not between “men” and “officers” (r’ =.25, ns). However, these intraclass coefficients were not significantly different from each other (z = 0.36, ns). Therefore, the hypothesis that women would perceive successful military leaders as possessing characteristics more commonly ascribed to men than to women was not confirmed. These results are similar to results of previous research, which showed that women managers’ perceptions of the resemblance between men and managers were not significantly greater than between women and managers (Brenner et al., 1989). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported only for male cadets.

Comparison of Responses by Work Experience With Women Leaders

The effect of exposure to women leaders on the relationship between gender role stereotypes and requisite officer characteristics was examined. The male cadets were divided into two experience levels:

- those who had not worked for female commanders

- those who had worked for two or more female commanders.

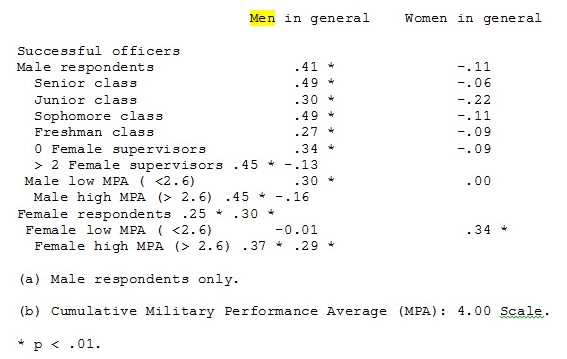

Cadets who had experience with only a single female commander were not included as their ratings would conceivably be biased by the influence of the style and effectiveness of the particular woman. Included in Table 2 are the intraclass correlation coefficents computed between the mean ratings of the descriptions of “men” and “officers” and between the ratings of “women” and “officers” within the two experience levels.

Table 2. Intraclass Correlation Coefficients by Gender, Seniority/Class Year, (a) Female Leadership, (a) and Performance (b).

For men with no experience of women leaders and men with several experiences of women leaders, there was a significant resemblance between the ratings of “men” and “officers” (r’ =.34, p <.01, and r’ =.45, p <.01, respectively) and a nonsignificant resemblance between the ratings of “women” and “officers” (r’ = -.09, ns, and r’ = -.13, ns, respectively).

Further, there was no significant difference between the intraclass correlation coefficients for the different experience levels. Therefore, the second hypothesis that respondents who have more experience and exposure to women leaders would perceive successful military leaders as possessing traits typically associated with both men and women was not supported.

Comparison of Responses by Successful Leadership Performance

To determine whether successful leadership performance moderates the demonstrated relationship between gender, gender role stereotypes, and requisite officer characteristics, the total sample was divided into two levels of performance, high and low. Because the numbers of low-performing female respondents were small, an interrater reliability analysis was performed to determine the consistency of ratings. Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .83 to .92 for female high- and low-performing respondents, respectively, whereas the Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .88 to .93 for low- and high-performing male respondents, respectively. As all reliabilities were relatively high, we proceeded with the data analysis.

As shown in Table 2, the results indicate that level of performance did not moderate the male respondents’ perceptions regarding the similarities between “men” and “officers” and between “women” and “officers.” Statistically the same pattern of intraclass correlation coefficients was found for both performance levels, in that both low- and high-performing men rated “men” and “officers” as similar (r’ =.30, p <.01, and r’ =.45, p <.01, respectively) and “women” and “officers” as dissimilar (r’ =.00, ns, and r’ = -.16, ns, respectively). Performance level did moderate the gender role stereotypes exhibited by female respondents. Low-performing women did not show a significant correlation between the ratings of “men” and “officers” (r’ = -.01, ns), but did show a moderate correlation between ratings of “women” and “officers” (r’=.34, p <.01).

Higher performing women demonstrated a moderate and significant correlation between the ratings of “men” and “officers,” and between “women” and “officers” (r’ =.37, p <.01, and r’ =.29, p <.01, respectively). This difference in perceptions regarding similarities between “men” and “successful officers” by low- and high-performing female respondents (r’ = -.01, ns, and r’ =.37, p <.01), was statistically significant (z = 2.66, p <.01). Further, the difference in perceptions regarding the similarities between “women” and “successful officers” by high-performing male and female cadets (r’ = -.16, ns, and r’ =.29, p <.010, respectively) was also statistically significant (z = 3.07, p <.01).

Therefore, partial support was provided for the exploratory hypotheses, in that successful female cadets’ perceptions of a successful military leader include traits commonly ascribed to women, whereas successful male cadets maintained a predominantly masculine perception of a successful leader. However, contrary to the hypothesis explored, female successful performers expanded their perceptions of successful military leaders to include traits commonly ascribed to men as well as women, whereas their lower performing counterparts described military leaders in feminine terms.

Comparison of Responses by Seniority

The effect of seniority upon the relationships between gender role stereotypes and requisite officer characteristics was also examined. Table 2 shows the intraclass correlation coefficients computed between the mean ratings of “men” and “officers” and between the ratings of “women” and “officers” within the four class years for male respondents only.

The results reveal that length of service did not have an effect upon the relationships. Among male respondents with more than 1 year at the military academy, the intraclass correlation coefficients between ratings of “men” and “officers” were.49,.30, and.49, p <.01, for the senior, junior, and sophomore cadets respectively. Responses from men with less than 1 year of service did not demonstrate a significant resemblance between the mean ratings of “men” and “officers” (r’ =.27, p <.01). However, the intraclass correlation was not significantly higher for sophomore, junior, and senior cadets compared to freshman cadets (z = 1.73, ns). The intraclass coefficients between ratings of “women” and “officers” were not significantly different by seniority. These results are similar to the Brenner et al. (1989) study, but counter to Schein’s (1975) study; they do not support the prediction that seniority would moderate cadets’ perceptions of gender role stereotypes.

Descriptive Items

Although an understanding of the resemblance between the mean descriptive ratings of men and officers and women and officers was our primary interest, an exploratory examination of the specific descriptive items on which “men” or “women” were perceived as different from “officers” was made by performing multivariate analyses of variance with post hoc Tamhane’s T2 analyses. Tamhane’s T2 is a conservative post hoc pairwise comparisons test for unequal sample sizes. An alpha level of.001 was used as the criterion of significance.

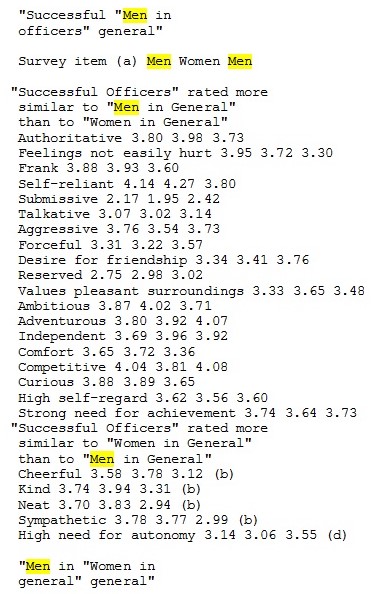

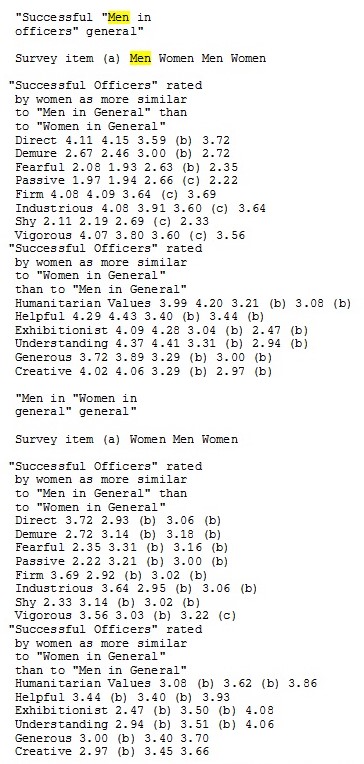

The analyses incorporated the three groups (“officer,” “men,” and “women” surveys) and the two genders (men and women cadets) for the 92 items. The 24 items where “successful officers” were rated differently from “women in general,” or where “successful officers” were rated differently from “men in general,” are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Item Mean Scores Rated Significantly Different Between Surveys by Gender.

The results reveal that men rated 19 items as more similar between “officers” and “men” than between “officers” and “women.” As shown in Table 3, both male and female respondents rated “officers” as significantly different from “women” and similar to “men” on five items (authoritative, feelings not easily hurt, frank, self-reliant, and submissive). Male respondents rated “officers” as significantly different from “women” and similar to “men” on 14 additional items (e.g., talkative, aggressive, desire for friendship, forceful, reserved).

For example, the mean male cadets ratings of aggressive and forceful in describing “successful officers” (Ms = 3.76 and 3.31, respectively) were statistically different from the mean male and female cadets ratings of these adjectives in describing “women in general” (Ms = 2.86 and 2.76, respectively). In comparison, the female cadets’ ratings of “successful officers” (Ms = 3.54 and 3.22) were not statistically different from the male and female cadets’ ratings of “women in general” on these two adjectives. Both men and women rated “successful officers” as similar to “women in general” and significantly different from “men in general” on four items (cheerful, kind, neat, and sympathetic). Women also rated “successful officers” and “women in general” as similar on one additional item, need for autonomy.

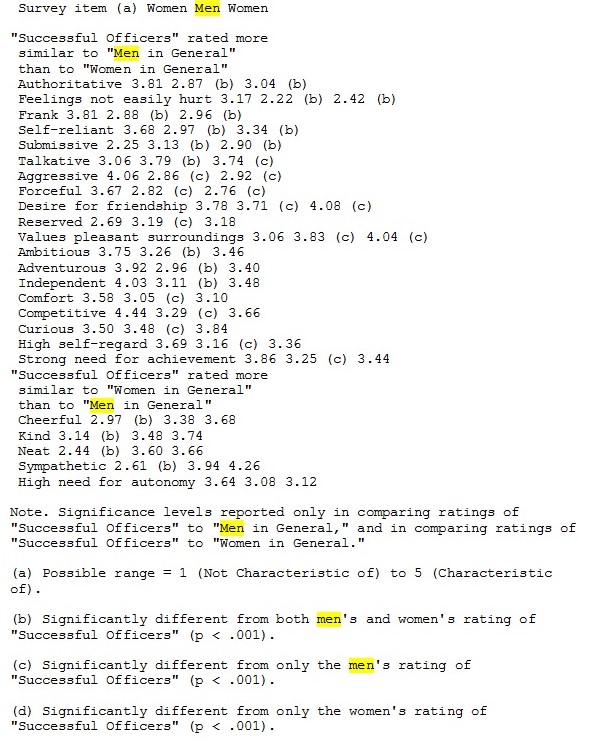

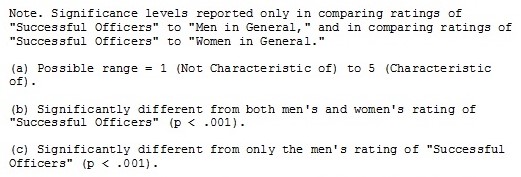

Table 4 depicts items where women in particular rated “successful officers” as similar to “men in general” or to “women in general.” As shown in Table 4, women rated “successful officers” as more direct, firm, and industrious, and less demure, fearful, passive, and shy than “women in general.” In contrast, men rated “successful officers” as significantly different from both “men in general” and “women in general” on these eight characteristics.

Table 4: Item Mean Scores Rated Significantly Different Between Surveys by Gender.

Both men and women rated “successful officers” as similar to “women in general” on two items (generous and creative). Women rated “successful officers” and “women in general” as similar on four additional items (humane, helpful, exhibitionist, understanding, generous). These results suggest that female cadets are more likely to use the same terms in describing women, men, and successful officers.

Discussion

This study produced several interesting outcomes including:

- men’s perceptions of the lack of similarities between women and leaders,

- support of previous findings that indicated that women recognize similarities between women and leaders,

- greater experience with being led by female commanders did not change the men’s masculine stereotype of successful leaders,

- the surprising finding that senior-level male cadets possess stronger masculine stereotypes of successful officers than do freshman male cadets,

- men, regardless of their level of performance, maintained a masculine stereotype of leaders.

Successful female leaders, however, perceived successful officers as having characteristics commonly associated with both men and women, whereas their less successful counterparts perceived successful military leaders as possessing characteristics, attitudes, and temperaments more commonly ascribed to women in general than to men in general.

Despite the changes in the military to include admission of women into military academies and some combat roles, the underlying stereotypical perceptions of leadership in the military are masculine in nature. Results of the study indicate that men at the USAFA share attitudes similar to those of civilian managers 25 years ago (Schein, 1973, 1975).

Results of this study also suggest that increased experience and seniority in the military environment may increase, rather than decrease, the pattern of masculine stereotyping of the officer/leader role. Unlike previous civilian findings that indicated that managerial experience modified stereotypical perceptions, this cadet military sample’s responses indicate that experience with leadership and seniority at the military academy maintained or increased masculine stereotyping. Researchers (Karau & Eagly, 1999; Powell, 1993; Schein, 1973) have suggested that increased exposure to women as managers helps modify perceptions of masculine gender role stereotypes of the leadership role.

However, examination of male cadets’ perceptions by exposure to or experience with women leaders indicated that experience was not related to the degree of masculine stereotyping. In this study, men who had worked for two or more female commanders perceived requisite officer characteristics to be stereotypically male-oriented, which was the same view reported by men who had never worked for a female commander.

These results, as well as those from studies of other military populations (Boldry et al., 2001; Youngman, 2001), may indicate that the culture of the military academy is so strongly masculine that senior cadets who have been involved in this culture perceive successful leadership characteristics to be masculine to a greater extent than do junior cadets who have not been as long exposed to the academy culture. On the other hand, the cross-sectional study design poses a limitation in interpreting the results related to the seniority variable, because it is possible that the perceptions of the junior and senior cadet classes were somehow inherently different. A longitudinal study design would better answer questions regarding the effect of seniority on cadets’ perceptions of gender role and leadership.

Results of this study did not confirm the hypothesis that more successful female cadets would gender-type the officer job as requiring primarily feminine characteristics, in light of the self-serving biases demonstrated in previous studies of leadership prototyping (Dunning et al., 1991). Rather, similar to the Schein et al. (1989) study of management students, successful female cadets perceived women and men both to possess characteristics necessary for military leadership success. If this gender-free view of requisite officer characteristics continues as these women advance as officers, we might expect them to treat men and women more equitably, on the basis of performance criteria rather than gender role expectations, in their selection and promotion decision processes.

In contrast to the more successful female cadets in this study, female cadets with lower military performance averages rated the successful officer as possessing traits associated with women. These results may be due to the female cadets’ own self-descriptive attributes; that is, if the less successful female cadets describe themselves in more feminine terms than do their more successful counterparts, they may be weighting these feminine traits more strongly when describing the successful officer, as predicted by the self-serving biases found in leadership prototype studies (Dunning et al., 1991). It is also possible that the perceptions of the less successful female cadets (that successful officers possess feminine traits) are partly responsible for lower performance ratings in an environment where most of their peers have different perceptions.

Along these lines, it is interesting to note that in the study of military students cited earlier by Boldry et al. (2001), female military trainees rated themselves as more feminine and less masculine than male trainees rated themselves, yet there were no differences between the men’s and women’s self-ratings of their motivation, leadership, and character. Thus, further research is needed to clarify cadets’ self-assessments of their own leadership potential and gender roles in relation to their gender role stereotypes of military officers.

Limitations and Future Directions

In addition to the cross-sectional nature of the study, limitations of this study include the use of a questionnaire to measure abstract perceptions of leadership rather than actual leader behavior and performance outcomes among men and women leaders. Laboratory studies, compared with field studies of actual behavior, typically exaggerate the salience of gender differences in perceptions of leadership (Eagly & Johnson, 1990; Klenke, 1996).

Current research on gender issues in leadership as well as the study’s design limitations suggest a variety of important avenues for future research. One set of variables for future research concerns individual difference variables such as gender role orientation and attitudes toward leadership. Studies of gender role identity in relation to managerial aspirations have suggested that both women and men with managerial aspirations score high on scales that measure masculinity (Marshall & Wijting, 1980). These scales include many of the traits that are perceived as necessary for leadership, such as dominance, responsibility, achievement, and self-assurance (Kolb, 1996, 1999; Powell, 1988; Steinberg & Shapiro, 1982).

In addition, it has been suggested that “people choose careers that are consistent with their self-image” (Korman, 1970, p. 32). Because the military is traditionally recognized as a masculine institution, it is likely that the military academies would attract women and men with more traditional views, including expectations that effective leaders are masculine. Feminine applicants or those who do not expect “masculine” leadership styles may be less likely to apply to the USAFA. Consistent with this interpretation is the finding that military trainees in the study by Boldry et al. (2001) rated the ideal cadet as low in femininity.

Another question for future study is whether expectations regarding masculine leadership characteristics have positive or negative, consistent or differential effects for male and female cadets. Role congruency theory suggests that the “male managerial model” poses barriers for women who aspire to leadership positions, because if women engage in expected feminine behaviors they may be seen as not able to behave in a way congruent with appropriate leadership behaviors (Eagly et al., 1995).

However, some studies of the evaluation of leader behaviors have suggested that women who are successful in stereotypically masculine environments may be evaluated more favorably than their male counterparts (Eagly & Johnson, 1990; Eagly, Mladinic, & Otto, 1991; Nieva & Gutek, 1981; Thompson, 2000). Because masculine characteristics are not directly linked to sex (Kolb, 1999), it is possible that women who apply, are accepted, and who opt to stay in the military academy are perceived favorably by their peers and leaders because they are able to perform successfully in roles that differ from those considered traditionally feminine. Likewise, motivation to control prejudice has been found to be an important variable in the evaluation of women’s leadership (Ziegert & Hanges, 2002).

Thus, studies of actual gender differences in cadet leader behavior, and differences in the evaluations of these behaviors, are warranted. Similarly, studies in which perceptions of the extent of, and conditions correlated with, military women’s leadership effectiveness are measured directly would help to clarify the extent to which gender role stereotypes serve as barriers against women’s entry into and success in military leadership positions.

A more difficult question to research, but one that is potentially quite important, is the underlying validity of assumptions regarding the masculine nature of successful leadership in the military organization to achieve the organization’s objectives. It is widely recognized that the military has had an enduring culture that is primarily “masculine” in nature. It could be argued that the American military has been largely successful in achieving national and international military objectives throughout America’s history. On the other hand, just as civilian organizations are characterized by unprecedented change in their environments and required operations, so is the military of the twenty-first century characterized by unprecedented change in its range of missions and operations.

The current war on terrorism, as well as a variety of peacekeeping missions in which the U.S. military is currently engaged across the globe, have required the unprecedented increases in use of U.S. special operations forces (Burns, 2002). Unlike the conventional military, these special forces are organized into much smaller, more flexible team units, trained to conduct the gamut of unconventional missions including humanitarian, special reconnaissance, foreign internal defense, and guerilla warfare missions (Burns, 2002). It seems likely that the increased demands placed on the military by the global war on terrorism, as well as increased number and range of unconventional missions, will also lead to increased demands on military leadership.

A host of current researchers and management practitioners have posited the need for less gender-typed approaches to leadership (e.g., Rosener, 1990), and the benefits of “balanced,” more wide-ranging, and flexible leadership orientations to meet changing demands on organizations (Thompson, 2000). These exhortations seem to apply to both military and civilian organizations in today’s fast-changing world. Transformational and charismatic approaches to leadership, which are seen as less incongruent with women’s roles than traditional masculine leadership approaches, might be especially appropriate during times of change and crisis, such as the war on terrorism (Carless, 1998; Conger & Kanungo, 1998; Rosener, 1990; Thompson, 2000; Yoder, 2001).

Practical Implications

Suggestions for overcoming possible leadership barriers posed by gender role stereotypes in masculine organizational cultures include individual, organizational, and contextual strategies (Bajdo & Dickson, 2002; Heilman, 2001; Heilman et al., 1989; Loden, 1985; Ragins, Townsend, & Matthis, 1998; Yoder, 2001).

At the individual level, women are encouraged to use communal gender-congruent leadership styles, build trust before attempting to influence their group, and increase the salience of their task-related competencies to decrease status differences between themselves and their followers and also to increase their perceived status. At the military academy, academic as well as military leadership courses could specifically include research on the gendered context of leadership and the equifinality of various leadership styles.

Organizational strategies for enhancing women’s leadership opportunities include making clear the measurement of and criteria for leadership performance and promotion decisions (Ragins et al., 1998: Ragins & Sundstrom, 1989; Yoder, 2001). Legitimating women selected as leaders has also been shown to increase their effectiveness (Yoder, Schleicher, & McDonald, 1998). At the military academy, explicit publication of the skills and competency criteria used to select cadet leaders would benefit women and men who are selected for leadership positions.

Contextual strategies for enhancing women’s leadership effectiveness focus primarily on minimizing the negative effects of tokenism (Kanter, 1977: Yoder, 2001). To this end, several researchers have suggested ensuring that work groups are composed of at least 35% women to make them congenial for women’s leadership and to reduce gender role stereotyping (Tolbert, Simons, Andrews, & Rhee, 1995; Yoder, 2001).

At the military academy, the small percentage of female cadets is evenly distributed among the cadet squadrons so that female cadets usually have token status (less than 15%) in all the squadrons. In light of research on the negative effects of tokenism, the costs and benefits of increasing the percentage of female cadets in some squadrons (and thus decreasing the percentages in others) should be assessed.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the United States Air Force Academy (USAFA), Department of Behavioral Sciences (DFBL) and the USAFA Corbin Counsel. The authors thank two anonymous reviewers for their comments on an earlier draft of this article.

- Portions of this paper were presented at the 108th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, August 2000.

- Schein’s original Descriptive Index, which requested ratings of “successful middle managers,” was modified, with permission, to “successful officers” to meet the needs of this study.

- The authors thank the Editor for this alternative explanation.

References

Arkins, W., & Dobrofsky, L. R. (1978). Military socialization and masculinity. Journal of Social Issues, 34, 151-168.

Bajdo, L. M., & Dickson, M. W. (2002). Leadership preferences, organizational culture, and women’s advancement in organizations. Paper presented at the meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Toronto, Canada.

Baron, A. (1984). The achieving woman manager: So where are the rewards? Business Quarterly, 49, 70-73.

Bartol, K. M., & Butterfield, D. A. (1976). Sex effects in evaluating leaders. Journal of Applied Psychology, 61, 446-454.

Bass, B. M., Krusell, J., & Alexander, R. A. (1971). Mate managers’ attitudes toward working women. American Behavioral Scientist, 15, 221-236.

Boldry, J., Wood, W., & Kashy, D. A. (2001). Gender stereotypes and the evaluation of men and women in military training. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 689-705.

Bowman, G. W., Worthy, N. B., & Greyser, S. A. (1965). Are women executives people? Harvard Business Review, 43, 15-28, 164-178.

Brenner, O. C., Tomkiewicz, J., & Schein, V. E. (1989). The relationship between sex role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics revisited. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 662-669.

Broverman, I. K., Broverman, D. M., Clarkson, F. E., Rosenkrantz, P., & Vogel, S. R. (1970). Sex-role stereotypes and clinical judgments of mental health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 34, 1-7.

Broverman, I. K., Vogel, S. R., Broverman, D. M., Clarkson, F. E., & Rosenkrantz, P. S. (1972). Sex role stereotypes: A current appraisal. Journal of Social Issues, 28, 59-78.

Burns, R. (2002). Special operations role grows. The Fayetteville Observer, p. 11A.

Carless, S. A. (1998). Gender differences in transformational leadership: An examination of superior, leader, and subordinate perspectives. Sex Roles, 39, 887-902.

Colaw, R. S. (Ed.). (1996). Women in motion. Available from HQ/USAFA/PA, 2304 Cadet Drive. Suite 320, USAF Academy, CO 80840-5016.

Conger, J. A., & Kanungo, R. N. (1998). Charismatic leadership in organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Devilbiss, M. S. (1990). Women and military service: A history, analysis, and overview of key issues. Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Air University Press.

Dobbins, G. H., & Platz, S. J. (1986). Sex differences in leadership: How real are they? Academy of Management Review, 11, 118-127.

Dodge, K. A., Gilroy, F. D., & Fenzel, L. M. (1995). Requisite management characteristics revisited: Two decades later. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 10, 253-264.

Dunning, D., Perie, M., & Story, A. L. (1991). Self-serving prototypes of social categories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 957-968.

Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Eagly, A. H., & Johnson, B. T. (1990). Gender and leadership style: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 233-256.

Eagly, A. H., Karau, S. J., & Makhijani, M. G. (1995). Gender and the effectiveness of leaders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 125-145.

Eagly, A. H., Makhijani, M. G., & Klonsky, B. G. (1992). Gender and the evaluation of leaders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 111, 3-22.

Eagly, A. H., Mladinic, A., & Otto, S. (1991). Are women evaluated more favorably than men? An analysis of attitudes, beliefs, and emotions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 15, 203-216.

Hays, W. L. (1963). Statistics for psychologists. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Heilman, M. E. (2001). Description and prescription: How gender stereotypes prevent women’s ascent up the organizational ladder. Journal of Social Issues, 57(4), 657-674.

Heilman, M., Block, C., Simon, M. C., & Martell, R. F. (1989). Has anything changed? Current characterizations of men, women, and managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 935-942.

Johnson, M. M. (1997). Women’s status in military examined. Coast Guard Academy News, pp. A3, A4.

Kanter, R. M. (1977). Men and women of the corporation. New York: Basic Books.

Karau, S. J., & Eagly, A. H. (1999). Invited reaction: Gender, social roles, and the emergence of leaders. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 10, 321-327.

Klenke, K. (1996). Women and leadership: A contextual perspective. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Kolb, J. A. (1996). A comparison of leadership behaviors and competencies in high- and average-performance teams. Communications Reports, 9, 173-183.

Kolb, J. A. (1999). The effect of gender role, attitude toward leadership, and self-confidence on leader emergence: Implications for leadership development. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 10, 305-320.

Korman, A. K. (1970) Toward an hypothesis of work behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 54, 31-41.

Loden, M. (1985). Feminine leadership, or how to succeed in business without being one of the boys. New York: Times Books.

Manning, L., & Wright, V. R. (2000). Women in the military: Where they stand.

Washington, DC: Women’s Research and Education Institute.

Marshall, S. J. & Wijting, J. P. (1980). Relationships of achievement motivation and sex-role identity to college women’s career orientation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 16, 299-311.

Nieva, V. F., & Gutek, B. A. (1981). Women and work. New York: Praeger.

Norris, J. M., & Wylie, A. M. (1995). Gender stereotyping of the managerial role among students in Canada and the United States. Group and Organization Management, 20, 167-181.

Powell, G. N. (1990). One more time: Do female and male managers differ? Academy of Management Executive, 4, 68-75.

Powell, G. N. (1993). Women and men in management (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Ragins, B. R., & Sundstrom, E. (1989). Gender and power in organizations: A longitudinal perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 105, 51-88.

Ragins, B. R., Townsend, B., & Matthis, M. (1998). Gender gap in the executive suite: CEOs and female executives report on breaking the glass ceiling. Academy of Management Executive, 12, 28-42.

Rosen, B., & Jerdee, T. H. (1973). The influence of sex-role stereotypes of evaluations of male and female supervisory behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 57, 44-48.

Rosen, B., & Jerdee, T. H. (1974a). Effects of applicant’s sex and difficulty of job on evaluations of candidates for managerial positions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59, 511-512.

Rosen, B., & Jerdee, T. H. (1974b). The influence of sex-role stereotypes in personnel decisions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59, 9-14.

Rosen, B., & Jerdee, T. H. (1978). Perceived sex differences in managerially relevant characteristics. Sex Roles, 4, 837-843.

Rosener, J. B. (1990). Ways women lead. Harvard Business Review, 68, 119-126.

Rudman, L. A., & Kilianski, S. E. (2000). Implicit and explicit attitudes toward female authority. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 1315-1328.

Russell, J. E. A., Rush, M. C., & Herd, A. M. (1988). An exploration of women’s expectations of effective male and female leadership. Sex Roles, 18, 279-287.

Schein, V. E. (1973). The relationship between sex role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 57, 95-100.

Schein, V. E. (1975). The relationship between sex role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics among female managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 340-344.

Schein, V. E. (1978). Sex role stereotyping, ability, and performance: Prior research and new directions. Personnel Psychology, 31, 259-268.

Schein, V. E., Mueller, R., & Jacobson, C. (1989). The relationship between sex role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics among college students. Sex Roles, 20, 103-110.

Steinberg, R., & Shapiro, S. (1982). Sex differences in personality traits of female and male master of business administration students. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67, 306-310.

Thompson, M. D. (2000). Gender, leadership orientation, and effectiveness: Testing the theoretical models of Bowman and Deal and Quinn. Sex Roles, 42, 969-992.

Tolbert, P. S., Simons, T. Andrews, A., & Rhee, J. (1995). The effects of gender composition in academic departments on faculty turnover. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 48, 562-579.

Versaw, P. E. (1997, March). Greetings from the Superintendent of the U.S. Coast Guard Academy. Leadership in a Gender-Diverse Military. Available from the U.S. Coast Guard Academy, Public Affairs Office, New London, CT 06320-4195.

Yoder, J. D. (2001). Making leadership work more effectively for women. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 815-828.

Yoder, J. D., Schleicher, T. L., & McDonald, T. W. (1998). Empowering token women leaders: The importance of organizationally legitimated credibility. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22, 209-222.

Youngman, J. (2001). Women in the military: The struggle to lead. In C. B. Costello & A. J. Stone (Eds.), The American woman 2001-2002: Getting to the top (pp. 139-168). New York: Norton.

Ziegert, J. C., & Hanges, P. J. (2002, April). Evaluation of female leaders: The role of attitudes and motivation. Paper presented at the meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Toronto, Canada.