Introduction

Human resources analysis in hospital setting is critical due to the challenges in this field. The doctor shortage situation has been exacerbated by the healthcare system’s long-term disregard of health workforce management, which lacks a systemic approach or committed organization (Dubas‐Jakóbczyk et al., 2019). The development of workforce indicators must take into consideration a detailed comprehension of how the workforce relates to the activities of the company (Huselid, 2018). In order to hire, organize, and retain employees as well as to cover a lack of personnel, healthcare management in urgent situations necessitates the application of adaptable and contextual workforce management concepts (Poortaghi et al., 2021). The issues related to human resources are a surplus of corporate services and a lack of education and training services that have to be technologically developed.

Attributes of the Total Workforce

Age and Sex Structure of the Workforce

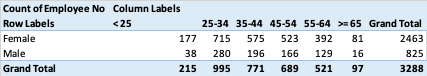

Age and sex structure of the workforce, especially in healthcare settings, are essential since they directly influence the form of the relationships inside an organization or a group. According to researches, there are a number of interrelated metrics and crucial areas of relevance, and initiatives to increase appropriate age management at the institutional level are generally needed (Blomé et al., 2018). Enhancing patient care depends on the structure of the medical workforce and the eradication of workforce disparities (Silver et al., 2019). As per the evaluation and metrics, provided in the table below, the grand total of workforce in the organization is equal to 3288 staff workers. In terms of sex structure of personnel, it is feasible to emphasize a substantial prevalence of female employees, 2463 in comparison to 825 male employees. The largest age segment of workers, 995, belongs to the 25-34 years old age group. Number of employees of the 65+ age group equals 97 and strategy to have older people retained in the workforce might be considered.

Occupational Categories

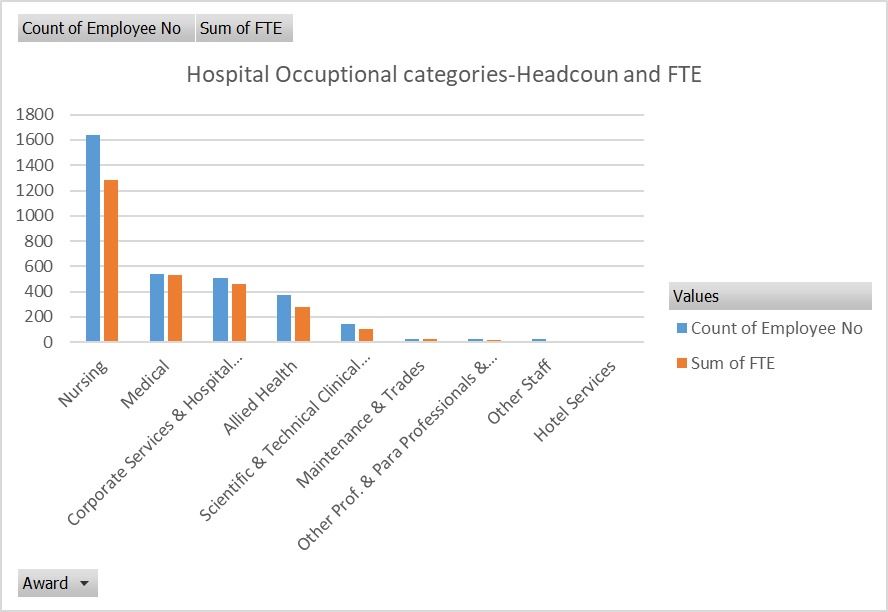

Regarding occupational categories, it is crucial for supervisors to recognize the proportions and quantities of various specialists in order to properly coordinate their functioning and detect potential systematic drawbacks. Personal workplace study might produce helpful indices, but examining the occupational group and categories in healthcare can produce significant findings (Ghahramani et al., 2020). As it is illustrated on Figure 2, it is possible to state that the largest occupation number is connected to nursing in this hospital setting. Among nurses, the majority of the employees are employed full-time; however, a considerable part of nurses are part-time employees. The second occupational category is the medical sphere and workforce is predominantly full-time. This category demands suggesting a large number of training programs since professional development is important for fully-qualified and highly-specialized medical specialists. The third occupational category is linked to corporate services and this segment possesses approximately identical headcount and number of full-time workers comparing to medical professionals. This occupational categorization requires further investigation as healthcare should be predominantly clinical, patient-focused.

Classification Levels

Nursing Classification Levels

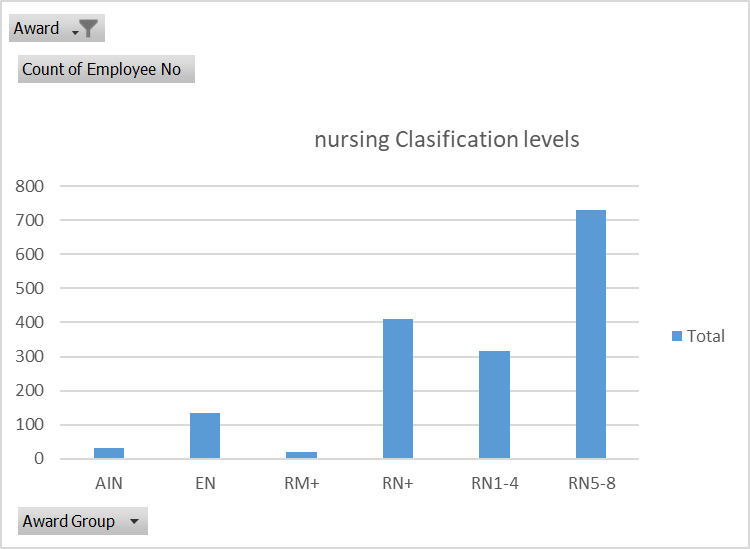

In terms of nursing classification levels in the hospital, it is reasonable to note that the main classification types that are present are AIN, EN, RM+, RN+, RN1-4 and RN5-8. According to the data retrieved from Figure 3, the total number of employees in the field of nursing belong to the RN group, in which the RN5-8 group has the highest value. It is needed to identify at retention strategies for 8+ years of service and investigate opportunities to provide additional AIN to the workforce as a short-term measure to attract nursing students to the hospital. Other strategies can be implemented, for instance, analyzing the results of junior nursing specialists to subsequently include them into the staff.

Medical Classification Levels

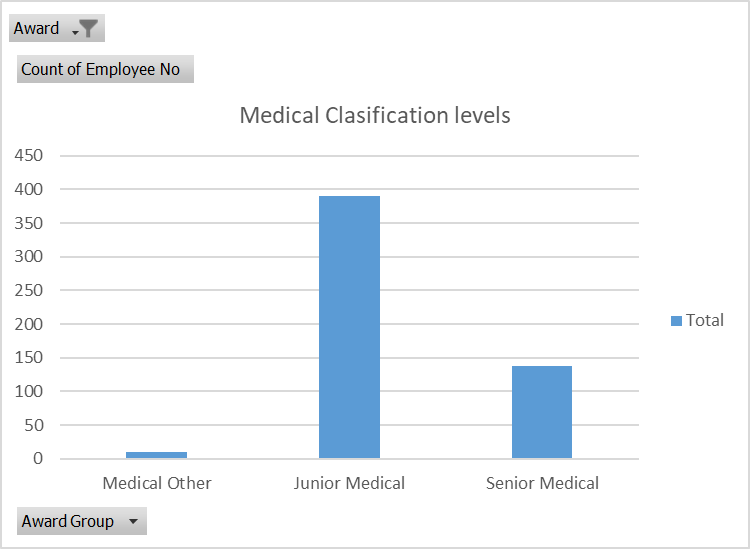

Concerning medical classification levels, as per Figure 4, it is feasible to highlight a substantial prevalence of junior medical employees in comparison with seniors and other specialties. In medical training, peer-assisted instruction often entails senior medical professionals organizing teaching activities for junior medical specialists (Bennett et al., 2018). The hospital has a high proportion of junior medical officers, which indicates that it should ensure maintaining its investment in teaching to retain staff.

Staffing Mix

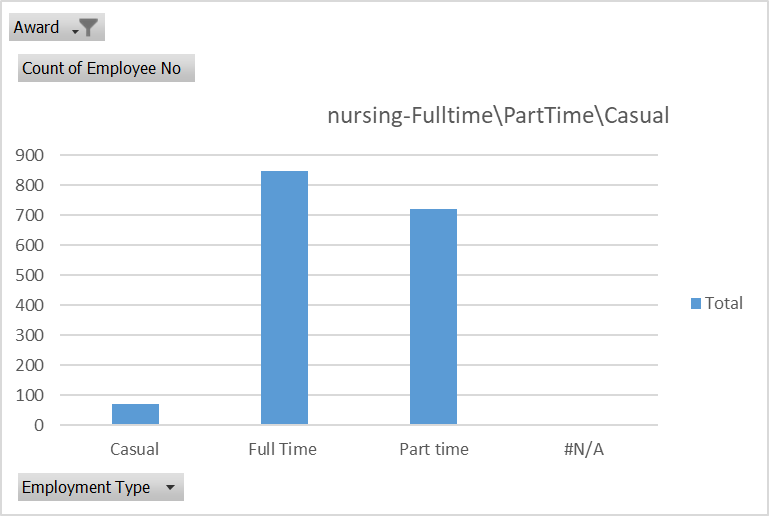

Nursing Staffing Mix

The staffing mix can incorporate part-time, full-time, temporary, and permanent types of staffing. There is a variety of information both inside and outside medicine that supports the positive effects of competence and staffing mix analysis (Peters et al., 2021). As per the Figure 5, full-time and part-time nursing employees constitute the majority and full-time workers are prevalent inside the group. It is essential to maintain training to ensure skills retained and to ensure that return to work post family allows part-time option choice.

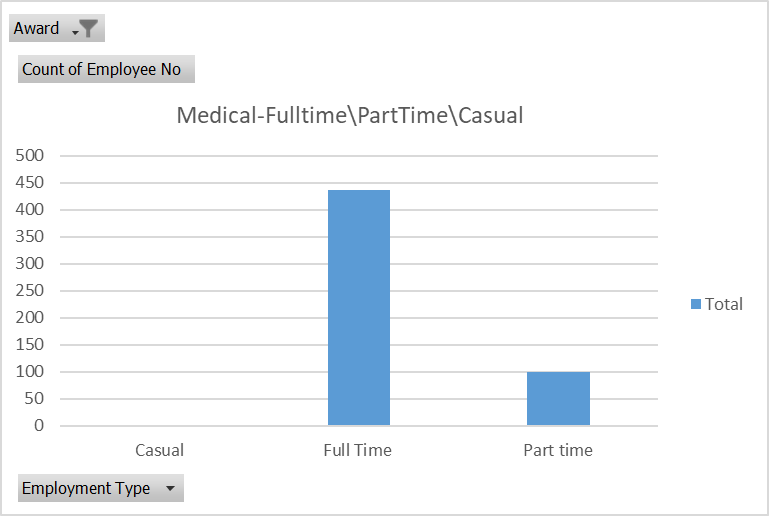

Medical Staffing Mix

Referring to medical staffing, according to Figure 6, the number of full-time medical professionals is approximately five times larger than part-time, which can be linked to delegation activities. The significance of determining how delegation patterns in nursing and medicine is connected to staffing and network connectivity (Beeber et al., 2018). This is a common profile in training hospitals and medical workforce has a similar profile to junior and senior ones, as full-time in training and part-time in senior roles.

Workforce Distribution

Concerning the aspects of workforce distribution, it is possible to note that the workforce is mainly complied of two basic parts: health services and corporate services. In general, ensuring efficiency and effectiveness of workforce distribution is crucial for healthcare facilities (Obamiro et al., 2022). According to the Figure 7, workers in the health service segment represent the highest workforce number with an internal predominant quantity of full-time employees. Hence, he importance of health services is mostly underlined by the administration due to the increased level of workforce distribution.

Average Hours Worked and Overtime Hours

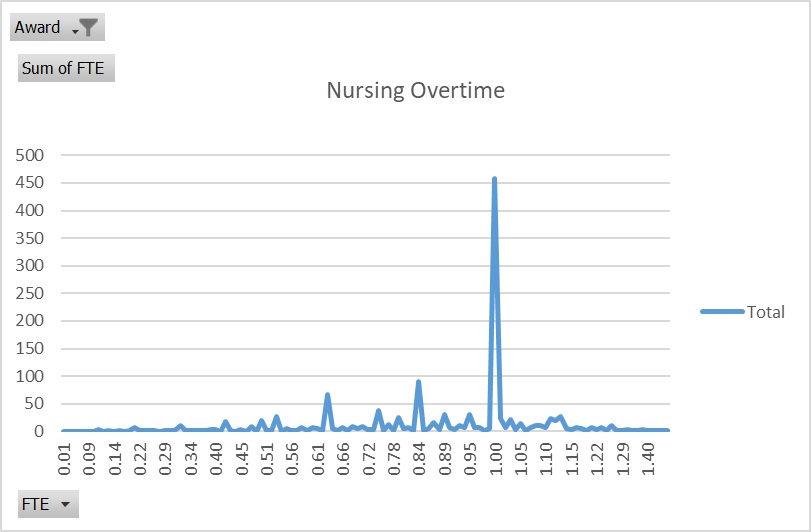

Nursing Overtime

As per Figure 8, 23 people were required to do overtime in nursing in the previous period. Nursing and medical professionals’ overtime work can be related to potential risks, particularly in critical care (D’Sa et al., 2018). There were four people who did 1.5 full-time work of overtime in the past period and there is small number of people working dangerous hours, which should be addressed. Concerning a recommendation for action for nursing, it is obligatory to ensure the full-time practitioners are not influenced by deviations in scheduling and working hours.

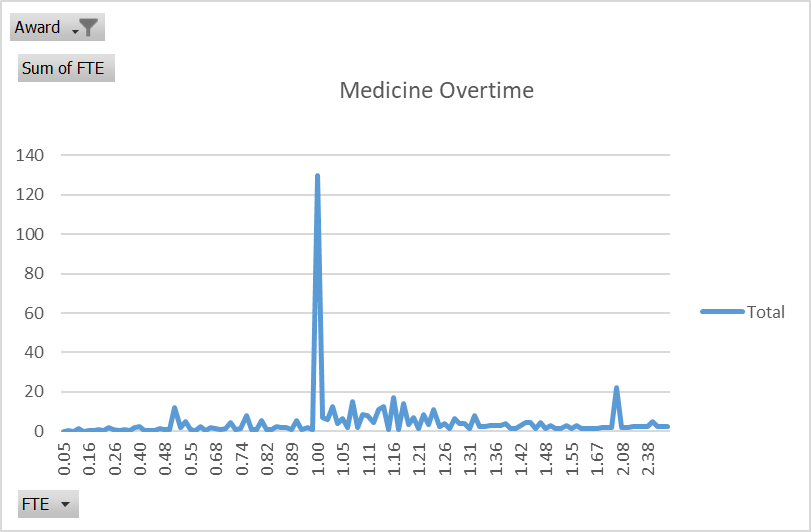

Medical Overtime

According to the data retrieved form Figure 9, it is feasible to state that there is a large proportion of overtime in the medical workforce. In fact, 69 people did overtime in the previous period, 11 did greater than two full-time or 80 hours per week, and two people 2 did greater than 100 hours of work in a week. A recommendation for action for medicine would be to recognize the need for controlling the average and mean values of hours worked.

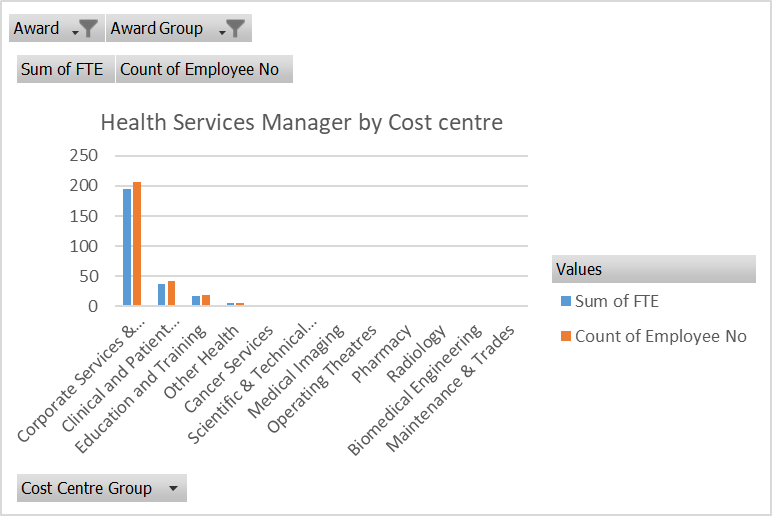

Service Areas Selection

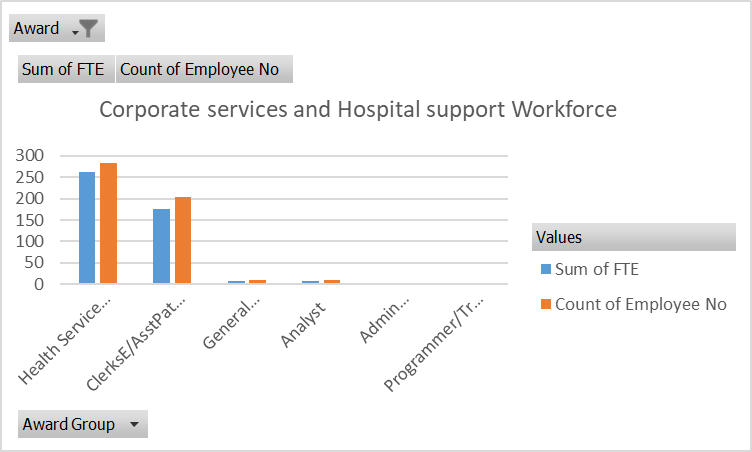

As per the Figure 10, the two service areas that have to be selected are corporate services, as well as education and training. Corporate services were chosen due to the impossibility of maintaining all procedures and activities in a hospital setting without corporate processes, whereas education and training was a preferred option since personnel development is crucial. Corporate services are closely linked to two important stakeholder parties: patients and community and hospital brand awareness (Limbu et al., 2019). It is necessary to design strategies for the education and training of medical specialists, including defined competences for all practitioners (Leff et al., 2022). Corporate services are characterized by an increased amount of non-medical tasks and processes to complete and perform, while education and training segment is related to personnel development policies for medical, nursing, and administrative positions. Comparing to the total workforce of the hospital, corporate services possess the highest number of employees, whereas education and training occupy the third position.

Human Resources Challenges and Recommendations

Concerning the human resources challenges the hospital is facing based on the data analysis, it is reasonable to underline the prevalence of corporate and support services, as well as the lack of education and training. Considering medicine and pharmaceutics, additional consultation and training can result in improved clinical service provision and reputation (Xu et al., 2019). In order to make the best possible use of the human resources already on staff, healthcare institutions must fully utilize technology (Chakraborty & Khan, 2019). It can be recommended that the corporate service and hospital support review the situation and identify opportunities for reduction in corporate services to become clinical and service-focused.

Conclusion

To summarize, based on the data analysis, it is appropriate to highlight the presence of corporate and support services, the absence of education and training, as well as the human resource issues the hospital is experiencing. It may be advised that corporate services and hospital support evaluate the situation and explore ways to greatly reduce on corporate services so they can become more clinical and service-focused. Corporate services are distinguished by a rise in non-medical work, whereas the education and training sector is concerned with staff development guidelines.

References

Beeber, A. S., Zimmerman, S., Madeline Mitchell, C., & Reed, D. (2018). Staffing and service availability in assisted living: The importance of nurse delegation policies.Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(11), 2158-2166.

Bennett, S. R., Morris, S. R., & Mirza, S. (2018). Medical students teaching medical students surgical skills: The benefits of peer-assisted learning.Journal of Surgical Education, 75(6), 1471-1474.

Blomé, M. W., Borell, J., Håkansson, C., & Nilsson, K. (2018). Attitudes toward elderly workers and perceptions of integrated age management practices. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 26(1), 112-120.

Chakraborty, M., & Khan, K. M. A. (2019). A case study on the importance of human resource information system in the healthcare sector of a corporate hospital in India.International Conference on Digitization, 115-117.

D’Sa, V. M., Ploeg, J., Fisher, A., Akhtar-Danesh, N., & Peachey, G. (2018). Potential dangers of nursing overtime in critical care.Nursing Leadership, 31(3), 48-60.

Dubas‐Jakóbczyk, K., Domagała, A., & Mikos, M. (2019). Impact of the doctor deficit on hospital management in Poland: A mixed‐method study.The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 34(1), 187-195.

Ghahramani, R., Kermani-Alghoraishi, M., Roohafza, H., Bahrani, S., Talaei, M., Dianatkhah, M., Sarrafzadegan, N., & Sadeghi, M. (2020). The association between occupational categories and incidence of cardiovascular events: A cohort study in Iranian male population. The International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 11(4), 179.

Huselid, M. A. (2018). The science and practice of workforce analytics: Introduction to the HRM special issue. Human Resource Management, 57(3), 679-684.

Leff, B., DeCherrie, L. V., Montalto, M., & Levine, D. M. (2022). A research agenda for hospital at home.Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 70(4), 1060-1069.

Limbu, Y. B., Pham, L., & Mann, M. (2019). Corporate social responsibility and hospital brand advocacy: Mediating role of trust and patient-hospital identification and moderating role of hospital type.International Journal of Pharmaceutical and Healthcare Marketing, 14(1), 159-174.

Obamiro, K., Jessup, B., Allen, P., Baker-Smith, V., Khanal, S., & Barnett, T. (2022). Considerations for training and workforce development to enhance rural and remote ophthalmology practise in Australia: A scoping review.International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8593.

Peters, M. D., Marnie, C., & Butler, A. (2021). Delivering, funding, and rating safe staffing levels and skills mix in aged care. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 119, 103943.

Poortaghi, S., Shahmari, M., & Ghobadi, A. (2021). Exploring nursing managers’ perceptions of nursing workforce management during the outbreak of COVID-19: A content analysis study.BMC Nursing, 20(1), 1-10.

Silver, J. K., Bean, A. C., Slocum, C., Poorman, J. A., Tenforde, A., Blauwet, C. A., Kirch, R. A., Parekh, R., Amonoo, H. L., Zafonte, R., & Osterbur, D. (2019). Physician workforce disparities and patient care: A narrative review. Health Equity, 3(1), 360-377.

Xu, P., Hu, Y. Y., Yuan, H. Y., Xiang, D. X., Zhou, Y. G., Cave, A. J., & Banh, H. L. (2019). The impact of a training program on clinical pharmacists on pharmacy clinical services in a tertiary hospital in Hunan China.Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 12, 975–980.