Introduction

The property industry has recently experienced the worst slump in the post-war period. Debt outstanding to property companies peaked at £40bn and vacancy rates in the city of London reached 22%. The severity of this slump has stimulated widespread debate among property practitioners and observers over the future structure of the industry. Typically, the discussion has revolved around the theme of whether the industry will return to “normality” once recovery gets underway, or whether a more fundamental restructuring is occurring: Are the current concerns of the industry merely a symptom of the development depression, to be casually shrugged off when the dash for development once again gathers speed? Or has a deeper malaise and confusion settled over the property profession?

The property industry’s vulnerability to the uncertainties of the risk society is closely connected to the rise of the international financial market (Coakley J, 1994). With the emergence of an increasingly complex system of global capital and with the manufacturing industry increasingly reorganised on a worldwide scale, the spatial, temporal context of commercial activity is undergoing rapid transformations.

Flexibility provides the defining logic of these economic shifts. International corporations have to become increasingly sensitive to the fast changing demands of world markets in the accelerated, more competitive environment created by the internationalisation of trade and services. As the commercial strategies of businesses are re-ordered, so their occupational requirements will be similarly remodelled. This will result in a fast-changing demand profile for commercial property. Space requirements are likely to ebb and flow, with the desired floor space, specification and location of new buildings altering dramatically.

This paper aims to study the causes and effects of the recent downturn in the commercial property market in the UK. This is done with the aid of property cycle and business cycle theories. Some analysts believe that the current downturn is likely to be short-lived and that the commercial office and retail property market will bounce back fairly quickly, particularly since the prevailing conditions are very different. His article is very relevant as the buoyancy of the UK property sector is inextricably linked to the health of the UK economy generally.

UK Property Market: An Overview

The UK housing market has a significant impact on the UK economy as almost 78 per cent of households are privately owned.1Homeownership rates are amongst the highest in Europe, and housing is the biggest form of wealth in the UK.

From a construction perspective, the level of new orders within the commercial office sector has never been higher, with occupier demand for space continuing to rise into the third quarter of 2007. This is coupled with the lowest space availability for six years.

The commercial retail sector is another matter, driven as it is by the level of consumer spending and the general state of the economy. Household disposable income and, therefore, expenditure in the UK has been squeezed, resulting in depressed retail sales volumes. Consumer debt levels have never been higher, and the recent credit crunch is likely to restrict future lending, and this will further deter spending. Shopping centre values and returns are under considerable pressure, and a number of retail property sales have failed recently. A huge increase in internet shopping is adding to the traditional retailers’ woes.

The Slump in Property Market

UK house prices slumped in the quarter to December 2007, with London leading the way as momentum gathers towards the 2-year forecast for an average decline of 15% by August 2009. The mortgage banking sector has only just beginning to feel the impact of the housing slump as the number of foreclosures (repossessions) is expected to surge to a record-busting 80,000 for 2008 from 40,000 last year. Northern Rock was the first to go bust; other banks will follow. But in the meantime, watch out for other mortgage lenders, especially those exposed to the buy to let sector such as Paragon, to be pushed towards bankruptcy, down 90% from its highs.

The Big Freeze continues to tighten on the UK commercial property market, with Britain’s fourth-biggest insurer, Friends Provident freezing its Property Fund in December and thereby denying over 110,000 investors the ability to liquidate their investments. The unfolding crash in the commercial real estate market may be the biggest in 27 years as valuations are cut on holdings of the UK’s £700 billion commercial property market. As highlighted periodically over the last six months, funds running short of cash in the wake of investor redemptions will be forced to sell properties and thereby drive down commercial property values in an ever increasing downward spiral. Many funds are following Friends Provident by freezing funds or implementing withdrawal restrictions.

The buy to let sector crash is expected to coincide with the Governments Capital Gains tax changes that come into force in April 2008, which cut the tax rate from 40% to 18%. Typical buy to let produce yields of between 3% and 5% of their current value, and therefore now present a poor investment and incentive to cash in, especially in the light of the trend of several months of declining prices.

UK Housing market has tipped over the edge and is set to track the 2-year forecast trend towards a 15% drop in nominal terms, and in real terms, the decline would equate to more than 20% on the RPI measure.

Distressed sellers seeking the auction route to liquidate in a hurry may find that they have missed the boat in terms of the capacity of the market to meet seller price expectations. The number of properties sold at auction continues to slump from 97% of those bid upon in January 2007 to under 64% at the December Auction at a typical northern auction room.

The Market Oracle affordability index peaked just prior to the start of the decline in UK House Prices. The trend forecast is for a major retracement from extreme levels for the duration of the 2-year forecast to August 2009. Homeowners in the UK are being squeezed by inflationary price rises well beyond the official rate of inflation upon which pay deals are based. Already the Public sector has started organising against the UK governments proposed 3-year pay deals in an attempt to bring future inflation under control.

For nearly a decade, the mantra has been to get onto the property ladder as renting has been viewed as lost money. However, an analysis of the actual costs and benefits suggests that House prices need to rise by more than 2% per annum to match renting over buying. In contrast, the decline in house prices of just 2% per annum would result in a homeowner being £48,000 worse off against renting, on an average £200k property.

Interest rates have clearly peaked with the current rate represented by the 3-month LIBOR falling from an extreme of 6.7% to 5.5%. However, this drop is not a function of the easing of the inter-bank credit crunch but rather as a consequence of central bank action starting 19th December 2007 to flood the money markets with cheap money. Therefore the reduction in interest rates is not expected to have the desired impact on the mortgage sector as banks have tightened lending criteria in the face of growing losses and prospects of an accelerating number of loan defaults going forward.

UK interest rates are on track towards hitting the September 2008 target of 4.75%, by which time the following 12-month trend will become apparent. The next rate cut is scheduled to occur at the 7th February MPC meeting, which is expected to take UK interest rates down by 0.25% to 5.25%.

Thus, the UK Housing market has confirmed its downtrend and is on track towards an average of decline 15% by August 2009.

Property Cycle

A property market endures significant cyclical movements and volatility. These property cycles have been subject to extensive research during the past decades. To a certain extent, publications about these cycles are also cyclical. In the 1990s, the late 1980s property boom caused a rise in publications. The last commercial property boom, which culminated around 2000, now appears in literature. The fast amount of literature shows that property cycles for a different type of property vary in their manifestation. They vary in amplitude, periodicity and impact on the wider economy (Wheaton 1999; Leung 2004; Grenadier 1995). These fluctuations are found in all property market indicators, which reflect an underlying cyclical dynamic.

According to Ball et al. (1998), for the commercial property markets, these dynamics come from the user market, the development market, rental cycles, and capital value and return cycles. In their analysis of the commercial property market, Ball et al. (1998) make a distinction between short and long cycles. Long cycles are cycles of 20-30 years or longer and are usually called Kuznets cycles. We will focus on the short cycles of 9-10 years (or shorter), which are associated with business cycles.

The simplest explanation of cycles in commercial property is that they are part of the general business cycle. Cyclical fluctuations in the output of the economy bring about similar fluctuations in demand for commercial property. The problem with this explanation is that fluctuations in user demand do not explain fluctuations in development. For instance, for offices, a pattern of periodic over- and underbuilding has been found. These instabilities and oscillations have also been explained by the durability of property and the lag between demand and supply. These characteristics1, but also to institutional features of the market itself, produce an endogenous mechanism that generates the cyclical tendencies in property development.

According to Ball et al. (1998), these cycles are independent of fluctuations in demand. The endogenous mechanism does not always take into account key property market variables such as rents, yields, building costs or the supply of capital, nor the behaviour of agents. Because agents are uninformed about these variables and show myopic behaviour, they make systematic errors about future market conditions, which in the end, results in cyclic behaviour.

The explanation for cycles in the housing market is, to some extent, similar. An important portion of the housing cycles is related to the business cycles and has been documented for several countries. Another explanation for housing price cyclicality and volatility is the structure of the residential lending market. Also, the lag between demand and supply and myopic behaviour is mentioned. Due to these development lags and the behaviour of landowners, building contractors and developers, fine-tuning problems can arise so that severe short-term price mutations may occur. Poterba (1984) was one of the first authors who mention this cycle when he introduced the asset market approach.

Dipasquale and Wheaton (1994) are critical of the asset market approach, which was developed with the aim of estimating investment levels. They point out that this approach implies that a rise in house prices will lead to a permanent rise in the number of newly-built homes. The stock-flow model proposed by Dispasquale and Wheaton implicitly assume the existence of an equilibrium between the number of households and the housing stock; hence, at the regional level, the number of households determines a priori the new housing supply. They show that the supply changes due to a gradual increase in new housing construction and declines slowly due to e.g. demolition or fire. In this approach, the new building is dependent on exogenous factors and the house price. Exogenous factors on the supply side include building costs and interest rates.

Why was there a Boom?

Identifying the cause of rapid rises in house prices is crucial for policymakers. Fast growth in housing wealth increases consumption, aggregate demand and future inflation. If recognised as a speculative boom, this would signal appropriate intervention (increasing the Repo rate) by the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) to avoid the potential slowdown when the price bubble bursts. On the other hand, increases in house prices, justified by changes in expectations about fundamentals, do not require intervention since this would result in a misallocation of resources.

A problem facing the MPC is the difficulty in identifying the difference between speculative bubbles and changing expectations about fundamentals. With three apparent house price bubbles (positive deviations from fundamental value) in the UK during the last 40 years (the early 1970s, late 1980s and early 2000s), this is a highly topical issue with important policy implications.

Household consumption is an important expenditure component of real Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and the relationship between real house price inflation and consumption growth has been frequently examined in the literature. Case et al. (2001) use data for 14 countries and report a large effect of housing wealth on household consumption, whereas the evidence of a stock market wealth effect is relatively weak. Helbling and Terrones (2003) suggested that a burst in a housing bubble is also important.

These authors conclude that real private consumption, real private gross fixed capital formation in machinery and equipment and real private investment in construction all experienced larger and faster declines in their growth rates following a housing price bust than a stock market bust.

At the microeconomic level, investigations by Campbell and Cocco (2004) suggest the response of household consumption to house prices is largest for older homeowners and smallest for younger renters. They also report that regional house prices affect regional consumption growth. Structural changes in the economy, such as financial liberalisation, also seem to have an impact. Muellbauer and Murphy (1997) show that relaxed borrowing constraints appear to drive up house prices and stimulate consumption.

Fundamental values for house prices are frequently measured by comparing house prices to rents or disposable income, where deviation from the long term average of these relations suggests housing. Other studies compare house prices to the ‘affordability’ concept in terms of fundamental values based on real wages and employment, real construction costs and real interest rates (Abraham and Hendershott, 1996; Bourassa et al., 2001).

The Central London office markets have reached the trough of their fourth major market cycle of the post-war period. The current cycle, like that of the late 1980s/early 1990s, has been a global phenomenon, and across Europe, a synchronised cycle of office take-up, vacancy, rental growth and building has affected most markets with varying degrees of severity. It is, therefore, a good time to take stock of our understanding of how these cycles are generated and where theory needs to be improved in the light of recent experience. After each property boom and bust, the same two questions are always asked, ‘why did it go wrong?’ and ‘how can we avoid it happening again?’ The answers are also broadly the same each time – it went wrong because of inaccurate data, incorrect

Forecasts and inadequate analysis by developers and investors; the solution is to improve all of these for next time. Following the global boom-bust cycle of the late 1980s/early 1990s, there has been a huge investment of resources into property data-gathering, forecasting techniques and investment analysis. This has taken place against a background of economic theory increasingly dominated by the new orthodoxy of ‘rational expectations.’ In its most extreme form, this puts the blame for property cycles on market agents forming ‘myopic’ expectations about future prices, typically assuming that the future will be like the present or the past.

The argument goes on to say that if agents exercise perfect foresight, cyclical fluctuations cannot be generated endogenously; rather they can only be the product of repeated exogenous shocks, the outcomes of which can be predicted even if their timing cannot. This then tends to shift attention to the search for external scapegoats, whether ill-judged government intervention or acts of God.

However, what does perfect foresight mean in the property market? As summarised by Wheaton (1999, p. 215), it means that developers and investors ‘perfectly understand the equations that govern market behaviour and can thus make correct forecasts of rents’. To someone like the author, who has spent his whole professional life repeating the mantra that in an imperfect world, ‘all forecasts are wrong,’ this is indeed startling.

Boom to Slump

The boom took a sharp turn because, as property analysts at the investment bank Morgan Stanley warned that the world’s largest banks could have about $212bn (£110bn) of assets at risk of default as a result of the global contraction in the commercial property market and the slump in prices.

While expectations grow that the residential market is about to go into decline, investors in the commercial property sector have already started to march swiftly out of the exit door, bringing trouble in their wake.

Morgan Stanley estimated recently that based on its revised estimates of capital growth values, big property groups such as British Land, Hammerson and Land Securities were nearly one-third overvalued on recent share prices.

Fears of a real crash have been heightened by the reappearance of three property veterans raising up to £200m in a stock market listing to cash in on a slump. Raymond Mould, Patrick Vaughan and Humphrey Price, who founded and sold Pillar Property to British Land for £811m in 2005, have set up London & Stamford Property and are on the prowl for distressed assets.

With UK commercial property achieving total returns approaching 20% over each of the previous three years, 2007 began optimistically with the UK industry’s consensus forecast anticipating low double-digit returns. The first six months of 2007 confirmed this as the upward trend of previous years continued, albeit at a slower pace. Debt buyers were all but shut out of the market as the weight of money from institutional investors, overseas buyers, and retail funds sustained unprecedented high prices and values. Growth, however, began to moderate against a backdrop of mounting inflationary pressure and expectations of higher interest rates.

At the same time, the newly launched UK REIT market (Jan ‘07) witnessed strong negative sentiment that became a catalyst to an exodus from the sector. Share prices began sliding as the underlying assets continued to rise, and significant discounts to NAV started to emerge in REIT share prices. Cracks began to appear over the summer as investment transactions failed to complete, and property valuation yields, particularly in secondary properties, began to rise.

The onset of the credit crunch in the second quarter of 2007 confirmed the poorer sentiment across all property sectors; investors increasingly withdrew from the property market, open-ended property funds suffered net redemptions that exceeded their ability to sell property assets, and published property valuations began falling month-on-month

Future of Property Market

How stretched is the UK housing market? Given how long UK house prices, especially those in London, have defied both gravity and conventional models of valuation, a confident answer to that question is hardly possible. A look at a couple of the conventional “affordability” measures suggests house prices are more likely to fall sharply than to rise steeply.

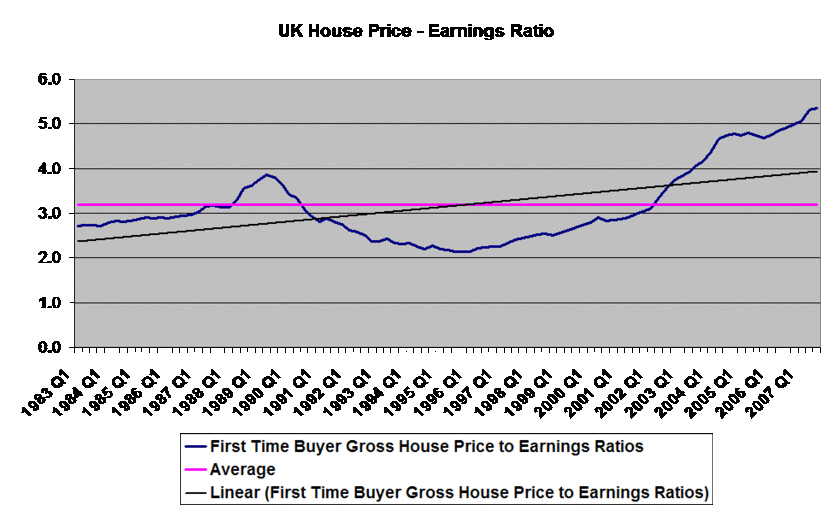

Exhibit 1 is a measure of average UK house prices to average earnings. The specific measure is Nationwide’s ‘First-time buyer gross house price to (annual) earnings ratio’. As shown in Chart 1, the current value of this ratio, 5.3, is the highest since 1983 (in fact since records began), easily exceeding the 3.9 reached during the previous housing bubble in Q2 1989. The average value over the period shown in Figure 1 is 3.2. If we fit a simple linear trend over the period, the most recent value of the (rising) trend line would be just under 4.0.

There is no logical reason for the house price to earnings ratio to revert to either its historical average value or to its trend value. Even if we believed that a reversal to trend, say, was inevitable, this would not tell us whether this would happen through a decline in house prices, through a rise in earnings or possibly even through a further increase in house prices swamped by an explosion in earnings growth. Earnings growth has been much more stable, however, than house price inflation.

So let’s assume earnings will continue to grow at, say, 4.5 per cent per annum. To restore the house price to earnings ratio to its historical average of 3.2 over a two-year period would require almost a 19 per cent annual decline in house prices (for each of these two years). If the restoration of the historical average ratio were to take three years, the annual rate of decline of house prices would be just under 12 per cent.

If the house price to earnings ratio reverted not to its historical average but to its 2007 Q2 trend value of 4.0, the annual rate of decline of house prices would be around nine per cent if the 4.0 value for the ratio were to be reached in two years, and about five per cent if it were to take three years.

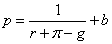

A finance perspective sees the value of a house as the present discounted value of current and future rental earnings, actual or imputed, derived from the ownership of the house. With a bit of hand waving, this produces the following expression for the ratio of the current house price to the current rentals (actual or imputed) from housing:

where p is the current house price – rental ratio, r is the long-run risk-free interest rate, π is the long-run average risk premium on housing equity, and g is the long-run expected growth rate of housing rentals. Finally, b is the value of the housing bubble (if there is one). The first term on the right-hand side is, therefore, the ‘fundamental value’ of the price-to-rental ratio.

Market measures of the long-term risk-free real rate of interest for the UK continue to be low, partly because of continuing anomalies in demand for long-dated index-linked gilts by pension funds and partly because of the inexplicable failure of the UK authorities (and other public agencies) to issue more of the stuff. There can be little doubt, however, that the real risk-free rate is rising globally and also in the UK. The decline in the real long-term risk-free rate of the early years of this century no doubt accounted for part of the increase in the fundamental value of UK property.

The future expected growth of actual or imputed rental income from housing, therefore, must carry quite a bit of the weight in any rationalisation in terms of fundamentals of the past and present strength of UK house prices. A limited supply of new residential housing (due in part to planning and zoning restrictions) other than in parts of the buy-to-let market and relatively housing-friendly demographics were sources of housing price strength. With suitable land in highly inelastic supply and real incomes rising, rents could well grow faster than earnings almost indefinitely.

The fact that prices in part of the UK housing market are strongly influenced by global fads, fashions and other factors is good news for UK homeowners when the UK economy is about to slow down significantly, as it is now. It is, however, also a potential source of vulnerability. Fads and fashions change. Tax-averse expatriates may be footloose and may consider a move to Paris, New York or Dubai when their non-domiciled tax status in the UK is threatened. Hence, we consider a significant decline in UK house prices, say by thirty per cent or so over two or three years, to be likely but not inevitable.

Conclusion

A decline in house price does not, on average, make UK residents worse off. It merely redistributes wealth from those long in housing to those short in housing: the representative UK household will lose as homeowners but will gain the same amount in present discounted value terms, either as renters or through the opportunity cost of the imputed cost of renting saved by owner-occupiers. Typically, the middle-aged and the old who have not yet traded down will lose. The young and all those expecting to trade up will gain. Since housing prices in the UK have become exorbitantly high and an increasingly large contingent of first-time would be buyers is priced out of the housing market at current prices, a significant decline in house prices would, on balance, be welcome.

There are two downsides to this scenario, in addition to the losses suffered by those long housing. The first is that if the decline in house prices reflects the bursting of a bubble (a decline in b in the formula) rather than a decline in the fundamental value of the residential property, there will be a net negative wealth effect because there will be no consumers of housing services to benefit when the value of the housing stock declines.

This negative wealth effect could be macroeconomically significant. Second, even if there is no net wealth effect from a decline in house price, there will be a liquidity or collateral effect. Residential property is mortgageable. It acts as security for consumption loans (through mortgage equity withdrawal) that would not be forthcoming if they had to be provided on an unsecured basis. When this source of collateral shrinks, consumer borrowing will decline, and consumer spending is likely to decline with it.

These detrimental effects from a decline in the price of residential property are, however, likely to be transient – cyclical at most. The social benefits from a significant decline in UK house prices are bound to be significantly larger than the social costs associated with any short-term credit squeeze on consumers it may cause or aggravate.

Reference

Ball, M., Lizieri, C., and MacGregor, B. D. (1998). The economics of commercial property markets. Routledge, London and New York.

Ball, M. (1998). Institutions in British Property Research: A Review. Urban Studies, 35(9), 1501-1517.

Wheaton, W. C. (1999). Real Estate “Cycles: Some Fundmantals. Real Estate Economics, 27(2), 209-230.

Abraham, Jesse M. and Patric H. Hendershott. Bubbles in Metropolitan Housing Markets. Journal of Housing Research, 7(2), 1996, pp. 191-208.

Muellbauer, J & Murphy, A, 1996. “Booms and Busts in the UK Housing Market,” Economics Papers 125, Economics Group, Nuffield College, University of Oxford.

John Campbell & Joao Cocco, 2004. “How Do House Prices Affect Consumption? Evidence from Micro Data,” 2004 Meeting Papers 357a, Society for Economic Dynamics.

Helbling, T. and M. Terrones. 2003. When Bubbles Burst. IMF World Economic Outlook: 61–94.

DiPasquale, Denise, and William Wheaton. Urban Economics and Real Estate Markets. Prentice Hall, 1994.

Poterba, J., 1984. Tax Subsidies to Owner-Occupied Housing: An Asset-Market Approach.