Introduction

As construction companies increasingly understand the importance of multiculturalism in the workplace, diversity has become an important concept of management. According to Gröschl and Bendl (2015), a diverse workforce is comprised of people with distinct or dissimilar characteristics. Usually, the concept of diversity involves the creation of a working environment characterised by the presence of people from different backgrounds.

Their varying characteristics may be in form of gender, race, religion, sexual orientation and education (among other socioeconomic variables) (Andrevski et al. 2014; Cumming, Leung & Rui 2015). Based on the view that diversity is a source of strength, United Kingdom (UK) construction firms are beginning to recognise the need to have people from different backgrounds work in their teams (Joyce 2016). Consequently, they benefit from good diversity management practices through improved reputation and operational performance (Bohnet 2016).

This study investigates the above issue through a review of gender representation in the UK construction industry. This sector is chosen for this analysis because of its significant contribution to the UK’s gross domestic product (GDP). A report by Joyce (2016) suggests that the industry contributes about £64 billion to the economy. The UK construction sector also provides employment to about 2.2 million citizens, meaning that it plays a pivotal role in maintaining the country’s social makeup (Joyce 2016).

Despite the important role of this sector in supporting livelihoods in the UK, it is surprising that it has the worst record in gender diversity not only in the UK but also in Europe (Leung, Chan & Cooper 2015). This paper explains the underrepresentation of women in the sector and why the problem should be tackled urgently. At the end of this paper, a set of recommendations will be provided to address the issue.

Explanation of Underrepresentation

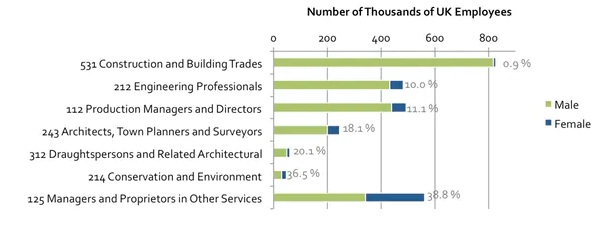

According to the Planning, BIM and Construction (2019), one in five construction companies in the UK have no female representation at the management level. Consequently, it is reported that only 1% of the 800,000 employees who work in the UK construction industry are women (Planning, BIM and Construction 2019). The percentage of female representation increases to 18% if the analysis is widened to include industries associated with construction, such as surveying, architecture and planning, (Loosemore & Higgon 2015). These statistics are further broken down in figure 1 below, which shows that women barely occupy 40% of any subsector of the UK construction industry.

Figure 1 above shows that management and proprietorship services in the UK construction industry have the highest percentage of female representation (38.8%), while the least representation is observed in the construction and building trades sectors (0.9%) (Leung, Chan & Cooper 2015). These statistics underscore the imbalanced representation of male and female participation in the industry.

The gender gap between male and female workers in the UK construction industry has been partly equated to the presence of prejudices against women that exist in the sector (Leung, Chan & Cooper 2015). It is also reported that about half of all professionals in the industry claim they have never worked with a female manager in their profession (Leung, Chan & Cooper 2015). Statistics describing the composition of male and female involvement on-site construction work are even more surprising because reports show that up to 99% of women in this subsector are male (Du Plessis, O’Sullivan & Rentschler 2014).

This statistic is ironic to the acknowledged positive role played by women in the industry because it is estimated that up to 93% of employees in this sector do not feel threatened by female leadership (Du Plessis, O’Sullivan & Rentschler 2014). In fact, it is reported that some of them believe that having a woman as a leader is a positive thing (Dezsö, Ross & Uribe 2016; Opstrup & Villadsen 2015; Post & Byron 2015).

A different independent report prepared by the Planning, BIM and Construction (2019) after analyzing the gender composition of 399 boards of construction companies in the UK, showed that only 22% of the members were comprised of women. A deeper assessment of the statistics shows that 16% of the boards had no female representation (Du Plessis, O’Sullivan & Rentschler 2014). The low representation of women on the boards of UK construction firms has made some observers fearful that the industry could be eroding the gains made in gender representation across multiple economic sectors in the UK (Triana, Miller & Trzebiatowski 2014). Consequently, it is unsurprising that about half of all construction workers in the UK report never having worked with a female manager (Du Plessis, O’Sullivan & Rentschler 2014).

The lack of gender diversity in the UK construction sector has been partly explained by reports which suggest that about 48% of women in the industry have experienced some type of sexual discrimination at work (Joyce 2016). The most common behaviour is the use of inappropriate comments to describe women’s work. This observation signifies the presence of wrong attitudes towards equality and diversity in the UK construction industry (Murray & Dainty 2014). Part of the problem has been traced to the failure of existing companies to modernise their human resource practices (Ranstard 2019). In other words, they are deemed resistant to change.

The construction industry poses unique challenges to women because of wrong attitudes about female leadership. The lack of adequate resources for adopting progressive recruitment practices and negative social perceptions about the role of women in the workplace have further worsened the problem (Murray & Dainty 2014). Nonetheless, one of the main challenges that impede female participation in the industry is the risk of injury (Joyce 2016).

This issue makes women more vulnerable to injury compared to their male counterparts because of the perception that they are the “weaker sex.” Furthermore, many construction safety equipments are designed with the assumption that men are the main users. Therefore, in addition to the perceived physical weakness of women in the workplace, they suffer a higher risk of injury compared to their male colleagues.

The low level of gender diversity in the UK construction industry has created a wide pay gap between men and women. According to Owen (2019), women earn about 95% of what their male counterparts do. The statistics are deemed to be worse for women who come from minority groups because they only make 81% of what their male counterparts do for the same work (Planning, BIM and Construction 2019). This problem is worsened by the lack of proper female mentorship programs in the industry because few women have had a lasting impact on the sector. Therefore, upcoming female professionals lack the guidance that their male counterparts have enjoyed for decades from those who came before them.

Why Underrepresentation is an Issue of Concern

Although many organisations understand the importance of diversity, few of them make it a priority in their business case development projects (Byrd & Scott 2014). The problem is partly caused by the desire to address “other” business considerations that have a direct impact on return on investments. This management approach is detrimental to the vision of having a dynamic workforce because shareholder maximisation interests often supersede those of diversity management. Most human resource departments overlook this fact and formulate policies that promote diversity, hoping that management would support such initiatives (Rabl et al. 2014).

However, such initiatives fail because they are focused on supporting predictable corporate practices that have a high potential for profits (Cooper, Patel & Thatcher 2014). This strategy makes underrepresentation a big problem for most organisations.

As highlighted in this paper, the underrepresentation of women in the UK construction industry is deemed to be the worst of any sector in the country. Furthermore, according to Balfour Beatty PLC (2019), the UK’s performance, in terms of gender balance, is the worst in the European Union (EU). These statistics are a major cause of concern because they overlook female talent. The exclusion of women in social conversations and the board composition of construction companies also create a toxic culture that undermines team work because of the difficulty in creating synergies in such environments (Roberson, Holmes & Perry 2017).

The unconscious bias and ignorance about female leadership in the construction industry also portends serious negative ramifications on the industry by breeding contempt among male workers regarding female competence in leadership.

The lack of balanced representation between men and women may also be problematic for organisations that want to build cohesive teams because it builds mistrust between male and female colleagues. Furthermore, some female workers may hesitate to give their views regarding certain industry actions because of the fear of being misjudged, abused or undermined. Therefore, they may choose to withhold their views even though they may be beneficial to the overall development of a project (Mir & Pinnington 2014). Such an outcome erodes the quality of decisions made in the workplace (Zhang & Qu 2016). Therefore, the failure to include more women in the workforce may create an incompetent team that fails to analyse issues through logic and instead support a patriarchal model of decision-making that may be subject to bias.

The lack of diversity in the UK construction industry could be problematic to the future sustainability of the sector by limiting its potential to adapt to changing dynamics in the labour market. For example, companies that do not promote diversity may lose their competitive edges to those that can demonstrate the applicability of this concept in their corporate practices (Mir & Pinnington 2014). The failure to apply progressive diversity management practices may also limit the uniqueness of thought that women bring to corporate boards, thereby undermining the quality of decisions made. Companies that are resistant to this type of change are also linked to poor financial performance and low levels of innovation (Yeazdanshenas 2014).

The UK construction industry could suffer from the same problem because a male-dominated sector means there is little room for alternative inputs or thoughts. In this regard, these companies are not able to leverage diversity for optimal corporate performance. By failing to accommodate perspectives on female leadership in their decision-making processes, most construction firms may suffer from the inability of managers to evaluate information accurately and comprehensively.

Conclusion

Although this study has highlighted the depth of female underrepresentation in the UK construction industry, it is important to contextualise this problem as one that affects most fields or industries that demand intense technical skills. For example, other sectors that have a poor gender diversity profile include the sciences and tech-industries (Sonja 2014). Although progress towards gender balance remains problematic and slow, there is hope that the future would see more female representation in some of these male-dominated fields. However, to accomplish this goal, there is a need to adopt more progressive recruitment policies and initiative attitude changes in the industry as explained below.

Recommendations

There is a need to introduce new regulations in the construction industry that would see equality taken more seriously in the workplace. This recommendation emanates from the view that it is more difficult to implement an attitude change than formulate a policy to guide human behaviour in this industry. The potential to realise a gender balanced composition of workers in the construction industry is not far-fetched because six construction firms in the UK have managed to achieve this objective. These companies are either led by women or have an equal number of gender representations in their boards.

For example, Renishaw PLC has more women (70%) sitting on its board compared to men (Planning, BIM and Construction 2019). Therefore, as part of the solution to addressing the gender divide in the industry, the public should be sensitised about the problem, as done by the management of Renishaw Company (Planning, BIM and Construction 2019). They move across schools and universities in the UK trying to increase the interest of young women about the construction industry and how to address the gender divide that exists in it.

There also needs to be a more collaborative effort among all stakeholders in the construction industry to address the gender gap because everybody needs to be involved in the process of overcoming stereotypes that have consistently barred women from ascending to high levels of management (Galea, Powell & Loosemore 2015). For example, human resource agencies need to be involved in the process to provide professional guidelines on how to achieve gender diversity. Already, some human resource departments have made attempts to advise some companies on how to realise this outcome, as observed in the report authored by the Planning, BIM and Construction (2019). Similarly, the multinational human resource agency, Ranstard (2019) has made significant progress in this regard.

Lastly, there is a need to change people’s perception of female leadership and involvement in the construction industry because the negative attitude held by the general populace that the industry is a male-oriented one is fuelling the problem. For example, the report by Planning, BIM and Construction (2019) showed that only 13% of women in the UK would consider pursuing a career in the construction industry.

This problem stems from the misconception that the jobs available in the industry are physically demanding and that women cannot compete with their male counterparts. However, this is not always the case because there are many other roles available for women in the industry, such as procurement, surveying, health and safety that can be done by women. However, few people are aware of these opportunities. Therefore, they need to be sensitised about them. Collectively, these efforts would improve gender diversity in the industry.

Reference List

Andrevski, G, Richard, OC, Shaw, JD & Ferrier, WJ 2014, ‘Racial diversity and firm performance: the mediating role of competitive intensity’, Journal of Management, vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 820-844.

Balfour Beatty PLC 2019, Inspiring change: attracting women into construction. Web.

Bohnet, I 2016, What works, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Byrd, MY & Scott, CL 2014, Diversity in the workforce: current issues and emerging trends, Routledge, London.

Cooper, D, Patel, PC & Thatcher, SM 2014, ‘It depends: environmental context and the effects of faultlines on top management team performance’, Organization Science, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 633-652.

Cumming, D, Leung, TY & Rui, O 2015, ‘Gender diversity and securities fraud’, Academy of Management Journal, vol. 58, no. 1, pp. 1572-1593.

Dezsö, CL, Ross, DG & Uribe, J 2016, ‘Is there an implicit quota on women in top management? A large-sample statistical analysis’, Strategic Management Journal, vol. 37, no. 1, pp. 98-115.

Du Plessis, J, O’Sullivan, J & Rentschler, R 2014, ‘Multiple layers of gender diversity on corporate boards: to force or not to force’, Deakin Law Review, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 1-10.

Galea, N, Powell, A & Loosemore, M 2015, ‘Designing robust and revisable policies for gender equality: lessons from the Australian construction industry’, Construction Management and Economics, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 375-389.

Gröschl, S & Bendl, R 2015, Managing religious diversity in the workplace: examples from around the world, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., New York.

Joyce, R 2016, How far have women progressed in the UK construction industry. Web.

Leung, M, Chan, IY & Cooper, C 2015, Stress management in the construction industry, John Wiley & Sons, London.

Loosemore, M & Higgon, D 2015, Social enterprise in the construction industry: building better communities, Routledge, London.

Mir, FA & Pinnington, AH 2014, ‘Exploring the value of project management: linking project management performance and project success’, International Journal of Project Management, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 202-217.

Murray, M & Dainty, A (eds) 2014, Corporate social responsibility in the construction industry, Routledge, London.

Opstrup, N & Villadsen, AR 2015, ‘The right mix? Gender diversity in top management teams and financial performance’, Public Administration Review, vol. 75, no. 1, pp. 291-301.

Owen, A 2019, Demolishing gender imbalance in the UK Construction industry. Web.

Planning, BIM and Construction 2019, What can construction companies do to improve gender equality. Web.

Post, C & Byron, K 2015, ‘Women on boards and firm financial performance: a meta-analysis’, Academy of Management Journal, vol. 58, no. pp. 1546-1571.

Rabl, T, Jayasinghe, M, Gerhart, B & Kühlmann, TM 2014, ‘A meta-analysis of country differences in the high-performance work system-business performance relationship: the roles of national culture and managerial discretion’, Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 99, no. 1, pp. 1011-1041.

Ranstard 2019, Women in the construction industry. Web.

Roberson, Q, Holmes, O & Perry, JL 2017, ‘Transforming research on diversity and firm performance: a dynamic capabilities perspective’, Academy of Management Annals, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 189-216.

Sonja, B 2014, Women in IT in the new social era: a critical evidence-based review of gender inequality and the potential for change, IGI Global, New York, NY.

Triana, MC, Miller, TL & Trzebiatowski, TM 2014, ‘The double-edged nature of board gender diversity: diversity, firm performance, and the power of women directors as predictors of strategic change’, Organization Science, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 609-632.

Yeazdanshenas, M 2014, ‘Designing a conceptual framework for organizational entrepreneurship in the public sector in Iran’, Iranian Journal of Management Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 365-390.

Zhang, Y & Qu, H 2016, ‘The impact of CEO succession with gender change on firm performance and successor early departure: evidence from China’s publicly listed companies in 1997–2010’, Academy of Management Journal, vol. 59, no. 1, pp. 1845-1868.