Abstract

In focusing on determining the impacts of age diversity on the organisational performance of the Coca-Cola Company in the Birmingham area, Alabama, United States, this paper found that the company has adopted diversity and inclusion policies that focus on creating a considerate working environment characterised by the absence of any kind of discrimination. It became apparent that age diversity is a major element of this policy, and Coca-Cola strives to ensure that there is no discrimination against any particular age groups in its workforce.

The paper focused on highlighting that human resources managers at Coca-Cola are concerned about the success of the company’s diversity measures and consistently work towards meeting the needs of individual generational groups of employees. The paper highlighted the skills required to promote diversity, the impacts of prejudice and biases on diversity management, and the ways in which HR managers at Coca-Cola promote better communication among age-diverse workforce.

In terms of methodology, the research adopted the inductive and qualitative approaches in gathering and analysing data that was collected by personal interview with the respondents. The sample population comprised of 30 employees from diverse generations and five human resources managers who work with Coca-Cola.

It became apparent from the respondents’ responses that they were fully aware of the complexities arising from increasing age diversity among the employees of the Coca-Cola Company. It became known from the literature review that issues in the context of age diversity in organisations emerge primarily because of some generalised perceptions that have traditionally characterised the social structure of organisations. However, the focus of the Coca-Cola management is on negotiating and finding positive solutions among employees of different age groups. The main conclusion was that Coca-Cola has adopted diversity and inclusion policies that focus on creating a caring work environment characterised by the absence of any kind of discrimination.

Table of Contents

- Declaration

- Acknowledgement

- Abstract

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Background

- Research Problem/Rationale

- Research Aim and Objectives

- Research Questions

- Literature Review

- The Concept of Age Diversity and Diversity Management

- Emergence of Age Discrimination in Organisations

- Age Diversity and Employee Behaviour

- Negative Age Discrimination

- Suggested Solutions to Age Diversity Issues

- Gaps in Available Research and Frameworks

- Conceptual Framework

- Research Design and Methodology

- Research Philosophy – Selection and Use

- Discussion and Rationale for the Selected Research Approach

- Research Design

- Method of Data Collection

- Gaining Access to Data

- Study Population and Sample

- Research Context

- Questionnaire

- Limitations and Ethical Considerations

- Data Analysis

- Results

- Analysis and Discussion

- Conclusions and Recommendations

- Conclusions

- Recommendations

- Reference List

- Appendix I

- Appendix II

Introduction

Demographic changes within recent decades and the consequent changes in the age composition of workforce have led to major concerns about the impacts that the rapidly increasing percentage of older employees will have on organisational productivity and adoption of fair policies in dealing with employees of different age groups. It has now become increasingly important for organisations to find different ways of becoming inclusive, as diversity enhances the organisational potential in attaining competitive advantage and higher productivity in the rapidly increasing competitive and globalised environment.

Age diversity in the organisational environment is related to the presence of workers of different age groups and is used as a concept to illustrate the overall composition of workforce in an organisation. Age diversity can be regarded from the perspective of systems through which people classify themselves into specific demographic groups characterised by the same age as they are. Consequently, employees distinguish themselves by having qualities, abilities, and traits that are different from those of the people of other age groups.

In effect, age diversity is a demographic characteristic that is related to distinct characteristics of people of specific age groups and is much relevant in the organisational context because it contributes to finding ways of making the best use of group dynamism relative to occupational functions, seniority, and rewards (Shin & Park 2013).

Background

The Coca-Cola Company is very vocal about its Sustainability and Workplace Policies. It has demonstrated actions that are in-line with the claim. The company has one of the oldest Board of Directors among its peers, who have been chosen based on their experience (Coca-Cola SEC 2016). As a beverages company, that needs to recruit teen consumers, apart from its marketing push, the company has in the recent past, also focussed on listening to the voice of millennial employees (Coca-Cola 2016). Globalisation and the relaxation of labour laws have led to enhanced mobility of workers migrating from one country to another.

Consequently, the labour force in the majority of multinational corporations comprises individuals from diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds, races, sexualities, levels of expertise, age, and gender. According to Carol & June (2015), globalisation has put an end to the epoch of people working in a blinkered environment.

For organisations, to be competitive in the current environment is pertinent in terms of having a diverse workforce. Human resources managers should embrace, appreciate, value, and identify with the disparities among employees based on age, ethnicity, race, and gender. Carol and June (2015, p. 34) define diversity as “the differences among employees concerning race, gender, personality, age group, cognitive style, tenure, organisational functions, and education.” This entails how individuals view themselves and their colleagues, which in turn influences their relationships.

An organisation with a diverse workforce should ensure that it has efficient communication strategies in place. It would be difficult for the workforce to adopt or embrace changes without adequate communication.

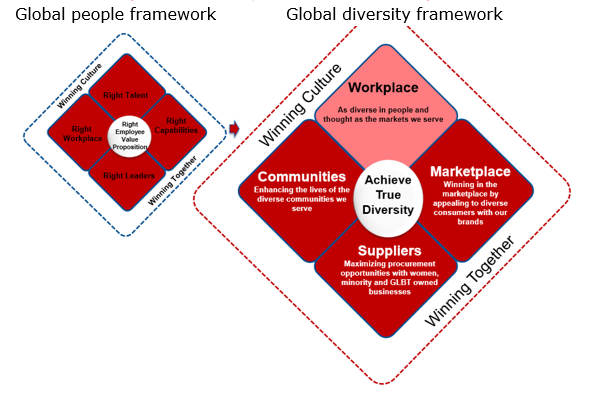

Given that diversity is bound to rise in the coming years, it becomes pertinent for organisations to provide resources and invest in diversity management. The Coca-Cola Company appreciates the significance of diversity to its growth, which is why the company has invested in employees from diverse age groups. The company’s workforce comprises individuals from different generations. A blend of employees from diverse age groups boosts the company’s performance. Apart from pure academic interest, this study is also of interest to corporations in general and human resources managers, who have interest in the area of impact of age diversity on organisations.

Research Problem/Rationale

The Coca-Cola Company is a renowned multinational corporation that specialises in the production of a variety of beverages. It is among the biggest companies not only in the United States but also across the globe. The company has a diverse workforce, and despite the numerous challenges attributed to employee diversity, it has managed to retain a motivated labour force. Many human resources managers are unable to maintain a diverse workforce due to biases and cultural prejudices. Previously, human resources managers adopted best practices that worked across the organisations.

Today, the managers appreciate the importance of adopting customised practices. Carol & June (2015, p. 42) argued that “[d]iversity requirements are contingent upon a range of organisational idiosyncrasies.” Therefore, companies require adopting diversity management techniques that suit their needs. However, most of studies on the topic have not evaluated the significance of recruiting an age diverse workforce. In addition, a significant gap continues to exist between theories and practices of dealing with employees from different generations. Besides, most studies view diversity in the context of cultural differences.

They fail to appreciate the importance of diversity in terms of disparities among individual employees. This paper seeks to highlight that human resources managers need to consider the needs of an individual generational group of employees to realise the success of diversity. The rationale for this paper is to evaluate the contribution of age diversity to the success of the Coca-Cola Company. The importance of such diversity, in relation to the holistic development, which encompasses, human resource practices, marketing, and brand image of the organisation in general and the Coca-Cola Company in particular are the key areas of interest.

Research Aim and Objectives

The purpose of this study is to assess the contribution of age diversity to the success of the Coca-Cola Company as a global organisation with focus on the Birmingham, Alabama. The contemporary workplace characterised by rapid globalisation and increasing competition requires a labour force that can bring different worldviews, experiences, and variety of strengths. Organisations can realise this goal by hiring employees from diverse age groups.

Apart from pooling different strengths and experiences, a diverse workforce ensures that a corporation does not incur excessive costs due to employee turnover. Every employee has unique talent, and therefore, there is the need to have a working atmosphere that caters to the needs of all workers. The human resources managers should be aware of all the skills necessary for managing a diverse workforce.

The following objectives have been identified:

- To determine the contribution of age diversity at the Coca-Cola Company.

- To determine the skills and experiences that a diverse workforce brings to the company.

- To determine the key organisational performance areas at the company.

- To determine the strategies that the Coca-Cola Company utilises to promote diversity.

- To provide recommendations for effective use of age diversity to improve business performance.

Research Questions

The research questions that guide this study include:

- What policies and practices promote age diversity at organisations?

- What are the effects of prejudices and biases on diversity management and organisational success?

- How do human resources managers address the needs of diverse generational groups in a diverse workforce?

- What strategies do organisations use to guarantee that employees from different generational groups work together?

- How do human resources managers promote communication among associates from diverse age groups?

Literature Review

A vast body of literature is available on the existing status of age diversity and ways through which issues arising from this diversity, be addressed effectively. It is known that most of the studies on diversity management are based on Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory. They explore diversity from a cultural perspective. However, most of the studies fail to appreciate that diversity may arise due to other social factors, such as education, age, disability, and technological development. This study will bridge this gap by analysing how the Coca-Cola Company derives its success from hiring a workforce comprising individuals from diverse age groups.

The Concept of Age Diversity and Diversity Management

It was not until the 1960s and 1970s that the USA recognised the need for workplace diversity. It was under President John F. Kennedy, in 1961 that the United States, established the President’s Committee on Equal Employment Prospect. The key objective of the Executive Order, thus passed, was to study, identify, and help remove any discriminatory practices in the Unites States government services (The American presidency project 1961).

Later, under President Lyndon Baines Johnson, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 helped strengthen the foundation laid by President Kennedy, by avoiding discrimination in any activity (Library of congress 1964). In 1971, President Nixon’s administration, further strengthened the initiatives.

The concept of diversity management has been further probed by researchers (Jenner 1994, Nkomo & Cox 1996). These researchers, while examining the diversity concept, more in terms of cultural diversity, talk about the importance of managing diverse needs of the individuals. Most of the available literature from the 1970 to late 1990s, lack specific focus on age related diversity. It is only in later papers, that we find some specific mention of age diversity.

Emergence of Age Discrimination in Organisations

Kunze, Boehm, & Bruch (2011) have highlighted the increasing significance of the impacts of a rapidly emerging organisational environment characterised by age discrimination, and this invariably impacts on organisational performance and productivity (Pitts et al. 2010). The authors investigated the impact of age diversity practices in organisations in the context of shared perceptions about age discrimination.

They also researched the impact of such circumstances on the affective and collective commitment levels of workers and found that such circumstances had an important bearing on the overall performance of the organisation. They concluded that age diversity is directly related to the constantly increasing patterns of age discrimination in organisations. They also found that age diversity in organisations creates negative impacts on organisational performance in terms of the negative effects of affective commitment. According to Ilmakunnas & Ilmakunnas (2011), it is extremely important for organisations to implement efficient management practices to deal with the rapidly increasing diversity in the workforce.

High levels of age diversity in organisations lead to different outcomes in comparison with the impacts of other issues, such as gender diversity. Such circumstances exist because age diversity in organisations is not given much importance through the implementation of affirmative action programs. This is because age diversity is a direct outcome of demographic changes taking place in developed economies and is not accompanied by concerted diversity-management initiatives implemented by organisations.

In addition, different theoretical explanations indicate a positive connection between higher age diversity and higher perceptions about the existence of an environment of age discrimination in most large organisations. In effect, such circumstances in the context of age diversity create a negative impact on people’s social integration. This often leads to weaker inclination of employee groups to work towards the achievement of common goals. According to Kunze, Boehm, & Bruch (2011), such rationales are effectively analysed through theoretical models, such as the similarity-attraction paradigm and the social identity and self-categorisation theory.

As per the similarity-attraction paradigm, people choose to associate with those people they consider to be similar to them in terms of demographic aspects, such as age. Such kinds of personal similarities are known to increase cooperative behaviours among workers and working teams. The same ideas related to age groups are delivered through the social and self-categorisation theories that declare that people will categorise themselves and others in keeping with demographic similarities pertaining to age, race, or gender (Strack, Baier & Fahlander 2008).

Simons & Peterson (2000) have argued that people generally get biased in favour of their own group members and tend to discriminate against the others in the organisational environment. More pertinent is the contention that a number of such groups can exist at the same time in a single organisation. It thus emerges that it becomes important for the management to effectively address the mechanisms that impact the relationship between diversity and performance.

According to Guillaume et al. (2013), most of the age diversity research conducted so far in terms of organisational performance has analysed the performance impacts of demographic diversity in terms of the workforce, work groups, and teams. Not much attention has been dedicated to studying the overall organisational outcomes that can be attained through efficient diversity management. The authors assert that such gaps can be easily filled by using the social exchange theory. It facilitates the study of employee welfare as a significant variable that links age diversity management to workers’ performance levels.

In this context, Guillaume et al. (2013) demonstrated that organisations can effectively indicate that they value and care for their age diverse employees by relying on compensation and appraisal policies. Through these practices, organisations do not place much emphasis on age and assess productivity on the basis of objective data instead. This leads to greater employee productivity and better organisational performance (Brown 2012).

Age Diversity and Employee Behaviour

Olsen & Martins (2012) posit that employees behave differently. Some workers are opposed to teamwork and prefer working individually. Others value collaboration and work towards the realisation of the goals of a group. Therefore, it is imperative to understand the viewpoints of individual employees before assigning them to particular groups. The Millennials value working in groups and endeavour to realise group’s goals. Conversely, Baby Boomers have difficulties assimilating into groups, as they appreciate the accomplishment of personal goals. Hence, managers should know how to handle such employees and assist them to relate to other workers.

Another pertinent factor is that employees react differently to uncertainty and changes. It would be difficult for an organisation to implement changes in a diverse workforce because of differences in the levels of tolerance. Some employees are hesitant about embracing change and require an assurance from the management that the transformation will not affect their careers. Olsen & Martins (2012) argue that organisational leaders should be patient when dealing with a diverse workforce. They should not implement changes rapidly, as the shift might not go well with some generations and could result in resistance.

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory defines masculinity versus femininity as the “distribution of emotional roles between the genders” (Mazanec et al. 2015, p. 302). The Baby Boomers emphasise typical male values, such as aspiration, materialism, power, and confidence. Conversely, generations X and Y accommodate female values, such as human relations. In view of such circumstances, the human resources managers must understand the masculinity versus femininity orientation of their workforce to ensure cordial relationships among workers.

According to Paludi (2012), some employees appreciate the significance of embracing realistic ways of resolving problems and the need to adapt to different situations based on prevailing circumstances. On the other hand, some workers use their experience to address prevailing conditions. Most organisations comprise employees with different orientations. Some are short-term oriented, while others are long-term oriented.

The human resources managers have an obligation to ensure that employee orientation does not interfere with the organisational development. Understanding the factors that contribute to Baby Boomers’ and Millennials’ satisfaction can help guarantee the success of diversity measures. While the Millennials value indulgence, the Boomers prefer restraint. Understanding the ways of satisfying the desires of different employees would help an organisation retain a motivated workforce, thus guaranteeing its growth in the long term.

Paludi (2012, p. 75) argued that “[m]anaging diversity is more than just acknowledging differences in people.” It entails appreciating the value of differences, promoting inclusiveness, and avoiding discrimination. Prejudice and discrimination result in low employee productivity. They affect employee morale and damage working relationships. Therefore, human resources managers should avoid stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination when hiring or terminating employees (Levy et al. 2012).

Wyatt-Nichol & Antwi-Boasiako (2012) aver that diversity management is a broad process that entails establishing an all-inclusive working environment. Personal biases are a major impediment to diversity management. Human resources managers require developing and implementing training programs to assist employees in changing their behaviours. Besides, they should establish efficient communication mechanisms to promote dialogue among workers from diverse age groups (Bezrukova, Jehn & Spell 2012).

Joseph & Selvaraj (2015) have argued that many organisations do not use the skills and talents of older workers effectively because of the existence of stereotypes and unrealistic perceptions about their higher wages and enhanced frequency of health issues. There are also perceptions and stereotypes about older employees not adopting organisational changes that occur due to technological advancements. Because of such behavioural patterns, their performance in comparison with that of younger employees is perceived as being very poor. In addition, many organisations believe that investments in training older employees do not provide good returns.

The authors have cited varied research reports that have concluded that working environments characterised by age diversity tend to be considerably less productive. It is for this reason for which managements of retail stores believe that higher age diversity among their employees will result in lesser profitability. Nevertheless, Joseph & Selvaraj (2015) have demonstrated through their research that there is no specific or noteworthy connection between the age of workers and the organisational performance.

In fact, the authors have asserted that several studies effectively substantiated how older employees proved to be as skilled and productive as younger employees are. The obvious conclusion that emerges because of such circumstances is that heterogeneous groups of workers contribute to achieving higher productivity in comparison with a workforce that is characterised by homogeneity in age.

Negative Age Discrimination

Negative age discrimination is associated with poor organisational performance (Wegge et al. 2008). Organisations in which employees develop perceptions about the existence of a negative age-associated environment that results from social breakup and age-diverse workers are prone to suffer from poor productivity. Kunze, Boehm & Bruch (2011) have used the social exchange theory in arguing that workers who have perceptions about age discrimination in organisations mostly develop poor emotional attachment to the organisation, which, in turn, adversely affects the organisational performance.

Backes-Gellner & Veen (2013) explored how age diversity in an organisation’s workforce impacts on its performance and productivity. Using theoretical models to assimilate outcomes from wide-ranging aspects of ageing and age diversity, they concluded that balancing costs and advantages of diversity allows for ascertaining the impacts of age diversity on organisational performance. In effect, greater age diversity leads to positive impacts on organisational performance only in situations in which the organisation engages in creative tasks and avoids the customary ways of doing things (Harrison & Klein 2007).

It is evident from these findings that Coca-Cola can adopt policies aimed at balancing costs and advantages of diversity. It will then be able to create positive impacts of age diversity on its performance. On the basis of the ongoing implementation of such policies, the company can make the required changes and frame the most effective policies to address age diversity.

From a different perspective, Arokiasamy (2015) has argued that age diversity can be associated with certain benefits given that the organisation adopts policies of collaboration and teamwork. Such efforts allow employees to become more productive in comparison with situations in which they work individually. Therefore, the advantages of age diversity are mostly attained only when the organisation is able to extract added productivity impacts emanating from team work among employees of different age groups. However, a necessary condition needed to attain such outcomes is that employees should have diverse skills and competencies.

This can occur despite the fact that employees of different age groups have dissimilar personalities and attitudes. At the same time, a high level of age diversity creates major challenges for HR personnel. For example, with the increasing age diversity, the number of older employees increases, and the management has to cope with higher pension contributions and higher costs of healthcare. Though, to substantially raise the commitment from employees, they only need to be motivated in a way, so they believe organisation’s vision and strategies and the benefits are aligned.

According to Peterson & Spiker (2005), negative age discrimination is primarily understood in terms of discriminatory practices of methodical stereotyping that are generally adopted against older employees. Nevertheless, in the current globalised environment, this pattern is better understood as the practice through which discrimination on the basis of age is carried out against old and young employees alike.

According to Baltes & Finkelstein (2011), negative age discrimination can be considered to be a variable related to the organisational environment. It is associated with the shared perceptions of employees in the context of fair and unfair age-associated practices, processes, actions, and behaviours of the management. In keeping with this understanding of the negative age diversity, Kunze, Boehm, & Bruch (2011) have argued that shared attitudes in the context of a negative age discrimination atmosphere in organisations occur primarily because of the prevalence of unfair organisational systems and procedures.

They also occur because of interpersonal events and activities among employees or between supervisors and employees. Companies characterised by age diversity tend to have greater negativity in terms of the environment of age discrimination. This kind of environment mostly occurs because of the prevailing attitudes about social categorisation and social identity. In such organisations, age is considered to be a major factor that leads to social categorisation.

It is well-known that globalisation has led to major changes in the job markets of the most developed nations (Ostermann 2010). The war for talent has become intensified because of the constantly increasing average age of employees. In addition, the reduction in the number of available young and skilled employees has led to the creation of extremely competitive and vibrant job markets (Beechler & Woodward 2009).

In referring to the resource dependence theory, Bieling, Stock, & Dorozalla (2015) examined the ways in which organisations confront emerging challenges related to age diversity. They found that organisations adopt practices of diversity management while framing compensation and appraisal policies and responding to the development of competitive job markets. That is evident that these practices have a major bearing on organisational performance in the current globalised environment (Rivas 2012).

According to Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory, “there is nothing like a universal management method or control theory, which is valid across the world” (Mazanec et al. 2015, p. 301). The theory helps explain the discrepancies among different cultures and age groups. As per the theory, the value systems of people are premised on six cultural dimensions, which are power distance, uncertainty avoidance, masculinity and femininity, pleasure versus moderation, long-term orientation, and individualism versus collectivism.

The dimensions differ across cultures and generations. Therefore, it would be hard for human resources managers to manage a diverse workforce unless they have adequate knowledge of the generational values of all the employees. Different cultures and generations have varied opinions regarding power distribution in the organisational environment (Samnani, Boekhorst & Harrison 2012). The older generation believes that it is hard to distribute power equally and is comfortable with hierarchical positions within an organisation. The Millennials believe in democracy and argue that all people are equal, and power must be distributed evenly. In view of such circumstances, it is the responsibility of the human resources managers to understand how different employees perceive power distance (Snape & Redman 2003).

Suggested Solutions to Age Diversity Issues

Solutions can be achieved by taking measures aimed at increasing the collective commitment of employees belonging to different age groups. From the perspective of these theoretical aspects, the managements of companies should adopt such practices as self-categorisation, social identity, and similarity-attraction to effectively address age diversity. According to Arokiasamy (2015), increasing age diversity is a common characteristic in many organisations and is well-explained through the social identity and self-categorisation theories.

People are known to categorise themselves into specific groups based on personal dimensions that are associated with self-categorisation and social identity. Consequently, people generally tend to favour their own group members and to discriminate against the members of other groups. It is pertinent to note that challenges may arise if an organisation distinguishes employees on the basis of their age or generational grouping. Such patterns may generate emotional discord among employees of different age groups and involve them in age-related discrimination (Kunze, Boehm & Bruch 2011).

In addition, age disparity has the potential for creating concerns about preference patterns of particular age groups in an organisation. It is apparent from some research studies that conflicts emanating from diminishing productivity are common in situations in which the organisational workforce structure is characterised by remarkable generational gaps (Passos & Caetano 2005). However, such opinions are not universal and are countered by a number of empirical research results.

In the context of the social exchange theory, Bieling, Stock, & Dorozalla (2015) attempted to ascertain how diversity management in terms of age improves organisational outcomes. They found that the implementation of age diversity management in the context of compensation and appraisal practices and policies led to enhanced employee welfare that had a strong bearing on organisational performance.

In keeping with the provisions of the social exchange theory, the authors have confirmed that compensation and appraisal policies associated with the notion of age diversity management have a direct and positive impact on organisational outcomes. This is because of the intervening impacts of enhanced employee welfare. If organisations decide to implement measures of age diversity management in their compensation and appraisal practices, employees in every age group benefit in terms of fair treatment and rewards in keeping with their work contributions and performance levels (Guillaume et al. 2014).

Consequently, employee welfare tends to increase, and the behaviours and attitudes of employees are supportive of organisational objectives, which leads to higher levels of organisational performance (Dobbin & Kelly 2007). In this regard, previous research has concluded that HR practices implemented in the context of age diversity lead to effective integration and management of age diversity issues, particularly in terms of compensation and appraisal policies (Wright & McMahan 2011).

It is evident that the adoption of age diversity management practices in the compensation and appraisal systems of organisations creates the intervening effect through higher levels of employee welfare and invariably leads to higher productivity in an organisation. It can be said therefore that measures of age diversity management in an organisation’s compensation and appraisal systems lead to greater employee welfare (Samnani, Boekhorst & Harrison 2012).

As highlighted by Cogin (2012), the perceptions that HR managers have about job markets are often due to the manner in which they view the prevailing levels of market dynamism. In this context, HR managers’ perceptions about dynamism in the job market depend on the manner in which they evaluate the frequency with which the market circumstances change. Consequently, the dynamism in job markets is the result of changes made by employers or employees in keeping with their respective circumstances. In fact, demographic changes enhance perceptions about dynamism, as HR managers have to address dynamic circumstances more frequently in the context of employees (Cui, Griffith & Cavusgil 2005).

In the context of such circumstances, organisations have to constantly involve in changing their HR policies so that they aligned with the need to remain competitive. As the workforce becomes highly age-diverse, there is greater divergence in the context of employee expectations, particularly among different generations, such as Millennials, GenXers, and Baby Boomers. In connection with these circumstances, organisations prefer to address rapidly changing diversity patterns and changing prospects by adjusting their HR practices and policies to the objective of enhancing the job market dynamism.

Gaps in Available Research and Frameworks

Age diversity is one of the lesser studied workplace diversity issues. More so, when it comes to pan-organisational studies. Available research on age heterogeneity is mostly in the area of top management levels (Somech, Desivilya & Lidogoster 2009; Williams, O’Reilly 1998; Jehn, Bezrukova 2004; Hamilton, Nickerson & Owan 2012; Pitcher & Smith 2001). These findings, thus, are not applicable to a wider workforce group.

Further, some researchers have also presented views that are contrary to the generally accepted views in favour of diversity. Building on Nkomo & Cox’s research (1996), they probed further to show that demographic characteristics are not constants, but socially constructed. Researchers delved in to enquiry that encompassed multiple questions, from the origins of the concept of diversity (Kelly & Dobbin 1998; Jones, Pringle & Sheperd 2000), to how it is implemented in organisations and specific professions (Litvin 2002, Zanoni & Janssens 2004), to more general organisational structures (Martinsson & Reimers 2008; de Los Reyes 2000; Wilson & Iles 1999; Dandeker & Mason 2001).

These researchers argue in favour of diversity being non-essential. They go on to counter the notion of diversity as positive and empowering which stresses on every persons’ unique capabilities and argue that diversity theories act as control mechanisms (Thomas & Ely 1996). Litvin (1997) proposes that this control is effected, e.g. through characterising the employees of the interest group based on their differences or essentialised group characteristics. This characterising, in a lot of cases is with with negative connotations (Zanoni & Janssens 2004).

Therefore, this study proposes to find a framework that is grounded in realities of a large corporation like the Coca-Cola, with focus on employees rather than just top management. As economies open up and workforce mobility gets easier, more organisations need to manage diversity. This study will try to provide recommendations to organisations in the specific areas of diversity management that are listed under research questions, with special focus on age diversity.

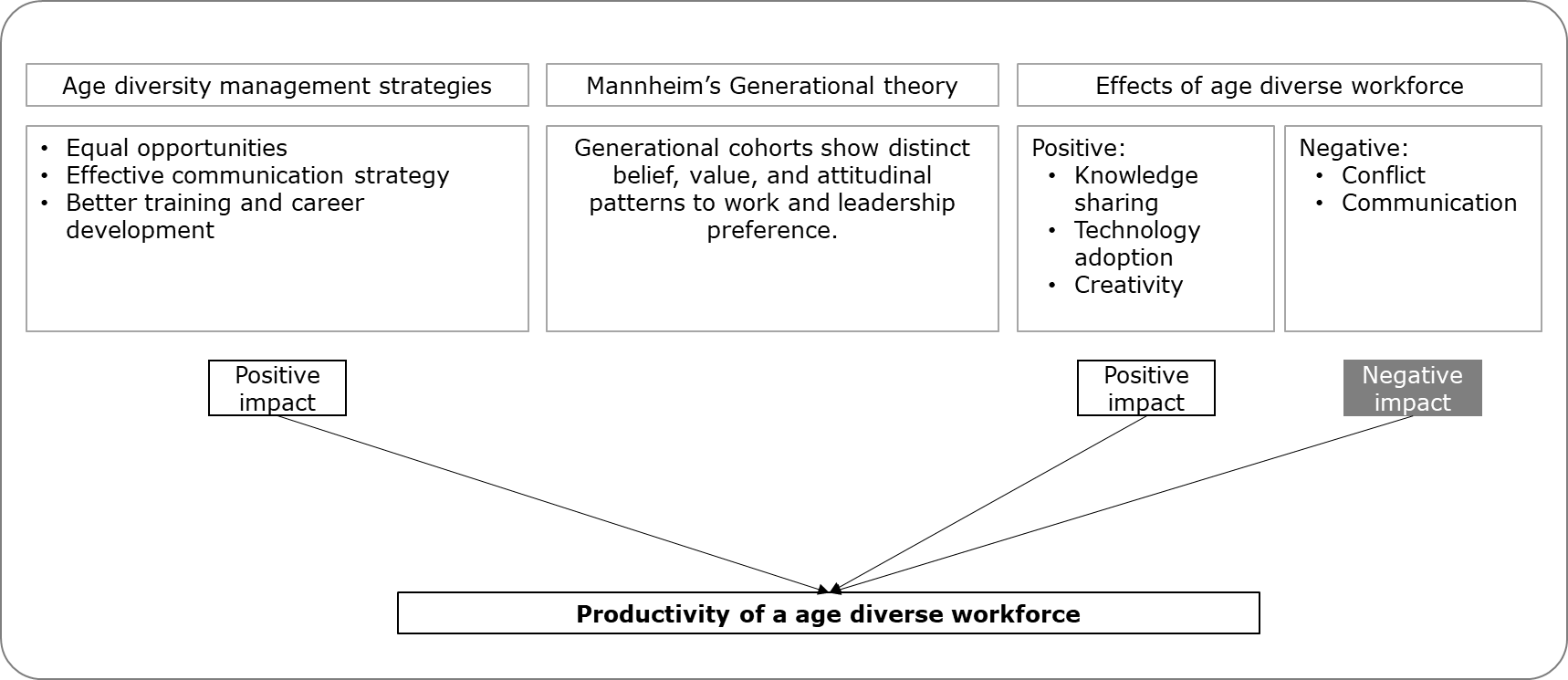

Conceptual Framework

A conceptual framework is critical to any research. It helps the researcher ensure that research has been framed in a coherent fashion in the research design (Green 2014). Apart from explaining the approach used to answer the research questions, it also helps group relevant theories into a larger framework. The visual representation makes it easier use and decipher, for the researcher and audiences.

Literature review has indicated gaps in available research and lack of in-depth work, in the area of age diversity. This research, thus, will use a custom framework, developed on the basis of, often considered seminal essay by Karl Mannheim, titled The Problem of Generations. In this essay, he proposed the generational theory. He proposed that individuals belonging to the same age group (generational units), will behave differently based on their geographic location (generational location), and exposure to socio-economic conditions (generational actuality). He further notes that shared experiences of generational units, location, and actuality shape the beliefs, values, and attitudes of individuals of a generational cohort (Mannheim 1952). He combined the positivist and the romantic-historical view to develop his theory.

Apart from the social framework, these generational cohorts are also present in workplaces (Lyons & Kuron 2014). Similar to the findings of Mannheim, other studies have found that generational cohorts in workplaces, too display similar beliefs, values, and attitudes towards work and leadership (Al-Asfour & Lettau 2014; Lyons & Kuron 2014). This makes it important for HR managers and business leaders to understand these cohorts and manage them in a way, that while utilising their strengths, minimises any chances of friction. It is imperative for managers develop effective strategies that can better manage the realities of an age diverse workforce (Hendricks & Cope 2013, pp. 717-725).

While a lot of research has been done in the field of other diversities, a lack of literature in the field of age diversity, indicates gaps in understanding of age diversity management. This makes this study important and of much interest to both, academic researchers and industry practitioner.

Research Design and Methodology

Research Philosophy – Selection and Use

Research philosophy is a standpoint regarding the way in which information pertaining to a certain phenomenon should be collected, evaluated, and utilised. Petty, Thomson, & Stew (2012, p. 271) argue, “The term epistemology (what is known to be true), as opposed to doxology (what is believed to be true), encompasses the various philosophies of research approach.” The two major philosophies of research approach are interpretivism and positivism.

Both the philosophies have roots dating back to the classical Greek era, with positivists like Aristotle and Plato. Renaissance and post-renaissance period saw emergence or eminent positivist and interpretive thinker like Durkheim, Bacon, Mill, Popper, and Russell who propagated positivism and Hegel, Kuhn, Marx, and Polanyi, among others (Hirschheim 1985).

The positivist approach holds that reality is “stable and can be observed and described from an objective viewpoint without interfering with the phenomena being studied” (Petty, Thomson & Stew 2012, p. 273). It poses that the researcher should be able to segregate the subject or occurrence that is being studied and make observations that can be repeated. However, the positivist approach is blamed for inconsistencies in results, as the method entails manipulation of reality to establish relationships among variables.

The interpretive approach holds that researchers can understand reality through subjective intervention and interpretation. The approach advocates the examination of research subjects in their natural environment and holds that it is imperative to study employees in their natural environment in order to understand how organisations address diversity management.

Positivism allows for predictions to be made based on historical observations, explained realities, and their inter-relationships. “Positivism has a long and rich historical tradition. It is so embedded in our society that knowledge claims not grounded in positivist thought are simply dismissed as ascientific and therefore invalid” (Hirschheim 1985, p.33).

It has been observed that in Organisation Science, interpretivism used to be the norm, at least till the late 1970s. Positivism has thereafter, established itself as the new standard (Dickson & DeSanctis, 1990), Orlikowski & Baroudi (1991). It was noted that in the case of leading US IS journals, about 96.8 per cent of research conforms to the positivist philosophy. Further, in a review of 122 articles in the GSS literature, Pervan (1994) also confirms that only 3.27 per cent could be categorised as interpretivist.

Given that this study is exploring issues pertaining to age diversity, a much debated but minimally explored area of study, this study will use the positivism approach. The approach will allow the collection of qualitative data through interviews, while allowing the researcher to look for commonalities in the findings and existing research. Further, the use of this philosophy, will provide established credence to a lesser probed topic.

Discussion and Rationale for the Selected Research Approach

The two primary research approaches are deductive and inductive techniques. The two methods differ in terms of their objectives. The inductive approach aims at coming up with novel theories to explain a certain phenomenon. On the other hand, the deductive approach strives to assess the veracity of specific theories. The method is suitable for studying specific and general aspects. It helps researchers narrow down general theories and come up with precise conjectures that are easy to evaluate.

This study aims at closing the gap that exists in prior studies related to diversity management. This will be done by probing the qualitative information collected and using the existing research. Hence, the deductive approach is suitable for this study, as it will enable the researcher to state and follow the research objectives. The plan will allow the researcher to concentrate on precise details, thus being able to address the research questions.

Research Design

The research requires using study design that will help answer all the research questions adequately. Lewis (2015) argues that researchers should select a type of research design based on the available resources and time. For this research, the pollster will use qualitative research design to gather data from the Coca-Cola Company. The qualitative approach helps researchers in examining the relationships among different variables.

Qualitative research can be descriptive or experimental, and this study uses a descriptive approach, as the respondents in this case are employees or managers at the Coca-Cola Company. The primary reason for selecting qualitative design is that it will allow the investigator to acquire in-depth information about how the company manages diversity. Moreover, the research design will help the researcher have a precise perception of what to anticipate from the study.

Method of Data Collection

There are numerous methods of collecting qualitative data, which include focus groups, observation, individual interviews, and action research among others. Apart from this, there are several secondary data collection techniques, that are used to strengthen the premises of the study. Marshall & Rossman (2016) build on the work of Brantlinger, who suggested seven categories of critical assumptions for qualitative research. Assumptions made for each of these categories, should shape the conception and implementation of the method in the study.

The main research instrument on which this study will rely will be interviewing, and it will be the sole method of data collection. This will be supported by critique of existing literature. The researcher will use open-ended questions to ensure that adequate qualitative information is gathered. Also, the researcher will conduct face-to-face interviews with the selected participants. It will enable the pollster to make clarifications in those areas with which he or she may not be familiar.

The investigator will avail the interview questions to the participants in advance to facilitate thorough preparation. The researcher has selected interviewing because it facilitates comprehensive examination of the research issues. The pollster can ask as many questions as possible to ensure that the research subject is understood. It is also possible to read and understand the nonverbal cues of the participants. The best option for collecting authentic primary data is to use the interview format through which open-ended questions are asked. The interview has been designed to effectively assess the values, attitudes, and perceptions of respondents (see Appendix I).

The questions aim at getting responses about how the participants feel about age diversity in their organisations and about the manner in which the issue was addressed by the management. The evaluation in this regard was done by compiling the responses of all subjects and analysing them to remove the duplication of ideas. This allowed the researcher to arrive at concrete conclusions about what the participants felt in the context of the varied age diversity issues that were put before them during the interview.

The questions asked during the interview had been prepared in advance and had been thoroughly examined and tested in ascertaining that they complied with the issues of data validity and reliability (Sarin, Challagalla & Kohli 2012). Secondary data for the research was collected by means of a thorough literature review on the topic. The information was obtained from credible and reliable sources, such as journals, books, articles, and reputed websites. During the interviews, all the respondents were asked the same questions. The questions were commonly addressed to employees and HR managers, although it was recognised that their answers would be different.

The two groups had different perceptions about their respective roles and the manner in which they would address issues of interest. Both employees and HR managers were required to express their opinions about the extent of stress that they had experienced in the working environment at Coca-Cola. They were required to comment on their opinions about the actions taken by the Coca-Cola management in addressing diversity issues in the working environment. They were also given the opportunity to state whether the management was taking proactive actions to resolve the age diversity issues among workers.

In order to know the extent of cooperation that existed among employees of different age groups, the respondents were asked to comment on the manner in which employees of different age groups interacted with one another and came forward to resolve their respective working issues. The objective was to know whether younger employees looked up to older employees in gaining from their experience and skills. At the same time, the questions were also designed with the intention to find out whether younger employees shared knowledge about their newly acquired technical skills with older employees.

The questions asked at the interviews also sought to determine if younger employees were open to being mentored by older employees. The answers to the questions would allow the researcher to know if older employees contributed to reducing frictions in the working environment. A major determinant of organisational success is the extent to which older employees promote team consistency and attainment of synergy.

The prevalence of such circumstances is best confirmed by the younger employees, which is why they were asked questions in this regard. The interviews also included questions about employee perceptions in the context of the utility they derived from Coca-Cola’s ongoing training programs. The interview also sought to extract information from employees about the age discrimination they might have experienced through any perceived discriminatory policies directed against employees of particular age groups. The employees were asked to comment on whether Coca-Cola’s processes of addressing the needs of employees of different age groups were fair.

This also allowed the researcher to learn about the anti-discriminatory measures taken by the organisation in terms of anti-age-discriminatory behaviours. Questions were also aimed at obtaining more information about Coca-Cola’s age-related practices and the transparency of the HR Department in terms of its actions.

The overall objective of interviewing the respondents was to determine the perceptions of respondents in the context of the extent to which age diversity existed in the workforce at the Coca-Cola Company and the extent to which employees and HR managers considered the ongoing organisational strategies in this regard to be effective and efficient. In order to meet this objective and to extract the maximum information from the respondents in the context of the prevailing practices that were related to age diversity issues in the working environment at Coca-Cola, the researcher asked them questions as given in Appendix I.

Gaining Access to Data

It was difficult for the researcher to gather information without gaining access to the Coca-Cola Company, which is why the need was recognised to design an appropriate strategy to obtain access to the required data. In meeting this objective, the researcher made use of reciprocity tactics to gain access to the required information in the context of interviewing employees and HR managers in the company. It was agreed upon with the Coca-Cola management that the researcher will share the findings of the research with the Company. In return, the company will allow the researcher to conduct the study, as the Company will benefit from the results of the study, too.

Study Population and Sample

The population for this study comprised the Coca-Cola Company’s employees and human resources managers. In particular, the sample population comprised 30 employees from diverse generations and five human resources managers who worked in the Birmingham area, Alabama. The researcher selected both employees and human resources managers and requested them to come prepared with the adequate information about their perception of diversity, particularly in the context of age diversity. Employees were informed they would have to provide information about how they felt about their colleagues from different generational groups. The managers were informed that they would be required to provide information about the strategies they used to manage diversity in the organisational working environment.

Given, the limitation of time and cost factors, a suitable sampling technique, that gives the researcher a healthy sample of the target group is important. There are multiple probability and non-probability techniques that are used by researchers (Robinson 2013). The key difference between the two is the methodology and the chances of each respondent from the population to be featured, in the study.

Table -1: Some of the established and accepted sampling methods.

Selection of right sampling method is critical in any research, to understand the correct picture of the population. It is more challenging in the case of qualitative research, as responses and their interpretation is more subjective. Further, to be able to select and interview, an adequate sample set, that represents the universe, is a challenge for any qualitative researcher (Oppong 2013).

The researcher decided to use purposive and convenience-based sampling techniques to select the participants. Purposive sampling is considered to be a good option for selecting respondents because it makes possible the identification of people who have prior knowledge and experience in the given field of activities (Palinkas et al. 2015). The sampling method tends to ensure that the participants are from diverse backgrounds. It also ensures that the researcher adopts viable strategies to select participants with different levels of technological experience, capabilities, sexualities, and age groups.

The sample size was determined on the basis of time availability and financial resources allotted to the research. After the respondents had been selected, they were apprised of the objective of the research and the purpose for which it would be used after completing the research process. The researcher took exhaustive confidentiality precautions by informing the respondents that their responses would be treated with utmost confidentiality and that their details would not be shared with any third party.

Research Context

It was decided to conduct the study at one of the Coca-Cola branch offices in the United States. It is known that the Coca-Cola Company is one of the major multinational corporations and has a diverse workforce. For decades, the Coca-Cola Company has managed to maintain its growth by recruiting a diverse workforce. Therefore, it was acknowledged that researching the company will enable the researcher to gain in-depth knowledge about the contribution of age diversity in the organisation’s productivity and performance. The research had to focus on age as the primary aspect of diversity.

Questionnaire

The study used a structured questionnaire (appendix I), that comprised of ten questions. The length of the questionnaire was set to ten, to ensure that the respondents can complete the survey easily and do not suffer from fatigue. It included nine close-ended and one open-ended question. The intent of questions was to ascertain the respondent’s understanding of the concept of age diversity (question 1), synergy between employees of different age group (questions 2-5), management’s actions (question 6) & commitment towards maintaining (question 7) & managing a diverse workforce (question 8), and affirmative actions by the management (question 10). The qualitative question (question 9) was to ascertain anti-discriminatory steps taken by the company to ensure age diversity in the organisation.

Limitations and Ethical Considerations

A major limitation of the research is that it relied on data collected at one time and that the respondents were chosen on a voluntary basis instead of being randomly asked to participate in the research. For this reason, conclusions could not be drawn in the context of causality (Antonakis et al. 2010). It is true that the research employed a comparatively big sample. However, its tendency to generalise in the context of the findings was reduced as the data was obtained only through a single cultural environment.

It is important to have respondents from different cultural backgrounds because different cultures tend to be characterised by different biases and discriminatory attitudes. A diverse sample population allows for appropriate reflection on individualism, long-term orientation, uncertainty, and uncertainty avoidance. These aspects have major potential for impacting on age discrimination in organisational working environments.

Another significant limitation was that almost all the information was obtained from respondents that were employed in a specific location in which Coca-Cola has its production facilities. Such circumstances raise issues of causal reciprocity, accuracy, and reliability. The literature has focused on the need to have reliable respondents, which implies that it was important to have respondents from different locations. However, this was not possible for this research, which was not of a large magnitude and had financial restraints on the extent of issues that could be researched (Kunze, Boehm & Bruch 2011).

In organisations characterised by diversity, ethics begins with assuming that all of the workers behave and work in accordance with the basic moral parameters. Only under this condition can they contribute effectively to the prevailing organisational environment. This was a major moral and ethical assumption while dealing with the respondents for this research. It is known that, regardless of an organisation’s size, behaviours that are not ethical can jeopardise the organisation’s functioning and its capabilities of attracting clients. Adherence to ethical conduct is also important if the organisation is to maintain cordial business relationships with entities with which it deals (Armstrong-Stassen & Lee 2009).

For a study like this one, the need for adopting different standards of ethics was acknowledged while exploring the employees of different age groups, primarily because different perspectives are associated with different ages. The financial and resources-related limitations of the research were determined before conducting the research. Consequently, it was extremely important for the researcher to maintain caution and keep up with the responsibility to provide reliable information in terms of respondents and their responses.

Data Analysis

The researcher had to analyse data using the thematic content analysis technique. It entails familiarising oneself with the gathered information, labelling or coding the data, identifying the apparent themes, evaluating the themes to ensure that they correspond to the data, and defining and renaming them. The study employed qualitative data evaluation techniques to gather primary and secondary information. The qualitative data generated through the open-ended questions asked in the interviews was analysed by using the content analysis technique. The technique was a process through which it was required to clean, code, and assess verbal responses of the subjects.

The data was compiled on the basis of responses of the subjects to the questions that had been recorded and subsequently transformed into written content. This was essential for extracting common patterns that existed among responses in the context of the respondents’ perceptions of age diversity practices in the Coca-Cola Company. The objective was to analyse common and recurring responses of the participants. In doing so, the researcher was able to determine the actual status of policy measures and consequent outcomes that had been attained in the context of age diversity measures taken by the Coca-Cola Company in the United States.

Results

The Coca-Cola Company has a very elaborate diversity policy. Apart from enforcing it on internal practices (Coca-Cola 2013), it also encourages its partners, that include vendors, to comply with them (Finan 2015). The company also, has consistently been recognised for its efforts in ensuring diversity by independent bodies like the Human Rights Campaign’s annual corporate equality index (Wells 2016).

It became apparent from the respondents’ replies to the questions asked during the interviews that they were fully aware of the complexities arising from an increasing pattern of age diversity among the workforce at the Coca-Cola Company. The general conclusion drawn from the compiled data is that age diversity is a major element of workplace diversity. The practice is very relevant in the current organisational environment.

It allows for designing appropriate strategies to attain success in a rapidly increasing competitive environment that has arisen due to the quick pace of globalisation. In effect, age diversity allows an organisation to benefit from a wide range of characteristics, experiences, and perspectives of the workforce. It became evident from the perceptions of the interviewed employees and HR Managers that age diversity among Coca-Cola employees motivated the management to make further attempts towards innovation and attaining excellence on different organisational fronts.

It was revealed in the literature review that issues in the context of age diversity in organisations emerged primarily because of some generalised perceptions that were created based on the generational patterns that characterised the social structure of organisations in the past. It is known that the current organisational environment is characterised by better healthcare delivery practices and that older employees now consider themselves to be more fit and capable of continuing with their jobs, even after attaining the age of 60 years. Consequently, greater age diversity has occurred at the workplace, as older employees now constitute a larger percentage of all employees.

In effect, the workforce structure is now characterised by remarkable generational gaps, which is apparent from the mix of Millennials, GenXers, and Baby Boomers that are part of the workforce at Coca-Cola in the United States. Such a structure obviously creates major issues of age diversity in the working environment. This is because each generation has its own priorities, perceptions, and ways of executing tasks in keeping with their respective value systems and worldviews. It is evident that the workforce is currently typified with high levels of age diversity. It is not unusual that older workers constantly complain about age-associated discrimination in the workplace.

They feel that they are not able to change themselves according to modern trends and effectively adopt the new ways of working that emanate from technological advancements. Consequently, they argue that it is not appropriate to label them as incapable of performing the required tasks. It is possible that, because of these reasons, older employees are perceived as lacking the inclination to imbibe new abilities and skills. In addition to such perceptions that have been highlighted in the literature, the younger respondents also reported during their interviews that their supervisors felt that older employees’ productivity was lesser than that of younger employees.

However, it also became evident from the responses of some middle-aged employees that Baby Boomers continued to be strong contenders for many jobs at Coca-Cola. They form a high percentage of the total workforce of the company. It is known in this context that Baby Boomers, GenXers, and Millennials form the main composition of the workforce in the United States.

From the interviews of some Baby Boomers that worked at Coca-Cola and were participants of this research, it was evident that they had not experienced age-related discrimination at the workplace. In addition, it is also confirmed by the literature review that older employees are considered to have the same or greater potential than younger employees. This is because of their vast experience, knowledge, and ability to make better judgments in complicated and challenging situations.

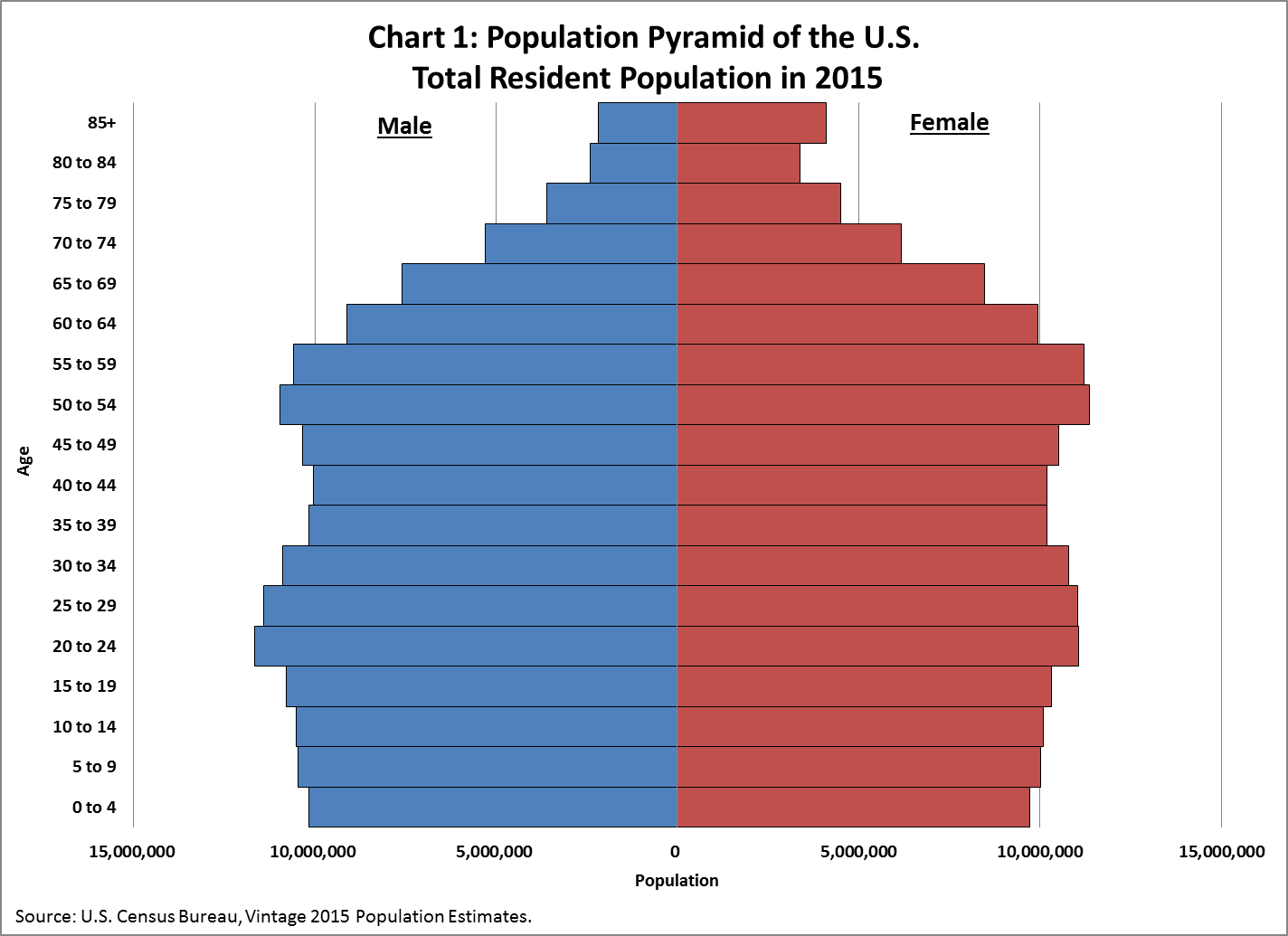

This is consistent with the demographic state of the United States as per the latest census data (Rogers 2015):

It also becomes evident from the literature review that wide-ranging perceptions exist about the inability of older workers to contribute to the successfulness of operation at the same level of productivity and creativity as that of younger employees. However, the results of the interviews revealed that the management at Coca-Cola did not believe in such patterns. In fact, it provided the same opportunities to employees of all age groups in keeping with their skills, experience, and productive outcomes. Nevertheless, perceptions exist among younger employees that the older employees are incapable of working and performing with the same energy as those younger employees have.

For example, one employee aged 23 years said that “young workers are always better as they can be easily moulded into specific job profiles quickly while older employees have to struggle in adopting new procedures and practices”. However, the same contention was negated by an employee aged 35 years who argued in favour of older employees and highlighted the instances in which he was assisted by them in resolving major issues at work. A manager responded in saying that, instead of considering multigenerational employees as liabilities that led to the creation of major challenges, it is better to consider the presence of older employees as an opportunity and asset.

The general opinion of the HR managers at Coca-Cola was that the Millennials were reframing the working environment by quickly adopting new communication technologies, new attitudes, and new production technologies. However, they also conveyed that companies should not “get into a mad rush” to only employ Millennials. They argued that older workers had their own distinct abilities in terms of their skills, experience, and knowledge about the working processes.

Such qualities are unique and cannot be found in younger employees. In addition, such qualities invariably add to the organisation’s abilities to address complexities occurring in the workplace. A common consensus that emerged from the responses of HR managers was that many organisations did not adopt positive practices of addressing age diversity. They asserted that, over time, such organisations tended to reduce the number of options available to them in extracting the benefits of age diversity. In the process, they harmed their long-term profitability and growth prospects in terms of productivity. It became known that the Coca-Cola Company in the United States recognised the extreme significance of age diversity in its workforce.

It has been adopting and implementing a policy through which employees of all age groups are given value through creating teams comprising workers from different age groups. Such teams are provided with the required facilities to work towards attaining synergy in productivity and other organisational functions, such as sales, customer service, and supply chain management.

It emerges that Coca-Cola has proved to be an innovative organisation that focuses on innovations aimed at developing a working environment that effectively addresses age diversity among the members of the workforce. The company has succeeded in embracing age diversity and has demonstrated that it attaches immense value to the contributions made by older employees. The company strives to remove age-associated biases that may exist among colleagues and managers.

When being asked whether older employees promote team consistency and attainment of synergy, one HR manager responded in asserting that some conflicts and disagreements were bound to occur because of the presence of a multigenerational workforce. However, it is not difficult to find solutions through teamwork and well-directed leadership interventions that can remove differences and add to the attainment of synergy among diverse groups of employees.

The manager informed that the Coca-Cola management favours the adoption of practices that aim at enhancing motivation levels of employees regardless of their age or cultural background. The focus of the management is placed on negotiating and finding positive solutions by exploiting the apparent similarities or differences, particularly among employees of different age groups.

The respondents were largely in agreement about the apparent clash of interests that exists among employees of different age groups. However, they were confident that such differences could be easily resolved through appropriate management interventions aimed at teamwork, sharing ideas, and making mutual efforts towards the attainment of team goals. One employee said that he himself believed that issues with older employees could be resolved through the practices that are in place at Coca-Cola in the context of teams that focus more on attaining common goals in terms of output and productivity.

Most of the employees did not report that they had experienced frequent stress in the context of age diversity issues in the working environment. They all praised the measures that had been taken by the management in the context of addressing age diversity issues. There was common agreement about the ability of younger employees to imbibe learning in terms of technological advancements faster in comparison with older employees.

However, the majority of younger employees conveyed that they had been always forthcoming in assisting older employees to understand and use new technologies. In addition, Coca-Cola has been taking initiatives in training its older employees to learn and imbibe the new technological processes. The purpose is to prevent their supervisors from developing prejudices against them or discriminating against them.

Most of the younger employees confirmed that a considerable part of their success in contributing to the organisational productivity rested on the mentoring that was performed by older employees. They were in agreement that older employs were constantly involved in guiding them and boosting their morale when they were confronted with challenges and difficult work situations. In effect, it has become known from the research that older employees play a major role in Coca-Cola.

They are active in creating a learning environment that is focused on maintaining high confidence levels among all the groups of employees. In performing such roles, older employees make positive contributions towards reducing conflicts and frictions in the working environment that may be caused by diverse statuses of employees from different age groups. By involving in such positive and constructive activities, older employees encourage consistent patterns of team cooperation and the attainment of synergy in organisational processes, which, in turn, leads to the achievement of organisational objectives.

The respondents reported that, for Coca-Cola, diversity meant being involved in becoming as inclusive as its consumers and brands are. This is reflected in the 2020 diversity vision of the company (Coca-Cola 2013), making it evident that the company has effectively disseminated the details of the policy and vision to the employees. The company gives equal importance to all of its employees regardless of age, gender, race, or place origin. Coca-Cola has been active in creating an inclusive environment in which every employee receives opportunities to contribute to the common success in terms of teamwork and performance.

It also implies that seeking wide-ranging opinions and feedback on varied aspects of employee policies should be involved. The company does not practice or tolerate any kind of discrimination in the context of age diversity that characterises its working environment. In effect, the company benefits through varied perspectives in terms of the capabilities and ideas that are made available by an age-diverse workforce and uses them to create maximum value and welfare for its employees. The biggest benefit for Coca-Cola in adopting positive policies in terms of addressing age diversity pertains to the competitive advantage it gains in all of its markets in the United States.

The knowledge gained through such policies allows the company to meet the needs of its varied markets comprising consumers that are characterised by different demographical features. It became evident from the responses of some HR managers that Coca-Cola adopted impartial appraisal systems that did not create any types of systematic biases against employees of specific age groups. The company ensures that employees of all age groups are provided with feedback on a regular basis, which increases the benefits of fair treatment and age diversity in the working environment.

It became apparent from the responses of the participants that Coca-Cola remained committed to taking anti-discriminatory measures that focused on checking the anti-age-discriminatory behavioural patterns of some managers and employees. For its part, the Coca-Cola management has been promoting initiatives aimed at providing the required training that would allow employees of all age groups to refrain from having perceptions about being different or less competent in comparison with the employees of other groups.

The company ensures that employees of all age groups are provided with essential inputs. They are apprised of the threats associated with the implementation of discriminatory policies that may be potentially harmful to the employees of particular age groups. In its training programs, the company strives for clarity in declaring that its policies are in no way aimed at discriminating against employees of different cultures or age groups.

Through its ongoing training programs, it conveys the message that performance appraisal is performed primarily on the basis of merits related to employees’ contribution to the organisational productivity and the attainment of organisational goals. Training programs include guidance in diversity affairs that focus on the crucial need for adopting fair processes while dealing with employees. The management invariably assures employees during its varied training programs and employee gatherings that it is committed to the adoption of fair processes and does not pursue discrimination against any group of employees. The adoption of these processes is a clear indication that the age-associated practices of the Coca-Cola’s HR Department is transparent and focused on removing discrimination based on age.

Analysis and Discussion

Bieling, Stock, & Dorozalla (2015) have argued that practices of age diversity management have a strong impact on organisational performance. They cited the relevance of the resource dependence theory in understanding the relationships between organisations and the prevailing demographic environments. According to Ortlieb & Sieben (2012), the resource dependence theory allows for predicting the extent to which organisations will experience long-term shortages in the context of the availability of crucial resources for executing planned strategies. The theory characterises organisations as open systems that are influenced by external factors through the influence of resources that prove to be crucial for their functioning (Drees & Heugens 2013).

Therefore, organisations are heavily reliant on such crucial resources that impact on their decisions and execution strategies. In this context, it is possible to say that, with the increasing organisational dependence on external resources, the Coca-Cola Company in the United States faces greater uncertainty and has to consequently work towards reducing uncertainty and dependence. In view of the emerging demographic developments, organisations are experiencing a shortage of skilled and qualified workers.

Such situations invariably enhance uncertainty among HR managers in organisations. Solutions to these issues are best achieved by adopting policies of attracting and retaining workers of all age groups by implementing compensation and appraisal practices that can be linked to different concepts of age-diversity management. In this regard, the objective of Coca-Cola is to treat employees of all age groups in equal, fair, and impartial ways.

There is the opinion that the most developed nations, including the United States, are characterised by a rapidly ageing population, while the percentage of younger workers in these countries is gradually declining. It is for this reason that the issue provides vast opportunities for researching the causes and possible solutions for these problems, which are gradually becoming more pertinent with the increasing globalisation. Bieling, Stock, & Dorozalla (2015) have highlighted the issue of age diversity management in organisations. They assert that solutions can be found through designing and implementing appropriate compensation and appraisal systems.

The consistent increase in the average age of employees and the reduction in the number of young and skilled employees have the potential for drastically transforming the job market environment in developed economies. In this regard, Kulik et al. (2014) have highlighted that organisations in a globalised environment face challenges of not only meeting the need of employing and retaining skilled workers but also coping with the shortfall of competent employees. Consequently, such companies as Coca-Cola have to attract skilled younger employees and take effective measures aimed at retaining skilled and qualified older employees.

Under such circumstances, companies are invariably dependent on the experience and contributions of older employees (Goebel & Zwick 2010). These circumstances imply that such organisations as Coca-Cola need to keep improving their HR practices and policies in keeping with the rapidly changing developments caused by globalisation. In effectively responding to the emerging changes, they need to adopt creative strategies of attracting, motivating, and retaining older employees.

Possible strategies include the introduction of age diversity practices in the compensation and appraisal policies of an organisation. According to Hedge, Borman, & Lammlein (2006), the best compensation systems that effectively meet the needs of age diversity management make use of practices that focus on providing equal pay for equal performance and work. Such practices should not attach value to the age of employees or be characterised by biases based on age.

Kunze, Boehm, & Bruch (2013) have made major contributions to the literature dedicated to age diversity. They investigated the impacts of age diversity on organisational performance by relating their research to the theories of social identity and social categorisation. They argued that organisations characterised by high age diversity were bound to experience the occurrence of sub-grouping processes.

They asserted that such practices led to the creation of perceptions among employees of the existence of a negative age discrimination environment in organisations. It can be concluded that this negative environment of age discrimination is directly associated with organisational performance. Under such circumstances, the negative age-associated stereotypes and diversity-focused HR initiatives (as introduced by the management) act as intermediaries. They promote enhancing and soothing the processes of social categorisation that affect organisational performance in companies characterised by high levels of age diversity.