Introduction

Language teaching is inevitably associated with the implicit teaching of culture because the language does not exist separate from other external factors; it is integrated into the culture of societies and shows the values and beliefs of different communities. This means that language reflects the culture and has an influence on it. Regardless of the culture, learning a foreign language means learning about the ways of life in another culture (Paige et al., 2017, p. 1).

As discussed in chapter three; culture is defined as a set of knowledge and characteristics of a particular group of people who share the same language, religion, conventions, social habits, and behaviors (Choudhury, 2014, p. 2; Spencer-Oatey, 2017, p.5). As a consequence, scholars pay careful attention to how the culture is presented in language textbooks as well as how undesirable cultural aspects have to be filtered for teaching languages in Libya (Al-Obaidi, 2015, p.6). The purpose of this chapter is to analyze the cultural contents of three levels of English for Libya textbooks to determine how culture is presented in these language textbooks. The analysis is based on the criteria outlined by Byram (1989) and by Dweikat and Shbeitah (2012) in their works.

Criteria for the Analysis of Cultural Contents in English for Libya Textbooks

Criteria for the analysis of cultural aspects in the textbooks are adapted from Byram’s list of cultural aspects that should be presented in educational materials as they contribute to learning languages with a focus on the cultural dimension (Byram, 1989, p.67). This list includes eight factors: social identity, social interaction, belief and behavior, social and political institutions, socialization, history, geography, as well as national identity, and stereotypes.

It is noteworthy that some dimensions seem very similar or even overlapping, but the core concepts of these categories differ significantly. These similar aspects are social identity and social interaction. According to Byram (1989), social identity can be defined as “a part of an individual’s self-concept” that is based on this person’s “membership in a social group (or groups)” (p. 52). Whereas, social interaction is a multidimensional exchange between people that can modify people’s identities and tends to “serve as a basis for restructuring under the influence of new experience” (Byram, 1989, p. 109). In simple terms, the social identity is a set of an individual’s self-concepts while social interaction is the process that affects people’s identities.

The criteria mentioned above were combined with Dweikat and Shbeitah’s cultural components with a focus on relations, customs, and traditions to Byram’s list of cultural aspects. Dweikat and Shbeitah’s components include economic, social, literary, historical, geographical, religious, man-woman relation, political, customs and traditions, and a way of living (Dweikat and Shbeitah, 2012, p.11). The two classifications are quite similar with only slight differences in concepts or focuses. For example, Byram (1989) pays significant attention to stereotypes while this area is not considered by Dweikat and Shbeitah (2012). At the same time, stereotypes often shape the way people see each other, so this category was included in this study. The complete list of eight cultural aspects selected for this study is presented in table 1 below.

Table 1. Checklist for Content Analysis.

This study aims to answer the following research questions:

- Are both English Speaking and non-English speaking Cultures’ values represented in English for Libya coursebooks?

- To what extent are foreign cultures included in English for Libya coursebooks?

- To what extent are Arab-Islamic cultural values included in English for Libya coursebooks?

- Are there any elements of intercultural competence?

Overview of Course Books’ Organization

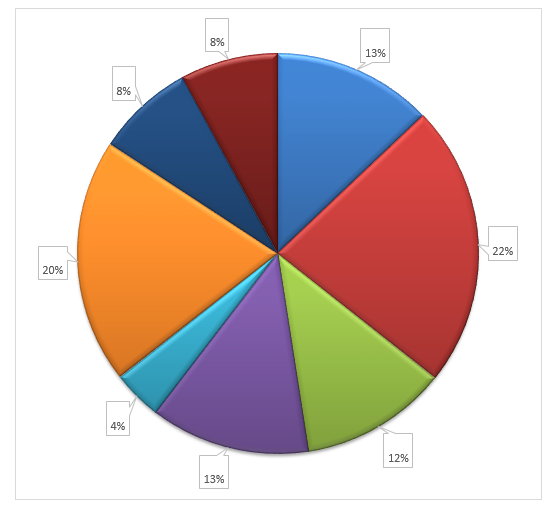

The syllabus of the English for Libya series for secondary students is the Secondary Level 1 textbook consisting of eight units, as shown in Fig. 1:

Each unit of the coursebook is categorized based upon reading, vocabulary, and grammar, speaking, writing, listening, pronunciation, and review units are included. Images play a dominant role and the activities are mostly informed by the task-based approach.

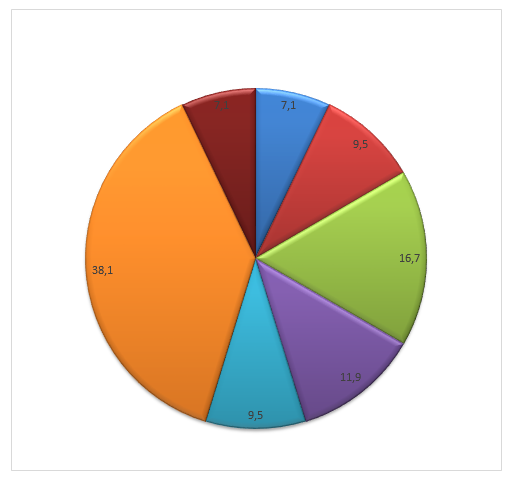

The Secondary Level 2 coursebook is divided into eight units, but the focus is on different skills and competencies, as illustrated in fig.2 below:

Each unit of the coursebook is based upon reading (two lessons per unit), vocabulary (three lessons) and grammar (three lessons), speaking (one lesson), writing (one lesson), and listening (one lesson).

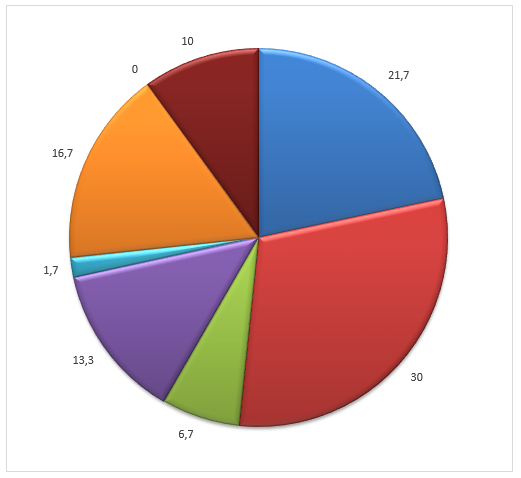

The general organization for Secondary Level 3 follows the level 2 like the scheme; as shown in Fig3:

The Level 3 coursebook introduces the more detailed grammatical practice and challenges students to understand the meaning and the gist of reading and listening exercises.

Data Analysis

Analysis Results

- % = (Number of examples per category / total number of examples per culture) * 100%

Each coursebook was analyzed separately (Appendix A). The examples of cultural aspects were coded (Appendix A), and then, the following formula was applied to quantify the percentage of their occurrence:

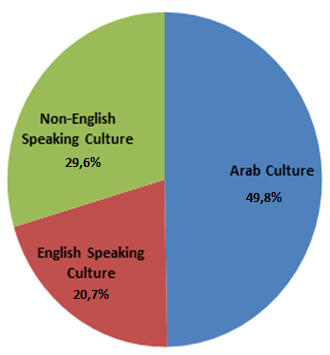

The total number of examples found in the three textbooks for three cultures was 203. Of these, 101 examples of cultural aspects were related to the Arab culture, 42 were related to English-speaking cultures, and 60 were related to non-English speaking cultures. The percentage of examples associated with different cultures about the overall number of examples is presented in fig. 4

- History, Historical Events, Social and Political Institutions: 13 examples / 101 (total number of examples for the Arab culture) * 100% = 12.9% (see table 2).

The following formula illustrates how percentages were calculated concerning the first category, i.e. history:

Table 2 below sums up the results. The number of examples for each cultural aspect shown in table 2 is retrieved from the three tables presented in Appendix A (where a page number refers to each example). The same formula was applied to all the dimensions presented in table 1. The frequency of examples associated with different cultures is also presented in the form of diagrams (see fig. 5, fig. 6, and fig. 7). The comparison of this frequency among the three cultures is illustrated in figure 8.

Table 2. Percentages of Cultural Aspects.

The analysis of the cultural dimensions in question shows that the authors put a different value on each category. For instance, when it comes to the Arab cultural context the major focus is on categories two (geography) and six (behaviors, routines, ways of living, habits, and traditions). These aspects make up over 40% of the cultural content. The rest of the dimensions are represented almost equally (approximately 10% each), suggesting that the categories have equal value for the authors.

Category number 5 life cycle and socialization is the least represented concept, and interestingly enough, category 5 is mentioned occasionally also about non-English speaking contexts (see fig. 7). The distribution of the space devoted to the categories under analysis is quite different in the English-speaking context.

The most pronounced dimension among the examples related to the English-speaking culture is the sixth category. Behavior, routines, ways of living, habits, and traditions are described in quite a significant detail, amounting to almost 40% of the examples (see fig. 6). The authors tend to put a considerable value on these aspects. This attention is consistent with the views that traditions and routines can help learners develop an understanding of the culture and language they try to master (Tsai, 2017). Another category that receives substantial attention is the one associated with social identity, social class, and social stereotypes (17%) (see fig. 6). The remaining aspects receive almost equal attention, which shows that the authors seem to regard them as important but not critical issues to pay attention to.

As for the non-English speaking contexts, geography is the most frequently described aspect (30%), followed by category 1 (21,7%) and category 6 (16,7%) as shown below (see fig. 7).

It is possible to assume that the authors want to acquaint learners with the locations of these countries and some of the most meaningful cultural peculiarities of the people living there. The authors contribute to the development of learners’ general knowledge about this world to make them more prepared for cross-cultural interactions.

The comparison of cultural differences across cultures shows that history [category 1], geography [category 2], and behaviors [category 6] are the three categories that receive the most attention (see fig. 8). These dimensions help learners to develop their general knowledge about the world and the place of their culture in the global context. Category 5 (socialization and life cycle) is the least described. This can be rooted in the authors’ major focus on the social context rather than the individual aspect. Such domains as the development of relationships and international trends are out to the fore, which can be partially due to the peculiarities of English learning. Students are trained to communicate, which makes social components central to the learning process.

The Analysis of the Identified Categories

In this section, each category will be analyzed in detail. The contexts of Arab, English-speaking and non-English speaking countries will be explored in terms of the eight categories. The section The Analysis of the Identified Categories includes a detailed description of the findings with a discussion of the central trends and peculiarities. The main discussion of the results will be provided in the Discussion section.

Before considering the contents of the books, it is necessary to emphasize that some categories overlap due to their focus on the social aspect of people’s lives. The most evident overlap is associated with categories 3, 4, 5, and 6. These categories may be combined into one, but this would make the analysis less complete due to a lack of attention to multiple components of the society. Moreover, the examples of the tasks given in the books are sometimes used more than once as they address several aspects of people’s life.

First Category: National History, Historical Events, Social and Political Institutions

This category refers to the development of society and the understanding of the achievements made through generations. Social and political institutions, as well as economic factors, are also discussed within this category. This aspect of culture often shapes the way societies, traditions, and languages evolve. Of all the examples found, 12.9% were related to the Arab cultural context, 7.2% were concerned with the English-speaking culture, and 21.7% were related to the non-English speaking (international) context. An example of history about the Arab culture can be found in the following reading task, which included also visuals that reveal the conventional image of the Arab world (fig. 9).

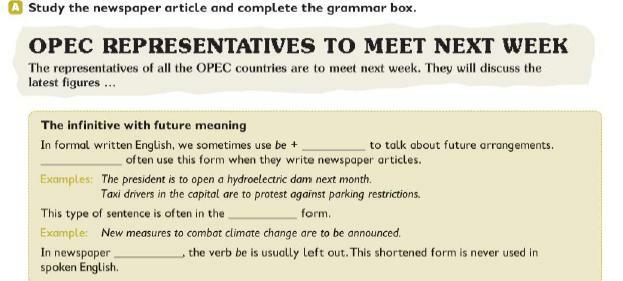

In Secondary 3, examples were found about the economic development of an Arab country (see fig. 11) and international economic relations (see fig. 10). The grammar exercise based on a text about OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) provides students with information about an international organization, thus contributing to the cultural education of English language learners using expanding their knowledge regarding international relations (see fig. 10). This element refers to the social and political aspects covered in the first category (see table 1). Economic relations are part of the social and political cultures of countries that influence these countries’ national agenda.

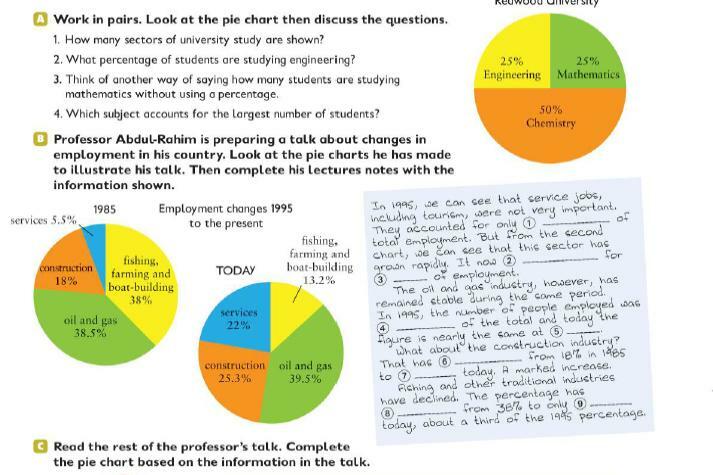

The reading comprehension exercise in Secondary 3 includes a lecture by Professor Abdul-Rahim, which teaches students about the economy in an Arab country that is not specified (see fig. 11). Learners can see different spheres and occupations, in which workers are engaged. This exercise gives them knowledge about how the industries are divided as well as how they have changed with time. This exercise can be regarded as an example of the authors’ focus on the use of English as a global means of communication in different spheres. In this case, students could see the importance of English in the sphere of global business.

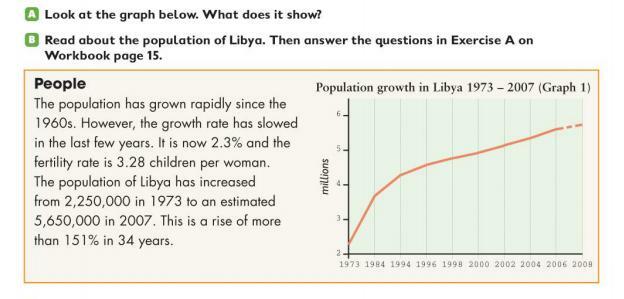

A crucial role in the learning process is played by the authors’ awareness of how to integrate economic notions as a part of the cultural context (see fig. 10 and fig. 11), so that students can understand the economy as an integral part of a country’s functioning. Political aspects can be introduced into English language learning in terms of historical and modern facts about the countries’ populations, voting statistics, past presidents, and other aspects. For example, lesson 8 in Secondary 1 gives many facts about the number of people in Libya and the increase in population over time (see fig. 12).

Some English textbooks for language learners can contribute to the marginalization of the Arab minority in the world (Awayed-Bishara, 2015, p.517). However, the attention to the Libyan context in these textbooks proves the opposite because much attention is paid to the Arab culture.

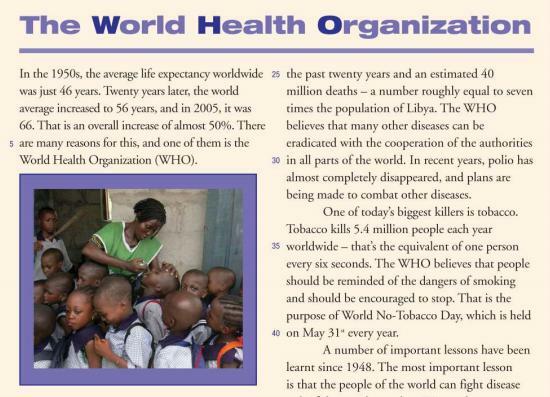

Examples of international institutions are also presented in these course books. Thus, the example in Secondary 3 introduces the World Health Organization and indicates its efforts to manage social health-related issues at a global level (see fig. 13).

As for the non-English speaking context, the books under consideration touch upon some historical facts concerning countries across the globe. For example, in Secondary 3, some historical facts are introduced associated with Egyptian pyramids. In Secondary 2, some facts about Venice are highlighted. In both cases, students are encouraged to discuss the past of these places and relate it to the modern world. However, it is necessary to stress that the primary focus of the books’ contents is concerned with international institutions rather than particular places and countries.

Second Category: Geography

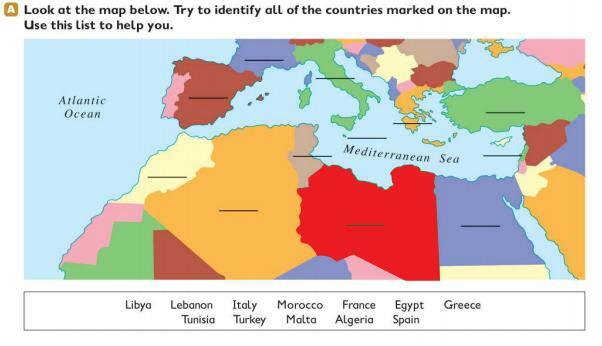

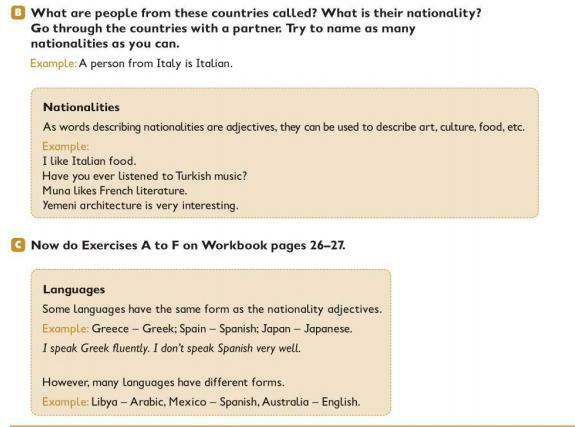

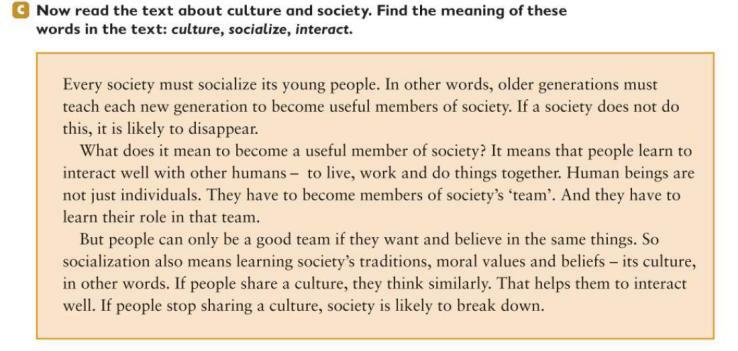

The second category, related to geographical aspects, is not only an important component of teaching culture and languages but is also essential for learners’ intercultural competence. References to the geographical aspect are frequently found for all three levels in the books chosen for the analysis. It is noteworthy that these concepts are presented in the textual and visual forms that facilitate the perception of the written text. The use of maps in the exercises is useful for encouraging the comprehension of new vocabularies (names of countries, and other toponyms) and their usage.

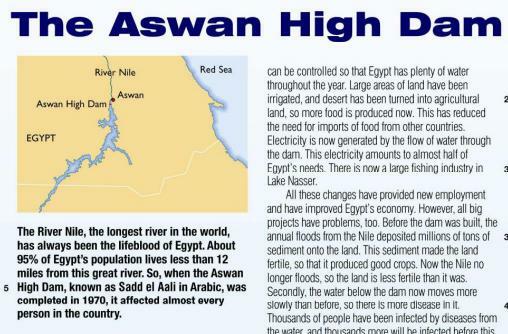

The exercise to match countries with their drawings on the map allows students to use their prior knowledge of geography and discover something new about the world. Many exercises that seem to focus on geographic aspects are culturally oriented. For instance, the task concerning the Aswan High Dam (see fig. 17) does not simply reveal some statistical data on the Nile or Egypt. The provided text sheds light on people’s way of living as well as their attitudes towards certain changes in their lives. The authors place a great value on culture, which is one of the pillars and building blocks of cross-cultural communication.

The necessity to use culturally appropriate names when describing people of different ethnicities is an important factor in language learning. This choice allows learners to understand the existing difference between nationalities, languages, names, and designations of people (Ford, 2017). The category National Geography is rather frequent as the tasks associated with this aspect account for 22% of culturally-related assignments. The international or non-English speaking dimension turns out to be the most frequent accounting for 30% of the related examples, whereas, 22.8% is devoted to the Arab cultural context, and 9.5% concerns the English speaking context. Geography-related tasks include maps. The same approach is used for some non-English speaking countries (see fig. 14).

It is possible to assume that national boundaries are regarded as important aspects to pay attention to with students asked to use their background knowledge to discuss countries’ locations marking them on maps (fig. 14 and fig. 15). The tasks related to the discussion of state borders account for 26,7% of geography-related exercises. These cases also represent the authors’ focus on paying students’ attention to international contexts the interaction between the Arab world and other countries.

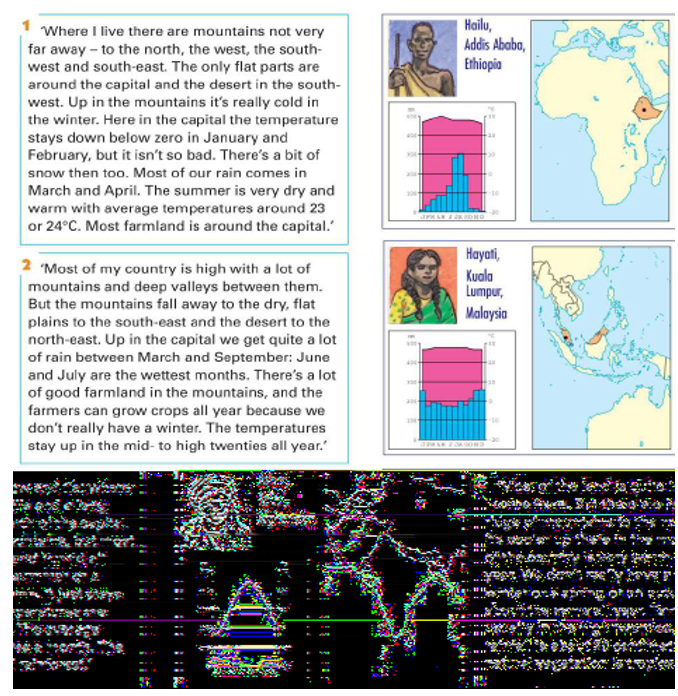

In the tasks below, students learn about different countries while seeing them on the maps, some statistics, and images of the residents of these countries (see fig. 16). Geographic descriptions and references to geographic peculiarities of counties are dispersed among assignments associated with the category National Geography. Although these components account for 42.2%, this content comes together with referrals to the inhabitants’ cultural peculiarities (see fig. 16) or environmental issues (see fig. 17).

Many tasks are associated with the discussion of environmental issues as their persistence and the solutions depend on the geographic location of the site. Some assignments involve the acquisition of knowledge as some facts concerning geographic sites are provided (fig. 16). In some cases, there are maps representing state boundaries that help students learn about the Arab world and other countries.

Many examples (31.1%) presented in the course books are related to climate, weather, and ecological factors. The analysis of ecological aspects in addition to climate is crucial for advancing multicultural competence (Napier, 2014, p.1610). These examples can be found in Secondary 1 (see fig. 17). The climate and ecological factors are associated with the intercultural dimension because problems like oil spills are relevant for any country (Jernelov, 2010, p. 353; Marsiglia and Booth, 2014, p.423; Taguri et al., 2008, p. 113).

Such choice of the topic shows that the authors aimed to raise the awareness of climate and environmental issues and the impact of human activities (see fig. 18). The text concerning the dam (see fig. 17) reveals some environmental issues associated with “all big projects” (Adrian-Vallace & Schoenmann, 2008, p. 79). The authors concentrate on some global issues rather than region-specific problems.

Importantly, geographic aspects are mainly related to locations and environmental issues. The focus is on Arab and non-English speaking contexts. Many tasks are linked to the problems related to oil production, which is typical of Arab countries. However, these environmental concerns are highlighted in terms of their global impact.

Third Category: Social Identity, Social Class, and Stereotypes

Category 3 covers the cases related to social classes, stereotypes, and social identity. This category is one of the central dimensions to be analyzed when considering cultures and their representation in texts. People are divided into numerous groups as they perform multiple social roles in society, which makes it important to understand their roles in relevant social units. These groups include families, teams, classrooms, and other organizations where different people are united with the same purpose. In the books under analysis, there are not many examples of such concepts as the division of people into social groups other than the family.

In the Arab cultural context, identity, class, and stereotypes represent 11.9%, while examples referred to as the English speaking context represent 16.7% of all relevant occurrences, and examples related to non-English speaking cultures represented 6.7%. Such figures may be a result of the persistence of stereotypes concerning the English-speaking world. These stereotypes are promulgated via various media with the Internet playing the major role (Dweikat and Shbeitah, 2012, p. 11).

It is also possible to assume that stereotypes related to the Arab context are less pronounced as Libyan students, as well as other Arab learners, do not have stereotypical views on their own culture. However, they are encouraged to acknowledge that such stereotypes exist. The awareness of some common stereotypes can help English learners discuss various topics related to cultures of different (as well as their own) countries.

However, some examples presented in other categories (such as categories 4, 5, and 6) partly relate to this cultural dimension. For instance, a family is introduced as a specific social group where each member performs his or her roles and has certain responsibilities (see fig. 28). Family-related concepts are indeed elements of the social identity developed throughout centuries are quite culture-specific.

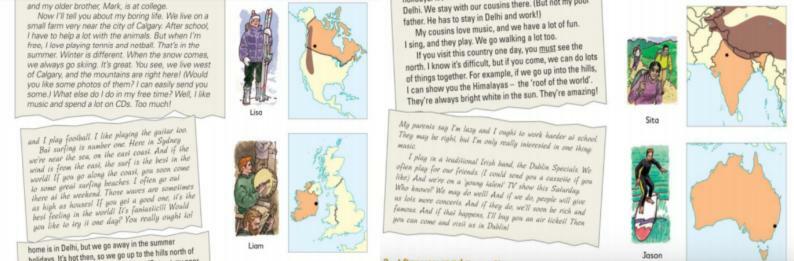

In Unit 4 of Secondary 1, the reading exercise includes letters sent by people from around the globe with images showing how they look and what location on the planet they are from (see fig. 19). These examples are associated with some cultural stereotypes, for instance, a young man from Australia is represented as a surfboarder. The woman from Canada is depicted holding skis although Canadians do not wear warm clothes all year long.

Other tasks in the same unit have features related to countries, nationalities, and languages that accentuate social and national identity (see fig. 20).

It is noteworthy that category 3 (Social Identity, Social Class, and Stereotypes) partly overlaps with category 2 (National Geography), but the focus here is on cultural contexts rather than geographical elements. The exercise in figure 20, for example, has been classified as belonging to category 3 as it is characterized by the presence of stereotypes. When speaking of literature, the authors mention French contexts, for food, Italian culture is chosen (see fig, 20).

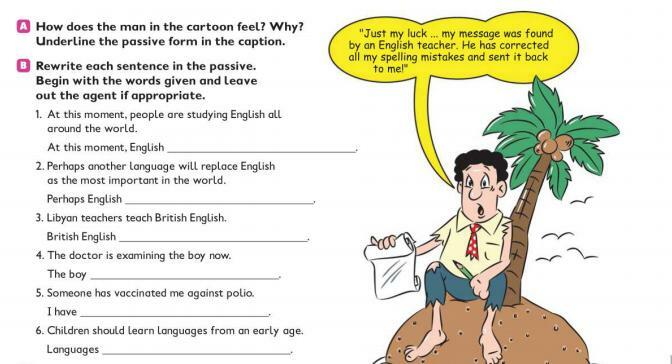

In Unit 8 “English in the World” of Secondary 3, several examples were found as they are related to culture and languages with a focus on identity (see fig. 21 and fig. 22). Here, the global use of English is emphasized. In the example shown in the picture (see fig. 21), the man uses English to make sure that he will be understood and saved, implying that English is more likely to be understood as compared to other languages. This example helps learners to develop a sense of urgency and relevance of their studies, with English shown as a tool to deliver vital messages. The instance also reveals a stereotypical view of an English teacher as inflexible professionals who are keen on finding errors and imperfections, thus making learners feel uncomfortable.

The task in figure 21 shows that the English language is used around the world, and it can serve as a platform for acquiring new social identities. A sentence that was given in the task (fig. 21) is rather illustrative. It goes as follows, “At this moment, people are studying English all around the world” (Adrian-Vallace et al., 2008, p. 94). The authors imply that a person can belong to a group of English learners as being out of this constantly and rapidly growing community is not desirable. The next sentence in the exercise suggests that the authors deem English to be “the most important in the world” (Adrian-Vallace et al., 2008, p. 94).

At the same time, the international dimension of Arabic is stressed as it is a part of millions of people’s social identity (see fig. 22).

This example indicates regions where Arabic is used as a means of communication, suggesting that the language, just like English, has an international status. The map includes the countries where Arabic is spoken while English is not represented at all. Apart from the visual representation, the idea of the role the Arabic language plays in the international arena is also put forward through the task content.

With the help of these examples and the connection between international communication, national identity, and stereotypes, an idea of how to teach students about the role of language can be developed, and students’ awareness of its role in the construction of social identity can be raised. The authors try to make students understand the value of speaking English for the sake of their future careers as well as their present social dimensions.

This language is presented as an international tool for communication that can become a platform for the interaction of people across the globe. At the same time, the authors also pay tribute to Arabic that also has a status of an international language. The learners are encouraged to appreciate their mother tongue and be proud of it while being motivated to learn English that is linked to more opportunities in the global arena. The opportunity to be a part of different social contexts is brought to the fore throughout the books under analysis.

Fourth Category: Social Interactions and Relationships

Category 4 covers the content associated with relationships and social interactions. As has been mentioned above, this element is closely connected with other categories, but it should be discussed separately. It is insufficient to identify some stereotypes and existing social classes and groups. To understand the way cultures are represented in texts, it is essential to trace the ways people interact within the contexts of their cultures as well as in cross-cultural environments (Dweikat and Shbeitah, 2012, p. 16).

Social interaction and relationships are represented in all three-course books with a strikingly even distribution. 12.9% of examples are related to the Arab cultural context, 11.9% are related to the English-speaking cultural context, and 13.3% are related to the non-English speaking cultural context. Such element as interpersonal relations, especially between males and females, is an element of a clash between western and Arab countries.

An example of social interaction and relations is provided by a story about a brother and his sister go fishing together (see fig. 23). Small pictures show that the man does certain fishing activities, and the woman gives him a piece of bread. When the boat’s engine breaks, the man tries to fix it. These images demonstrate a stereotypical depiction of relationships between a man and a woman, as well as reflecting social norms about the company that women can keep. The course books do not include illustrations of similar social interactions in English-speaking contexts. The authors focus on business contacts and interaction emphasizing the area where Libyan students are most likely to use this language.

Another interesting observation regarding such relationships within a family and the aspect of socialization can be found in the coursebook (see fig. 24).

The students are provided with some vocabulary to describe family members. The woman is described as a “wife,” but the man is not defined as a “husband” but as a “man.” By the same token, a “wife” could be described as a “woman.” The words “man,” “child,” and “baby” have a strong connotation related to people’s age while the word “wife” unveils the role of the female within a family. This word choice suggests that a man can perform any role in society while a woman can have only one responsibility, which is being the wife. This example reveals the focus on the role of a woman in a family in the Arab cultural context, and it can also emphasize the life cycle while representing pictures for different generations in the family.

Interactions outside the family are represented in the task, Friends of the Mediterranean: 1st Annual Youth Conference, in which several people gather to discuss environmental problems and exchange their knowledge (see fig. 25 and fig. 26). The text provided for reading includes a conversation where students of different cultural backgrounds express their opinion on environmental issues. Students learn various linguistic functions that help them participate in a discussion.

The combination of both Arab and international cultures demonstrates that, despite cultural differences, there are some unifying elements (e.g., handshaking) that help these people build positive social interactions. Smiling is another universal tool that is understood similarly in all cultures. At the same time, such linguistic clues as hello and bye are now understood in different countries among people who have no or limited English speaking skills. Furthermore, the names of football teams known worldwide are also included in the exercise to support the intercultural element and promote the cultural development of English language learners.

Fifth Category: Socialization and a Life Cycle

Category 5 is singled out due to its focus on people’s self-development and relationships between different generations. It is critical to pay specific attention to these rather individualistic concepts as the individual’s identity is mainly built up in terms of their personal growth and development. The interaction between generations is closely linked to family ties that are often the major connections people have. Regarding the dimension of socialization and a life cycle, Arab cultural contents account for 3.9% of examples, 9.5% of examples concern English speaking contexts, and 1.7% of examples relate to non-English speaking cultural contexts.

The concepts of socialization and a life cycle are sensitively higher for English-speaking countries. The attention towards the domain of English-speaking areas is associated with the way the language will be used. The discussion of issues associated with acculturation and personal growth can help students develop proper communication channels with English speakers.

Sixth Category: Behaviors, Routines, Ways of Living, Habits, and Traditions

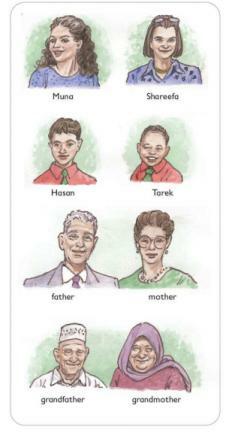

Category 6 is also related to the previous domains, but the focus is on the way people’s self-development and interactions with others are manifested in the form of such artifacts as traditions, routines, and habits. Various types of behaviors, routines and traditions are represented in textbooks for different cultures. The example of the cultural aspect of traditional clothing is given to explain the importance of behavioral changes between generations (see fig. 28).

Three generations of a family are introduced, including a grandfather and a grandmother, a father and a mother, two brothers, and two sisters. The number of children is suggestive since Arab families are often extended with many children. Such patterns are not common in English-speaking contexts. The characters do not look alike, and this lack of resemblance depends on their clothing. The generation of the grandparents is dressed in Arab clothing, which points to the idea of a more traditional behavior of older generations in comparison to younger representatives of the family. At the same time, this image represents a modern family where children are likely to be taught to respect their culture and their beliefs.

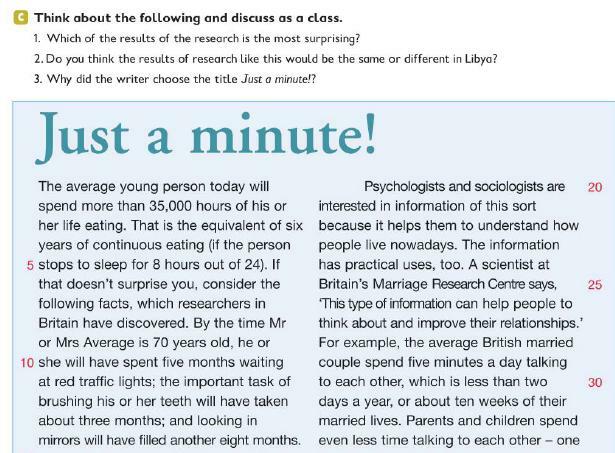

In the analyzed course books, there are also many examples of daily activities or routines related to the English-speaking cultural contexts that allow for understanding how representatives of this cultural context plan their days (see fig. 29). The assignment in figure 29 reveals British people’s routines in the form of statistical data. Importantly, the students are encouraged to analyze these routines in terms of such aspects as communication with close ones. Students are again and again welcome to relate their values to traditions of other countries, which can help them understand these cultural contexts and develop effective communication patterns.

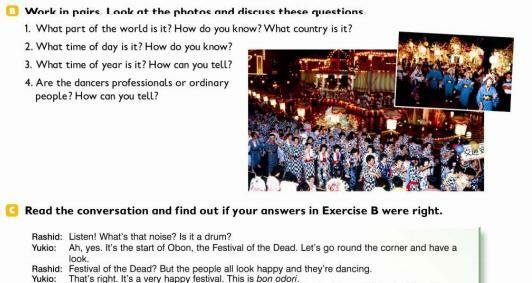

An example of traditions related to non-English speaking contexts is a festival that takes place in Japan (see fig. 30).

The Japanese festival of Obon (the Festival of the Dead) is an unusual spectacle that neither Western nor Arab countries can understand without additional knowledge. However, the authors of the textbook demonstrate a sign of respect for traditions of other cultures. While the focus is on death, the festival is described as a happy celebration, which may be unusual to many people unrelated to Buddhism. Students’ attention is directed to the most conspicuous element of the celebration without addressing the underlying reasons for these peculiarities. The festival is a celebration of family ties and memory as families unite and think about their ancestors. Its links to the religious roots are also omitted, which results in quite a distorted understanding of the festivity.

Many people see such celebrations as Christmas or the Festival of the Dead as traditional festivities rather than an essential element of their religious agenda. In this way, the description and discussion of this Japanese tradition can facilitate learners’ discussion of their own cultures and traditions related to family links, conventions, and so on. The discussion of traditions and festivals seems to be viewed from the perspective of developing the understanding of diversity.

The authors are also likely to juxtapose the Japanese festivity to the globally known Christmas in order to diminish the effects of the American cultural imperialism. The choice of Japan can be deliberate due to the authors’ willingness to discuss a tradition that is very different from festivities common in the Arab or English speaking (or rather the Western world).

At the same time, other festivals that attract a lot of people’s attention and are known worldwide do not receive the necessary attention in the textbooks. For example, the celebration of Christmas in English-speaking countries was not highlighted or even mentioned in the textbooks under analysis. Omitting such significant parts of the life of people about the target culture can be harmful as students will not be able to communicate on the topic that is often discussed in certain seasons in international environments (multinational organizations, international schools, etc.). Moreover, students may develop an incomplete picture and will fail to understand the target culture properly as religion can provide helpful insights into the ways English-speaking cultures developed.

It has been acknowledged that a language is a tool with the help of which it is possible to reflect on cultures. Learning foreign languages means learning about life in another culture, understanding customs, values, and traditions (Tsai, 2017). The challenges of the modern world call for a focus on international contexts rather than one culture. The course books under analysis serve to achieve this goal as the students are exposed to the discussion of global issues and communication in diverse settings.

Seventh Category: Religious Beliefs

Religion plays an important role in people’s lives, especially when it comes to the Arab context. Therefore, it is but natural that aspects related to religious beliefs should be analyzed independently. Category 7 covers the contents associated with religious beliefs. The percentage of examples related to the Arab context is 7.9%, while no specific examples were found for non-English speaking cultures and the English-speaking context. Such aspects as the culture and religion of Libya are properly explained in the text in comparison to the information given about other cultures (see fig. 31 and fig. 32). It is important to focus on the authors’ attention to cultural and religious materials related to the Arab culture. There are no direct parallels with the religious beliefs of other countries.

The task “Think of some examples of Arab culture […] How would you explain them to a person who knew nothing about Arab culture?” is indicative of the textbook’s intentions to develop students’ self-reflective skills and discuss their own cultural preferences. On the one hand, the assignment facilitates the learners’ ability to communicate with representatives of other cultures about their traditions and beliefs. On the other hand, the communication is one-sided as the learners have information about their culture and are not encouraged to ask their partners about other cultures.

As mentioned above, the books under analysis pay significant attention to the development of learners’ self-awareness. However, the lack of attention to other cultures and especially the target culture in such important aspects as religion can be a considerable downside. First, religious beliefs constitute a substantial part of any country’s culture that cannot be understood fully without the attention to this aspect (Bateman, 2011, p. 6).

Moreover, learners’ vocabulary will also be insufficient as they will not have a limited number of words related to this important part of English-speaking people’s lives. The learners will be hardly able to discuss many things including churches, cathedrals, people involved in the religious sphere, and so on.

Furthermore, the development of communicative skills in a foreign language can be facilitated by enhancing or creating students’ willingness to learn more about the target culture (Cakir, 2006, p. 154). The implementation of an awareness-raising approach can “make learners more sensitive to cultural differences and different variables involved in language use” (Kondo, 2004, p. 51). Students should be able to tell about their lives and beliefs and discuss various aspects of their English-speaking interlocutor.

Eighth Category: Literary Aspect

Category 8 represents some of the most valued artifacts of cultures: literary works. Literature has become a way to accumulate and share knowledge among generations, so literary works can provide valuable insights into the way cross-cultural learning takes place when learning a foreign language. This category includes examples where some literary works are discussed, some information concerning famous writers or poets is presented. The frequency of examples related to the Arab culture is 7.9%, the frequency related to the English-speaking culture is 7.2%, and the frequency related to the non-English speaking cultural context is 10%.

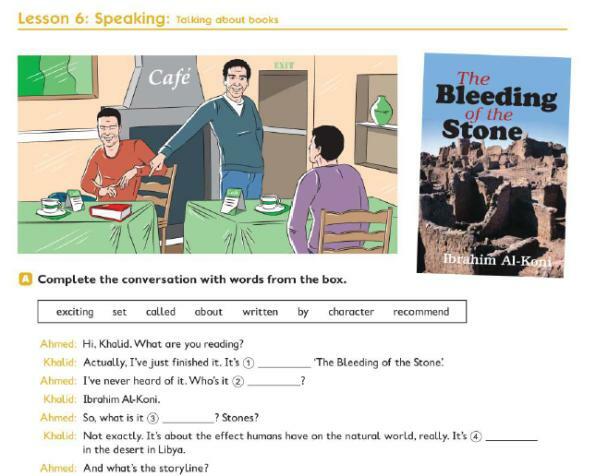

The writers chose to promote the literature of a learner’s first culture before promoting the literature of the target culture. It is noteworthy that the assignment includes a picture of the English version of the book (see fig. 33) although the book is written in English. Decoding the same amount of attention to Arab and English-speaking authors suggests that these two cultures have significant history and play an important role in international education.

Another example good to the point can be observed in the exercises connected with the description of the novel David Copperfield (see fig. 34). This example is particularly relevant because it can be considered as juxtaposing the activity based on the book The Bleeding of the Stone written by an Arab author. The two literary works were written by authors with different cultural backgrounds.

The key goal of language teaching is increasing students’ awareness and developing their curiosity towards the target culture (Cakir, 2006, p. 154). The description of some peculiarities of Dickens’s novel could inspire an English language learner to find the book written in the 19th century and view it as contributing to his or her understanding of English and its specifics. The literary aspect is also related to those exercises that provide learners with opportunities to receive new knowledge and learn how to use new terms in practice

It is noteworthy that the literary works of non-English speaking cultures are not represented at all. This gap is quite significant especially in the domain of cross-cultural training. Learners will be able to draw more parallels between different cultures and link them to their contexts (Dweikat and Schbeitah, 2012, p 15). Students are likely to communicate with people of varied cultural backgrounds, and it can be beneficial to equip them with the necessary skills and knowledge. Bridging the gap between cultures can be achieved through the discussion of some literary works revealing certain peculiarities of other cultures. The textbooks of all levels can contain a literary component, which will enable the authors to provide examples of English literary traditions.

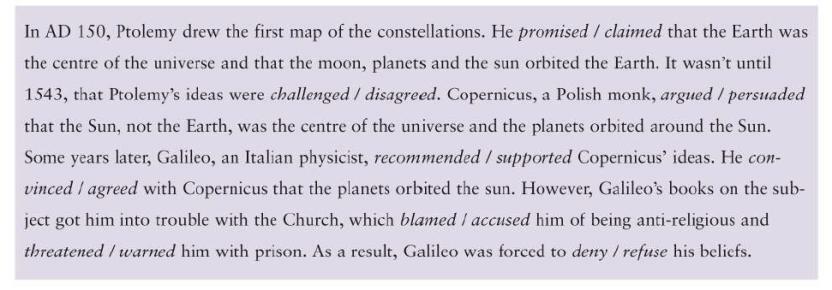

Non-English cultural works are represented a different perspective, with paid attention to scientific advancements that are also an important component of our global culture (see fig. 35). The authors provide valuable facts concerning the way people from different countries contributed to the development of technology and science. Such tasks expand learners’ background knowledge and equip them with the vocabulary necessary to discuss such concepts as technology, science, history, and innovation.

To conclude the analysis of the literary aspect found in the chosen textbooks, it is worth mentioning that this aspect can be especially interesting to students. They can use these exercises to promote additional knowledge and research, as well as improve the current level of knowledge. This effect related to developing cultural awareness is associated with all previously discussed categories.

Discussion

The Representation of Arab Culture Domains

The Arab-Islamic cultural values are dominating themes in the content of all three-course books (see fig. 4). The images of people, places, texts, and contexts reflect the Arab history, community, and cultural perspectives in the first place. The analysis of images included in texts and exercises showed that the authors of English for Libya designed the textbooks with the culture of learners in mind.

As a result, the examples related to the Arab culture help students become aware of the use of English in a cultural context that is familiar to them. The learners are encouraged to discuss various themes related to their everyday routines and values, which facilitates the development of their self-reflective skills. The books help students reveal various aspects of their own culture and share them with other people.

It is noteworthy that even the assignments that had some global cultural contexts were still linked to the Arab culture in some way. For instance, when working on tasks associated with geography or environmental issues, learners are still encouraged to reflect on these concepts within the Arab cultural domain or on their future roles in solving the issue. Students are prepared to use English as the means of communication in various settings and on different levels. Learners are encouraged to discuss diverse topics they can face in their future careers. The authors’ focus on the business domain related to English speaking and non-English speaking context suggests that it is expected that English will be used for business communication.

Representing cultural aspects ranging from family relations to economics, the textbooks include a wide variety of topics to foster adherence to Libya or Arab-specific values. It is noteworthy that some assignments related to the Arab cultural domains are stereotypical. The representation of women needs to be reconsidered as it is mainly viewed in terms of family relations rather than larger social contexts.

Hence, it is possible to conclude that some revisions to the assignments related to the representation of Arab values and traditions may be needed. One of the aspects to address is associated with gender roles and women’s representation. Apart from that, more links to other cultures can improve the cultural component of the textbooks. Learners should be able and willing to draw parallels and discuss the diversity of cultures, traditions, beliefs, and practices.

The Representation of English speaking and non-English Speaking Culture Domains

The analysis of the textbook contents proved that the authors understand the importance of including English speaking and non-English speaking cultures into the discourse to educate students about different social and cultural phenomena (Pratt-Johnson, 2006, p. 1).

A broad intercultural competence is important because it can be used in everyday life during interactions with the representatives of other cultures. It has been acknowledged that textbooks should demonstrate a balance in using examples related to Arab and non-Arab cultures (Allaire, 2014, p. 15). Considering that understanding the cultural heritage contributes to learning languages, and therefore textbooks should refer to the target language cultures (Ellabar, 2014, p. 79), the analysis suggests that this goal was only partially achieved. The images and exercises in the books in question showed that activities related to the Arab cultural context accounted for about 50% of examples. However, the presence of examples related to English speaking (about 21%) and non-English speaking (about 29%) cultures contributed to students’ understanding of culture-specific topics.

To maintain the balance of the cultural contexts within the course books, the authors should reconsider the amount of data devoted to different cultures. A balance can be achieved by achieving the proportion of culture-related exercises at the level of approximately 30%. In this case, the Arab, English-speaking, and other cultures will receive equal attention and can be explored properly. This equal presentation can help achieve several educational goals.

First, students will have the necessary knowledge and skill to communicate on a variety of topics (Kondo, 2004, p 52). Secondly, learners will be able to talk about their culture with people of other cultural backgrounds. Importantly, the sections concentrating on the Arab culture will foster students’ willingness to self-reflect. Thirdly, students will be encouraged to learn more about other cultures, which will have a positive impact on their worldview and their attitude towards diversity.

Furthermore, many important cultural aspects are not covered in the textbooks, thus, not all elements of intercultural competence are addressed. For instance, information about religions is not present. Christmas, as a widely popular holiday, is not included in activities. By the same token, some traditions having religious roots are not discussed in detail. It seems that all religion-related points and concepts are neglected or omitted. Students often have different reasons for learning English. Getting a job or communicating with representatives of other cultures are two common reasons (Al-Hamlan and Baniabdelrahman, 2015, p. 127).

Therefore, these people will have to discuss various topics and respond to many questions, which makes it necessary to include the necessary vocabulary in the textbooks. In addition, due to the contemporary social norms and rules, no attention is paid to the description of Western or international food and drinks that could contribute to representing customs and traditions related to different cultures. Therefore, more examples related to the English-speaking culture are required to guarantee that English can be learned in the cultural context.

It has been acknowledged that language learning is facilitated through the use of assignments related to social experiences (Eldin, 2015, p. 115). The authors provide some tasks aimed at the development of skills needed to participate in interactions with people of different cultural backgrounds. For instance, the assignment concerning the meeting “Friends of the Mediterranean” can assist in the development of communication patterns as well as confidence. However, such exercises are not numerous, which may lead to various barriers preventing learners from using their English in real-life situations. The textbooks can be improved through the inclusion of a variety of assignments replicating different social experiences involving interactions with people about other cultures.

In many textbooks, authors set the goals to educate students on how to treat cultural differences and respect them while accepting diversity related to other cultures. Cross-cultural knowledge is also attained through juxtapositions between the native language and the target language (Gay, 2013, p 49). Still, in some cases, such demands of diversity in language learning have been significantly unaddressed because of the limited number of the provided examples (Al-Hamlan and Baniabdelrahman, 2015, p. 120).

The themes of stereotyping and national identity cannot be neglected because they help students learn something new from different perspectives. Thus, in the textbooks under analysis, the principle of teaching English concerning the context of the cultures related to this language is addressed, but variations in the frequency of examples related to Arab, English speaking, and non-English speaking cultures indicate that non-Arab cultural contexts are underrepresented.

The lack of exercises concerning other countries and cultures leads to the development of a highly stereotypical and rather one-sided representation of these contexts. For instance, when people from non-Arab cultures are depicted only the most conventional images and traditions are highlighted while other relevant details are not mentioned.

For instance, the depiction of people living in English-speaking countries (see fig. 19) reveals some stereotypical views on certain cultures. However, students would benefit more if tips for cross-cultural communication involving these contexts were provided. More importantly, these stereotypes prevent students from paying the necessary attention to diversity as the vast majority of English-speaking, as well as non-English speaking, countries have diverse populations. English textbooks should address this diversity in more detail.

Besides, it is important to stress that the textbooks under consideration can be characterized by biased attitudes. For instance, some traditions are depicted as strange, which can attract learners’ attention, but can create certain stereotypes. The authors do not provide the contexts of these traditions making other cultural values seem very different and incomprehensible. Some domains remain unaddressed although they have considerable value. For instance, tasks associated with literature shed light on some Arabic and English works and authors. Literary traditions of non-English speaking contexts are not provided.

It has been acknowledged that language studies should be accompanied by the discussion of literature as literary works reveal the peculiarities of different nations as well as periods in various countries’ development (Dweikat and Shbeitah, 2012, p. 11). Therefore, the textbooks should contain more examples taken from different countries and epochs. Again, this will help learners in their communication as they will have the necessary vocabulary to discuss different literary works, as well as their impact on the world literature.

In conclusion, it is possible to state that the underrepresentation of different English speaking and non-English speaking contexts can be harmful as learners may have difficulties when communicating with the representatives of these cultures (Bateman, 2011, p. 6).

Cross-cultural components of the textbooks need considerable revision. Although the distribution of tasks and topics seem even, the course books do not serve as the platforms for acquiring cross-cultural competence. In simple terms, the books contain the basic set of vocabulary and facts concerning the primary cultural aspects of people’s lives. Nevertheless, the way the information is given is rather biased. Many tasks contain data concerning traditions from the non-Arab world, and some of these cultural aspects are presented as quite strange and difficult to comprehend. The books could also benefit from the inclusion of more tips on the peculiarities of cross-cultural communication with people from different cultural contexts.

Summary

After analyzing the data, it is possible to state that those elements of intercultural competence that were determined as criteria for the analysis were partially included in the textbooks. For instance, the information related to religious beliefs is not provided in the textbooks for Secondary level 1 and Secondary level 3. Examples of individuals’ socialization and a life cycle could also be added to the text for English speaking and non-English speaking contexts. A limited number of examples were related to the literary aspect. Furthermore, some cultural domains of non-English speaking contexts received little attention in the course books.

Thus, students can experience problems while learning English with a focus on the international context because of the limited knowledge on the matter. As for the exercises related to the Arab culture, the number of such assignments can be reduced to make up a third of the tasks. This amount will suffice for students to help them understand their cultural heritage and the specifics of using language in interactions.

References

Adrian-Vallace, D’Arcy, and Julietta Schoenmann. English for Libya Secondary 2 Course Book. Garnet Publishing, 2008.

Adrian-Vallance, D’arcy, et al. English for Libya Secondary 3 (Scientific Section): Course Book. Garnet Publishing, 2008.

Al-Hamlan, Suad Abdulaziz, and Abdallah Ahmad Baniabdelrahman. “A Needs Analysis Approach to EfL Syllabus Development for Second Grade Students in Secondary Education in Saudi Arabia: A Descriptive Analytical Approach to Students’ Needs”. American International Journal of Contemporary Research, vol. 5, no. 1, 2015, pp. 118-145.

Allaire, Franklin. All Knowledge Is Not Taught in the Same School. Dissertation, the University of Hawaii at Manoa, 2014. UHM, 2014.

Al-Obaidi, Lubna. The Cultural Aspects in the English Textbook “Irag Opportunities” for Intermediate Stages. Dissertation, Middle East University, 2015. MEU, 2015.

Awayed-Bishara, Muzna. “Analyzing the Cultural Content of Materials Used for Teaching English to High School Speakers of Arabic in Israel.” Discourse & Society, vol. 26, no. 5, 2015, pp. 517-542.

Bateman, Blair. “An Analysis of the Cultural Content of Six Portuguese Textbooks.” Ensinoportugues, 2011. Web.

Byram, Michael. Cultural Studies in Foreign Language Teaching. Multilingual Matters Ltd., 1989.

Cakir, Ismail. “Developing Cultural Awareness in Foreign Language Teaching.” Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, vol. 7, no. 3, 2006, pp. 154-161.

Choudhury, Rahim. “The Role of Culture in Teaching and Learning of English as a Foreign Language.” Express, an International Journal of Multi Disciplinary Research, vol. 1, no. 4, 2014, pp. 1-20.

Dweikat, Khaled, and Ghada Shbeitah. “Investigating the Cultural Aspects in EFL Textbooks. A Case Study of the NorthStar Intermediate Textbook.” Scholar, 2012. Web.

Eldin, Ahmad Abdel Tawwab Sharaf. “Teaching Culture in the Classroom to Arabic Language Students.” International Education Studies, vol. 8, no. 2, 2015, pp. 113-120.

Ellabar, Ageila Ali. “Libyan English as a Foreign Language School Teachers’ (IEFLSTs) Knowledge of Teaching: Action Research as Continuing Professional Development Model for Libyan School Teachers.” Journal of Humanities and Social Science, vol. 19, no. 4, 2014, pp. 74-81.

Ford, Karen. “Differentiated Instruction for English Language Learners.” Colorincolorado, 2017. Web.

Gay, Geneva. “Teaching To and Through Cultural Diversity.” University of Toronto Curriculum Inquiry, vol. 43, no. 1, 2013, pp. 48-70.

Halliday, Mak, and Jonathan J. Webster. Continuum Companion to Systemic Functional Linguistics. Continuum International Publishing Group, 2009.

Jernelov, Arne. “The Threats from Oil Spills: Now, Then, and in the Future.” Ambio, vol. 39, no. 5-6, 2010, pp. 353-366.

Kondo, Sachiko. “Raising Pragmatic Awareness in the EFL Context.” Sophia Junior College Faculty Bulletin, no. 24, 2004, pp. 49-72.

Liu, Yi-Chun. “The Use of Target-Language Cultural Contents in EFL.” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, vol. 4, no. 6, 2014, pp. 243-247.

Macfarlane, Mike, and Richard Harrison. English for Libya Secondary 1: Course Book. Garnet Publishing, 2008.

Marsiglia, Flavio, and Jamie Booth. “Cultural Adaptation of Interventions in Real Practice Settings.” Research in Social Work Practices, vol. 25, no. 4, 2014, pp. 423-432.

Napier, David, et al. “Culture and Health.” Lancet, vol. 384, 2014, pp. 1607-1639.

Paige, Michael, et al. “Culture Learning in Language Education: A Review of the Literature.” Carla. Web.

Pratt-Johnson, Yvonne. “Communicating Cross-Culturally: What Teachers Should Know.” TESL, vol. 12, no. 2, 2006, pp. 1-3.

Spencer-Oatey, Helen. “What is Culture? A Compilation of Quotations.” Warwick, 2012. Web.

Taguri, El, et al. “Libyan National Health Services. The Need to Move to Management-by-Objectives.” Libyan Journal of Medicine, vol. 3, no. 2, 2008, pp. 113-121.

Tsai, Jeanne. “Culture and Emotion.” Nobaproject, 2017. Web.

Appendix A

English for Libya Secondary 1: Course Book.

English for Libya Secondary 2: Course Book.

English for Libya Secondary 3: Course Book.