Abstract

A cross-cultural project team is composed of members with different cultural background, and who also speak different languages. Communication involves a process of sending and receiving messages. How a team effectively communicates and pursues its mission and objectives amid cultural differences of the members is the main objective of this dissertation.

An important part of this paper is about project management. A project is about work and project management is managing people at work.

How does communication play a key role in a cross-cultural project team?

First, definitions were provided. Various authors and experts in the literature about project management, strategic management, and organisations existing in the global arena of business, were consulted and their ideas and opinions were embodied in the literature review. Qualitative and quantitative analyses were also used for this dissertation.

The Arabtec Construction Company of the UAE is used as a case study. Project managers and members of the project teams of Arabtec were requested to be participants of the survey. The Arabtec workforce is composed of professionals and workers from the Emirate states, but many of them also come from the different parts of the world, with different cultural backgrounds, languages, and cultural biases. A big percentage of the population of the UAE is composed of immigrants and expatriates from India, Pakistan, the Philippines, Europe, some parts of Saudi Arabia, and many other countries in Asia (Arabtec Construction, L.L.C.: about us 2011).

The survey used questionnaires submitted to the participants from Arabtec, who provided their answers to the questionnaires sent them through emails. Analyses of the participants’ responses formed the main part of the Results/Analysis section of this paper.

The participants’ responses were assigned codes in what is termed codification. These codes are words or phrases that represent the responses. The codes were embodied in a table to describe the frequencies, or the number of times they were used by the participants. This process can present a picture of how the participants, who represent the various project teams of Arabtec Construction Company, have prepared to meet the challenges as members of the cross-cultural project teams.

Introduction

Communication is a word with many meanings. We take the meanings one by one so as to avoid inconsistencies, and take note on the most important one – communication and its role in a cross-cultural project team.

Project success is a product of many factors. The most important is careful and honest planning and implementation of business strategies, but above all, teamwork. A team is a part of a whole, the organisation. While it focuses on the project, it has to emphasise the organisational goals and objectives. A team cannot create teamwork without effective communication.

The program of project management is part of strategic development of an organisation. Strategies, or techniques, and their applications are important factors to the success of projects (Fisher 2006).

Strategic management is about change and issues on strategic development and change in organisations. It focuses on the organisation’s mission and objectives, and addresses external factors, like competition, customer requirements, technology and regulation, and creation of a structure, while employing all possible resources of those strategies. All these require an effective communication process that flows through every department and section of the organisation. (Thompson 2005)

Dealing with organisational strategies

The plan of action for strategic management includes: positioning the company strategies to provide the best defense against competitors; influencing the balance of forces by means of strategic moves; and, anticipating the changes in the various forces while exploiting a change for the new competitive advantage before competitors gain the chance to be ahead of the race. (Porter 1998)

A strategy is effective when it is able to identify the strengths and weaknesses of both sides. It is almost similar to any other competition.

Aims and Objectives

The aim of this dissertation is to identify the role of communication in the success of a cross-cultural project team.

The objectives are:

- To define communication in the context of the multi-cultural teams of Arabtec Construction Company;

- To determine the responsibilities and challenges of the project manager and the members of the team; and

- To define the circumstances surrounding a multi-cultural project team and organisation.

- To analyse the role of communication using the case study, Arabtec Construction Company.

Research Questions

- What factors affect communication in a culturally-diverse team or group?

- What cultural differences exist amongst managers and employees of Arabtec Construction Company?

- How can cultural integration be introduced within a cross-cultural project team?

- How effective is communication, and how is it managed, within project teams of Arabtec Construction Company?

Literature Review

Communication: concepts and significance

Various factors play a key role in effective communication within a cross-cultural project team. Communication’s role is to provide an exchange of information. It’s very important in our personal lives and professional careers, but most especially, in every human interaction. Communication is a two-way process; it is never a one-way process. There has to be a sender and a receiver of message, or messages. As the sender sends a message, he/she expects a feedback. That is the normal process; if there is no feedback, the sender will assume that the message was not received by the receiver (Rad and Levin 2003).

Communicating and sending a message is not just a circumstance or situation, it is a process. The success of this process depends on the parties and how these two parties deal with environmental factors, or barriers, that affect the process.

In a multi-cultural project team, communication may be a difficult process. Culture impacts on effective communication within a team. But, as said, it always depends on the members of the team, in their communication skill and openness to send and receive messages within the team, and eventually, within the organisation. The application of a system where communication is easily understood is also vital in the success of a multi-cultural project team.

Communication and cooperation are important in obtaining group trust. The members should endeavor to reduce uncertainty in group activities. Studies have found that training plays an important role in reducing problems and conflicts in cross-cultural groups or teams (Cragan et al. 2009).

Some researchers/commentators indicated that new project teams, or the teams of the twenty-first century, have been simplified. Project teams are a bit smaller compared to the past, and with simplified structure. Team members are expected to be skilled in problem solving, to be creative and independent but can work as efficient collaborators among the different groups of the organisation. (Burdett et al. 2008)

In this age of advanced technology, teams can be separated geographically and the multi-cultural set up is still very much present. This orientation demands a very effective communication process. The Internet and other information technology tools are some of the means to provide an effective communication process (Doerry et al. 2001).

Creation of virtual teams is one revolutionary method as a result of the Internet and Information Technology. Team members can be separated geographically, or by time. Here, relationship is difficult to attain because the entire team cannot be brought together face to face. Culture is a problem (Clutterbuck and Hirst 2002).

This type of project team is becoming a trend particularly in multinational corporations.

Project and project management

Background

Project management was first introduced in construction and engineering and has been borrowed by other fields because of the benefits acquired by organisations. It has been applied to other fields such as academic, industrial, service, and other professional tasks.

Great leaders of history were good project managers. In the 1950s, project management was first used in an informal sense in the construction of infrastructures. It was also used in social and political constructs. However, it was only in the 1960s that a great amount of literature was poured in by researchers describing the advantages of project management. Early managers did not consider project management as too important to influence organisational activities, but project management played a key role in the success of major projects (Cleland 2001).

The Great Pyramids of Egypt, the cathedrals and mosques of Europe, and many other infrastructures, were all constructed with some form of project management. The old churches, which are considered heritage sites, were built with what we can consider excellent project management. We can see for ourselves about 500 large churches built between the periods 1050 and 1350, and about 1,000 parish churches also guilt with such ingenuity and fine works of art (Swarbrooke 2002).

In the 1970s, there was a rapid growth in Information technology, or IT. Industrial project management continued as before, but with more project management software available and wider recognition of the role. However, the spread of IT brought another different kind of project manager on the scene. These were the IT project managers: people who had no project planning or scheduling experience and no interest or desire to learn those methods. They possessed instead the technical and mental skills needed to lead teams developing IT projects. These IT project managers were usually senior systems analysts, but they were only few in this trade (Lock 2007, p. 3).

Successful outcome of projects requires some investment on the part of the organisation; thus it is obligatory on the part of the managers to see to it that the project is well planned and executed. This is how important project management is to an organisation or a group implementing certain projects. There are several well-known cases where, for example, failure to implement a new computer system correctly has caused serious operational breakdown, exposing the managers responsible to indignity. Effective project management is at least important for these projects as it is for the largest construction or manufacturing project (Lock 2007, p. 7).

Concepts and theories

The PMI Standards Committee, through its guide, known as Project Management Body of Knowledge, defines project as something that involves work, either as operation or project, but which is done by people, has limited resources, and is worked with a plan, execution and control (Verzuh 2012). Project management is about processes with goals, from start to end, as required by the customer (Carden and Egan 2008).

Practically, no organisation operates without a project or activity, and this project has to be managed by a well-trained manager, who knows how to act in situations that require immediate and precise decisions. PMI’s definition emphasizes the uniqueness of a project. A product or service may have a wider scope but it has to be unique in every aspect.

A project, on the other hand, is a job or task that is carefully planned, with a deadline, and implemented by a team, to be evaluated by a manager or client who is the owner or buyer of the project (Carden and Egan 2008).

Project management suggests that it has to manage stakeholders; meaning management and plans for stakeholders should be developed. There might be stakeholders who oppose the project because of the impact of the project (Boehm and Jain 2007).

In this case, diplomacy and tact are needed in negotiating stakeholders who oppose. If matters don’t get resolved, it is important the project organisation consult a higher authority, or acquire the services of external individuals in resolving the issue (Guidance on project management: International Organization for Standardization 2011).

There are four historical stages of project management: first is its discovery; later, it is refined and improved by the users; then, it is used in human resource which creates a beneficial outcome. Human Resource Development (HRD) managers who do not recognise the importance of project management fail in planning and management of their projects (Gilley et al. as cited in Carden and Egan 2008).

Relationship of Project Management to other disciplines

HRD and project management are related. HRD uses project management techniques such as planning in implementing projects. Activities are geared towards improvement of the organisation and also for the individual. These activities are aimed and classified as projects, implemented by a project team. This method has become common in many organisational activities worldwide (Rodriguez & de Pablos 2002).

Project management and HRD enhance careful project planning. Both strategies provide avenues for improvement and fulfillment of the organisation’s objectives. They can also provide positive output for the organisation (Pattanayak 2005).

Effective management focuses on people. The manager and his team must work as a cohesive force, and should be flexible in satisfying the customer’s needs and wants (Gulati and Oldroyd 2005).

Organisational strategies are based on organisational mission, vision and policies. Projects are the means in which organisations attain their goals. Strategic goals provide a framework for the creation of opportunities (Armstrong 2000).

Opportunities should be selected based on the benefits gained and management of risks. The project goal is the measure for chosen opportunities. The project objective adds more meaning to the project goal by providing the deliverables. When the benefits are realised, project goals are accomplished. This requires time as the objectives are already set (Guidance on project management: International Organization for Standardization 2011, p. 9).

Responsibilities rest on the hands of the project managers, albeit project managers also depend on team members’ cooperation and teamwork. The manager also determines the number and type of employees needed in his team and where labor supply must come from (Harris et al. 2003). S/he must see to it that recruitment, training and development and assignment of people are all in accordance with the organisation’s objectives. Existing employees can be trained, developed, redeployed, transferred or promoted for future skill needs. New recruits should be carefully selected to ensure suitability for future positions (Raman and Watson 2004).

The staffing process should be in line with the organisation’s objectives. The manager should see to it that recruits are qualified (Armstrong 2000). The staffing requirements emphasise the skill and capabilities of applicants (Miller 1984).

Project management is now a major aim of organisations. Project managers play a significant role in organisations because of the importance of projects in the organisation’s goals. Researchers find project management an interesting subject of research. Not only is it important to organisations but it affects organisational objectives. Successful projects require investments, in time and resources. It is the responsibility of project managers that projects are well planned and executed (Lock 2007).

There are different projects undertaken by industries and organisations. Turner (as cited in Blomquist and Wilson 2006) indicated that projects can be classified according to how well methods and goals are described and applied. For example, in engineering, projects can be well defined by describing the methods and goals of the project. Successful projects are planned according to quality, cost, and timing. In contrast, projects for change have a high degree of failure. In this kind of project, a soft-systems approach is applied wherein judgments are applied at key points whether to continue or stop the project (Ajami et al. 2006, 41).

Philosophy behind project management

Project management has come to mature as a part of the organisation’s major activities. Because of this, its philosophy has some distinct characteristics. Project management is a means to facilitate production and delivery of products and services, and to introduce change in organisations (Ryan 2004, p. 11).

Project management leads to the formation of teams and the introduction of reengineering, benchmarking, and other activities for improvement and development of an organisation. Project management encourages planning, organising, and teamwork, and motivates growth in professional associations.

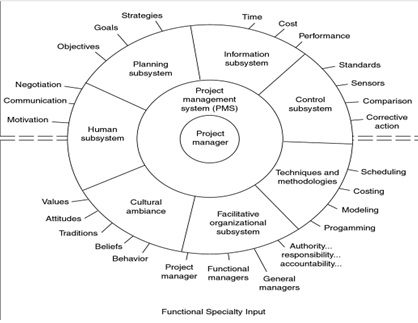

The major activities in project management are demonstrated in the following Figure 1.

More uses of project teams have been in the fields of marketing and marketing assessments, competitive assessment, strengthening of organisations, benchmarking, improving organisational standards, accomplishing goals and objectives, and much more.

Planning

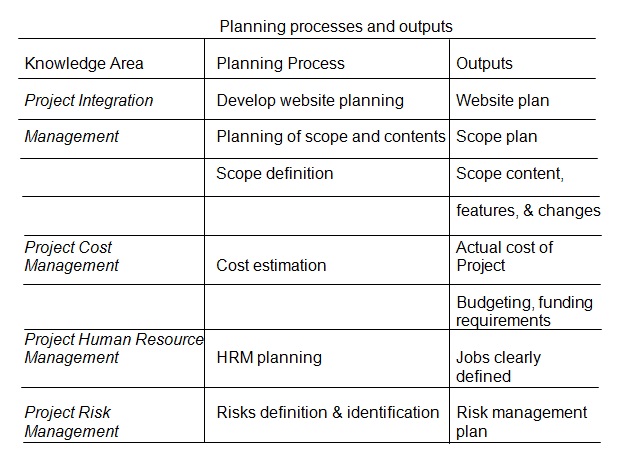

Project planning and team building are important significant activities in project management. A combination of an outstanding team and a well developed plan results into a successful project. (Thomas et al. 2008, p. 105) Knowledge, teamworking and good management are important for the success of a team (Koch 2004). Through planning, risks are identified prematurely, thereby eliminating ambiguity and uncertainty in the team’s activities (Zwikael 2009, p. 95)

Importance of Planning

Studies have shown that when planning processes are developed and improved, there is a likelihood of success. Planning is the key to project success and is a critical success factor to project management. The goal of the planning phase is preparation for the actual project execution and control (Zwikael 2009).

Cost and scheduling are significant factors to planning (Flyvbjerg et al. as cited in Zwikael 2009). This was noted in a study involving a $90 billion infrastructure project which found the cost estimates to be misleading. Cost estimate and benefit analyses have to be meticulously done during pre-planning phase as it could lead to “overruns” (Keil et al. as cited in Zwikael 2009, p. 95).

The main concern of project planning is to get decisions for the project that should be implemented in the future. Project planning provides a step-by-step process for the project team, which tells them to do the necessary and important ways of doing it, how and when to do it, and the resources that should be used in order to deliver the desired outcome of the project (Meredith and Mantel as cited in Zwikael 2009).

Through quality planning, project managers can have: elimination and reduction of uncertainty; improved efficiency of the operation; an understanding of the aims and objectives of what the planners are doing; and a basis to maintain the momentum of work (Kerzner as cited in Zwikael 2009).

On the other hand, strategic planning is implemented by firms to increase new product development (NPD) that can enhance organisational performance. Strategic planning refers to the organisation’s strategy in dealing with the competition in the industry, while project planning is implemented on a particular project. But the two are interrelated because they are applied for organisational success (Song 2011).

Communication, including negotiations, between the team and the various stakeholders is necessary to reach a consensus. Over-capacity loads can be reduced, and some special strategies can be introduced (Weinreich 2007).

Pre-Project Planning

This phase encompasses all the tasks before the designing and the initiation of a project. Needs and requirements of owner organisations have to be identified since this is critical in the life cycle of the project (Barrie & Paulson; Pena and Parshall as cited in Gibson and Gebken 2003). Unfortunately, many organisations lack the necessary pre-project planning activities (Federal Facilities Council as cited in Gibson and Gebken 2003). A pre-project planning’s major task is the development of project scope. Project scope is defined as the process wherein ‘projects are defined and prepared for execution’ (Gibson and Gebken 2003, p. 347).

Weinreich (2007) suggested cost planning. This may be done after the project targets and the time plan mentioned above. The project manager/team leader, along with his/her core team, can employ the methods of budgeting and cost planning so that prospective expenditure and possible risk can be controlled (the risk factor can be minimised). If there are deviations, as the project becomes in full swing, they can be controlled (Edmond 2002).

Project planning and team building

Planning is sometimes difficult because it requires a lot of imagination and creativity for something that is not yet tangible. It is still an idea, fresh in the imagination of the planners and has not yet been concretely perceived or seen.

There are various models used in the planning and execution of projects, which can be on a case-to-case basis. Project managers use the basic technique, the “Gantt-chart” method, which states the tasks and milestones of the project and provides the timing and a degree of certainty forecast. There are also other approaches that have evolved from this method, such as the “state-gate” (Cooper), “waterfall”, “spiral”, and “helix”. State-gate is applicable for projects involving lots of product development, but the others are important in the planning and implementation of IT projects (Blomquist and Winston 2006, p. 208).

Project planning and team building are important significant activities in project management. A combination of an outstanding team and a well developed plan results into a successful project. (Thomas et al. 2008, p. 105) Knowledge, teamworking and good management are important for the success of a team (Koch 2004).

The Cross-cultural project team

A team is defined as a group of individuals, workers who are dedicated to devote their skills and time for a common goal, and for which they bind themselves to commit. The team works for the development of a particular product and service (Carden and Egan 2008).

Organisations and businesses are now composed of managers and employees of different nationalities. It is believed that expatriate employment has decreased after the September 11 terrorist attacks against the United States, but survey results revealed that expatriate employment was continuing to increase (GMAC Global Relocation Services as cited in Littrell and Salas 2005).

Firms want employees who have knowledge, skills and capabilities to lead a team, and not on what ethnic group they belong. Moreover, because of globalisation, organisations, no matter how big and how small, are affected by other organisations and businesses around the world. The attitudes, values and behaviours of the people within the organisation are affected by different cultures (Swarbrooke 2002).

The first time a multicultural team is set up, cooperation and collaboration are difficult to attain because of ethnic and national differences. This risk can be countered when discussion and sharing of ideas are conducted among the members of the group. All members of the team have to commit themselves to this initial undertaking (Maude 2011).

When teams are formed, managers and team leaders have to be discreet and alert. A team is defined as a group of individuals, workers who are dedicated to devote their skills and time for a common goal, specifically for an organisation, and for which they bind themselves to commit. The team works for the development of a particular product and service. This product and service belong to an organisation where the individuals work (Caden and Egan 2008).

The individual members are highly interdependent with the other members, yet all are geared towards the achievement of a goal or the accomplishment of a task. Team members are all agreed on a common goal and work together for the fulfillment of that goal. There are many teams out there not working as teams because they don’t work for a common goal. The ultimate requirement for the team is the interdependence of the individual members (Parker 2003).

The objectives in establishing a team must first be formulated. A selection of team members begins by referring to the list of skills, abilities, and experiences needed for team members in the charter. The team develops a membership matrix listing all the needed qualifications and the prospective qualified applicants or members. The members have to be screened by a responsible person, or the manager.

Teamwork and team building

Teamwork is considered a special feature for improved organisational performance. The formation of teams can be considered the result of the implementation of total quality management, which is essential for organisations dedicated to the development of workers (Contu 2007).

Team working is also known as “lean factory”, which means reducing to simple teams to produce results. It was first introduced in the automobile manufacturing industry, an industry that needs a lot of teamwork, cooperation, and skill on the part of the workers (Contu 19906).

Lean design aims to minimise waste and repetitions on the job, and to reduce production costs. Products are only delivered when ordered by the customer or, in the case of business-to-business (B2B) arrangements, by another company. There is no excess in supply or supply inventory. The system is fast and effective and this is what lean design aims for (Knights and Willmott 2007).

In any activity for any industry, team building is important. A project team essentially needs teamwork to be successful. Team building must be constantly practiced in the office or in the workplace. To be a part of a team is innate in human beings; therefore, humans are already team builders (Parcon 2007).

Multi-cultural project teams have to adjust with the different cultures of individual team members. Members have to adopt with the organisational culture and the cultures of each of their co-members.

Culture and cultural differences

Human interaction among peoples of diverse cultures can be traced back in pre-historic times. These cross-cultural relationships however, were not recognised until after World War II. This phenomenon occurred chiefly within the United States because its economy was not very much affected during the war. The United States developed a plan, known as the Marshall Plan, to help rebuild countries devastated by that world war. The success of the plan enabled the United States leaders to create international development efforts for multi-diverse groups. In addressing intercultural needs, leaders and members of teams and organisations have to be prepared to function effectively with strange cultures in the course of business (Pusch 2004).

Cultural barriers become complicated for projects executed in foreign countries. The project team needs to deal with stakeholders, or people of different cultures. Cultural barriers will have to be dealt with on the different aspects of management, like the middle or top management, or even at the lowest level (Magoshi and Yamamoto 2009, p. 446).

Comparative human resource management and international HRM are two common factors that help in the understanding of cultural differences and awareness. Boxall (as cited in Brewster 2002) indicated this and made it interesting in the topic of HRM. Comparative HRM is a way to explore HRM functions in different countries.

Culture is common to a particular group of people who speak the same language, in a particular time period, and in a definite geographic area (Triandis 2002, p. 16). Culture includes all activities that characterise the behaviour of particular communities of people, such as legal, political and economic factors. Nationalism and dealings with governments are often considered major problems facing a firm trying to sell overseas. Most governments play either participating or regulatory roles in their economies (Jobber and Lancaster 2003).

Kroeber and Kluckhohn (as cited in Rosenhauer 2007, p. 15) indicated that culture has many definitions, about 200 of them. The most popular is that by Hofstede, which states that culture is ‘the collective programming of the mind’, distinct for one group or groups (Mead 2005, p. 8).

Culture can refer to music, the arts, literature, or how people live and interact. In ancient times, people sing and dance as they heal the sick, a way of cultural expression (Celaya and Swift 2006, p. 230).

Global organisations work in a multi-ethnic environment, which is a base for diverse cultures, and greater cultural divide (Bond 2003, p. 43). There are two cultures in a global organisation: the organisational culture and the culture of the host country. National culture influences organisational practices and behaviours and perceptions of the workers (Smith et al. as cited in Fischer et al. 2005). These two factors influence and pose a great challenge to expatriate managers and workers.

Managers and employees assigned in foreign countries experience culture shock. Culture shock is a challenge for expatriates when working in subsidiaries or in foreign countries. Expatriates have to adapt to a new country with a new culture, a new social organisation, and a different way of doing things (Katsioloudes & Hadjidakis 2007).

Culture includes values, beliefs, practices, behaviour, and tradition. A people’s past can be identified through their culture (Kalman 2009). Culture is a powerful force that affects managerial values in different countries (Ottaway et al. as cited in Robertson et al. n.d.). Cultural integration is a problem but can be countered through training and orientation. (Thite et al. 2009)

The project manager and team leader

The project manager has a big responsibility in attaining cooperation and interaction among the members of a culturally-diverse team. The manager can inject a common focus and purpose for each individual member to cooperate. He/she has a job to motivate his people (Locke 2001).

During the first weeks of the team’s existence, the project manager and the members have to face difficulties. Relationships are still beginning, routines have to be established, and expectations of individual members are not yet clear. The ways individual members respond to leadership are unclear because of differing cultural backgrounds (Maude 2011).

In this situation, communication plays a vital role for the team to maintain unity. The communication process is affected but, on the contrary, it can be used as a tool for the team’s unity and effectiveness.

As a manager of a diverse team, a team leader must have flexibility in dealing with cultural differences. Different cultures have their own way of business and interpersonal relationships. For example, Japanese employees are motivated by what they call “failure feedback” from their leaders/managers, while Canadian employees positively respond to success feedback (Heine et al. as cited in Maude 2011, p. 102).

The project manager must first organize the team, and must have a sponsor or a customer. He has to formulate the steps of the project life cycle, and determine the objectives, vision, and priorities of the project. (Kendrick 2010)

The project manager must have in mind the customer’s satisfaction of the team’s job. The project team’s performance is measured by the customer, and it will reflect on the organisation’s performance and integrity. (Gido and Clements 2009)

Project managers should learn relevant customs and business protocols of other countries. Geert Hofstede (as cited in Verma 2001, p. 466) emphasised that project managers should master the dimensions (power distance, uncertainty avoidance, etc.) of national cultural differences to be effective in managing a culturally-diverse project team (Verma 2001).

Effective leaders must appropriately respond to the demands of specific situations. A leader can be demanding and understanding at the same time; emotions are not a part of his/her management style. There are times that a leader has to relax and wait for comments and suggestions. But he has to be decisive in some situations. It is an important characteristic of a leader – to make decisions in compromising situations. But what occurs most of the time is a group decision. A collective decision between the leader and the members is a compromise and win-win decision for the cross-cultural project team. This, in a sense, occurs only when there is effective communication within the team.

A charismatic leader can influence the members of the team to respond to various complex situations. He can make negative situations positive and influence the thoughts and feelings of the members to be cooperative. A leader knows how to deal with change. Change is a challenge for the leader and the team. Change is a complicated part of this wholesome and mean world which the project team must encounter (Tarique et al. 2006, p. 208).

Training and Development

Training and development is an important ingredient for project success. It must be an integral part of the objectives and strategies of the organisation to enhance communication among members of a multi-cultural project team. Training and development serves to shape the workforce (Jackson et al. 2009, p. 304).

Cultural awareness training teaches people to understand other cultures and their own cultures too (Griffin & Moorhead 2007, p. 484).

Training and development should be an integral part of the objectives and strategies of the organisation to enhance communication among members of a multi-cultural project team. Diversity training is one aspect that needs focus in addressing the problem of cultural integration. Training people from different cultures to work together is a significant activity (Jackson et al. 2009).

Communication and cooperation are vital in obtaining group trust. Communication training – to be done in small groups – can reduce cultural conflicts. Trust building and team building are important training subjects. Managing conflicts must be a part of training, for it can help in allowing members of cross-cultural teams to be cooperative and contribute to the success of organisational objectives (Cragan et al. 2009).

Cultural awareness training method focuses on the culture of the participants. It must be designed to teach the participants how their own culture differs from the cultures of other employees with whom they work. The meaning of culture here would refer ‘to the social group to which a person belongs’ (Jackson et al. 2009).

Intercultural training can improve intercultural relations. It provides effective communication among the members of the team or organisation. It provides interdisciplinary focus on various disciplines such cultural anthropology, cross-cultural psychology, and various aspects in international business. (Bennett et al. 2004)

Importance of Cross-Cultural Training (CCT)

The three important factors in effective communication are knowledge, skill, and motivation. Relationships among peers depend on the individual knowledge among members in creating diversity and improving communication skills (Cragan et al. 2009).

As globalisation is becoming more intense, cross-cultural training and understanding is now a necessity (Fowler and Blohm 2004). Cross-cultural training helps expatriates by enhancing their adjustment awareness (Black and Mendenhall as cited in Puck et al. 2008). Firms should choose which programmes or courses their managers must undertake. CCT must include methods in which expatriates’ knowledge of the host country’s culture is enhanced (Celaya and Swift 2006).

Instruments in intercultural training

Instrumentation is vital in intercultural training. Instrumentation refers to “testing” or “inventory”. An instrument refers to a certain kind of measurement for a group or organisation. It evaluates the cultural characteristics of groups or organisations. (Reddin as cited in Paige 2004, p. 86)

Instruments help trainers attain their objectives, improve their activities and efficiency, or sharpen their training design. Moreover, instruments are for assessing trainees’ personal development and the organisation as a whole, analyse audiences, explore cultural and ethnic issues, among others. (Puck et al. 2008, p. 2183)

Cross-Cultural training methods

Project teams have to undergo cross-cultural training before working on their projects (Fowler and Blohm 2004). Cross-cultural training can start with regular briefings through the company’s reading materials, or magazines and informative materials about the country of destination, and about the project team’s orientation. Similar activities include departure orientation and socialization in the host country.

Structured lectures that includes employ multi-media, films, field trips, even simulation exercises, are also useful. An effective way is the integration of the various methods that allow the participants to interact and move from a simple to a more complicated level of learning. Cross-cultural issues cover many fields in human resource management. This includes recruiting, retaining, and motivating employees to love their job, be creative in the process, and do all they can to make the project a success (Bhattacharyya 2010).

The study of Celaya and Swift (2006) on US managers assigned to Mexican cultures found that meetings with experienced international staff were the most commonly experienced type of training. The second most common type was lecture training. Team group training, modeling, and assignments to microcultures had not been experienced by any respondent. They also found that training cannot fully develop intercultural understanding for everyone, and that there are other factors other than training that influence US managers’ understanding of Mexican culture (Celaya and Swift 2006, p. 240).

Important contents of a cross-cultural training include cultural identity; the business of the team affected by the particular culture; how to explore and deal with the identified culture; aspects and forms of global communication; world religions; immigrants from around the world; and, identity of the country of destination (Bhattacharyya 2010, p. 105).

Field experience

Social learning theory takes the point of experience as a way of improving one’s self. Ilgen et al. (as cited in Celaya and Swift 2006) argued that experience is an effective way of training, in inculcating in the minds of the participants cultural differences and barriers of a country.

Field trips

In this type, managers and employees target a country where the company has a branch, and the staff of the organisation provides first-hand appreciation of the culture and ‘way of life’ of the people in that country. This method is expensive but effective, in some way.

Experienced international staff

A way of training is meeting with an experienced international staff, which can happen within the premises of the company where learning and understanding is easily passed on, and information is obtained from the experienced staff. The experienced staff can provide a clear view of what would soon happen in the country of destination for the expatriate; they can present advice, framed within the context of the organisation (Siponen et al. 2007).

Some other ways of CCTs include lecturing or orienting the manager about the host culture and assuming that the manager could cope with the new culture. A culture-specific training assumes that the manager is trained and prepared for the new culture. Another is self-awareness which assumes that understanding and accepting oneself can also be a way of measuring how he/she accepts another of different culture (Ajami et al. 2006).

Training programmes

As stated in the previous section, various considerations must be taken before training must be conducted.

Training has to include different methods and strategies in acquiring knowledge, including product knowledge and an appreciation of the company, its history and philosophies. Language is important and familiarity of business protocols.

Members of the project team should learn to appreciate the language, lifestyle and culture of the people. The trainee has to undergo the different barriers in a cross-cultural project operation. After all, it is first and foremost, a project operation. Then, the team members have to integrate or compare their own culture with the organisational culture and the country culture.

Training must include knowledge of the organisation. It is about the brief history of the company, how it has grown and the organisation’s mission. Policies relevant to the selling function, for example how people are evaluated, and the nature of the compensation system will be explained. The way in which the company is organised is described and the relationship between sales and the marketing function, including advertising and market research, are explained so that the employee has an appreciation of the support he or she is receiving from headquarters (Ryu and Parsons 2008).

Product knowledge includes a description of how the products are made and the implications for product quality and reliability, the features of the product and the benefits they confer on the consumer. Other features of the training programme include establishing good habits among the trainees in areas which, because of day-to-day pressures, may be neglected (Ryu and Parsons 2008).

The lecture method is useful in giving information and providing a frame of reference to aid the learning process. This should be supported by the use of visual aids, for example professionally produced overhead projectors and other Information Technology materials. (Jobber and Lancaster 2003)

Managers should have a formidable set of skills in order to perform their jobs efficiently, including teaching skills, analytical skills, ability to motivate others, communication skills, and the ability to organize and plan.

Challenges global project teams face

In the age of intense globalisation, phenomenal changes and innovations are continuous. The world of business is constantly facing new innovations and applications, thus organisations have to cope with constant change. Project teams have to operate in different locations

Project teams have to operate in different locations, sometimes in distant and multiple locations (Schott 1989, p. 12). Members of the teams have to constantly travel and have to work in a culturally diverse environment. Communication strategies have to be very effective, and the members have to be well versed in communication skills. (Binder 2007, p. 2)

Project teams have to work not only for one department or company but for several departments or companies. The team managers and the members have to adjust with the multiple policies and procedures, including the diverse cultures of the individual members (Pritchard 2004).

Another challenge is the culture of the country where the organisation or project team is operating. Culture includes customs and traditions, which greatly affect the work environment and the manner in which business is managed (Binder 2007). Organisational culture is another built system, influencing the values and behavior of employees.

The presence of change must encourage team members to express their talents and creativity. Change can influence decisions but it must be for the better and can be a lesson for future decisions (Sussland 2000).

According to Burnes (2004), change is always present in an organisation. In these times, we feel more changes now than before. It’s the feeling that allows more changes. Kurt Lewin (as cited in Burnes 2004) introduced the term “planned change” to distinguish what is only accidental or the result of an impulse. Planned change, as the term implies, relate to organisational development, where managers and employees work as a team to introduce change and improvement in an organsation (Ostenfeld 2006).

Motivating members of the team

Organisations have to motivate their people, which can be in the form of monetary rewards, benefits, and promotions. Performance of employees can be enhanced through motivation programmes of the project team (Luecke and Hall 2006).

Motivation and goal setting vary in different organisations and countries. Workers of different cultural background are motivated differently. According to a study by Audia and Tams (2002), goals and performance also vary of employees vary because of their cultural background. People have to be motivated and allow them to feel that they are important to the team (Locke 2001). Maslow’s motivational theories on the hierarchy of needs have been introduced in project teams. It has also been introduced in training programmes (Maslow 1943).

Case study: Arab Technical Construction Company (Arabtec Construction L.L.C.)

Arabtec is one of the UAE’s major construction companies in the Middle East whose mother organisation is Arabtec Holding Group. Arabtec is involved in building hotels, airports and terminals, residential houses and villas, and other large constructions in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. It has a number of associated companies, mostly involved in the construction business, but also in allied industries like heavy equipment, engineering services, steel manufacturing, etc. (Arabtec Construction, L.L.C.: about us 2011).

Arabtec Group had its initial public offering in 2004. Arabtec Construction is the sole construction company in the UAE. It has two contracting arms operating in Abu Dhabi and Dubai, and a diversity of projects, from residential to commercial, including industrial and leisure projects. Arabtec has a 30% share in the Burj Dubai building. It has committed to large expansion strategy since the early 2000s. This expansion includes a versatile and professional labor force, and technical and logistical aspects (Oxford Business Group 2007, p. 90).

Its recent workforce reaches 52,000 employees, composed of professionals, engineers, architects, technicians, clerks and office personnel, who come from different countries in Asia and the Middle East. Many of the management staffs are from the UAE. It is correct to say that constructions awarded to Arabtec Construction Co. are managed and operated by cross-cultural project teams. These are culturally-diverse people with different backgrounds, values, religious beliefs, and ways of life (Arabtec Construction, L.L.C.: about us 2011).

Background

Arabtec started as a construction company during the construction boom in the 1970s in the UAE’s emerging industry. Its first project was the construction of three cold storages in the different parts of the UAE, such as Dubai, Abu Dhabi and Muscat (Arabtec Construction, L.L.C.: company history 2011).

Other completed projects include residential blocks at the UAE University, installation of oil-filled cable in collaboration with a Swiss company named Cablex, construction of private villas, warehouses and large facilities in Dubai and other parts of the UAE. The remarkable and beautiful design of Abu Ghazaleh Building in Sharjah is Arabtec’s pride as a builder. The company survived the depression in the 1980s with a careful handling of its finances and resources.

Other major accomplishments include the high-rise Burj Khalifa, known as the tallest structure in the world, the Emirates Palace Hotel, the Automobile Distribution Centres in Ajman, the Al Futtaim Commercial and Residential Building in Dubai, and many others. It also became involved in the oil and gas construction projects in Abu Dhabi, the GASCO and ADCO. To add more, Arabtec has been involved in large building and residential projects, complexes, and private and public buildings mostly in the UAE and the Middle East (Arabtec Construction, L.L.C.: company history 2011).

Newly awarded projects are large construction projects such as the Midfield Terminal Building, situated at the Abu Dhabi International Airport, the Dubai International Airport expansion project, and another residential development in Abu Dhabi (Arabtec Construction, L.L.C.: projects 2011).

Its workforce is composed of project teams with professional engineers and members coming from the different parts of the UAE, and the world. Many of its highly-skilled construction workers come from the different parts of Asia, particularly the Philippines, India, Pakistan, China, and other Asian countries. Members of the management staff also come from the United States, Britain and Europe (Arabtec Construction, L.L.C.: about us 2011).

Conclusion

This chapter discusses published literature on the research thesis and justifies reasons of my research. This chapter also analyses the various components involved in communication in relation to strategic project management (SPM) including project and project management, culture, training and the organization; Arabtec Construction company. The next two chapters entail the research methodology, sample population, analysis and discussion.

Methodology Review

The purpose of this paper is to determine the strategic role of communication in a cross-cultural project team. After collecting the desired data and information, the researcher formulated a hypothesis, analysed the data and arrived at a conclusion based on the literature, and the quantitative and qualitative research conducted on project team members of a population, the project managers and employees of Arabtec Construction Company, which is based in the United Arab Emirates.

Methods and methodology are two distinct subjects. A method is a technique or procedure in collecting and analysing data (Dumont 2008, p. 29). Methodology includes other aspects of the research design and choice of particular methods, including justification for the research objectives (Powell 2004, p. 59). Surveys are popular for researchers. In fact, most interchange the words survey and research (Fraenkel & Wallen 2006, p. 397).

Another method was to apply validity and reliability on the research to induce a sense on it (Alwin 2007, p. 290). The data collected in the survey was analysed to provide meaning to what is being studied (McNeil and Chapman 2005, p. 9).

We used Arabtec as a case study because of their effective programs in their projects. A case study research provides clear examples and explanation on the subject management in a cross-cultural context. (Eisenhardt 1989, p. 534)

The methodology used in this dissertation is a combination of literature review and quantitative and qualitative analysis by way of questionnaires conducted on a sample (Alwin 2007). We used secondary and primary researches.

Secondary research was sourced from the literature and various studies on project management, teambuilding, and cross-cultural project teams. Primary research consists of questionnaires conducted on a sample population, the managers and employees of Arabtec Construction Company. Emails were sent to the employees, project managers and members of the different project teams in the company.

It has been noted that for a particular project construction, Arabtec forms various project teams to handle the different tasks in the construction. The whole operation however, is managed by an overall project manager.

Project management does not start with the construction – it starts with marketing. This is known as project marketing. Marketing by marketing professionals of Arabtec conducts the negotiation with prospective clients, and when the deal is done, the project is passed on to the project manager.

The various project teams are led by professionals from different cultural background, and the members are also of various nationalities like Emirate, Arab, Pakistani, Indian, American, British, or Asian. The project team members were recruited by the company from many Asian countries. Many of these workers have stayed with the company for years (Arabtec Construction, L.L.C.: company history 2011).

The names and emails of project managers and workers were secured from a database, and from an “insider” in the company, whom this Researcher contacted. The emails sent to them contained letter requests, stating therein that this Researcher would like to ask their opinion and ideas on the subject of communication within a cross-cultural project team and how the members dealt with the problem of cultural differences in the team.

Included in the emails are forms to be filled up and the questionnaires. The prospective participants were asked to complete the forms; the questions in the forms were mostly about the demographic characteristics of the customers. They were also asked to sign their names regarding their consent to be a part of the survey.

The names of the participants were assigned number codes so that their identity remained confidential, and the names and codes were kept in a database with an assigned username and password, in which only this Researcher had access. This process was also explained in the letter-request.

After more than a week, the email recipients responded to our call and with their corresponding answers to the questions in the questionnaires. Out of the 100 emails sent to prospective participants, 61 responded, with a response rate of 81%. But this Researcher again sent emails to those who did not answer our emails and the questionnaires. Another 12 prospective participants added to our number of participants, making the total number to 73 participants. The response rate became 73%. This is an encouraging development of the research.

The 73 participants – eleven were female – represented 14 project teams involved in various projects of Arabtec in the Middle East and North Africa. However, only 11 project teams were involved in existing projects while 3 project teams were on standby waiting for calls or action. All the participants had time to answer the questions; even those who were in the field, doing their projects had time to answer the questionnaires, and to write, giving this Researcher encouraging statements about this research.

Generally, their message is that they wanted to express their thoughts about being members of project teams of Arabtec. They wanted to inspire others working in foreign land, contract workers who are members of project teams, who have to work away from home. Their message is that, working away from home is a challenge but is part of the job given to them by God as members of humankind. Their pay is their reward for their sacrifices (McIntosh 2003, p. 181).

At first, they find it very difficult to be away from home and their families, and they have to adjust to the new place and the new culture. When they become adjusted, they learn to understand others who are in the same situation. Each member becomes a part of a cohesive force for the organisation. The teams are like families, looking for the welfare of others, supporting each one, and understanding the predicament of other nationalities. This makes Arabtec, the organisation, and its many project teams, effective and unique. It is the only construction company operating in the UAE, helping in building the UAE infrastructures, but also helping the economy grow and be one of the leading economies in the Middle East.

The questionnaire consists of twenty questions, in addition to the questions requesting information on their demographic characteristics. Each question was formulated to find facts and to determine how a member communicates with the other members of the team, and how he/she is adjusted to the various cultures of the different nationalities, and the culture within the organisation.

The questionnaire

The questions in the questionnaires are stated hereunder.

- How long have you been with Arabtec?

- What is your nationality?

- What language do you speak?

- What language do you speak in communicating with other team members?

- If not an Emirati, how were you able to adjust to the culture of the Emirates?

- How long did it take to adjust with the culture in the UAE?

- Did you find it easy or difficult to communicate with the rest of the team?

- What are cultural differences present in the team?

- What problems/difficulties did you encounter as a team member?

- How long have you been with your team?

- How long has this team been in existence?

- How do you define teamwork?

- Is teamwork a difficult goal for any projects you have been a part of?

- How have you attained teamwork?

- If you are assigned to other project teams, will you accept the job?

- What cross-cultural training have you undergone as member of this project team?

- What did you learn in the training?

- What communication training did you undergo as a member of this project team?

- Have you been assigned to other branches/subsidiaries of Arabtec?

- Do you have any suggestions for effective communication in a cross-cultural project team such as your present team?

Results

The participants’ responses

This research used key words to represent the participants’ responses to the questions in the questionnaires. The questions are open-ended which require an explanation or the opinion of the participants. The responses may be short or long statements, depending upon the experience and mental state of the participants. However, the responses have been tabulated and are represented with single words or phrases called codes. These codes were tabulated in tables to present how often they are used as answers by the participants (Online QDA: learning qualitative data analysis on the web: how and what to code 2012).

The higher the frequency or the more a code is used as answers by the participants does not mean they are good answers. But it can provide a picture of how the company provides for its members in terms of communication tools, training, and cultural adjustment.

Here are the responses to the questions:

How long have you been with Arabtec?

Most of the responses were “more than a year”. There were those who answered “less than a year”, and others “more than five years”.

What is your nationality?

The answers indicated that there are various nationalities. Of the 181 participants, 50 were Emiratis, and the rest are spread to various nationalities: Indians, Pakistan, Filipinos, Chinese, British, Americans, etc.

What language do you speak?

Again, the answers are varied, according to the nationality of the participants.

What language do you use in communicating with the rest of the project team?

Majority of the participants responded that they use English in communicating with the other nationalities. This is because English is easily understood by everyone in the team. But the participants said that when they are with their own compatriots or when speaking with their countrymen, they speak their language (English, Pakistani, India, Chinese, Filipino, etc.)

How were you able to adjust to the new culture?

There are varied answers. The 73 participants provided different answers. The codes in the tabulation provide a clear view of the participants’ responses.

Some of the answers are stated below:

- The orientation seminar helped in my adjustment period.

- It was difficult at first, but time enabled me to think and adjust to the culture.

- The members of the team were very cooperative.

- The company is a flexible company; they taught us how to be flexible too.

- We give us enough time and resources to think and adjust to the new culture. Resources include training and development.

- The staff members of Arabtec are experienced people who have taught us how to adjust.

- The company is an understanding company, thinking in terms of family, or we seem we are a part of one whole family.

- Training and development is very important. Through seminars, we learned to adjust to the new environment.

- The members of the staff are very professional. They give us all we want to make us at ease.

- The adjustment period is very difficult. But we have to learn and help ourselves, otherwise you go home to your country early without earning enough for your family.

- I couldn’t adjust so easily because I was always thinking of my family. I have to force myself, thinking that what I am doing is for my family, and my children’s future.

- I’m not a hypocrite, until now I’m still adjusting. But it’s not the same as when I was starting with my job. It was really a hard time for me since this is my first time to be away from my family. I cry a lot when I’m alone.

- The adjustment period depends on how strong you are. But I’m a man. When I left my family and my country, I always thought I could handle it. I think I’m doing fine.

How long did it take you to adjust to the new culture?

Some of the answers include: 1 year; more than 1 year; there were others who answered, “more than five years”.

Did you find it “easy” or “difficult” to communicate with the rest of the team? (Please explain your answer, if possible.)

This question asks not just a choice of “easy” or “difficult” but also an opinion, i.e. if the participant finds it easy, he/she has to provide an explanation.

Most of the participants provided the “easy” answer. It was easy to communicate with the other team members because of the English language. Most participants speak and understand the English language. Others explained that it is a requirement for a contract worker to be able to speak and understand the English language. The management people, who are mostly Emirates, also speak English, and the workers, from managers down to the contract workers speak and understand English.

But there were “difficult” answers coming from the Asian workers. The reason/s given was that they had to learn the English language first before being able to communicate effectively, although knowledge of the English language is a requirement for applicants. The fact is that they had basic knowledge of the language, but not “perfect” knowledge; thus effective communication with and between peers had to be studied first. Communication includes understanding the culture of each of the people you interact. The participants include the aspect of culture, such as the manner of clothing, their religious beliefs, business protocols, and they way others regard or respect their section chiefs or project managers.

What are the cultural differences present in the team?

There are many answers to this question, ranging from the manner of clothing, to behavior, business preferences, office protocol, religion, the Muslim and the Christian religious practices, etc.

What problems/difficulties did you encounter as a team member?

Some of the answers are enumerated here:

- Language is still a problem. I can speak English, but sometimes some people talk to us in their own language. Their English is incomprehensible.

- Culture shock is a problem. I find the culture of others so weird. It took me a long time to adjust to the way others behave.

- Some business protocols are strange to me.

- I find it strange that women do not have equal rights with men here.

- Most of those holding managerial jobs are UAE nationals. I find it unfair because sometimes I feel I am more qualified as project managers than our own project manager.

- I don’t find management as a problem, but I find some of the team members do not know how to follow orders. There are those caught violating SOPs, but they are easily pardoned just because they are Emirates.

- My problem is a question of human rights – we, as workers, have the right to assemble or form labor unions. But that is not permitted here.

- There is no system of checks and balances, and where we can air our grievances.

- We just have to follow; we have no right to complain.

How long have you been with the team?

Majority said that they had been with Arabtec for at least six months before being assigned with their present project teams; some said for a year. Fifty participants said that they had been with their project teams for at least one year and more. Twenty-six said they had spent the last five years with their project teams. Others said they were new with the team.

How long has this team been in existence?

Majority said they did not know because the project teams were already there when they applied for a job and subsequently accepted by the company. Three project team leaders said their teams had existed for at least a year. Five project team leaders said that their project teams had existed for at least five years.

How do you define teamwork?

The responses reflect the ideas and opinion but also the cultural background of each of the 181 participants who come from different countries in the Middle East, Africa, Asia, Europe and the United States. Here are a few of their answers:

- Teamwork is when all the members agree on how to perform their project.

- It is when the leader and the members are working as a team.

- Teamwork results when, after discussion, brainstorming, and deliberation of the various suggestions, you come to a single conclusion, and all of you work for it.

- Teamwork is a must for all human undertaking involving a team with many members.

- A multi-culture team working as one, not minding of their cultural background, is a group working with teamwork.

- Teamwork is accomplished if the group communicates effectively; there is no misunderstanding, but if there are disagreements, they are easily settled out.

- A good, talented, and charismatic leader with talented and understanding members can produce results. That is teamwork.

- Teamwork is learned; it is not attained so easily. But there are times that it is attained easily – it is accomplished by dedicated people, people who were nurtured to work for others and to sacrifice so that others may be benefitted.

- Religion plays a key role in teamwork because God taught us to work along with others.

- Man is a social being, that’s why he/she must work with others, and not individually.

- Teamwork is synonymous with sacrifice. You have to learn to forget yourself to accomplish goals.

- Without teamwork, there would have been no successful projects.

- Teamwork is a very confusing word because it all depends on the leader the members. Sometimes a team has a majority membership of one nationality, for example Saudi or Emirati, and if you are of different nationality mixed with the team, you find yourself a stranger to the team.

Is teamwork a difficult goal for any projects you have been a part of?

One hundred eleven participants suggested that teamwork is not difficult. Their responses also reflect the way they answered Q12. Twenty said it is difficult, while the rest said it depends on the leader and the members of the team. Some other remarkable answers are:

- A well-planned project can lead to teamwork.

- Communication and planning of the team are important parts of teamwork.

- Teamwork is difficult only if the members are selfish.

- There are no easy projects, but they can be made easy with teamwork.

How have you attained teamwork?

- In our team, we have to deal with cultural differences first, before we were able to attain teamwork.

- It was a step-by-step process. Communication is vital. You have to talk and understand others; then all of you collectively plan the work to be done. In other words, the leaders and the members have to talk it out and implement a plan of action.

- The system in the organisation is important. In our team, we worked with a systematic framework. I think it was already there before I became a member. The system is about training, orientation, more training, and understanding culture. Members must learn to understand each other’s opinion and ideas.

- We attained teamwork gradually. It became easy when we considered it not just a part of work, but part of being human beings.

- The multi-culture must be ignored.

- The different nationalities must work as one group, like a single country.

- We ignored the system and worked our own.

- We were creative in a sense.

- We put all our talents and skills.

- There was no selfishness on our part.

- We were very flexible in working out the plan.

- The activities were made easy with our full cooperation.

If you are assigned to other project teams, will you accept the job? Please elaborate.

About half of the participants answered that they would accept other assignments within the company, but almost half also said they wanted to stay with their present assignments or project teams. Some of the comments were:

- I like my job but to be assigned with other project teams, I will accept wholeheartedly.

- If it is the same job and nature of work, I will accept it.

- Whether it is a promotion or not, I will accept it.

- I want to stay with my present team.

- I am comfortable with my project team at present.

- It is difficult to adjust, so I want to stay permanently.

- I like my present position, and to be assigned to another team, I will consider it a demotion.

- I can communicate effectively now with my project team. I will find it hard to start anew.

- I will accept it if I will be transferred to another project team, for as long as it is within the company Arabtec.

- I will be glad to be assigned to other countries or branches of the company. It will be another experience.

- I don’t want to go to other places; it is difficult to adjust to other cultures.

- I want to improve a lot; I like to experience different jobs in the construction industry to be versatile.

What cross-cultural training have you undergone as member of this project team?

Most of the participants answered that they have undergone cross-cultural training or inter-cultural training upon being accepted in the company. Other said that they were allowed to undergo orientation seminar being deployed in the different project teams.

What did you learn in the training?

The participants were very cooperative in expressing what they learned from the training. Some of their answers are:

- Studying how others behave and interact with people is part of our training.

- We studied the cultures of our companions in the team – the Emirates, Arabs, Asians, Americans and Europeans.

- Culture and cultural differences is the main subject of our training.

- We studied how others conduct business and the many protocols in organisational life.

- The similarities between Muslims and Christians, and how they can live together, are a part of training.

- Technical and cultural aspects were diffused, or mixed, to become a successful training program.

- We studied the different cultures within the UAE and some other cultures present in our project team.

- How others dress, behave, what they eat, and everything; mostly the cultures of the Emirates, Asians, and Americans.

What communication training did you undergo as a member of this project team?

- The important thing in communication training is language.

- We studied the basics of the Emirate language and the English language.

- Learning English is the most important, but you have to learn it seriously because there are words I find difficult to translate. I’m Chinese and English is not an easy language for me.

Have you been assigned to other branches/subsidiaries of Arabtec?

One hundred participants said that they had been assigned to other branches within the UAE; fifty said they were assigned to projects in the Middle East. Contract workers from Asia, Pakistan, and India said they had been with their projects, and not been assigned to other projects ever since they were accepted at Arabtec.

Do you have any suggestions for effective communication in a cross-cultural project team such as your present team?

There were many suggestions in the questionnaires, but since we have the codes, these suggestions are summarized, for example:

- Training is a must; it includes language, culture, and the technical aspect of the job. Training must be regular and continuous.

- The company must be flexible and must provide everything the workers need, which includes justifiable salary and benefits, vacation, health and safety in the workplace.

- Equality and human rights must be respected. No discrimination.

- Communication and information technology (ICT) must be a part of training.

- Teamwork can be enhanced and encouraged with continuous development in the organisation.

Tables with codes for the participants’ responses:

Table 1. (length of service).

Table 2. (Nationality).

Table 3. (Language).

Table 4. (Language within the team).

Table 5. (Cultural adjustment).

Table 6. (Adjustment period).

Table 7. (Communication with the team).

Table 8. (cultural differences in the team).

Table 9. (problems and difficulties).

(Note: Participants provided more than one answer to the question; thus the answers exceed the number of participants.)

Table 10. (length of service with the team).

Table 11. (period of existence of the team, accdg. to participants).

Table 12. (Define teamwork).

Table 13. (whether teamwork is difficult).

Table 14. (how teamwork is attained).

Table 15. (will you accept other assignments?).

Table 16. (cross-cultural training experience).

Table 17. (lessons learned in training).

Table 18. (communication training experienced).

Table 19. (places of assignment).

Table 20. (suggestions for effective communication).

Discussion

The questions in the questionnaire were focused on communication and cultural adjustment. What the participants emphasised in their responses was their commitment to their teams. These teams are not made for a certain project; they are there as part of the system. It is understood in this part of the discussion that project teams of Arabtec are not teams formed overnight, and then to be disintegrated after doing their jobs. It might be for some teams, but mostly the teams have their own kind of job.

Be that as it may, the organisation is not lax in providing the necessary parameters for effective communication, along with the adjustment period, for the leaders and team members to adapt to the new environment. The participants hail from the different parts of the world; they have their own cultural differences and biases and when they arrive with the company, they must change their way of life. They have to change their own culture and adopt a new culture, which is strange and considered a combination of several cultures. This is in addition to the rules standard operating procedures (SOPs) of the company Arabtec that they have to follow.

The participants were easily adjusted to the language. This is because they knew English, or English is a must to the applicants looking for jobs abroad. The Emiratis, the people of the place, the immigrants, the contract workers, and everyone including tourists in this country, all speak English. S All contract workers of Arabtec speak English. The company transacts business with English as the medium of communication. o it is not a big problem for the members and leaders of team to communicate.

What really hinder others to be effective in the team are several factors. These are embodied in Question No. 9, which is about the problems and difficulties of the workers. The participants gave more than one answer to the question; meaning each has several problems or difficulties as members of the project teams. The coded answers appeared more than once in the tabulation, which is quite understandable.

Let’s take a look at the highest scorer in the answers, and that is culture shock, which gained a score of 75. An investigation into the questionnaires told this Researcher that the answer with the word “culture shock” appeared 75 times, with about one or two other problems accompanying it, mostly “homesickness” or “religious beliefs”

The next problem or difficulty is English language. While it is true that all participants knew the English language, we must take into consideration that many of them have English as the second language. They may be able to communicate but they still have to adjust to the language. They have their own primary language at home. Some of the participants said that they like to be with their own countrymen so that they could speak their native language.

“Religious beliefs” is another difficulty. But this is related to the differences between Muslim and Christian beliefs or traditions. Many of the contract workers were Christians; so they have to adjust with the Muslim religion and tradition. Of course, this might be considered a minor problem for the members, since the Emiratis, who mostly run the project teams, speak English. And they have the majority in most project teams.

Homesickness is a major problem/difficulty for the migrant workers, but that is understandable as all of us feel it, one way or the other. Some commented that they are able to adjust and to counter homesickness by being with friends, and going out for shopping for socialization. Others remain in their quarters, thinking of home and their loved ones. Family problem is related to this. The question of family problem could not be explained and this Researcher could not ask for more explanation; as the term connotes, it is a family affair.

Another puzzle is the question of business protocol, as listed in one of the problems. This Researcher has the understanding that business protocol relates to how management, mostly citizens of the UAE, conducts business. The Muslims have their own way of business relationship, which is a bit different from the Christians.

Literature review analysis