Introduction

With increasing demand for petrol with increasing global prices of oil, it is interesting to study the relationship between pricing elasticity of petrol and market power. It was Alfred Marshall who introduced the concept of elasticity of demand into economic theory. Price and demand are inversely related. In other words, a fall in price leads to an increase in demand. Thus, demand expands or contracts, in response to the pressures exerted by price. The expansion or contraction of demand of petrol in New Zealand is an intriguing subject as New Zealand is a small place with four major retail companies dealing with petrol.

Thesis: Studies show that generally petrol is an inelastic commodity in the short run and its price elasticity of demand can be increased by fuel economy vehicles and through taxes.

Price elasticity of demand refers to the degree to which consumers change their consumption of a product in response to changes in the price of the product. It represents the rate of change in the demand as a consequence of rise/fall in the price of a commodity. The price elasticity of demand can be measured with help of the following formula:

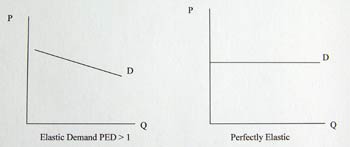

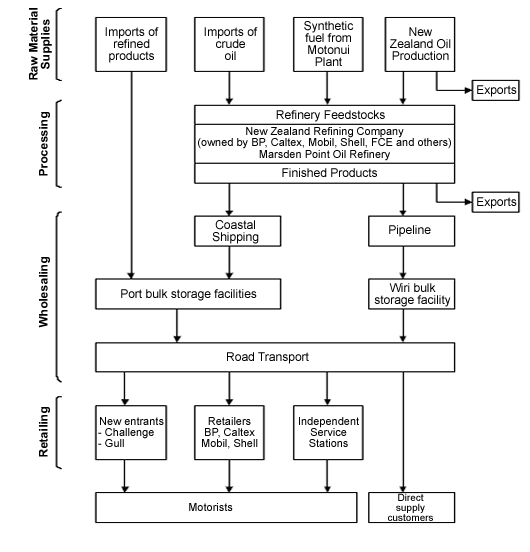

A small fall in price of a product may lead to a considerable increase in the quantity demanded, but sometimes even a considerable fall in price may not lead to any increase in demand. The responsiveness of demand to small changes in price differs from product to product. There are five different relationships possible between a change in price and a change in quantity demanded (Krishnamurthy, 2002):

- Demand with unit elasticity: Where a given proportionate change in price causes an equal proportionate change in the quantity demanded. Ed = 1

- Demand with more than unity: A change in demand is more than change in price. Ed = > 1

- Demand less than unity: This can also be stated as inelastic demand as a decline in price leads to less than proportionate increase in demand. Ed = < 1

- Perfectly elastic demand: In this case, no reduction in price is needed to cause an increase in demand. Ed = 0 or ∞

Goods which are elastic tend to have some or all of the following characteristics: they are luxury goods; they are expensive and a big % of income e.g. sports cars and holidays; goods with many substitutes and a very competitive market; bought frequently (Pettinger, 2008).

- Perfectly inelastic demand: In this, a change in price, however large, causes no change in quantity demanded. Ed = 0

Goods which are inelastic tend to have some or all of the following features: they have few or no close substitutes, e.g. petrol, cigarettes; they are necessities; they are addictive; they cost a small % of income or are bought infrequently (Pettinger, 2008).

In the short term demand for oil is usually more inelastic because it takes time to find alternatives.

Impact of OPEC on price of Oil: Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) is an association of oil-producing nations set up in 1960 with the express purpose of influencing oil prices by controlling supply. The OPEC countries are Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Qatar, Indonesia, Libya, United Arab, Emirates, Algeria, Nigeria, Ecuador and Angola. In 2000, it adopted a price band of between $22 and $28 a barrel, levels a world away from current prices.

If the price went below $22 a barrel, production quotas would be cut. If it went above $28 a barrel, production would be raised. OPEC abandoned the price band in 2005 and now has no official price target (BBC, 2008). When its members meet, they try to co-ordinate future production with their predictions for demand. While there have been increases in production recently, the price of oil has continued to soar. OPEC’s official position is that there is plenty of supply in the market. It says rising prices are the fault of investors in the financial sector, who are buying oil contracts in order to sell them on without ever planning to take delivery.

Clearly there are limits to the amount production can be raised, and OPEC also sees dangers in increasing supply further. There is a fear that the financial sector will decide that there is over-supply in the market and move into other investments if the supply of oil is increased. That problem is exacerbated by the time delays in the system. If producers in the Gulf, for example, decide to increase production, it will be about three months before any extra oil reaches the market (BBC, 2008). If the announcement of extra production caused a big fall in prices, then the extra oil actually hitting the market three months later would exacerbate the problem. And the members of OPEC have a great deal at stake as they depend mostly on oil for their economic health (BBC, 2008).

Petrol and Elasticity of Demand

Generally speaking, demand for petrol is quite inelastic due to many reasons: oil or petrol has very few close substitutes; gasoline is viewed as a “necessity” by most people who are willing to sacrifice other goods and services to spend more on gasoline in the short run; in the short run, consumers do not have much time to alter their buying behavior in response to price spikes by buying fuel efficient vehicles or riding bicycles or walking; and finally, gasoline expenditures are still a relatively small portion of most household budgets (EH, 2008).

Thus, even if there is an increase in the price of petrol, consumption of petrol is not reduced. The estimated Price elasticity of Demand of petrol of -0.1 in the short term. But consumers do react to changes in price of petrol for an individual petrol station and increasing price can lead to a loss of market share of a particular petrol company if there are many petrol companies in the market. An only petrol station in a rural area or a petrol station in the highway has a lot more market power and in these locations, petrol stations have more market power, consumers less choice, demand inelastic; and this is why petrol is more expensive (EH, 2008).

Oligopoly in petrol markets in New Zealand

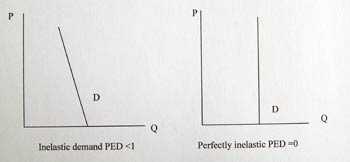

In New Zealand, most of the petrol is supplied by the big four: BP, Caltex, Shell and Mobil. These four companies buy their crude oil stocks on the same global markets, ship it to New Zealand in the same ships, process it in the country’s only oil refinery, which they jointly own, ship it around the country through a shipping company they jointly own, and store it at terminals they share (MED, 2004). Hence they have the same fuel prices Australia’s Competition and Consumer Commission in its report on the petrol industry has pointed out that while the industry was “fundamentally competitive, it became clear in the course of the inquiry that the major refiners have established a comfortable oligopoly” (MED, 2004).

Potential competition among them is limited by “buy-sell” contracts through which the companies agree to supply each other. There is also limited opportunity for independent imports outside the big four partly because of limited access to terminals and wharfage. The dominant characteristic of an oligopoly market is that there are only a few producers and sellers of products and the industries are typically on a large scale. Oligopolists are more concerned with competition from inside the industry than from outside.

There is competitive pricing between the rivals. Shell in New Zealand cannot afford to cut prices as it will lose its customers and if it cuts its prices there would be a price war with competitors falling suit (Stewart and Moodie, 2004). Therefore, oligopoly participants come to an agreement regarding pricing and there are three ways of doing it: gentlemen’s agreements, price leadership or formal arrangements (Steward and Moodie, 2004).

While petrol prices have been pushed up by high global refining margins, New Zealand refining fees are capped under a deal between NZ Refining and the big four. This means motorists, with daily oil price changes, motorists are immediately paying for higher refining margins, but BP, Caltex, Shell and Mobil are not. The benefit of this deal to the big four is currently $US12.4m ($16.1m). In Australia, there is a delinking between world market prices and retail prices and pump prices vary in a weekly cycle, cheapest on Tuesdays and most expensive on Thursdays.

Market monitoring company Informed Sources sees this “Edgeworth cycle” as a sign of an absolutely pure competitive market. According to Alan Chad New Zealand’s lack of an Edgeworth cycle indicates a less advanced and less competitive environment than Australia. “In order to get to that Edgeworth cycle you need to have free access of minor players to product,” he told the Star-Times. Only a more competitive market can restrict its New Zealand petrol price monitoring to “drive-by” services. In conclusion, New Zealand’s market is not competitive at wholesale level. So although there is retail competition, it makes limited difference to prices.

Price Elasticity of Demand of Petrol

Estimates of the short-run price elasticity of gasoline demand for the period from 1975 to 1980 range from -0.21 and -0.34 and are consistent with estimates from the literature that use comparable data. However, estimates of the price elasticity for the more recent period are significantly more inelastic ranging from -0.034 to -0.077: the short-run price elasticity of U.S. gasoline demand is significantly more inelastic today than in previous decades (Hughes et al, 2008).

This result has important policy implications. The short-run price elasticity is a measure of the change in driving behavior as a result of a change in the price of gasoline. A driver’s response to higher prices is largely composed of a reduction in the amount of driving (vehicle miles traveled) and an increase in the fuel efficiency of driving. Hughes et al (2008) present the results of their study suggesting, that on average, U.S. drivers appear less responsive in adjusting to gasoline price increases than in previous decades.

It may be the case that today’s U.S. consumers are more dependent on automobiles for daily transportation than during the 1970s and 1980s and as a result, are less able to reduce vehicle miles traveled in response to higher prices. Another hypothesis is that as incomes have grown, the budget share represented by gasoline consumption has decreased making consumers less sensitive to price increases. The price income interaction model shows that gasoline consumption is more sensitive to price changes as income rises. The hypothesis proposed by Kayser is that as incomes rise, a greater proportion of automobile trips are discretionary.

Alternatively, at lower income levels, the amount of travel has already been reduced to the minimum leaving little room for adjustment to higher prices. Another possible explanation is that the number of vehicles per household increases with income. There is also the possibility that drivers are using more fuel efficient vehicles as gasoline prices rise. Whatever the explanation, the overall decrease in price elasticity despite growth in incomes suggests that today’s consumers have not significantly altered their gasoline consumption in response to higher gasoline prices. It is important to note that these results measure consumers’ reactions to short-run changes in gasoline prices.

However, it is the long-run response that is the most important in determining which polices are most appropriate for reducing gasoline consumption. As it turns out, it is relatively difficult to measure long-run gasoline elasticity in practice due to factors such as the cyclical nature of gasoline prices (Hughes et al, 2008). Analysis of the short-run price elasticity does however provide some insight into long-run behavior.

The long-run response to gasoline price increases is the sum of short-run changes (miles driven) and long-run changes (fuel economy of the vehicle fleet). The short-run results suggest that consumers today are less responsive in adjusting miles driven to increases in gasoline price. This component seems unlikely to change significantly for long-run behavior. The highly inelastic values that are observed suggest that the vehicle fuel economy component is also small.

If the long-run price elasticity is in fact more inelastic than in previous decades, smaller reductions in gasoline consumption will occur for any given gasoline tax level. These results suggest that technologies and policies for improving vehicle fuel economy may be increasingly important in reducing U.S. gasoline consumption.

New Zealand and Price Elasticity of Demand for Petrol

In her conference paper titled “Fuel Price and Fuel Consumption in New Zealand” (2002) Sandra A. Barns provides the following statistics:

Evaluation of Elasticities for New Zealand

Table 1: Price elasticity estimates.

Sandra A. Barns points out that the low price elasticity demand for petrol is expected because substitutes for petrol are relatively few. The price elasticity for petrol has a larger impact in the short-run at -0.195 (significant at 1 percent), compared with -0.065 (significant at 10 percent) in the long run. The magnitudes indicate that initially when prices rise, commuters take advantage of available substitutes (although substitutes are limited in the short run, reflected in the price elasticity of demand), but over a longer period, their behavior tends to return to pre-price-change patterns. This pattern was similar to that found in the United States.

Khazoom (1991) explained this pattern by arguing that initially a price rise reduces short-run demand, but in the long run consumers switch to vehicles that are more efficient which lowers the marginal cost of travel, and in so doing encourages a greater demand for travel. The magnitude of the short-run price elasticity found in the case of New Zealand is similar to that found in other research, while the magnitude of the long-run elasticity is lower than in all other studies reviewed (Barns, 2008). This suggests that New Zealanders’ short run response to petrol price increases is similar to citizens of other countries, but the long run is lower.

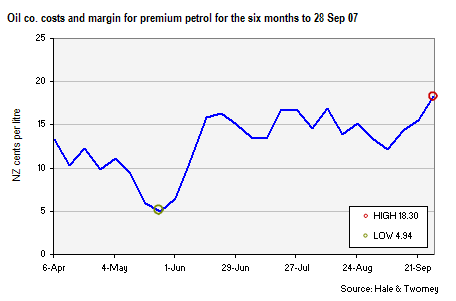

This is a reasonable finding as growth in transport in New Zealand exceeded the growth in economic activity for the 1990 to 1998 period (Barns, 2008). While strong demand is continuing to increase fuel oil prices, the improving New Zealand exchange rate has resulted in a lower landed cost (FuelPriceMonitor, 2007). More recently, strong demand for oil is continuing to increase fuel prices as can be seen in the graph.

Oil prices are on the rise to the point of alarming all countries in the world. On the basis of price elasticity of demand concept, there should be a fall in oil demand due to high prices. Fall in demand will or should mostly concern the ultimate consumers like industrialists and manufacturers, who depend on energy-intensive and oil-intensive raw materials, and also use process energy, to produce goods. Intermediate users, tend to ‘pass on’ the energy price rises they suffer by increasing their final prices more than strictly justified by their raised energy costs. This further penalizes final users, causing faster or further economic downturn.

The price elasticity of demand for petrol is largely dependent on the availability of substitutes. Short run substitutes include the curtailment of travel, public transport and carpooling, improved vehicle maintenance, and reduced driving intensity. Where households have more than one vehicle, increasing the relative use of newer vehicles (which tend to be more fuel efficient and less polluting) is also a short run substitute. Long run substitutes include the purchase of newer vehicles, and changes in proximity of residence and workplace (Khazzoom, 1991).

Microeconomic theory posits that long run price elasticity of demand should be greater than short run because the available substitutes in the long run include all short run options, plus those that are only available in the long run. The almost total absence of real, efficient, convenient or cheap alternatives to oil and gas explains why everyone is dependent on them. Oil demand in New Zealand and around the world is growing at a rate of 5% per year and is directly increased by higher oil and gas prices.

Price elasticity of demand is unable to explain what is happening. The bottom line is however very simple: until and unless interest rates are sharply raised, to double-digit annual rates, oil and gas prices can go on crawling ever up in New Zealand.

Conclusion

Generally, when a commodity becomes scarce the price goes up. This causes people to use less of the commodity and begin look for alternatives for it. Unfortunately, energy is not just any commodity. As it is the very basis for all economic activity, including the generation of alternative sources of energy, it is nowhere near as “elastic” as most commodities. Economist Andrew McKillop explains that since early 1999, oil prices have risen about 350%. Oil demand growth in 2004 at nearly 4% was the highest in 25 years. These facts conflict with existing notions about “price elasticity”. McKillop says: “World oil demand, tends to be bolstered by “high” oil and gas prices until and unless “extreme” prices are attained” (McKillop, 2004).

During the oil shocks of the 1970s, oil prices shot up by nearly 400% (Lima, 1998). But demand did not fall until the world was mired in the most severe economic slowdown since the Great Depression. The only relief was provided by the discovery of new oil fields in the North Sea and Alaska and increased production in countries such as Venezuela and Saudi Arabia (Lima, 1998). In the present day context, in New Zealand, with world oil production almost peaking, increase in production is not easily possible. Hence the emphasis should be more on fuel economy and increasing interest rates.

Bibliography:

Barns, A. Sandra (2008). Fuel Price and Fuel Consumption in New Zealand: Would a Fuel Tax Reduce Consumption? Web.

BBC (2008). OPEC: The Oil Cartel in Profile. BBC News. Web.

EH (Economics Help) (2008). Elasticity in the Petrol. Web.

Hughes, E. Jonathan; Knittel, R. Christopher and Sperling, Daniel. Evidence of a Shift in the Short-Run Price Elasticity of Gasoline Demand. Web.

Khazzoom, J.D. (1988). Conservation versus environmental policy: Unintended consequences. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 7, (4), 710-713.

Krishnamurthy, G. (2002). Managerial Economics. Annamalai University Publication. Chidambaram, India.

Lima, Paul (1998). Peak Oil Puts Africa in Play Again. Web.

McDermott, John and Bagrie, Cameron (2005). NZ economy might slip on oil prices. ANZ. Web.

McKillop, Andrew (2004). Oil Demand – Why So Strong? Web.

MED (Ministry of Economic Development) (2004). Effects on the Transport Fuels Industry. New Zealand Institute of Economic Research. Web.

New Zealand Fuel Price Monitor (2007). Hale and Twomey Market update. Web.

Pettinger, R. Tejvan (2008). Price Elasticity of Demand. Web.

Stewart, James and Moodie, Beverley (2004). Economic Concepts and Applications. Third Edition. Pearson Education. New Zealand.