The history of Mental illness

Mental illness can be described as a state of emotional stress, which maybe in the mind or the heart. Mental illness is mainly the disorder of the brain that interrupts with a person’s thinking and the ability to relate to others.

In most cases, mentally disabled people have been referred to as lunatics; this was because in the earlier years, people “believed that insanity was caused by a full moon at the time of a baby’s birth or a baby sleeping under the light of a full moon” (Leupo, n.d).

Mostly, the lunatics were shunned from the society since they were believed to be possessed by evil spirits. Nevertheless, in the colonial times, the colonialists implemented medical measures that were believed to cure the insane; they included submerging the victims in ice-cold water until he regains consciousness, or the execution of a shock into the victim’s brain.

Another method involved draining of bad blood from the individual. However, all these inhuman practices resulted to deaths of the patients. In the 19th century, moral management was introduced as a treatment method for the mentally ill. This method involved the replacement of chains with beds and decorations. It was believed that creating a suitable atmosphere for the patients would give them comfort and yield to fast recovery.

After the civil war in America, cases of mental illness increased due to pots war trauma, hence the state provided money for further establishment of mental asylums. In 1930s, Walter Freeman invented an improved medical procedure that could be performed fast and the patient required minimum care after the procedure, which was known as the trans-orbital lobotomy.

This method involved inducing sedation on the head of the patient, rolling back one of the patient’s eyelids, and “inserting a device, 2/3 the size of a pencil, through the upper eyelid into the patients’ head” (Leupo, n.d). A device was then tapped with a hammer through the patient’s head until the desired depth was achieved and finally, the device was pushed back and forth within the patient’s head.

Due to the many medical practices that were performed, the mental illnesses declined drastically by 1986 in the United States (Leupo, n.d). According to Bewley (2008, pp1), the introduction of evangelism played a huge role in introducing humane in the cases of lunacy which was referred to as a psychological approach that was based of a moral approach, thus guiding the insane victims to recovery. Nevertheless, cases of mental illness continue to revolve around us and are present even in the 21st century.

The social welfare policy

Social welfare entails the actions taken by the government or institutions to provide standards and opportunities to people facing contingencies. It is inclusive of social services provided by the country for the benefit of its citizens. In the United States, charitable organizations normally volunteer to address special cases like the mentally ill.

According to Thomas (1998), in 1960, the mental health reforms initiatives were passed and these reforms were aimed at changing the inhumane nature of mental hospitals that existed. The then joint commission on mental illness released an action for mental health, with the assistance from medical centers.

There were a number of mental health centers in 1963, but due to the financial crisis after the Vietnam War, they were not well funded. In return, patients were released to an environment that lacked mental health care. This was unethical since the patients were being released to the society when not fully recovered, and that was seen as a threat to the society.

However, when President Carter took over the office, he later appointed a commission to look into mental health and the commission was supposed to survey and make recommendations on the changes that had to be done on the mental health services.

During the survey, the commission noticed that the families of the mentally ill patients were affected by the fact that these patients received minimal care. Indeed, the mentally ill situations changed, hence taking away their families’ worries (Thomas, 1998).

Social aspects on mental illness involve a psychiatric help, whereby in the developed countries it involves treatment, counseling of the patient’s family. However in the United States there are legal standards that require the mentally ill to seek treatment.

The idea of a social welfare system is viewed as a collective responsibility designed to provide and support organizations that are working to provide specific resources to those who cannot afford them financially; they include, Medicare, unemployment, and mental illness among others.

Laws governing mental health in the United States

In the United States, laws based on mental health vary among states; however, these laws are categorized into three categories including “equal coverage laws, minimum mandated mental health benefit laws and mandated mental health ‘offering’ laws” (States laws mandating of regulating mental illness 2011).

Equal coverage laws (parity laws) prohibit insurers or health care practitioners against discrimination mental illness or any other kind of illness. In addition, insurers are required to provide the same benefits to mental illness as other illnesses; “these benefits include deductibles, co-payments, lifetime, and annual limits” (States laws mandating of regulating mental illness 2011).

In minimum mandated mental health benefit laws, it is the role of the government to ensure that there is some coverage on “mental illness, serious mental illness, substance abuse or a combination thereof” (States laws mandating of regulating mental illness, 2011).

Mandated mental health ‘offering’ laws usually “do not require that any benefits should be offered at all”; hence, such laws seem to create an opportunity for making a choice on whether to provide specific cover for mental illness to the already insured clients (States laws mandating of regulating mental illness 2011).

According to the public law on mental benefits sec 712, “if the plan of coverage does not include an aggregate lifetime limit on all medical and surgical benefits, the coverage may not impose any aggregate lifetime limit on mental health benefits,” hence prohibiting the health plan from imposing restrictive lifetimes on the spending for mental illness compared to physical illness.

Philosophical attitudes and perspectives concerning mental illness

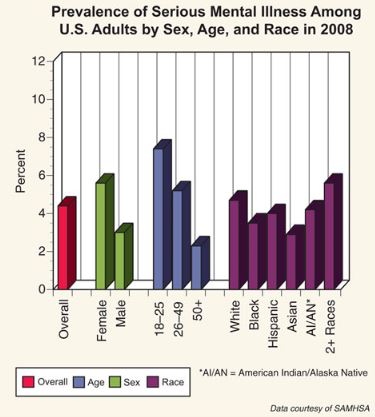

In the United States, mental illness can be rated in one out of four adults and 30% of Americans suffer from mental disorder (National institute of mental health 2010). In the United States criminal justice system, an insanity plea is used in less than a percent of criminal case.

In cases where the guilty are acquitted, it is solely based on convincing evidence that one was not in the right state of mind when performing the act. Stigmatization and marginalization still exists for the mentally ill; this is because they are mostly considered violent and the society does not want them around ordinary citizens because they are seen as a threat to security at times.

However, according to the BBC news (2001), the mentally ill are six times likely to be murdered but also the rate of suicidal for the mentally ill is very high, hence the need for attention of the deaths of the mentally ill is an urgent concern.

In addition, according to a research conducted in 1993, 73% of deaths were caused by suicides by the mentally ill, hence concluding that the mentally ill patients had a six time possibility of been murdered compared to ordinary people.

However, in the world we live in, being mentally ill can result to arrests as the insane people are mistaken for criminals. Most mental institutions were associated with neglect and abuse, however, in the 21st century, more mental health services are available and affordable.

Moreover, there are federal laws protecting the mental patients. Being mentally ill is associated with self-harm; hence, the need for health services is important. Nevertheless, due to fear of the society, the mentally ill patients are shunned away and are unwanted.

Criminal victimization is common among the mentally ill patients, whether in the society or in prison, according to Hiday et al (1999), resulting to a research on crimes conducted by the mentally ill patient who were involuntary admitted as psychiatric patients by the court.

The results indicate that sexual abuse and neglect can cause mental disorders even if these events occurred in childhood. Nevertheless, victimization occurs on the streets and neighborhood where these patients hail from. Mostly, they are victimized due to their mental state and their conditions of living.

The author adds that, due to the isolation and lack of work, they easily engage in drugs, hence engaging in violence. The most affected are women who suffer from mental illness, since they are prone to rape and assaults if not in a supervised environment.

The author insists on the provision of safe environment for those with severe and persistence mental illnesses, an environment that will make them feel safe and secure such that they can benefit medically.

Human service workers mainly make a difference in people’ lives; their aim is to meet the human needs by providing quality services. The community based human service workers move around a community catering for the needs of the community.

These workers vary in their professions, including, childcare workers, counselors, and mental health practitioner among others. These workers work tirelessly to make a difference in the patient’s lives. For the mentally ill who are homeless, they determine where they should be located to receive rehabilitation. According to Speier (pp 6), in human service philosophy, the mentally ill are treated as people first and their needs are equivalent to the needs of ordinary human beings.

They view the mentally ill as people with feeling, since in times of disasters, they are the hardly hit by the effects and they are emotionally affected too. Speier further adds that the mentally ill patients are highly affected by the change of environment and have difficulty in adjusting to those circumstances, therefore making the mentally ill equal to the rest of the population.

On a personal note, having had an encounter with a mentally ill person, who approached me, asked me to buy him a meal, and even insisted he did not want even a dollar – all he wanted was something to fill his stomach.

After buying him the meal and handing over to him, I noticed a sparkle on his face a sign of happiness and satisfaction that remains vivid in my mind. Surprisingly, this mentally ill person never forgot my face and anytime we crossed each other’s paths, he would thank me over and over again.

From that experience, it is evident that these isolated people just need care, attention, and love. When they feel wanted, they will not have the urge to run away to the street. Instead, they always keep a fresh image of those who treat them well and the friendly environment in which they feel safe and secure, such that, they do not desire another world. It is however, the responsibility of the society and their families to create a friendly environment for them and ensure that they receive medical attention incase of the severe mental cases.

Conclusion

Depression is the main contribution to mental illness; moreover, it is a major cause of suicidal thoughts and even suicide. Therefore, except for the generic case of mental health that is hereditary, the other cause of mental illness should be avoidable.

Promoting of a good health is necessary for the mental health as well, just as we prevent our bodies from acquiring diseases such as malaria. The same applies to our mental health, hence avoiding stress that could result to depression and yield to a mental disorder.

It is important to free our minds from stress and anxiety, eats well, and has a good night sleep. With this in mind, depression, which is a cause of premature death, can be avoided. Nevertheless, the mental illness patients should not be neglected and victimized; they should be accommodated or referred to mental institutions where they can receive sufficient help. The society is to blame for shunning away the mentally ill and for treating them less human, it is our actions that contribute to the fate of these patient, who end up engaging in violence and theft as a means of survival.

References

BBC News. (2001). Murder risk ‘higher for mentally ill’. BBC News. Web.

Bewey, T. (2008). Madness to mental illness: a history of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. NY: RCPsych Publications.

Hiday, A. M. et al. (1999). Criminal Victimization of Persons with Severe Mental Illness. Web.

Leupo, K. The history of mental illness.Web.

National institute of mental health (NIMH). (2010). Web.

Speier, T. Responding to the needs of people with serious and persistent mental illness in times of major disaster. US department of health and human services. Web.

States laws mandating of regulating mental illness. (2011). National conference of state legislatures. Web.

Thomas, A. (1998). Ronald Reagan, and the Commitment of the Mentally Ill: Capital, Interest Groups, and the Eclipse of Social Policy. Electronic Journal of Sociology. Web.