Introduction

In Hinduism, there are three major deity figures which are Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva. They are often viewed in the Indian temples and presented with offerings, in the vital form of worship referred to as “Darshan”. It requires the worshipper to make eye contact with the deity in order to receive blessings.

Today we are looking at the Shiva Nataraja, which is one of three major deities in Hinduism. This paper looks at the relevance of the image of Shiva to the Hindu culture, and the disparity between its presence in a temple and display in a museum of art, away from the culture that identifies with it.

Description

The sculpture of Shiva Nataraja is displayed at Denver Art Museum. Like other Indian figures, Shiva has a slender frame that is characterized by precision of posture, and sharpness, as well as, its relation to dance. Shiva, The King of Dancers, is dancing at the center of a circle of fire that represents the universe surrounded by gods.

The dance is referred to as “Anandatandwa, and it represents the cosmic cycles “such as the daily rhythm of life, which entails birth and death”. The god has his left leg raised across his body, and his right leg firmly on the ground, but bent at the knee.

“Shiva is also holding a flame in his left upper arm, a drum in his right upper arm, and gesticulating with the lower arms”. The dwarf at the foot appears to be staring at Shiva, who is heavily decorated with jewelry on his neck, wrists, and ankles. The image of Shiva also has a hole at the bottom to make it easier to carry as shown in figure 2. The image of Shiva, as observed in the museum, is shown in figure 1 at the end of the paper.

Background

The bronze sculpture of Shiva, the demon god, was first presented to his worshippers in the period between the ninth and thirteenth centuries. During this time, the Chola ruled over Tamilnadu and other parts of southern India. The Chola kings and queens fostered schools for the design and construction of exceptional bronze sculptures to serve as Hindu gods and goddesses known to them as “utsavamurtis”.

Initially, the deities could only be viewed by the noble people such as monarchs and priests, but they were later presented to the population for worship. The design of the sculpture was precise, with the sculptors taking their time to bring out all the details including the “peak of the flames, the face of the dwarf at the right foot of the Shiva, and the elements defined by each hand”.

Elements of the image

According to the museum label, this statue of Shiva Nataraja is from the Chola dynasty. Considering the long process involved in the creation of bronze idols, the Shiva Nataraja is exceptionally beautiful. Its construction was similar to that of making the bronze Buddha. The process is called lost wax casting. It involves the construction of the first sculpture from clay, which is then dried before heating it in a kiln to remove the wax.

After they are certain that all the wax has melted, the clay sculpture is dipped in hot melted bronze. After it has dried, the clay is removed and the bronze sculpture polished. Once the image is ready, a ceremony is performed. This involves carrying the statue onto the street for people to perform a “Darshan”.

Alternatively, the statue can be displayed in the temple for worshippers to present their offerings in the form flowers or covering it with a white scarf.

Even though the image of Shiva is in a museum instead of a temple, people still take their time to visit the Denver Art Museum to view the image. Viewers sit in front of the image and spend hours staring at the four armed bronze Shiva dancing as they meditate.

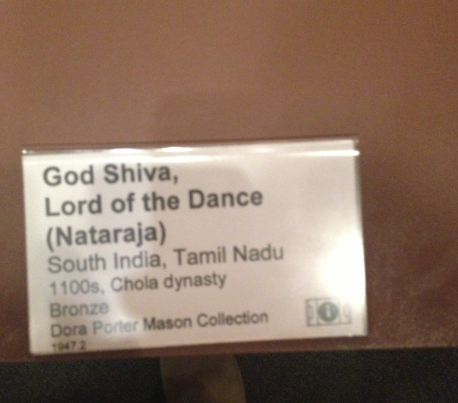

Other people just enjoy the beauty of native art. Viewers are provided with various information about the image including its name as “God Shiva, Lord of the Dance (Nataraja), its place of origin, (South India, Tamil Nadu), the era in which it was first developed (1100, Chola dynasty), the material used for its construction (bronze), and the gallery in which it is part of (Dora Porter Mason Collection donated in 1947).

On the image, a Shiva is proposing a dance position in a fire circle. He has multiple hands sticking out from his body and we can clearly see that some of them are holding objects. And Shiva is standing on a baby looking figure, which is the demon-the bad guy. He has a mermaid looking figure in his hair, which decided as the reference of “Gengi River”.

This information is presented in figure 3 shown at the end of this paper. The image of Shiva, King of dancers is just under 37 inches high. It was donated to the Denver Art museum by the Dora Porter Mason Collection in 1947 and received by the then director, Dr. Otto Karl Bach. Dr, Bach had an astute appreciation for Asian art, and remained director for thirty years in the period between 1944 and 1974.

Impact of the image

The idol of Shiva Nataraja, which was originally found in South India, is currently placed on the fifth floor of the Denver Art Museum. It is the largest image of Shiva that is available on display, which provides its viewers with insight and awe as it portrays the culture of Hinduism.

The sculpture has a rich symbolism that portrays the religious elements of south India that serves to “remind the dutiful Hindu that life is a spiritual process that is eternally subject to change”. The image has the ability to draw a viewer with its multiple arms that seem to be entangled in its body, in addition to the beating drum, which creates the impression of a rhythmic sound signifying change and imbalance of the material world.

The image of Shiva is displayed in the Denver art Museum as part of the Asian art collection along with other images from China, India, Japan, and other parts of south Asia. Most of the art collection was donated by the countries where the art was most valued as a representation of Asian artists and artisans.

The images are open for viewing on any day of the week, except Sunday. The placement of the sculpture in a Naudi, as shown in figure 4, was aimed at providing viewers with the impression that the statues are in the temple. However, this effect is not achieved since the image of a god is more valuable in a temple where Hindus can make their offerings; something that cannot be achieved in a museum.

By displaying the statue in a museum, art enthusiasts can appreciate the art of various cultures especially the numerous forms of worship that are practiced in Asia. It will also help to expose the Indian culture for scholars to study it.

But without the environment, this sculpture lost the meaning to being a bronzed Buddha because they never created mean to be in the museum. They meant to be meditated in the temple, or offered and “Darshan” on the street in order to achieve the practice and devotion of the Shiva.

Conclusion

The sculpture of Shiva has a vital religious purpose in Hinduism. The mannerisms of Shiva portray him as rejecting darkness and ignorance in his dance, which Hindus believe to resemble the spray of the sacred River Ganges. Such implications of the image can only be observed if the image remains with the people in a temple, where the worshippers can relate to it at a spiritual level.

This effect cannot be obtained from the image of Shiva in the museum. The Museum has provided an appealing environment (Nauda) for the deity, where it is placed on orange stone, with light coming from the front such that it produces an equally entangled shadow on its background. However, the effect of the sculpture in the museum is not as significant as when it is in a temple.

The museum has made an effort to preserve its original purpose though it would be better placed with worshippers in a temple, rather than scholars in a museum.

Locking the idol of Shiva in a museum prevents worshipers from presenting their offerings, which are made in front of the deity statues. Keeping the statue in the museum has resulted in the loss of its original meaning, which comprised a street festival, “Darshan”, and offerings.

Images taken from the museum

Bibliography

Anonymous. “Lord of the dance.” Humanities – ProQuest Central, 2002: 23(6), 52 – 53.

Dalal, Roshen. The Essentials of Hinduism. New York: India Abroad Press, 2010.

Denver Art Museum. Asian Art. 2012. Web.

Maxwell, Robyn. “Shiva as Lord of the Dance [Nataraja].” Artonview, 2008: 54, 42-43.