Introduction

Many cities around the world compete among each other to host large-scale sporting events. Consequently, they spend many resources in not only bidding but also hosting them (Tasci, Hahm & Breiter-Terry 2018). Some researchers have attributed the desire to host large-scale sporting events to place marketing, urban regeneration and the widespread media attention that organisers get by being event planners (Müller & Gaffney 2018; Müller & Pickles 2015; Theodoraki 2007; Giulianotti et al. 2015). Other researchers have noted that the potential for creating employment opportunities, developing sports infrastructure and strengthening global cooperation explain why event planners deem it worthwhile to spend millions of dollars planning major tournaments (Brown 2015; Tasci, Hahm & Breiter-Terry 2018; Allen 2002).

Hosting mega events is subject to lobbying (Hartman & Zandberg 2015). Powerful international sports organisations, such as the Federation of International Football Association (FIFA) and the National Football League (NFL), often determine the winners of such competitive processes and the organisational quality of events management that should be followed (Hartman & Zandberg 2015). The success of large-scale sports events depends on several factors that influence event planning (Allen et al. 2010; Zhu & Wang 2019). Consequently, it is vital to analyse the impact of these events and evaluate their contributions towards the advancement of their social, political and economic goals (Yeoman et al. 2004).

This report synthesises existing theoretical underpinnings of event management to inform procedures for planning large-scale sporting events. Linked to this analysis will be a review of the potential impact of events management from economic, social, political and environmental perspectives. The need for risk and contract management will also be mentioned in this analysis from sponsorship agreement and program planning perspectives and the findings used to identify evaluation procedures for event management. However, before delving into these areas of analyses, it is vital to understand the key features of major sporting events.

Key Features of Large-scale Sporting Events

The prominence of major sporting events has improved because of the increased profile of international sporting agencies, such as the NFL (Harris 2014). The rising entertainment value of sports and the interest of media partners in such events affirm this trend because millions of people around the world tune in to watch such games. Consequently, the large-scale sports events sector has become lucrative, as seen from the multimillion dollar investments made to organise sports events, such as the Dakar rally, Olympic Games and Formula One (just to mention a few) (Giulianotti et al. 2015).

The immense commercial potential of the sector reflects the love people have for social games. Indeed, large-scale sporting events attract many stakeholders who have different interests. The main interest groups include the government, sports lovers, media and sponsors (Pye, Toohey & Cuskelly 2015; Cummins & Gong 2017). These stakeholders have varied interests in event planning. For example, sponsors are often concerned with advancing their brand images, while international sports associations strive to promote their respective games (Gillooly, Crowther & Medway 2017; Nufer 2016). Comparatively, government agencies aim to maintain law and order, while fans want to be entertained. Therefore, these different groups of stakeholders have unique interests that affect event planning. Nonetheless, meeting their interests could be a difficult task that requires many resources. The section below highlights the resource requirements for organising major sporting events.

The number of people who attend events is also a key feature of mega-sports events because there is potential for signing lucrative sponsorship agreements (Giulianotti et al. 2015). This index is useful in both absolute and relative terms because it highlights the expected number of people who should participate in an event. In addition, information relating to the estimated number of spectators who have tuned in to watch a game and the actual number of people who viewed it will be known (Parent & Chappelet 2017). Relative to this view, poor strategic choices would attract low levels of engagement among community members, while effective strategies would yield high levels of commitment (Tyson, Jordan & Truly 2016; Theodoraki 2007). The methods and techniques used in this assessment often stem from contemporary corporate management tools, such as the SWOT and PESTLE analyses. These tools are beneficial in investigating the internal and external impacts of a mega sporting event and instrumental in not only understanding the current strategic management environment but also the potential impact or opportunities that exist in the field (Frawley 2016). For example, the SWOT analysis has this evaluative rigour.

Resource Requirements and Work Breakdown Structures

Financial capital is perhaps the most common type of input used to plan mega sports events because most aspects of planning require money. Planning such events also come with tremendous infrastructure investments because large numbers of people increase, road, rail and air traffic (de Boer, Koning & Mierau 2019). Therefore, from an organisational point of view, host cities are supposed to have a sophisticated infrastructure network that facilitates travel. In this regard, the selection process for the venue is often an important decision to make during bidding.

Organising large-scale sporting events also requires a robust security arrangement for crowd control. For example, volunteers are supposed assist injured people to access medical care, while law enforcement officers should control unruly fans and maintain order (Ostrowsky 2018). In addition, there needs to be enough fire and medical emergency services at the event to serve the fans (Tjønndal 2018). The section below outlines the steps that will be taken in accessing data and the work breakdown structure for a proposed event, subject to the insights outlined above.

External Factors Affecting the Sector

As highlighted in this document, several external factors affect the planning of major sporting events. For purposes of this review, external factors will be evaluated using the PESTLE analysis. This tool suggests that the macro environment of an event should be analysed by reviewing the political, social, environmental, economic and technological forces affecting it. Relative to mega sporting events, these elements of analysis are discussed below.

Political

The process of planning for a major sporting event requires sufficient political support because of the huge impact games have on communities (Zimbalist 2016). Particularly, the bidding of sports events around the world largely depends on government support (Gift & Miner 2017). For example, Sweden’s bid to host the Winter 2026 Olympic games has been backed by government support to the tune of $5.2 billion (Weiner 2018). The May government in the UK has also supported the UK’s bid to host the 2030 world cup by allocating millions of pounds for the same purpose. The UK government has also set aside £500,000 for Paralympic teams to recruit more players to take part in the 2026 Olympic Games (Ingle 2018).

The process of organising mega sports events also comes with widespread disruptions to the lives of local communities. Relative to this observation, a report authored by Aslan (2017) shows that homeless communities are often affected by such events because authorities force them to vacate cities when games are ongoing. This action prevents them from gaining access to selected social amenities. For example, they may not be able to use the internet, which is a tool for booking sleeping quarters. Such was the case of Minneapolis youth who were evicted from the host city by authorities who were maintaining law and order during a national football championship (Aslan 2017). This problem has also been reported in past events held in Detroit and Jacksonville (Dimattei 2019).

Economic

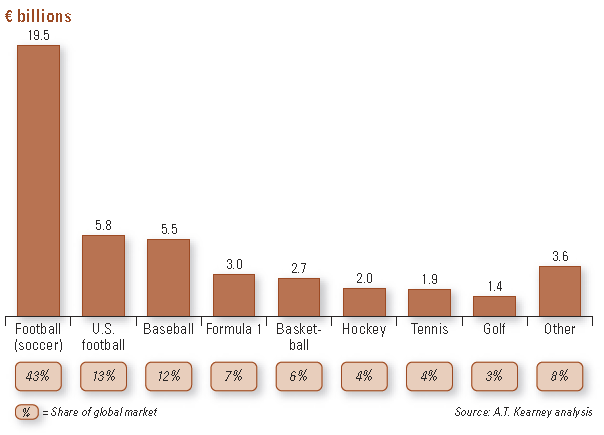

As highlighted in this document, the sports industry is a lucrative sector. Estimates show that the industry is worth in excess of $620 billion, in terms of media rights, sponsorships, food and memorabilia (Collignon, Sultan & Santander 2017). The soccer industry is perhaps the most lucrative segment of the global sports events industry because it accounts for about $29 billion annually (Collignon, Sultan & Santander 2017). Comparatively, the combined value of major US sports, golf events, tennis and Formula 1 is $32 billion (Collignon, Sultan & Santander 2017). Therefore, these statistics suggest that the sector is a profitable one. Figure 1 below summarizes the characteristics of the worldwide sports events market.

Economic considerations are always a priority for many event planners (Abson 2017). Nonetheless, to meet these needs, corporations have to sponsor them (de Boer, Koning & Mierau 2019). In exchange for their support, they gain an opportunity to increase their brand visibility from the widespread publicity and attention that an event attracts. Therefore, sponsorship cooperation and leveraging are important tenets of the event planning process (McDonnell & Moir 2014).

The economic considerations of planning a large-scale sporting event may also influence its content development process. For example, the NBA’s half-time show is one of the most important parts of the game because of its entertainment value. In this segment of the event program, sponsors develop advertisements that would run in this segment of the event and revenues are generated as a result. Based on these insights, maximising the economic value of a large-scale sporting event is a top priority for event organisers (de Boer, Koning & Mierau 2019). However, their goals and strategies are often dependent on prevailing social conditions (Wenner 2015).

Social

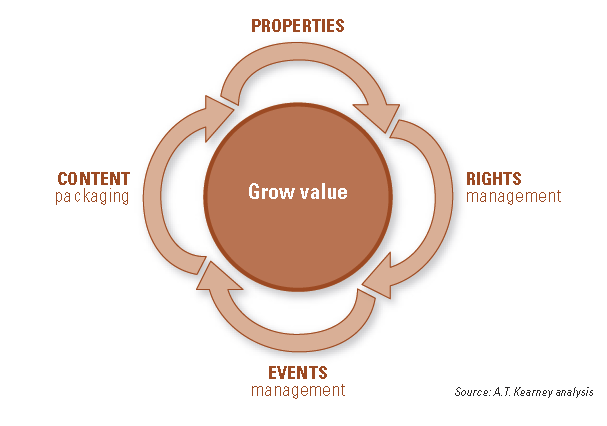

The social element of planning a large-scale sporting event is perhaps the most important external force affecting the sports planning process because games are social in nature (de Boer, Koning & Mierau 2019). This planning element has forced event organisers to structure major sporting events to generate the highest social value (Wenner 2015). For example, major events in the US, such as the NFL (Football), baseball (MLB), and hockey (NHL) generate about $23 billion dollars in revenue from media, sponsorship and gate collections (Collignon, Sultan & Santander 2017). These funds have also been used to support several social programs aimed at developing the different sports segments. Sponsors can also maximize the benefits of sports through value chain improvements. Figure 2 below shows the four key areas where sponsors could improve value creation: properties, rights (management), events management and content packaging.

By focusing on these four key areas of value creation, sponsors could maximize the benefits of sports events by treating the four pillars as part of a self-sustaining vicious circle of sports development. In addition, according to Müller and Gaffney (2018), sponsors can maximize the social benefits of sports events by integrating media channels in their business plans, utilizing social media tools to increase the effectiveness of their campaigns, creating exclusive content, and distributing them.

Several major sporting events have tried to maximise the value of different games by designing programmes that appeal to current social trends and patterns in entertainment and sports (Matthews 2007). Multiple social issues have also been highlighted in such events because of the need to address contemporary problems affecting societies (de Boer, Koning & Mierau 2019). For example, countries that host the FIFA World Cup strive to portray their cities as friendly places for tourism and living. The same finding is true for the Olympics, as demonstrated by Megheirkouni (2018). Their goal is usually to attract new investments and improve the profile or image of host countries (Schofield, Rhind & Blair 2018). Local communities that host large-scale sporting events also benefit from increased visibility on national and international stages. In other words, bidding for such events increases the profile of host cities because people learn more about them when they visit to watch the games. Therefore, it is common to find visitors sampling exotic dishes, studying local cultures and interacting with people from host communities after attending a sporting event.

Major games also attract a lot of media attention in host cities. This focus could be translated into monetary value if well exploited. Although the benefits of doing so are useful to the growth and development of local communities and their environments, Leeds and Sauer (2014) point out that the main challenge associated with understanding the positive impact of mega sporting events on communities is the difficulty in quantifying their benefits. Nonetheless, local communities can leverage their resources to increase their profiles when hosting prominent leagues. Indeed, as highlighted in this report, one of the most significant effects of hosting large-scale events is the direct foreign spending that visitors bring to the host city (de Boer, Koning & Mierau 2019). In other words, communities can leverage their competencies and attract millions of dollars in investments.

At the end of the games, these amenities are usually left under the care of local communities who use them as venues for hosting domestic sports leagues (de Boer, Koning & Mierau 2019). This outcome is not only unique to large-scale sporting events because small league games also have the same effect. Based on these assertions, Müller and Gaffney (2018) suggest that successful event management requires economic stimulation, so long as there is cooperation between sponsors and event planners. Comparatively, poor cooperation between the two parties could yield little or no economic growth (Müller & Gaffney 2018).

Technology

The technological aspect of this external environmental analysis is useful to the process of planning large-scale sporting events because organisers rely on this resource to meet their logistical needs (Finn 2016). In other words, it is difficult to supervise or oversee all aspects of operations without using advanced technological tools (Finn 2016). For example, the opening ceremony for the Olympics is heavily dependent on technology because it is characterised by spectacular events and performances, which require many lights, stages, music and technological effects. Therefore, it is almost entirely dependent on the availability of advanced technologies.

Relative to the above finding, social media marketing tools have also been used to enhance programme planning and event content development of mega sporting events (Brown et al. 2015; Finn 2016). For example, hashtags are vital in promoting positive content development. They are also useful in enhancing the programme planning process by improving the quality of event planning (Clavio & Frederick 2014). Therefore, fewer disruptions may occur because organisers would need minimal resources to organise their content. In addition, social media has been used to better organise data and increase awareness about the positive impact of a game (Finn 2016). However, the effective use of social media largely depends on the prevailing legal environment.

Legal

The link between the legal and political aspects of organising large-scale sporting events is undisputed because laws governing event management are partly informed by political trends (Brown 2015). For example, mega sporting events have partly been criticised as elitist projects meant to serve the interests of a few people in the society (Müller & Gaffney 2018). To affirm this fact, evidence has been given of many “white elephant” projects that have been initiated around the world and that have never realised their potential (Müller & Gaffney 2018). In addition, cases of mismanaged sports facilities explain why large-scale sporting events should be disregarded (Müller & Gaffney 2018). From an economic policy perspective, some people regard the process of financing large-scale sporting events as unnecessary expenditure, especially in countries or communities, which have other urgent developmental needs (de Nooij & van den Berg 2018). For example, the use of debt to finance sporting activities has been cited as one of the major criticisms of hosting mega sporting events because they leave the public worse off financially than they were before hosting the event (de Nooij & van den Berg 2018).

Large-scale sports may also be catalysts of international crimes, such as human trafficking because many sex workers travel to host destinations to solicit clients (Dimattei 2019). This trend has a negative impact on the community by contributing to the erosion of the moral fabric that binds families together. In addition, soliciting and human trafficking are illegal in many jurisdictions. Therefore, mega events could aid their occurrence by making it easier for criminals to masquerade as law-abiding citizens. Consequently, crime rates may increase when a city hosts an event (Dimattei 2019). Broadly, planning a large-scale event requires a proper understanding of existing laws and policies surrounding competition, fairness and events management (Brown 2015). Therefore, it is vital for organisers to be cognizant of the current legal environment to understand how it affects the planning process.

Environmental

Evaluating the environmental impact of large-scale sporting events is part of a larger global trend aimed at understanding the effects of man-made activities on the environment (Turken 2019). Different countries have developed unique laws to ensure the environment is protected and there is continuity in the approaches organisers use to plan their events. Therefore, event organisers are under pressure to minimise the environmental impact of their activities (Turken 2019). Environmental groups and lobbies that create awareness to the effects of events on climate change mostly advance this interest (Turken 2019). For example, some international agencies have claimed that the environmental impact of large-scale events is a common cause of concern for local communities because hosting them requires lots of energy and labour, which could increase carbon emissions (Turken 2019). For example, a rise in greenhouse gas emissions often occurs in cities that host events because of increased transportation costs. Therefore, the environmental impact of organising large-scale sporting events is a significant cause of concern for most environmental agencies (Turken 2019).

Although the negative effects of sports events are known, there is another side of the debate, which suggests that effective sports events planning nurtures environmentally friendly practices in local communities. Stated differently, sporting events also have a positive impact on the environment because they are predicated on the effective use of local resources to maximise the games’ social outcomes. For example, the use of public mass transport to ferry large numbers of people to and from sports venues is instrumental in improving the environmental record of host cities by encouraging its residents to embrace sustainability and efficiency through mass transportation (Raj & Musgrave 2009). Car-pooling is also another practice that could be linked with the event management process because it is informed by the need to transport a high number of people using one mode of transport. The above findings have been cited in published reports, which have relied on a post-impact assessment of past events (Turken 2019; Wojtys 2017). Such pieces of information have also been developed through the collaboration of sports agencies with independent groups of professionals, such as environmentalists (Turken 2019). Such collaborations have also helped to assess the impact of sports events on host communities.

Impact of Events on Host Communities and the Environment

How to Maximise Positive and Minimise Negative Impacts of Large-Scale Sporting Events

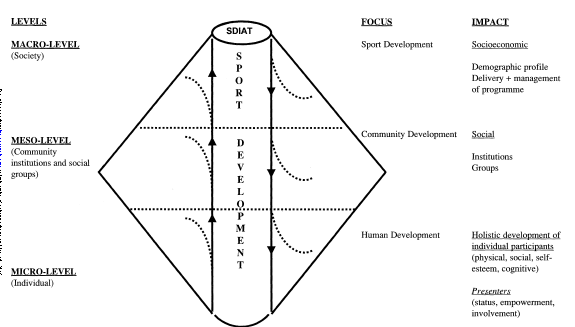

The positive impacts of large-scale sporting events on host communities and the environment are broad because they cover different aspects of social life. For example, according to Boonsiritomachai and Phonthanukitithaworn (2019), event planners are increasingly relying on sponsors to maximise the positive impact of sports by improving inter-community interactions because teams from different backgrounds often compete in sports, as opposed to engaging in socially destructive activities, such as crime. Figure 1 below suggests that the impact assessment of sporting events affects industry development (sport, community and human development), while interventions are often initiated at different levels.

Sponsor cooperation is a vital resource for maximising the positive and minimising the negative impacts of mega sporting events. For example, a strict approval criterion may be useful in recruiting sponsors who have a good environmental record. In addition, event planners could approve sponsors that have an effective corporate social responsibility (CSR) program and exclude those who have a poor environmental record. By adopting this strategy, they would be maximising the positive impact of sporting events on the environment by promoting the principles of environmental conservation and social protection. This outcome would suffice by working with companies that have a similar vision (Henderson & McIlwraith 2013). For example, hosting large-scale sporting events may attract positive social development initiatives in local communities because sponsors often pledge money to rehabilitate sports facilities in exchange for branding opportunities (Wojtys 2017).

Leveraging could also be instrumental in maximising the positive impact of an event if the organisers keep a percentage of the revenues to help sponsors achieve their goals. Bowdin et al. (2010) support this practice by encouraging event planners to assist their business partners improve their brand recognition objectives. This philosophy stems from the understanding that sponsors have to spend more than the fee paid to maximise their potential gains from participating in an event (Wojtys 2017). Based on the insights highlighted in this section of the paper, it is possible for event managers to minimise the negative and maximise the positive impacts of large-scale sporting events. However, the process should also involve measuring the impact of events. The subsection below delves into this issue in terms of two areas of events management: sponsor cooperation/leveraging and program planning and event content development.

Measuring the Impact of Events

Sponsor Cooperation and Leveraging

Method of Measuring Impact

Measuring the impact of large-scale sports events, in terms of sponsor cooperation and leveraging, refers to the process of evaluating whether the chosen event helps to realise the sponsor’s goals or meet the aim of hosting the event in the first place. The survey technique is the best method to use for data collection because of its representative nature (Donnelly & Arora 2015). Focus groups and interviews cannot be used to gather the same type of data because they are designed for use in small communities or using small numbers of informants (Donnelly & Arora 2015). However, sponsor cooperation and leveraging agreements are intended to have a massive impact on host communities and their effects can best be assessed using surveys. The spread and growth of the internet further makes this data collection method appealing to reviewing the impact of mega sports events on the population because it allows for the replication of surveys in different parts of the world (Donnelly & Arora 2015; Müller & Pickles 2015). Furthermore, surveys allow event organisers to collect data in real-time and encourage them to pair the analytical process with a reputable software tool, such as the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), which analyses large volumes of data (Donnelly & Arora 2015).

Techniques for Measuring Impact

Assessing the effects of sponsor cooperation and leveraging in large-scale sporting events on an economy, society or the environment requires a broad understanding of the main purpose of hosting them in the first place (Morgan et al. 2014). Their economic impacts could be reviewed using a resource-based method (Reid 2017). For example, it could emerge that an intensive use of resources would have a greater impact on the economy and a lower use of resources would have a lesser impact. This prediction could also be made in reverse to estimate the amount of revenue or resources that are generated through the implementation of sound sponsorship and cooperation agreements.

The resource-based view of evaluation is important in assessing the impact of mega sporting events because the technique is inherently economic in nature and has been used to estimate the efficacy of implementing event strategies (López & Kettner-Høeberg 2017). Its main disadvantage is its myopic focus on a small part of the evaluation (economic review), while the rest of the event evaluation criteria are neglected (Giulianotti et al. 2015).

Several other techniques could be used to measure the impact of mega sports events on sponsor cooperation and leveraging. One of them is the forecasting impact assessment. It refers to the quest by event planners to estimate the future impact of a sporting event. Historical data and consumer trend analysis are the main methods for undertaking such reviews (Schofield, Rhind & Blair 2018). A time series analysis is also a useful tool for forecasting the impact of large-scale sporting events because it could help researchers to understand the link between past and future impacts of an event (Theodoraki 2007; Giulianotti et al. 2015). This competency is derived from the fact that the technique analyses reliable data, which is usually plotted against time.

The main advantage of the time series analysis is its usefulness in understanding underlying factors that explain past and future trends. This technique is also appropriate for carrying out independent impact reviews by providing descriptive information about the future impact of an event. This piece of information is critical in creating an overview or holistic comprehension of an event’s impact. The key performance indicator used in a time series analysis is the period needed to predict outcomes accurately. In other words, the longer the schedule of time series assessment, the better the impact analysis. However, the main problem linked with this technique is the difficulty of ascertaining the accuracy of the time series plan in the long run. Broadly, forecasting impact assessments have been adopted in different event management processes and have widespread success in predicting their economic outcomes (Theodoraki 2007; Giulianotti et al. 2015).

The process of forecasting the impact of large-scale sporting events is linked with ascertaining the effects of specific actions taken during event planning. The methods and techniques that are useful in ascertaining this type of impact are predicated on computer-simulated techniques, which are vital in modelling the effects of the event on the community. For example, they may be instrumental in making accurate forecasts because they can compress a wide timeframe into a smaller analytical scope. In addition, simulation modelling can replicate real-life situations to provide the most accurate experience of an event’s future impact.

Performance Indicators

The number of messages sent within the host community could be a key performance indicator for assessing the impact of sponsorship agreements. Successful events often attract high frequencies of message transfers, while unsuccessful ones garner little attention from the public. Therefore, this type of assessment criterion may be used to predict the impact of an event on a community. However, the post-impact review of sponsor cooperation and leveraging should occur at the end of an event. This is because it is difficult to evaluate the impact of sponsor cooperation until the event ends because the commitment of sponsors should stretch beyond fee payments. Therefore, their relationship with event planners may transform from a financial to a nonfinancial one, depending on the sponsorship agreement terms. Nonetheless, the impact of such a transformation could be reviewed based on an evaluation of the real outcomes of the event, viz-a-viz the stipulated sponsorship contract.

When the sponsor delivers beyond what is outlined in the contractual agreement, it could be deduced that the event would have a positive impact on the host community. However, if they fail to meet the previously agreed standards of engagement, the relationships could be deemed inadequate or ineffectively implemented. The assessment technique to be employed in a post-impact review should involve the measurement of a key set of variables that were pre-agreed at the time of the contract formulation. They should also be monitored from the start to the end of an event. The post-impact assessment would then help programme evaluators to assess how well key deliverables have been achieved, or not. Collectively, these management tools are appropriate during impact assessment because they have been extensively used in business management literature and program planning (Theodoraki 2007; Giulianotti et al. 2015). Their main problem is the lack of specificity in event management. In other words, they stem from strategic planning literature and are applicable in event planning and management.

Program Planning and Event Content Development

Method of Measuring Impact

The focus group technique is the most preferred method for organisers to assess the impact of programme planning and event content development of mega sporting events. The method is appropriate because event content development and programme planning is often undertaken by a few people who can be assembled in a room and interviewed. Furthermore, before launching programmes, focus groups provide a sample population for testing its impact (Ellert et al. 2015). The focus group technique could be used to assess different issues relating to sports events. For example, it is a useful tool for organisers to make monetary quantifications of the impact of sports by analysing how event content would influence foreign direct investment flow into an economy (de Boer, Koning & Mierau 2019). The analysis may include a financial resource assessment of the event’s operations on host communities or a stakeholder review. Relative to this discussion, high levels of stakeholder buy-in would imply a correspondingly strong social influence of the event. Nonetheless, the following tools are useful in measuring the impact on the society.

Techniques for Measuring Impact

The methods and techniques for assessing the impact of mega sporting events in terms of programme planning and event content development are dependent on the involvement of third-party actors. For example, economists quantify the impact of sporting events on the economy, while environmentalists undertake the same review on nature. It is also common for event organisers to carry out their internal impact assessments to understand the effects of their activities on the economy, society and environment (Tum, Norton & Nevan Wright 2005). Using third party assessors is advantageous because there is no conflict of interest linked with the impact assessment process. Stated differently, the agencies that undertake them are only indirectly associated with event organisers. However, the inability to control when and how these independent groups undertake their reviews is the main impediment to seeking their expertise in evaluating the impact of mega sporting events (Schofield, Rhind & Blair 2018).

The environmental impact of large-scale sporting events can also be evaluated using the sustainable event model, which assesses how well sponsorship plans contribute to the attainment of environmental goals (Giulianotti et al. 2015). A sustainable development model is a useful assessment tool in this analysis because it draws attention to the improvement of auxiliary aspects of event management, such as the efficiency of event processes and resource conservation dynamics (Raj, Walters & Rashid 2013). In other words, by evaluating the sponsorship cooperation agreements and leveraging linked processes against the sustainable development model, areas of inefficiencies can be quickly identified and rectified. Such an outcome is feasible because the sustainable development model is self-checking and supports prudent resource use (Giulianotti et al. 2015).

Alternatively, the social impact scale analysis is useful in conducting an impact analysis of the event on the society because it helps to evaluate the extent that cooperation between event planners and sponsors generates a positive social impact (Tosa 2015). Alternatively, the economic impact analysis is applicable in evaluating the effect of an event, based on how well it stimulates economic growth. In this analysis, the level of economic stimulation emerges as a key performance indicator for evaluating the impact of mega sporting events. The strategic impact assessment of sponsorship cooperation and leveraging in large-scale sporting events requires an understanding of the effects of alternative policies on host communities (Tosa 2015). The appraisal could help to determine the number of patrons who attend such events and their impact on host communities.

Simulation modelling is another possible technique for measuring the impact of large-scale sporting events because of its capital-intensive nature. In other words, it is instrumental in understanding how an event’s complex systems interact with one another. Therefore, it is difficult to overlook how one aspect of event management could affect the broader planning process. However, one problem that may impede its use is the lack of sufficient data to develop a huge pool of information for conducting assessments (Pierce & Irwin 2016). This challenge has affected different aspects of the technique’s use. In addition to simulation modelling, the use of past data could be instrumental in predicting the effects of future sporting events on host communities.

Alternatively, a strategic impact assessment is another useful technique for evaluating the effects of alternative policies on event management. It helps project managers to make better decisions regarding which strategic choice to use in event planning (Rogers 2013). The main method for undertaking it is by understanding the wider environmental, social and economic impacts of a sporting event on the local community. According to Getz (2012), the strategic impact assessment should have eight stages of analysis, which include screening, scoping, impact assessment, formulating workable guidelines, evaluating alternative options, decision-making, monitoring and implementing the selected proposal (O’Toole 2011). These steps appeal to event content development because they are robust and commonly used in project planning (O’Toole 2011). Although they are applicable to big sporting events, the main impediment to implementation is the lack of formal procedures or guidelines for undertaking impact reviews (Giulianotti et al. 2015). In addition, the lack of a formal structure of assessment often makes it difficult to organise the review process.

Performance Indicators

A review of key performance indicators associated with mega sports events should focus on identifying the demonstrable attributes of a large-scale sporting event. These tenets of analysis may act as performance indicators to ascertain the effects of a sporting event on local communities. Most of the associated data are freely available. Therefore, there is no need to use sophisticated tools of review to understand the impact of a sporting event. However, a visitor exit survey could be used to assess the post-event effects of a game. This technique is a tool for collecting first-hand information from people who have attended a game. It is advantageous to organisers when planning an event’s programme because the information obtained from the data collection tool is more reliable than secondary sources of data, which may be predisposed to bias. The main advantage of this technique is that it allows event planners to make informed decisions about future events. At the same time, it engenders accountability in the event planning process by supporting the view that proper planning should be organised to create the most impactful outcomes.

Some key indicators that should also be considered for review include stakeholder buy-in and the time taken to make decisions. Stakeholder buy-in is an important concept to use for undertaking reviews because the process should involve all interested parties (Giulianotti et al. 2015). Therefore, the success of integrating different types of opinions in event planning may create stakeholder buy-in. Conversely, the presence of opposition would mean that some people may feel isolated. The time taken to make strategic decisions is also another indicator of performance because improved cohesion and collaboration among stakeholders mean that decisions are timely and effective.

Overall, stakeholder buy-in and the time taken to make decisions are important key performance indicators in impact assessment because they explain how fast decisions could be made and how effectively they may be implemented. The same observation has an impact on the development of event content because important decisions are often formulated during the planning phase. This type of collaborative strategy allows event planners to develop content that is appealing to a wide audience. Lastly, some key performance indicators that may also be applied to this area of evenet management (programme planning and event content development) include the number of sponsors, media hype generated from the events and the revenue accrued (Chen, Gursoy & Lau 2018). These indicators are both financial and nonfinancial in nature. Therefore, they outline a holistic assessment of an event’s impact.

Summary

This study has investigated the key features of mega sporting events and the possibility of maximising their potential impact on society. A discussion of the events sector has also been done using the PESTLE analysis and it has been revealed that organisers need to review several political, economic and social issues when organising them. For example, technological, political, environmental, social and legal factors have to be evaluated, vis-a-vis their impact on host communities. This paper has also outlined a discussion of how event planners could minimise the negative environmental factors of mega sporting events, with the aim of emphasising their positive impacts on the community. Evidence has been provided to show how sponsorships and leveraging could be assessed as reliable tools for improving and promoting the positive impact of mega sporting events. Information relating to the measurement of these positive and negative effects have also been provided through discussions that have highlighted strategic impact assessments, post-impact reviews, and forecasting analyses, as probable tools for measuring performance. This review informs the main recommendation of this paper, which is to improve cooperation among all stakeholders to make large-scale sporting events, as a subsector of events planning, more successful. Based on this suggestion, the future emphasis of event planning should be based on how to improve the planning process by tweaking the design phase to improve programme-planning processes and increase the cooperation of sponsors. These two key areas of event planning are instrumental in making mega sporting events more successful.

Reference List

Abson, E 2017, ‘How event managers lead: applying competency school theory to event management’, Event Management, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 403-19.

Allen, J 2002, The business of event planning: behind the scenes secrets of successful special events, Wiley Canada, Misssisauga.

Allen, J, O’Toole, W, McDonnell, I & Harris, J 2010, Festival and special event management, 5th edn, Wiley, London.

Aslan, A 2017, ‘Identity work as an event: dwelling in the street’, Journal of Management Inquiry, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 62-75.

Boonsiritomachai, W & Phonthanukitithaworn, C 2019, ‘Residents’ support for sports events tourism development in beach city: the role of community’s participation and tourism impacts’, SAGE Open, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 1-10.

Bowdin, G, Allen, J, O’Toole, W, Harris, R & McDonnell, I 2010, Events management, 3rd edn, Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Brown, A 2015, ‘Principles of stakes fairness in sport’, Politics, Philosophy & Economics, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 152-186.

Brown, C, Willis, E, Harvard, CT & Irwin, RI 2015, ‘From tailgating to Twitter: fans’ use of social media at a gridiron matchup between two historically black colleges’, Journal of Applied Sport Management, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 1-10.

Burnett, C 2016, ‘Social impact assessment and sport development: social spin-offs of the Australia-South Africa junior sport programmeme’, International Review for the Sociology of Sport, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 41-57.

Chen, K, Gursoy, D & Lau, KLK 2018, ‘Longitudinal impacts of a recurring sport event on local residents with different level of event involvement’, Tourism Management Perspectives, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 228-38.

Clavio, G & Frederick, E 2014, ‘Sharing is caring: an exploration of motivations for social sharing and locational social media usage among sport fans’, Journal of Applied Sport Management, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 1-10.

Collignon, H, Sultan, N & Santander, C 2017, The sports market, Web.

Cummins, RG & Gong, Z 2017, ‘Mediated intra-audience effects in the appreciation of broadcast sports’, Communication & Sport, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 27-48.

de Boer, WI, Koning, RH & Mierau, JO 2019, ‘Ex ante and ex post willingness to pay for hosting a large international sports event’, Journal of Sports Economics, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 159-176.

de Nooij, M & van den Berg, M 2018, ‘The bidding paradox: why politicians favor hosting mega sports events despite the bleak economic prospects’, Journal of Sport and Social Issues, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 68-92.

Dimattei, C 2019, The Super Bowl is coming to Miami in 2020. Sex traffickers are sure to follow, Web.

Donnelly, T & Arora, K 2015, Research methods: the essential knowledge base, Cengage Learning, London.

Ellert, G, Schafmeister, G, Wawrzinek, D & Gassner, H 2015, ‘Expect the unexpected new perspectives on uncertainty management and value logics in event management’, International Journal of Event and Festival Management, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 54-72.

Finn, J 2016, ‘Timing and imaging evidence in sport: objectivity, intervention, and the limits of technology’, Journal of Sport and Social Issues, vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 459-476.

Frawley, S 2016, Managing sport mega-events, Routledge, London.

Getz, D 2012, Event studies, 2nd edn, Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Gift, T & Miner, A 2017, ‘Dropping the ball: the understudied nexus of sports and politics’, World Affairs, vol. 180, no. 1, pp. 127-161.

Gillooly, L, Crowther, P & Medway, D 2017, ‘Experiential sponsorship activation at a sports mega-event: the case of Cisco at London 2012’, Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 404-25.

Giulianotti, R, Armstrong, G, Hales, G & Hobbs, D 2015, ‘Sport mega-events and public opposition: a sociological study of the London 2012 Olympics’, Journal of Sport and Social Issues, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 99-119.

Harris, R 2014, ‘The role of large-scale sporting events in host community education for sustainable development: an exploratory case study of the Sydney 2000 Olympic games’, Event Management, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 207-30.

Hartman, S & Zandberg, T 2015, ‘The future of mega sport events: examining the Dutch Approach to legacy planning’, Journal of Tourism Futures, vol. 1, no. 2, pp.108-116.

Henderson, E & McIlwraith, M 2013, Ethics and corporate social responsibility in the meetings and events industry, John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, NJ.

Ingle, S 2018,Government releases funding to help more athletes qualify for Olympics, Web.

Leeds, M & Sauer, RD 2014, ‘Editors’ introduction’, Journal of Sports Economics, vol. 15, no. 5, pp. 427-428.

López, B & Kettner-Høeberg, H 2017, ‘From macro to mega: changes in the communication strategies of the Vuelta Ciclista a España after ASO’s takeover (2008–2015)’, Communication & Sport, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 69-94.

Matthews, D 2007, Special event production: the process, Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Megheirkouni, M 2018, ‘Leadership and decision-making styles in large-scale sporting events’, Event Management, vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 785-801.

McDonnell, I & Moir, M 2014, Event sponsorship, Routledge, Oxon.

Morgan, A, Adair, D, Taylor, T & Hermens, A 2014, ‘Sport sponsorship alliances: relationship management for shared value’, Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 270-83.

Müller, M & Gaffney, C 2018, ‘Comparing the urban impacts of the FIFA world cup and Olympic games from 2010 to 2016’, Journal of Sport and Social Issues, vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 247-269.

Müller, M & Pickles, J 2015, ‘Global games, local rules: mega-events in the post-socialist world’, European Urban and Regional Studies, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 121-127.

Nufer, G 2016, ‘Ambush marketing in sports: an attack on sponsorship or innovative marketing?’, Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 476-95.

Ostrowsky, MK 2018, Sports fans, alcohol use, and violent behavior: a sociological review’, Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 406-419.

O’Toole, W 2011, Events feasibility and development, Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Parent, MM & Chappelet, J (eds) 2017, Routledge handbook of sports event management, Routledge, London.

Pierce, D & Irwin, R 2016, ‘Competency assessment for entry-level sport ticket sales professionals’, Journal of Applied Sport Management, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 1-10.

Pye, P, Toohey, N & Cuskelly, G 2015, ‘The social benefits in sport city planning: a conceptual framework’, Sport in Society, vol. 18, no. 10, pp. 1-23.

Raj, R & Musgrave, J (eds) 2009, Event management and sustainability, CABI, Wallingford.

Raj, R, Walters, P & Rashid, T 2013, Events management: principles and practice, 2nd edn, Sage, London.

Reid, G 2017, ‘A fairytale narrative for community sport? Exploring the politics of sport social enterprise’, International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 597-611.

Rogers, T 2013, Conferences and conventions: a global industry, 3rd edn, Routledge, London.

Schofield, E, Rhind, DJ & Blair, R 2018, ‘Human rights and sports mega-events: the role of moral disengagement in spectators’, Journal of Sport and Social Issues, vol. 42, no. 1, pp. 3-22.

Tasci, AD, Hahm, J & Breiter-Terry, D 2018, ‘Consumer-based brand equity of a destination for sport tourists versus non-sport tourists’, Journal of Vacation Marketing, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 62-78.

Theodoraki, E 2007, Olympic event organisation, Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Tjønndal, A 2018, ‘Identifying motives for engagement in major sport events’, International Journal of Event and Festival Management, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 223-42.

Tosa, M 2015, ‘Sport nationalism in South Korea: an ethnographic study’, SAGE Open, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 1-10.

Tum, J, Norton, P & Nevan Wright, J 2005, Management of event operations, Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Turken, S 2019, New initiative seeks to mitigate the environmental impact of Super Bowl on Miami, Web.

Tyson, B, Jordan, L & Truly, D (eds) 2016, Sports event management: the Caribbean experience, Routledge, London.

Weiner, E 2018, Government support is essential for sports owners and organizers, Web.

Wenner, LA 2015, Communication and sport, where art thou? Epistemological reflections on the moment and field(s) of play. Communication & Sport, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 247-260.

Wojtys, EM 2017, ‘The Brady Bunch’, Sports Health, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 204-204.

Yeoman, I, Robertson, M, Ali-Knight, J, Drummond, S & Mcmahon-Beattie, U 2004, Festival and events management: an international arts and culture perspective, Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Zhu, W & Wang, D 2019, ‘Leader-following consensus of multi-agent systems via event-based impulsive control’, Measurement and Control, vol. 52, no. 2, pp. 91-99.

Zimbalist, A 2016, ‘The organization and economics of sports mega-events’, Intereconomics, vol. 51, no. 3, pp. 110-11.