Introduction

In air transportation, safety is first. There have been contributions from sciences such as ergonomics, physiology, psychology, and the engineering sciences toward the aviation safety as the time goes by. The progress has grown gradually, however. The contribution of psychology to aviation safety is not an exceptional. There have been several schools of thoughts predominant at the time: 1) behavioural and cognitive psychology between early 1940s and mid 1970s which fostered understanding of human capabilities and limitations, 2) social psychology from late 1970s to late 1980s which directed our attention to small-group dynamics and which introduced Crew Resource Management (CRM) to further improve aviation safety, and 3) organizational psychology as the new, relatively “last frontier” in air safety in the 1990s that incorporates themes like corporate practices and its impact on actions of individuals, the aspects of secure and unsecured culture, the effect that organisational designs have on operational efficiency and role of tactical decision makers. Of late, both researchers as well as practitioners have started paying more attention to the construct of culture and the way it impact air safety. The latest development in the field is relevant to cross-cultural issues and their impact on safety which still requires further study and appropriate application in the airline industry as merger and acquisition of airlines is one of the key trends to promote the industry development.

This paper looks into cross-cultural issues and its relevant development in safety management system in an airline, namely, Qantas. First, the paper starts with an overview about the notion of culture in aviation. The paper addresses general definition, then discusses cultural issues in aviation, and then explores basic concepts of safety culture. Second, the paper will report findings in Qantas’ safety management system that has addressed the cross-cultural issues which have recently been raised as the new human factor consideration in aviation safety. Ultimately, the paper introduces about Qantas, the leading Australian carrier. Then the paper discusses about the company basic values, its policy in compliance with international laws. Next, the paper reports some findings on Qantas’ HF programs. Further, the paper briefed some of Qantas strategic intents abstracted from the company’s HR strategy and diverse workforce policy. In conclusion, the paper makes efforts to expand the scope for further study.

The Notion of Culture

When we talk about culture, we mean the values, customs, rituals, behaviours and belief which we share with others in order to create a relation being as a group. On the other hand organisational culture deals with shared values though there also we find assumptions, beliefs and customs but here it creates a relation with the organisational members. Hayward, (1997) while quoting Hofstede (1980) mentioned that culture is the collective programming of the human mind which makes one group different from the other.

Hofstede (1980) identified four cultural dimensions. First, Power Distance refers to social inequality and the amount of authority one person has over others. From a behavioural perspective, a strong Power Distance is observed which manifests in the form of reluctance to challenge the choices and activities of leaders regardless of their appropriateness. Second, Uncertainty Avoidance relates to how a culture deals with conflict, especially the creation of beliefs and institutions to deal with disagreements and aggression. Those cultures which score high in the dimension of Uncertainty Avoidance (Rules and Order) strongly believe that all rules and regulations must at any cost be abided, even in cases when it may be conflicting with a company’s interests or security circumstances. They also hold that well documented procedures should be in place for all circumstances and in addition, stringent time constraints must be applied to all activities. Low Uncertainty Avoidance score indicate that those cultures are more likely to transgress Standard Operation Procedures (SOPs). However, this may be advantageous when dealing with unprecedented circumstances by means of adopting new and innovative means to tackle the same.

Third, concept of Individualism & Collectivism denotes a bipolar construct wherein cultures tend to be towards the individualistic or collectivistic. Cultures which tend to be more individualistic in nature are formed by individuals who are more concerned only about themselves or their closely related associates. On the other hand, in cultures which are more collectivistic, it is observed that people tend to form in-groups or cooperatives wherein caring for others is valued and loyalty is expected in return. Those belonging to individualistic cultures pay more attention to self and individual gains whereas compliance with the group ideals is often observed in people belonging to collectivistic cultures. High Power Distance scores are often observed in collectivistic cultures, indicating disposed approval of unequal status and respect towards leaders. Lastly, Masculinity and Femininity stands for a bipartite construct which signifies two very dissimilar sets of social principles. From the masculine perspective, the most significant ideals are related to accomplishment and wealth. In the feminine standpoint, better quality of life and care and concern for others are looked upon as fundamental values.

Culture is also a major factor that affects behaviour. A conceptualization of the total situation is summarized in Lewin’s formula, B=f(PV x C), where B represents behaviour, a function of the interdependence between performance value (PV) and cultural background (C) (Yamamori and Mito, 1993). If a person’s cultural background does not agree with this person’s performance value, then the person’s behaviour will be affected. In aviation, there must be some kind of compromise between performance value and cockpit culture to get the behavioural results that will produce the safest and most efficient working environment in the cockpit.

Cultural Issues in Aviation

Helmreich (1999) stated that “ Culture serves to bind us together as members of groups and to provide clues and cues as to how to behave in normal and novel situations. “He also mentioned three cultures in aviation which surely impact safety: national culture, vocational or professional culture, and organizational culture.

National culture corresponds to the collective elements of national heritage. These take account of behavioural aspects, thoughts, and ideals. A few features of national culture which are acknowledged as significantly relevant to the aviation sector are Individualism / Collectivism, Power Distance and Uncertainty Avoidance or reverence for Rules and Order (Hofstede, 1980; Helmreich & Merritt, 1999). In a pertinent survey initiative carried out by Merritt (2000) in the course of his research, information was gathered from a sample constituted by 9400 male commercial airline fliers across 19 different countries. The initiative was a replication study concerning the Hofstede’s dimensions of national culture. The evaluation discounted the element of item equivalence. This turned out to be a better and more effective approach both on paper as well as in practice to appraise the Hofstede’s indexes and was more applicable to the formulae as stipulated. The effort brought out vital replication correlations with regards to all indexes. Following was the outcome of this effort:

- Individualism/Collectivism -.96;

- Power Distance -.87;

- Masculinity/Femininity -.75;

- and Uncertainty Avoidance -.68.

The productive replication corroborates that national culture has profound implications in terms of cockpit conduct in addition to the professional customs exhibited by pilots. In addition, it also substantiates that the axiom “one size fits all” cannot be applied to procedures when it comes to the issue of training.

Further, interaction amongst individuals of varying national cultures is frequently weakened by language related obstacles in addition to traditional values of the different cultures. Language oriented difficulties are although undesirable but a very much existent feature of culture. English being the principal means of communication may aggravate the difficulty. While individuals from various cultures have multi-lingual background, those belonging to Anglo cultures commonly converse only in English and may not be able to comprehend the difficulties experienced by those belonging to different cultures in grasping communication techniques in English. A straightforward answer to the difficulty based on lingual grounds is nonexistent but the reality needs to be confronted.

There is also a strong professional culture that is associated with being a member of a profession such as pilot. The good thing is the pride in a profession: when people love their work and are strongly motivated to do it well, then this can help aviation organizations work toward safety and efficiency in operations. There could be a negative component in pilot profession: they believe that their decision making endeavours are as productive under critical circumstances as ordinary situations, that their effectiveness is not dependent on individualistic predicaments, and that they are not more erring in a state of high strain. Next, establishments create and act according to their own conventions which closely reflect the day to day activities of their affiliates. Though national cultures are greatly opposed to alterations as they encompass a person’s societal traditions throughout the course of growing up, professional and organisational cultures can perhaps be tailored provided there are strong motivations underlying such a transformation. An organisation presents the carapace contained by which national and professional morals function and are a key causal factor of behavioural features. The most optimized impetus can be provided at the organisational plane in order shape up and preserve a safety culture. However, a determined and well perceived dedication of the top-level management in addition to effective policies fostering overt communications and interactions must requirements for the development and sustainability of safety cultures, whereas refutation of issues and disregard of risks can be detrimental to the same. Progressively, organisations are leaning towards a multi-cultural approach to a much greater extent. Individuals with various nationalities, operating in concert in the cockpit can give rise to language related problems inside the cockpit and can also hinder the communications between the aircraft and the external facilities. Even pilots may have varying backgrounds in terms of professional experience like working in military or civilian environments. Roberts, Golder, & Chick (1980) even suggested that the meaning of “pilot error” will be a cultural variable. Finally, because of widespread failures and mergers, individuals from very different organisational cultures may find themselves working together in a new organisational culture.

Barnette and Higgins (1989) and Weener (1990) proposed that, collectively, emerging nations have a crew factor accident rate up to 8 times that of industrialized nations as given in Table 1 below. Johnston (1993) explained that the correlation between socio-politicio-economic factors and accidents in the less-developed regions of the world hides a number of distinct influences: 1) an absence of investment in infrastructure and training, 2) a lack of regulatory expertise and independent monitoring of operators, and 3) a lack of suitable corporate and operational management expertise. Further, SOPs themselves are subject to cultural and sub-cultural variation (Degani & Wiener, 1991). Hofsteds’s central argument was that, given the distinctive cultural breakdown in work-related values, efficient work practices and group processes are likely to vary from country to country (Hofstede, 1980b, 1983, 1991).

Table 1. Regional comparison of crew factor accident rates (1980-1989) (Retrieved from Weener, 1990)

Safety Culture in Aviation

Wood (1996) noted that a practical characterization of Safety in the aviation business is rooted in the construct of tolerability of risk factors, asserting that, “if a particular risk is acceptable then we consider that thing or operation acceptable. Conversely when we say something is unsafe, we are really saying that its risks are unacceptable”. (Wood, 1996) In the words of Thomas (2001): “A low accident rate, even over a period of years, is no guarantee that risks are being effectively controlled….This is particularly true in organisations where there is a low probability of accidents but where major hazards are present. Here the historical record can be an unreliable or even deceptive indicator of safety performance”. (Thomas, 2001)

Hudson (2001) stated that an organisation’s Safety Culture is an evolutionary process from unsafe to safe and as such only after a certain point in development can an organization be said to take safety sufficiently seriously to have a safety culture. He broadly defined Safety Culture as “Who and what we are, what we find important, and how we go about doing things around here”; additionally Hudson linked the organisation’s culture and therefore it’s Safety Culture to its development evolution.

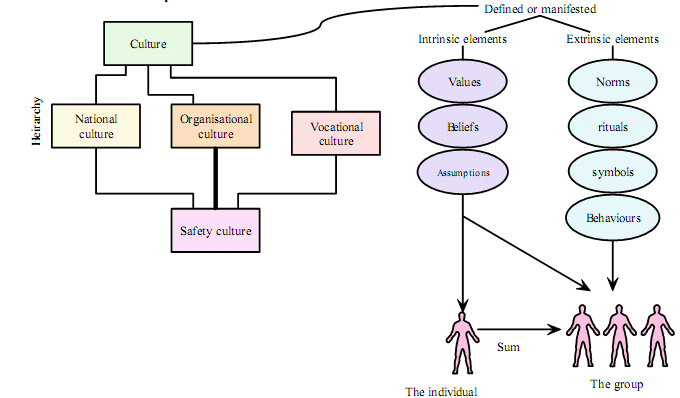

The traditional concept of culture is represented in Figure 1 and incorporates many of the features discussed above.

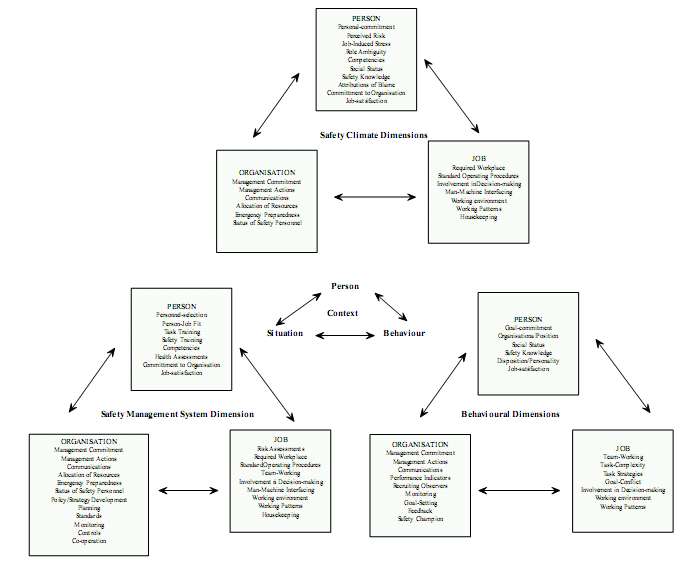

Cooper (1999) noted that there were three major components of Safety Culture: the individual, circumstances and behaviour. Amongst these three components, two components- ‘individual’ and ‘behaviour’ were explicitly considered while reflecting on the characterization of culture above where the emotional cognizance and behaviour aspects were in line with the internal and external factors. Further work on Cooper’s (1999) initial effort rendered his projected model that has been presented in Figure 2: the model is multi layered with the person, job and organization being replicated for the three main dimensions of Safety Management Systems, Safety Climate and Behaviour.

Qantas Airways

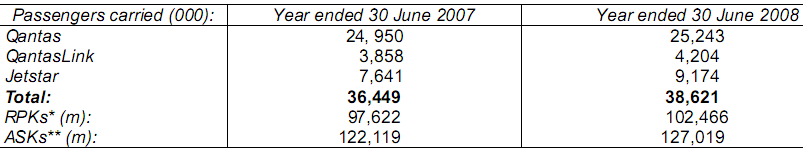

Qantas ranks only second in terms of number of years in operation for an airline company all across the globe. It was brought into existence way back in 1920 operating from the Queensland outback and at present has evolved into Australia’s principal and most prominent domestic as well as international airline. Qantas is also acknowledged as a top notch long distance airline service provider after having embarked on services connecting Australia to North America along with various European nations. The Qantas Group banks on the services of its nearly 36,000 employees and provides packages over a network encompassing 151 destinations spread across 38 different nations among which 58 are located in Australia itself and remaining 93 lying in different nations (counting those operated by code share collaborators) across all the continents. The Group’s operational statistics are given in the Table 2 below.

Below sections shall present details of Qantas’ initiatives in implementation of its safety management system addressing cross-cultural issues toward a sustainable safety culture.

Cross Culture & Its Implementation in Safety Management at Qantas

Qantas’ Values

In addition to the “Spirit of Australia”, safety is another symbol of Qantas. Open communication is the key as Qantas employees are encouraged to report all incidents that could affect operational safety. Qantas has recently organized the latest training programs for managing human error in areas such as engineering, flight operations and cabin crew (Qantas Annual Report 2008).

International laws compliance

Importantly, Qantas policies require compliance with all laws in the countries in which the Qantas Group operates. Qantas policies are regularly reviewed to ensure they show the highest standard in community and corporate expectations.

Human Factors Program at Qantas

When the Australian Aviation Psychology Association conducted its first international symposium at Manly in 1992 Qantas had commenced Crew Resource Management (CRM) training (Brown, Thatcher, & Jones, Undated). Australian aviation, Qantas included, have remained as the safest operating environment on the world stage. There is still room for improvement, however. A lack of serious safety incidents has the potential to reinforce a culture that Qantas is immune to accidents. As a result, it is difficult to introduce continuous improvement strategies when everything seems to be fine. Developments in Europe and in the US on CRM have led Qantas to reconsider its approach to human factors (HF) training which was included in a Qantas Flight Training development program named Advanced Proficiency Training (APT) started 1999.

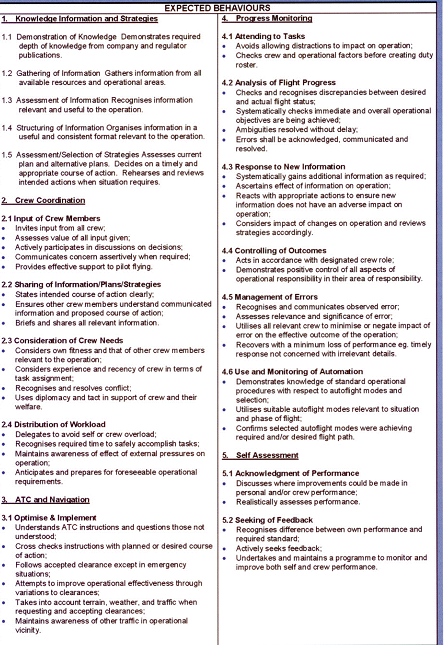

While Qantas has been good at training operating staffs in technical skills, it is the behavioural skills which need to be more clearly specified. In recognition of the potential impact of HF on Qantas business objectives, a Human Factor Steering Committee was formed in April 1998 to guide the extension of a new generation corporate HF program well beyond the cockpit to include error management across various operational divisions (Lucas & Edkins, Undated). This project was led by Dr. Graham Edkins, Manager of Safety Education and Human Factors. The expected behaviours of flight crew after the training is shown in Table 3.

Qantas Group Flight Training (QGFT), a divisional branch of Qantas, provides customers with advantages on account of its proficiency and amenities in place for operational training. To enhance safety considerations, the Qantas Group has adopted human feature courses so as to transform self-governing manners and approach by means of enhancing skills required for problem solving by the use of effective communication, adequate leadership qualities, good decision making capabilities and progressive cooperation. In 2002 the Flight Operations Pilot Mentoring Program was established and led by Captain David Coates who is Group General Manager of Qantas Group Flight Training.

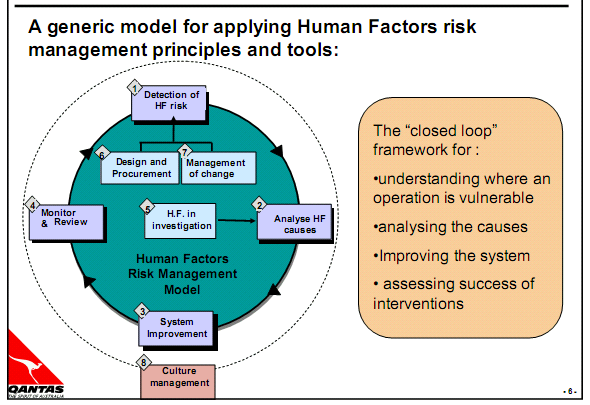

Raggett (2006) presented a new human factors risk management program for Qantas as shown below in Figure 3. Culture management regularly requires the subsequently mentioned measures: assessing the existent customs; distinguishing cultural impacts and impetus for transformation; designing cultural enhancement interventions; and tracking and reassessing at regular intervals. The temperament of these enhancement interventions may differ at times but also might incorporate, for instance, Just Culture interventions, Behaviour Based Safety interventions (BBS) (Clancy, 2006) in addition to efficiently developed safety leadership initiatives.

Qantas’ Human Resource Strategy

One of the most important sustainability issues that Qantas has been facing is shaping up and nurturing varied but competent employee strength. Qantas’ People Strategy concentrates on drawing in; developing and maintaining a talent pool by creating a gender and ethnically varied, multi-generational personnel base. This makes certain that the company is well equipped to contend with threats and vulnerability related to human resources, like an ageing staff and skill deficiencies, at the same time as sustaining economical labour expenditure. (Qantas’ Sustainability Report 2008, pp. 7).

One of Qantas’ initiatives is the launch of Qantas Swinburne Associate Degree Program. The Associate Degree initiative is a jointly conducted by Qantas and Swinburne University of Technology in Victoria. The first phase of the initiative consists of an Associate Degree of Aviation along with an academic and flight training program in conjunction with some educational curriculum concerning Aviation Human Factors and Air Transportation Management. This initiative needs the learner to be both a University undergraduate as well as a Qantas Cadet. So as to acquire the degree effectively, the Cadet has to perform consistently up to the standards in both platforms from the viewpoint of both Qantas as well as the University.

Another Qantas’ initiative is the company recruitment policy toward flight attendant. Candidates are encouraged to be influent in several languages such as Mandarin, Cantonese, Japanese, French, German, and Italian in addition to their English proficiency.

Qantas’ Diverse Workforce Policy

A diverse workforce is a key focus for the Qantas Group. It helps meet business need by showing internally the wide range of customers across the world. In 2005, a Diversity Council was established to sponsor this, with a particular agenda of increasing the representation of women in management at Qantas and supporting those in executive roles. In addition, Qantas aims to encourage young women in the community non-traditional occupations with the “Aiming High” workshop developed in conjunction with the New South Wales Premiers Department. Qantas has been active in Indigenous employment programs since 1988. It aims to use the Group’s effect to support and celebrate the diversity of Indigenous culture and to make a practical contribution to the reconciliation process in Australia. This year, Qantas’ own Indigenous Employment strategy has expanded to include a formal partnership with Reconciliation Australia, and to double the number of Indigenous staff employed at Qantas by December 2008.

Qantas investigates and takes seriously all claims of discrimination against or by employees/contractors or customers. Qantas has a solid policy foundation, with managers undergoing regular training to ensure they understand how to prevent and identify discrimination (Qantas’ Sustainability Report 2008, pp. 41).

Qantas’ cultural diversity in the kitchen

Qantas’ cultural diversity in the kitchen Qantas takes pride in the varied cultural diversity of its employee strength – a multiplicity that is transparently apparent throughout the Qantas Catering Group (QCG). In the Sydney chapter of its entirely possessed subsidiary, Q Catering, more than 70 per cent of the workforce having strength of 1,000 employees does not speak English as their mother tongue. This multiplicity factor provides a significant advantage in the industry and is particularly beneficial for a company that provides for a range of intercontinental cuisines. To warrant effectual communication of multifarious instructions and client, legislative and commercial requirements, Qantas instituted a Workplace English Language and Literacy (WELL) initiative back in November 2007. By means of this initiative, training would be provided to nearly 120 members of staff in the fields of Safety, Food Safety, Cultural Diversity and Customer Service and these trainees became proficient in the usage of such skills within a very short span of time. The trainees completed their training in November 2008. (Qantas’ Sustainability Report 2008, pp. 18).

Conclusion

In an increasing number of airlines multicultural flight decks are the reality of day-to-day flight operations. Hofstede’s studies on national culture from 1967 to 1973 identified specific cultural traits of various countries. Helmreich and Merrit conducted further studies between 1993 and 1997 on pilots from 23 countries and found out that substantial cultural difference among pilots from different countries as well as among pilots and their countrymen. The complex interplay between national, professional, and organizational culture on the flight deck does have effects beyond the recruitment process which needs to be considered to achieve the goals of safe and efficient flights.

There have been and will be great demands on recruiting and selection to find a pilot personality profile that can successfully manage the challenges of effective crew cooperation in a multicultural high-risk operational environment. Helmreich, Merritt, & Sherman (1996) found out that regardless of one’s national background, there has been a sort of “best practices” approach which changes cultural norms to fit the operating needs of the new multi-cultural environment. A more sensitive approach is to recognize the benefits and costs of cultural diversity and to include study of the nature of cultural differences in CRM programmes.

The Qantas case study indicates human errors can challenge every air carrier, even the best. The lesson learned is that continuous improvement is a must have for a carrier who can be proud of whose safety record.

References

Barnett, A., & Higgins, M. K. (1989). Airline safety: The last decade. Management Science, 35(2), 1-21.

Bartol, K., Martin, D., Tein, M., & Matthew S. (1995). Management. A Pacific Rim Focus. Sydney: McGraw-Hill.

Brown, I., Thatcher, S., & Jones, C. (2003). Systems safety in Australian general aviation – where are we now? South Australia: AERO Lab., University of South Australia.

Clancy, J. (2006). Achieving and Sustaining Safe Behavior. Melbourne: Action Conference.

Cooper, M. D. (1999). Towards a model of Safety Culture. Safety Science, 36(1), 111-136.

Degani, A. & Wiener, E. L. (1991). Philosophy, policies, and procedures: The three P’s of flight-deck operations. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium on Aviation Psychology (pp. 184-191). Columbus: Ohio State University.

Hayward, B. (1997). Culture, CRM and aviation safety. ANZASI: Asia Pacific Air Safety Seminar.

Helmreich, R. L., Merritt, A. C., & Sherman, P. J. (1996). Human Factors and National Culture. ICAO Journal, 51(8), 14-16.

Helmreich, R.L. (1999). Building safety on the three cultures of aviation. In Proceedings of the IATA Human Factors Seminar (pp. 39-43). Bangkok, Thailand: UTHFRP Pub.

Hofstede, G. (1980a). Culture’s Consequences: International Differences in Work Related Values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (1980b). Motivation, leadership and organizations: Do American theories apply abroad? Organizational Dynamics, 7(5),42-63.

Hofstede, G. (1983). The cultural relativity of organizational practices and theories. Journal of International Business Studies, 5(1), 75-89.

Hofstede, G. (1984). Cultural dimensions in management and planning. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 6(3), 81-99.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Cultures and organizations: Software the mind. Maidenhead, England: McGraw-Hill.

Hudson, P. (2001). Safety Management and Safety Culture. The Long and Winding Road. Canberra: CASA.

Lucas, I. & Edkins, G. (2001). Managing human factors at Qantas: Investing in a new approach for the future. Qantas Flight Safety. 3(3), 11-16. Sydney: Qantas Airways.

Merritt, A.C. (2000). Culture in the cockpit: Do Hofstede’s dimensions replicate? Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31(3), 283-301.

Merritt, A.C., & Helmreich, R.L. (1996). Creating and sustaining a safety culture. CRM Advocate, 1(3), 8-12.

Merritt, A.C., & Helmreich, R.L. (1996). Human factors on the flight deck: The influence of national culture. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 27(1), 5-24.

Raggett, L. (2006). A new human factor risk management program for Qantas. Presented at ess2006: evolving system safety – The 7th International Symposium of the Australian Aviation Psychology Association. Manly Pacific Hotel, Sydney Australia.

Roberts, J. M., Golder, T. V., & Chick, G. E. (1980). Judgment, oversight and skill: A cultural analysis of P-3 pilot error. Human Organization, 39(3), 5-21.

Thomas, M. (2001). Improving Safety Performance through Measurement. Paper presented at 5th Annual Residential Course for Effective Safety Management. 2001, Christ’s College, Cambridge.

Weener, E. F. (1990). Control of crew-caused accidents: The sequel. Boeing flight operations regional safety seminar, New Orleans. Seattle: Boeing Commercial Aircraft Company.

Wood, R. H. (1996). Aviation safety management programs: A management handbook. 2nd Edition. Englewood, Colorado: Jeppeson.

Yamamori, H. & and Mito, T. (1993). Keeping CRM is Keeping the Flight Safe. In E. L. Wiener, Kanki, B., G., and Helmreich R. L. (Eds.). Cockpit Resource Management. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.