How energy is stored in organisms as lipids

Lipids are the fats and their derivatives and are located in various regions of an animal’s body including in humans. They are mainly fatty acids and glycerols. They are compounds that are made up of bonded carbons, hydrogen and oxygen atoms. The long chains of CH2 make up the biggest portion of the fatty acids and a carboxyl or a methyl group may make up its terminal. A glycerol, on the other hand, contains a chain of three carbon atoms bonded to hydrogen and oxygen atoms. The formula for a glycerol is C3 H6 O3.

Excess glucose is stored in the form of fats and these fats are stored in the adipose tissue. When the animal is not eating, these fats are broken down by the enzyme lipase into glycerol and fatty acids. The fatty acids and glycerols are then further broken down to produce glucose. Glucose is a ready-to-use form of energy that is essential for the functioning of the organism (Bennett, 2008).

Compare saturated and unsaturated fatty acids

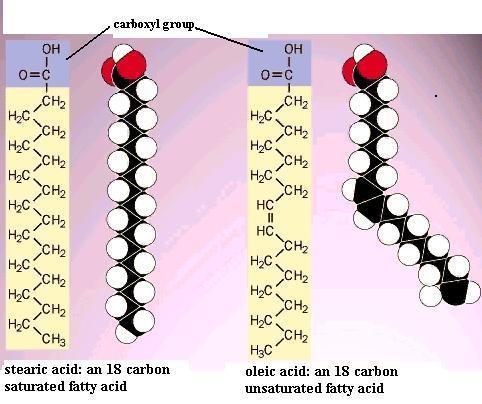

Saturated and unsaturated fatty acids differ in their carbon-hydrogen ratio. Saturated fatty acids are those fatty acids that are formed when all the carbon atoms within the chain are bonded to as many hydrogen atoms as possible. Their formula is Cn H (2n+1) CO2 H. Saturated fatty acids are those that have double bonds within the carbon, hydrogen and oxygen chain. They have the formula Cn H (2n-1) CO2 H.

The unsaturated and saturated fatty acids differ in their carbon-hydrogen numbers and also differ in terms of their melting points and energy content. Unsaturated fats have fewer carbon-hydrogen bonds and therefore, yield less energy than their saturated counterparts yield. Saturated fatty acids have a low freezing point because they can stack closely together. This explains why they are usually solid at room temperature.

Role of fatty acids in the body

Fatty acids play a big role in the organism’s body. One of the functions of fatty acids is to make part of the cell membranes. The membrane, made up of lipids, facilitates the fluid movement and transportation of the vital elements of the cell. Fatty acids, which make up part of the lipids, are essential for energy storage. This is facilitated by their anhydrous nature, which means that they do not contain water. The energy generated from the fatty acids more than doubles that which is generated from carbohydrates of the same quantity. This stored energy is not in a ready-to-use form. This enables the organism store it for a long time. Hibernating organisms use the energy from lipids to survive the difficult environmental conditions.

Fatty acids are also important for hormone formation since they form the bases of hormones. Lipids are also important in that they absorb and store vitamins in the fatty tissue. Organisms – for protection purposes – also use lipids (fatty acids). Plants, for example, use lipids to form the waxy coating on their leaves to prevent them from drying out. The same thing is observed for animals as they secrete oily substances on the skin.

Fluid mosaic structure of cell membranes

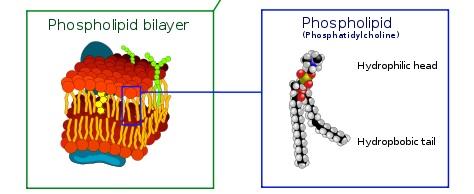

Lipids are important for the formation of the cell membrane. The cell membrane is made up primarily of lipids and proteins. The membrane allows for the transportation of molecules in and out of the cell. The fluid mosaic structure of the cell membrane consists of two layers of lipids and a layer of proteins embedded (Singer & Nicolson, 1972). The lipid bilayer is a self-constructed layer owing to the properties of the polar fluid. The amphipathic phospholipids at the membrane arrange themselves in such a way that the water-hating tail area is shielded away from the polar fluid around it. This causes the water-loving or hydrophilic region of the lipids to associate with the outer layer of the formed bilayer. The resulting form is a spherical shape made of a lipid bilayer.

How no-fat diets can affect the biochemical functions of the body

Taking of food without fats may turn fatal due to the body’s inability to perform some of the functions that are enabled by the presence of fats. Firstly, the body of the organism may lack the ability to absorb some of the essential vitamins such as vitamin K, D, E and A. These are the fat-soluble vitamins and need dietary fats to use them. A lack of these vitamins in the body leads to various diseases and conditions. These include night blindness, rickets and many more. The body’s immune system would also be deteriorated due to lack of these vitamins.

It has also been confirmed through research that a no-fat diet might affect mental health and likely cause depression (Maes, 1996). Research also suggests that low intake of essential fatty acids, which is caused by a no-fat diet, increases the chances of getting cancer of the breast, colon or the prostate. This is caused due to the lack of omega-3s in the body. No-fat diets also have a part to play in heart disease and the cholesterol level. This is because a diet without fat causes the good cholesterol (HDL) to reduce and the bad cholesterol to be accumulated in the liver in order to be excreted. Heart disease develops when the good and the bad cholesterol go out of balance. Therefore, fats are essential to the human body.

References

Bennett, L. (2008). The value of a high fat, high protein and no carbohydrate diet versus fasting in myocardial uptake in oncology studies. Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 49(1), 429-430.

Maes, M. (1996). Fatty acid composition in major depression: Decrease ὠ3 fractions in cholesteryl esters and increased C20:4ὠ6 ratio in cholesteryl esters and phospholipids. Journal of Affective Disorders, 38(1), 35-46.

Singer, S., & Nicolson, G. (1972). The fluid mosaic model of the structure of cell membranes. Science, 175(4023), 720-731.