Executive Summary

Stress at the workplace is a common phenomenon in many professions. However, unlike other professionals, correctional officers experience unique work dynamics that introduce new stress factors to their work experiences. Particularly, correctional officers have to manage and supervise the activities of people held by the state against their will.

Furthermore, most inmates have a record of violence. This paper explores the unique perceptive stress factors for correctional officers by focusing on five main categories of stress factors – external organizational factors, internal organizational factors, work environment factors, attitudinal variables, and demographic factors.

After sampling the views of correctional officers from Washington D.C and Baltimore City, this paper shows that work environment factors have the highest impact on occupational stress. Particularly, this paper identifies the dangerous nature of work for correctional officers as the highest contributor of stress. Therefore, to reduce the level of stress among correctional officers, this paper proposes the creation of a favorable work environment for correctional officers.

Introduction

Background

Workplace stress affects different professionals around the world. Finn (2000) says that about 30% of the general workforce experiences some type of stress in the workplace. Stress manifests as a psychological strain that affects people’s mental state. Unattended stress may lead to employee burnout, decreased organizational commitment, and low employee productivity (Finney & Stergiopoulos, 2013).

Employees may show its symptoms through frustration, exhaustion, and detachment (among other factors). The past decade has witnessed several attempts at explaining the main factors that affect stress. For example, several research studies conducted in the 1960s investigated the main causes of stress across different work categories (Brough & Williams, 2007; Finney & Stergiopoulos, 2013; Millson, 2000).

However, most of these studies focused on investigating stress factors across the most established industrial categories. Focus on human service sectors only emerged in the 1970s when researchers tried to investigate the real causes and solutions for stress across several work categories (such as police and nurses) (Millson, 2000).

At the same time, there were parallel attempts aimed at investigating the real causes of stress for correctional officers. Such studies aimed to identify and provide remedies for stress-related factors in the largest cohort on the correctional department – correction officers (Brough & Williams, 2007).

Cullen & Link (1985) say the focus on stress-related factors for correctional officers brought a new agenda in social research where correctional officers became worthy and interesting subjects for social studies.

Indeed, correctional officers were of great interest to many researchers because they supervised and managed the activities of a large population (inmates) that the government held against their will. Their job description also outlines the need to foster public safety by exercising human control as they interact and engage with prisoners.

Based on the nature and organizational structures of correctional facilities, it is inevitable for correctional officers to experience strict and pervasive bureaucracies that could contribute to their overall perception of stress. It is therefore unsurprising that the levels of stress for correctional officers are higher than other work categories. In fact, Lambert & Hogan (2010) say correctional officers record a 37% stress level, while employees from other job groups record a stress level of about 30%.

Brough & Williams (2007) say the symptoms of this high-stress level (employee dissatisfaction and lack of work commitment) comprise the greatest risks for the safety of correctional facilities. Similarly, Taxman & Gordon (2009) say a possible counterproductive behavior may manifest when correctional officers help detainees to carry out criminal activities within the correctional facilities. However, to prevent these adverse outcomes, it is important to understand, first, the nature of stress for correctional officers.

The Problem

Sources of stress often vary across different professions. People do not have the same experiences and effects of stress. Most social studies have focused on explaining work-related issues that affect employee productivity and turnover (Finney & Stergiopoulos, 2013; Millson, 2000).

Few studies have however bothered to investigate the experiences of correctional officers in their work setting. Unlike other work environments where officers interact with other people, correctional officers unique work circumstances because they interact with people held by the state against their will.

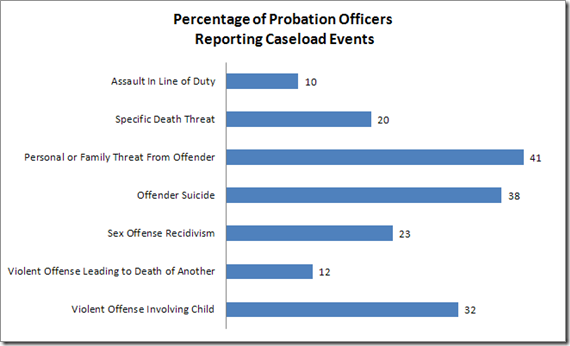

Moreover, the nature of interaction between a correctional officer and an inmate is subject to daily meetings that often arise in negative interactions. These factors mostly make the nature or work for correctional officers to be risky and dangerous. Figure 1 shows incidences where correctional officers have been assaulted in the line of duty, received death threats against their lives and the lives of their family members.

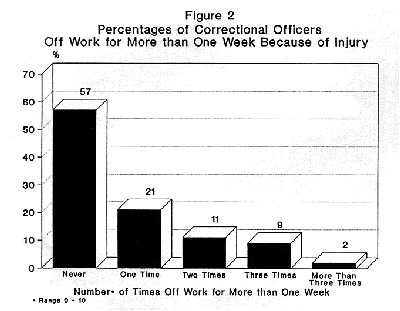

Figure 2 shows that many officers have also missed work because of injuries inflicted by inmates (some officers have missed work up to three times in a year because of such incidences). The adverse nature of relationships between correctional officers and inmates therefore provides a new layer of possible stresses that distinguish them from other professionals who interact with people.

Arguably, the conditions that correctional officers face in their work environments are more severe than other professions. The unique dynamics that correctional officers experience in the workplace create a special focus for this paper because this study strives to fill the gap in literature regarding the unique experiences of correctional officers, viz-a-viz other professions. To do so, the present study strives to understand the predictors of occupational stress among correctional officers

Research Aim

To understand the predictors of occupational stress among correctional officers

Research Objectives

- To investigate the impact of demographic factors on the occupational stress of correctional officers

- To understand internal organizational factors that affect occupational stress for correctional officers

- To comprehend the effect of external organizational factors that affect occupational stress for correctional officers

- To evaluate the impact of work environment dynamics on the occupational stress of correctional officers

- To assess the magnitude attitudinal factors of correctional officers have on their stress levels

Purpose of Study

By understanding the predictors of stress for correctional officers, it would be easier to prevent any adverse outcomes that may arise from increased stress levels among the state officers. Particularly, it would be easier to reduce levels of crime in correctional facilities because many researchers affirm a link between stressed officers and increased crime in such facilities (Brough & Williams, 2007; Finney & Stergiopoulos, 2013; Millson, 2000).

Furthermore, since suicide among stressed officers is a common phenomenon, an understanding of the predictors of stress for correctional officers would help to reduce this phenomenon. Broadly, the findings of this study may help to inform the process of formulating successful interventions that would help stressed officers to overcome their plight. Stated differently, it would be easier to provide focused interventions that would have a high efficacy if people use the findings of this study to detect and treat stressed officers.

Literature Review

Historical Review

To understand stress-related issues for correctional officers, many researchers have applied different models and theories to explain the experiences of correctional officers in the work setting. Several attempts at studying the impact of occupational stress on correctional officers have led to a growing body of knowledge in this area of study.

This section of the paper provides a framework for understanding disparate stresses by analyzing five core sources of occupational stress – external, internal, attitudinal, work, and demographic sources of stress. Lastly, this study analyzes the theories surrounding occupational stress factors.

External Organizational Factors

Studies that focus on the effect of external organizational factors on correctional officers are scanty. Instead, many researchers have focused on studying intra-organizational factors, such as poor communication, organizational hierarchy, poor management support (among other factors), in understanding how occupational stress influences correctional officers.

Although some of these indices appear in later sections of this paper, it is important to mention that most studies that have focused on external factors affecting occupational stress on correctional officers have concentrated on evaluating people’s perceptions of correctional officers and the pay that the officers get (Millson, 2000).

Publicly, the media portray correctional officers (mostly in films and movies) as stern disciplinarians and brutal officers who would not hesitate to punish offenders. Such perceptions have created a sense of misinformation about correctional officers. In fact, Millson (2000) argues that such misconceptions have made some officers to be embarrassed about their profession, thereby treating it with a lot of secrecy.

Recent studies have focused on understanding the community’s view of correctional officers by attempting to understand if there is a changing perception about the profession (in the public’s eye). For example, Abdollahi (2002) conducted a study to evaluate this issue by interviewing about 266 correctional officers in several correctional facilities in the US.

The respondents received self-administered questionnaires to report about the community’s respect for their profession and the respect they receive in the same regard (the study used these measures because they were the best predictors for evaluating employee burnout and job satisfaction) (Abdollahi, 2002). Related studies have focused on addressing the impact of low pay for correctional officers by citing it as a common factor that leads to increased stress levels among correctional officers.

In one study, Hogan & Lambert (2006) reported a high level of stress for correctional officers that pursued a second job to make ends meet. Similar studies show that most officers are willing to work overtime to supplement their incomes (Stergiopoulos & Cimo, 2011). Although many researchers affirm the impact of external sources of stress on correctional officers, the majority of them believe these external stresses are products of internal failures.

Internal Organizational Factors

Most studies focus on internal causes of occupational stress among correctional officers. Such studies have shown that organizational factors and managerial expectations are the greatest contributors of occupational stress. Relative to this observation, Millson (2000) says some common issues that also emerge in such studies include, “understaffing, overtime, management support, career progression, communication and decision-making, and role conflict and ambiguity” (p. 16).

Stergiopoulos & Cimo (2011) say all these indices have an effect on occupational stress. However, their effects (degree of correlation) vary. For example, Millson (2000) says management support and career progression have the highest level of correlation with occupational stress. A study that evaluated the views of 1,750 correctional officers in the US (cited in Millson, 2000) established that career progression had a very strong correlation with occupational stress.

Except for feelings of personal security, a study by Abdollahi (2002) shows that career progression accounted for a significant variance in occupational stress (personal feelings of security accounted for 19% of variance, while career progression accounted for about 7% of the variance). Abdollahi (2002) also says understaffing and the involvement of officers in decision-making have the least effect on occupational stress.

Attitudes Towards Correctional Work

Researchers who have investigated the impact of work attitudes on occupational stress have mainly concentrated on understanding correctional orientation and job satisfaction (Millson, 2000). Intuitively, many researchers say correctional officers who have high levels of job satisfaction report low-stress levels (Millson, 2000).

Furthermore, Neveu (2007) and Kienan & Malach-Pines (2007) say job satisfaction has a negative correlation with occupational stress. Studies that are more specific about the different roles of correctional officers show that front-line employees of correctional facilities report the highest levels of occupational stress (Kienan & Malach-Pines, 2007).

Correctional orientation is also another important dynamic of attitudinal behaviors that affect occupational stress among correctional officers. This orientation stems from a shift of roles where correctional officers do not only play the role of providing security at correctional facilities but also play a new role of helping inmates rehabilitate.

A growing body of literature affirms this shift (from advocating for punitive measures to advocating for rehabilitative measures) (Millson, 2000). This attitudinal diversity has created a lot of curiosity among sociologists ass they strive to understand how the correctional re-orientation of correctional officers affects occupational stress (Millson, 2000).

Lambert & Hogan (2007) argue that an orientation towards custody is synonymous with stress. In other words, correctional officers who experience high levels of stress prefer to adopt a custodial approach to reduce their level of stress. Lambert & Hogan (2007) also say that most correctional officers are generally inclined to adopt a custodial approach that may manifest as resentment towards inmates or the advocacy of punitive actions for offenders.

Interestingly some studies show no correlation between correctional orientation and occupational stress. Millson (2000) argues that correctional orientation is highly related to job dissatisfaction, but not occupational stress.

Therefore, such studies show that most officers who are inclined to adopt a punitive attitude in their responsibilities are more likely to report high levels of job dissatisfaction. Studies by Lambert & Hogan (2007) (using the Klofas-toch measure) also reported similar findings when they found out that, “counseling roles, concern with corruption of authority, social distance, and punitive orientation” did not affect occupational stress” (p. 45).

Demographic Factors

Studies that have focused on understanding the effect of demographic characteristics of occupational stress have mainly focused on using gender, education, and age as the main indices of this analysis (Millson, 2000).

Studies that have focused on age as an indicator of stress have shown highly inconsistent findings. For example, Armstrong & Griffin (2004) found out that age had a direct correlation with occupational stress, but Millson (2000) postulates that age does not have a direct correlation with stress (as measured by total exhaustion scores).

Studies that show a direct correlation between age and stress also show that younger officers report lower levels of stress than older officers do (Millson, 2000). Interestingly, similar studies report that older officers report lower levels of stress in the workplace because they adapt better to their work environments, as opposed to younger officers (Armstrong & Griffin, 2004).

Studies that have focused on gender show that gender also shares a direct correlation with occupational stress because female correctional officers report higher levels of stress than their male counterparts do (Griffin, 2007).

Using a stratified sample of about 1000 correctional officers drawn from 39 correctional facilities, Millson (2000) disputed the above findings by saying men and women experience the same level of stress. Millson (2000) further said that such results should not be surprising because most work environments today are progressive and therefore offer the same working conditions for both genders.

Besides gender, studies that have used education as a predictor of stress have always advocated for a cautious understanding of their findings (Robinson & Porporino, 1997). However, most of them say educated officers are likely to report higher levels of stress than officers who are less educated.

The reasons advanced for such findings stem from high expectations about the work environments and unrealistic career expectations that may be unmet in their work environments. Such analyses highlight the cautiousness that most analysts need to accord such findings because, as Robinson & Porporino (1997) purport, these educational cohorts may be responsible for moderating stress levels, and not the mere understanding of education as a predictor of stress.

Comparatively, some studies show that there is no significant difference between occupational stress levels for educated and uneducated people. For example, Millson (2000) suggests that education is a not a strong predictor of educational stress. Similarly, Millson (2000) says there is not much difference in the occupational stress levels for officers who have completed their education and those who have low educational qualifications.

Lastly, previous research also focused on job experience as a predictor of stress. Most of such researchers have combined age and years on the job as the best predictors of occupational stress (Millson, 2000).

Lavigne & Bourbonnais (2010) say the analysis of work experience is critical because it is a strong predictor of employees’ job conditions and work environments. Unlike other studies that have shown conflicting results regarding demographic factors and occupational stress, most of the researchers who have investigated work experience and stress levels show that the two variables have a strong correlation (Millson, 2000).

For example, Lavigne & Bourbonnais (2010) say correctional officers who have experienced continual employment report high levels of stress. Regression analyses conducted to understand the same relationship also show a high level of the predictive equation between both variables (Lavigne & Bourbonnais, 2010). Interestingly, most of such results show a high correlation between occupational stress and work experience and not on job dissatisfaction and a general sense of stress, as other studies do.

Work Environment

Studies that have investigated the impact of internal organizational factors of occupational stress have focused on investigating the nature of work, inmate interactions, and boredom as significant predictors of occupational stress. Concerning boredom, several researchers report that this index is a moderate predictor of stress among correctional officers (Millson, 2000). Analysts regard the independent and solitary nature of officer activities as the primary cause of employee boredom in the workplace (Lavigne & Bourbonnais, 2010).

Moreover, since the duties of correctional officers follow a strict routine, many of the officers may easily get bored. Interactions with inmates have often merged with the dangerousness of officer duties to explain occupational stress because many correctional officers believe their interactions with inmates expose them to unknown danger. Most of them cite this issue a stress-causing facto (Lavigne & Bourbonnais, 2010).

A survey by Millson (2000) to explore the views of more than 900 correctional officers highlighted the danger of their work as a key predictor of stress. Here, Millson (2000) explains that stress means, “The general milieu of working in correctional settings” (p. 26).

Bourbonnais & Jauvin (2007) say this correlation should not be surprising because many correctional officers interact with people who have a history of violence. Furthermore, correctional officers are supposed to ensure inmates perform duties that are often against their wishes (such actions may aggravate their violent nature). The dangerous nature of job roles therefore stands out as a significant predictor of stress.

Theories

Historically, researchers say the potential of a theory to measure and predict a scientific phenomenon greatly depends on the accuracy of data collected to formulate the theory (Millson, 2000). Although many researchers have advanced different theories that explain occupational stress, this section of the paper focuses on the most significant types of occupational theories. They outline below

Identity Theory

The identity theory suggests that most adults create their identities based on their daily activities. Since most of these activities occur within the normative expectations of social behavior, people’s performances, viz a viz these expectations, have a very profound impact on how they evaluate themselves. Carlson (2008) says that stress plays a vital role in evaluating a person’s performance because it affects their abilities to fulfill a specific social role.

Paoline & Lambert (2006) also say that job stress has a direct link with the identity theory because job involvement represents a direct cognitive involvement with a person’s psychological identification with a job. Therefore, from this analysis, job involvement represents a person’s involvement between job-related stress and personal identity. This is because job-related stress normally occurs to people who consider their work as a tenet of their identities.

Although the identity theory has shown merit in understanding how occupational stress relates to work, some researchers believe it is ineffective in explaining the depth of this relationship because of the difficulties in measuring job involvement and relating the same measurement to job stress (Paoline & Lambert, 2006).

It is however important to show that intra-personal and interpersonal relationships may still affect the interaction between people’s occupations and stress (some researchers question the ability of the theory to explain the underlying causes of work-related stress).

Person-Environment Fit Model

The person-environment (PE) fit model is among the most commonly cited models for understanding the relationship between occupational stress and employees’ psychological state of mind. The PE fit model postulates that the failure of the work environment to fit in an individual’s psychological cohort may lead to unmet needs and unmet job demands (Millson, 2000). These undesirable outcomes cause stress.

The misfit between individual needs and work environments therefore means that occupational stress may reduce by minimizing this misfit (Castle & Martin, 2006). If we extrapolate this finding to the work environment, we see that occupational stress occurs from the unproductive interaction between people and their work environments.

Stated differently, Millson (2000) says, “Occupational stress occurs when job demands that pose a threat to the worker contribute to an incompatible person-environment fit, thereby producing stress” (p. 10). Lambert & Paoline (2010) say when most workers face these occupational stress factors, they often rely on internal and external stress factors to manage this stress by striving to strike a balance between their individual needs and the needs of the workplace environment.

While the PE fit model has contributed immensely to the knowledge surrounding work environments and individual stress, some researchers criticize it for failing to provide a specific analysis of this phenomenon (Lambert & Paoline, 2010). Moreover, Castle (2008) posits that serious methodological limitations undercut the validity of the theory in understanding occupational stress.

Some of these methodological limitations include, “Inadequate distinctions between different versions of fit, confusion of different functional forms of fit, poor measurement of fitness components, and inappropriate analysis of the effects of fit” (Millson, 2000, p. 10). Nonetheless, despite the existence of these criticisms, it is crucial to show that the criticisms surround the application of the theory and not the theory itself.

Recent findings address some of the limitations for the shortcomings of this model and prove that the model can sufficiently predict the level of fit between employees and their work environments (Millson, 2000). Certainly, so long as researchers continue to address the methodological problems of this theory, future research may continue to rely on this theory to comprehend occupational stress and its impact on employees.

Demand-Control Model

Finn (2000) says the demand control model helps to understand the relationship between the joint effects of demand and job control (plus its effect on predicting stressful outcomes in the workplace). Recent analyses of this model show that occupational stress only intensifies when the relationship between job control and job demands increases. Stated differently, the model posits that the highest stress levels exist in highly stressful work environments.

Such high levels of stress especially manifest when workers lack adequate control over their duties. Comparatively, low-stress levels occur in work environments that have low employee demands and the employees have a high control of their duties (Finn, 2000). Millson (2000) also says passive jobs create intermediary stress levels for employees. Such passive jobs may include low stress and low control, or high stress and high control.

Although assessing an employee’s level of stress is a key tenet of the demand-control model, Millson (2000) says three hypotheses are pivotal to the understanding of the same model – iso-stress hypothesis, active learning hypothesis, and the dynamic demand-control hypothesis. The iso-stress hypothesis postulates that most employees who work in socially isolating environments and face highly stressful environments (with low control) are most likely to report the highest levels of occupational stress (Millson, 2000).

The active learning hypothesis is different from the iso-stress hypothesis because it predicts that the highest motivation levels exist in work environments where employee skills/control matches their job requirements. The dynamic demand environment differs from the above hypotheses because it considers the effect of the work environment of the employees, over a long period.

For example, Finn (2000) says this hypothesis posits that an overexposure to the work environment may lead to the development of feelings of mastery among employees. Such feelings of mastery may affect the level of stress by minimizing it. The hypothesis also posits that an overexposure to daily residual stress, over a long time, may lead to the creation of anxiety and depression among employees. This outcome may increase their stress levels, encourage them to avoid job challenges and force them to abandon their jobs.

Evidence gathered from the demand-control model shows that the model is useful in understanding the relationship with the work environment and an employee’s level of stress (Finn, 2000). Despite the fact that some criticisms exist within the context of implementing the control construct, recent advancements of the model have addressed this issue.

For example, Summerlin & Oehme (2010) addressed issues of autonomy and control by saying that these factors are important in analyzing employee perceptions of stress. Moreover, the same factors are instrumental in helping employees to overcome their stress. Lastly, the model is also useful in addressing different types of jobs (job demands) and understanding issues in the work environment that may lead to an enhancement of employee stress (job factors).

Research Hypothesis

Work Environment Factors contribute the greatest indices of occupational stress

Methodology

Subjects

This study sampled a group of ten correctional officers from Washington D.C and Baltimore City. The paper chose a minimum sample because of the need to optimize confidence during the data collection process. In detail, the present study chose this sample size to provide a minimum confidence interval of about five percentage points (95% confidence level).

An equal number of respondents came from both regions because five respondents came from Washington D.C and the other half came from Baltimore City. The intention of striking a numerical and gender balance in the selection of the respondents was to gather a representative sample of the predictors of occupational stress among correctional officers.

Instruments

This study used a set of self-administered questionnaires to collect data from the ten respondents sampled in the study. After the respondents completed the questionnaire, they sealed it in a folder titled, “confidential.”

The participants also had the option of mailing the questionnaire to the researcher, but none of them chose this option. The dependent and independent variables emanated from the findings of the literature review section. The research analyzed the respondents’ views based on the five major categories of stress that affect correctional officers.

The main categories were external factors and international factors that affect correctional institutions and correctional officers. Work environments and demographic factors also outlined another category for understanding the views of the respondents, while work attitudes outlined the last category of analysis. This study used a seven-point Likert scale to gather the respondents’ views. The scale varied from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.”

The dependent variable was job stress. Other studies that have used this type of measure for assessing occupational stress among correctional officers have shown a high level of internal consistency (Brough & Williams, 2007; Finney & Stergiopoulos, 2013; Millson, 2000).

This consistency has especially been reliable when measuring job stress, relative to empathy and punishments. Indeed, two studies reported by Lambert & Hogan (2008) and Millson (2000) show a high level of internal consistency based on the reports on alphas studies.

Since researchers have reported this high level of internal consistency across different parts of the world, it is true to say, the job stress scale is reliable across different settings. This fact provides sufficient grounds to believe the job stress scale was highly reliable for this study.

Procedure

The main research design was quantitative. This is because the study gathered responses through a predetermined framework of analysis. Because of the need to provide a gender balance among the respondents sampled, the research used purposeful sampling. Before providing the questionnaires to the respondents, I ensured the participants understood that the survey would be confidential and anonymous.

The respondents also understood that the researcher would be the only person required to see their responses. Here, the hope was to make the respondents feel comfortable to participate in the study. On the day of the research, the respondents received the questionnaires after their managers allowed them to do so (by borrowing some of their working time). The respondents completed the questionnaires in about 30 minutes. The study used the stepwise regression analysis to analyze the data collected.

Statistics

Initially, the intention of this study was to interview five men and five women. However, only four women participated in the study (one female respondent was unable to do so for personal reasons). In sum, six male officers and four female officers participated in the study. Their mean age was 35 years.

Results

All the respondents agreed to participate in the study by completing a self-administered questionnaire. The response rate was therefore 100%. Although this study used a small sample of respondents, other regional and national surveys on correctional officers have reported low response rates (Brough & Williams, 2007; Finney & Stergiopoulos, 2013; Millson, 2000).

For example, a federal study to evaluate the attitudes of correctional officers across 47 correctional institutions reported a response rate of 41% (Millson, 2000). In another study, researchers reported a response rate of 46.9% after sampling the views of correctional officers from seven adult and juvenile correctional facilities (Finney & Stergiopoulos, 2013).

Nonetheless, after evaluating the responses given by the informants of this paper, it is correct to say most of the respondents reported a neutral range of answers to questions that evaluated the effect of various types of stress factors at work. Stated differently, an almost equal number of respondents rated the items as “agree” and “disagree.”This finding is important for the formulation of the overall findings of this paper because it shows an equal variety of results.

An evaluation of the external factors affecting occupational stress showed the poor public image and low pay as having a stronger correlation with occupational stress than the lack of public accountability.

Most of the respondents said they agreed that poor public image and low pay contributed to their stress levels, but only two respondents polled the same about the lack of accountability. The two respondents therefore believed that the management of the correctional facilities should be more accountable to the public about their activities.

Nonetheless, an evaluation of work environment dynamics showed the most profound results from most of the respondents (except one) said they “strongly agreed” that personal security and staff empowerment affected their stress levels. Poor training and the failure to understand work procedures showed a dismal correlation with occupational stress.

More so, most of the respondents were undecided about the effect of the failure to understand work procedures on occupational stress. However, half of the respondents believed poor training was a contributor of stress.

An analysis of the demographic factors affecting stress showed no correlation of age and gender with stress. In fact, most of the female respondents (except one) strongly disagreed with the fact that gender affected their stress levels. However, seven respondents partially agreed that the lack of education contributed to occupational stress.

An analysis of the internal factors affecting occupational stress shows a significant correlation between strenuous work shifts and occupational stress. The lack of growth opportunities and job security also showed a significant correlation with occupational stress. However, most of the responses showed that the officers either agreed or partially agreed with this relationship.

An analysis of the attitudinal variables showed that job satisfaction had a negative correlation with occupational stress. Interestingly, very few respondents agreed that there was a link between correctional orientation and occupational stress. Regarding the criterion validity for the dependent variable, the paper used a correlation analysis to examine the likelihood of job stress, by evaluating job satisfaction, and lifestyle indicators.

The analyses showed that the correctional officers with the highest stress levels reported the lowest levels of job satisfaction. This finding supports the view of other researchers who have reported a high level of job dissatisfaction for employees with high-stress levels. Lifestyle and health factors also emerged as important indices in past analyses because past research showed a high correlation between them and occupational stress (Stergiopoulos & Cimo, 2011).

Lastly, although the results showed that many factors affected the levels of occupational stress among the respondents sampled, not all of them were significant enough. For example, the study identified the correlation between gender and age to be insignificant in affecting the level of stress.

However, education, years employed, and security levels emerged to have a moderate significance with occupational stress. A negative correlation existed between job stress and job security because most of the respondents polled that the lack of job security brought stress. In sum, the graph below rates the five categories of perceptive indices according to their levels of influence of occupational stress.

Discussion

Throughout the analysis of this paper, perceptions of the dangerousness of the job that correctional officers do emerge as the strongest predictor of stress. However, not all the independent variables showed the same influence on the level of stress. For example, a few demographic factors (age and gender) emerged as having an insignificant correlation with stress levels.

Such findings help to clarify inconsistencies in previous researchers that have tried to use demographic indices to predict the levels of stress among correctional officers. For the few demographic indices used in this paper, the number of years employed (only) emerged to have a moderate correlation with stress. The others had either an insignificant correlation (age and gender) or no correlation at all. This finding affirms the minimal use of demographic variables to predict occupational stress among correction officers.

Nonetheless, the moderate correlation between job tenure and occupational stress emerged as an interesting finding because conventional belief portrays job tenure as a significant correlate of occupational stress. Indeed, several researchers have elevated the importance of job tenure in predicting occupational stress.

For example, Millson (2000) said, “Time on the on the job would reduce stress because increased job experience would be expected to enhance competence and self-confidence” (p. 88). Nonetheless, from the same background, the present study shows that work experience draws a moderate correlation with occupational stress. This finding is consistent with other studies that have shown a correlation between the two variables (Brough & Williams, 2007; Finney & Stergiopoulos, 2013).

An analysis of external factors in the organization shows that only two factors have a strong correlation with occupational stress. One notable finding was the strong belief that correctional institutions should have a greater accountability to the public.

However, the study found the correlation between the public image of correctional facilities and correctional officers had an insignificant correlation with occupational stress. Although people should treat these findings cautiously, the findings still help to demystify anecdotal information surrounding the effects of external organizational factors on organizational stress.

Internal factors emerged as having the most impact on occupational stress. In fact, all the internal indices of occupational stress reported significant correlations. This finding means that all the internal organizational factors contributed to occupational stress. Although this paper diversified the internal organizational factors, their effect on occupational stress only focus on three key areas of analysis – employee advancement, staff management, and organizational duty management.

It is therefore unsurprising to see that most issues affecting employee career development had a significant impact on occupational stress for the correctional officers. In my view, this issue emerged profoundly in the present study because, today, career growth opportunities are important in shaping employee perceptions about their jobs.

Mainly this is because pay increments depend on career growth opportunities. The strong correlation between career advancement issues and occupational stress is consistent with other studies, which have affirmed the same relationship. Indeed, as Stergiopoulos & Cimo (2011) found out, limitations on career development were leading causes of health problems among employees.

The internal organizational factors that affect employee treatment in the organization also showed the same level of correlation because the treatment of employees in the correctional facilities had a profound impact on how officers perceived their jobs.

It is therefore unsurprising that most of the respondents said the quality of supervision, staff recognition, and the general treatment of employees played a huge role in influencing how they perceived their job. These findings support the views of past researchers who have emphasized the importance of considering management support when formulating strategies for reducing occupational stress among employees.

Management of work is also another area of internal organizational control that emerged to have a correlation with occupational stress. This analysis highlighted the importance of understanding different facets of work management, such as communication within the organization, policy orientation, and the empowerment of staff (attributes that affect the management of work schedules). Past studies have also shown that some deficits in these managerial facets have a profound impact on how employees perceive their work.

For example, Hogan & Lambert (2006) had affirmed the influence of employee empowerment and policy orientation on occupational stress. The same studies showed the influence of role conflict and ambiguities in influencing how employees perceive their work (job satisfaction). This analysis is especially relevant for correctional officers because people expect them to observe high levels of discipline and role command (professional discretion) in the execution of their duties.

Most researchers have investigated the influence of role conflicts on the execution of duties by understanding how the same factors affect employee empowerment levels. The same studies have presented the influence of role conflicts and job ambiguities by understanding the relevance of policies and procedures (Millson, 2000). For example, in one study, a respondent claimed the failure to observe rules and procedures could lead to negative outcomes for employees.

Variables concerning the work environment suggested a negative correlation with occupational stress. This was true for most indices including perceptions of personal security and the knowledge of the work. Similarly, the same results were true for the impact of shift work and the danger associated with the jobs of correctional officers.

As explained in this paper, the danger associated with the job reported the highest negative correlation with occupational stress. Given the focus of past studies on the nature of work and occupational stress, I expected that the dangerous nature of the work that correctional officers do would have a negative correlation with occupational stress.

Employees’ understanding of their work and their level of training also showed the same negative correlation, although to a lesser extent. This finding shows that most correctional officers who have not received proper training to undertake their duties have a higher likelihood of experiencing stress. The same outcome is true for correctional officers who do not have a proper knowledge of the jobs. A notable outcome of this analysis is the impact of work shifts because most of the respondents polled that strenuous routines stressed them.

Past studies have compared this fact to the commitment of correctional officers to organizational goals and objectives (Finney & Stergiopoulos, 2013). Their findings support the findings of the present study because they argued that most correctional officers who report low commitment levels of organizational goals experience more stress in the workplace.

An analysis of the influence of attitudinal variables on organizational control showed that correctional officers who were less empathetic in their interactions with inmates were more likely to experience occupational stress. The positive correlation between the punitive attitudes of correctional officers and occupational stress affirms this fact. Although there is a small body of research that has focused on understanding the impact of attitudinal factors on occupational stress, the findings of this paper are congruent with previous findings.

Considering the level of correlation for many of the independent variables highlighted in this paper, conducting the stepwise regression analysis was important for this paper to ascertain the main predictors of occupational stress. The hypothesis of this paper is therefore true because one aspect of personal security emerged as the most reliable predictor of occupational stress.

Indeed, the dangerous nature of the job emerged to have a very strong correlation with occupational stress. Staff empowerment (which came second in this analysis) does not match to this correlation. Although most of the independent variables identified in this paper showed a correlation with occupational stress, the impact of these independent variables on the safety of correctional officers at work is insignificant.

Contributions from the staff empowerment scale to occupational stress levels among the correctional officers show that some feelings of lack of empowerment contribute immensely to work stress among the same group of employees. This analysis is true beyond the perceptions of the dangers associated with the job. The contributions of other variables in this analysis also show that the routine nature of workplace responsibilities and strict work schedules may contribute to high levels of stress among the employees.

Conclusion

After weighing the findings of this study, the importance of work environment variables emerges as the most important influence of occupational stress. Demographic factors have the least effect on occupational stress. This analysis shows that the feelings of personal safety top the list of issues that stress correctional officers.

Stated differently, this analysis shows that personal factors are the most significant factors that cause stress among employees. Comparatively, organizational issues outline secondary concerns of personal stress. Psychologists, policymakers, and other stakeholders should therefore consider the importance of improving the work environment of correctional officers if they want to optimize the output of these professionals.

Stress-reduction strategies should also appeal to these issues because this is the best way they can achieve maximum impact on employees. Stakeholders should therefore regard the personal well-being of correctional officers as an important tenet of our justice system because their role in rehabilitating inmates is as important as the need for the justice system to prosecute offenders.

From this background, the findings of this paper support the research hypothesis – work environment factors contribute the greatest indices of occupational stress. Future research should however explore how well stress management philosophies may integrate environmental solutions to relieve correctional officers of stress. A perfect synchrony of work environment dynamics and psychosocial interventions should suffice.

References

Abdollahi, M. (2002). Understanding police stress research. J Forensic Psychology, 2(2), 1–24.

Armstrong, G., & Griffin, M. (2004). Does the job matter? Comparing correlates of stress among treatment and correctional staff in prisons. J Crim Justice, 32(1), 577–592.

Bourbonnais, R., & Jauvin, N. (2007). Psychosocial work environment, interpersonal violence at work and mental health among correctional officers. Int J Law Psychiatry, 30(1), 355–368.

Brough, P., & Williams, J. (2007). Managing Occupational Stress in a High-Risk Industry: Measuring the Job Demands of Correctional Officers. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34(4), 555-567.

Carlson, J. (2008). Thomas G: Burnout among prison caseworkers and corrections officers. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 43(3), 19–34.

Castle, T. (2008). Satisfied in jail? Exploring the predictors of job satisfaction among jail officers. Crim Justice Rev, 33(1), 48–63.

Castle, T., & Martin, J. (2006). Occupational hazard: predictors of stress among jail correctional officers. Am J Crim Justice, 31(1), 65–80.

Cullen, F., & Link, B. (1985). The social dimensions of correctional officer stress. Justice Quarterly, 2(4), 505–533.

Finn, P. (2000). Addressing Correctional Officer’s Stress: Programs and Strategies. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Justice.

Finney, C., & Stergiopoulos, E. (2013). Organizational stressors associated with job stress and burnout in correctional officers: a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 13(82), 1-13.

Griffin, M. (2007). Gender and stress: a comparative assessment of sources of stress among correctional officers. J Contemporary Crim Justice, 22(1), 4–25.

Hogan, N., & Lambert, E. (2006). The impact of occupational stressors on correctional staff organizational commitment: a preliminary study. J Contemporary Crim Justice, 22(1), 44–62.

Kienan, G., & Malach-Pines, A. (2007). Stress and burnout among prison personnel. Crim Justice Behav, 34(3), 380–398.

Lambert, E., & Hogan, N. (2007). The impact of distributive and procedural justice on correctional staff job stress, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Journal of Criminal Justice, 35(6), 644–656.

Lambert, E., & Hogan, N. (2008). I want to know and I want to be a part of it: the impact of instrumental communication and integration on private prison staff. Journal of Applied Security Research, 3(2), 205–229.

Lambert, E., & Hogan, N. (2010). An exploratory examination of the consequences of burnout in terms of life satisfaction, turnover intent, and absenteeism among private correctional staff. The Prison J, 90(1), 94–114.

Lambert, E., & Paoline, E. (2010). Take this job and shove it: an exploratory study of turnover intent among jail staff. J Crim Justice, 38(1), 139–148.

Lavigne, E., & Bourbonnais, R. (2010). Psychosocial work environment, interpersonal violence at work and psychotropic drug use among correctional officers. Int J Law Psychiatry, 33(1), 122–129.

Millson, W. (2000). Predictors of Work Stress among Correctional Officers. Ottawa, Ontario: Carleton University.

Neveu, J. (2007). Jailed resources: conservation of resources theory as applied to burnout among prison guards. J Organ Behav, 28(1), 21–42.

Paoline, E., & Lambert, E. (2006). A calm and happy keeper of the keys: The impact of ACA views, relations with co-workers, and policy views on the job stress and job satisfaction of correctional staff. The Prison Journal, 86(2), 182–205.

Robinson, D., & Porporino, F. (1997). The influence of educational attainment on the attitudes and job performance of correctional officers. Crime Delinquen, 43(1), 60–77.

Stergiopoulos, E., & Cimo, A. (2011). Interventions to improve work outcomes in work-related PTSD: a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 838-840.

Summerlin, Z., & Oehme, K. (2010). Disparate levels of stress in police and correctional officers: preliminary evidence from a pilot study on domestic violence. J Hum Behav Soc Environ, 20(1), 762–777.

Taxman, F., & Gordon, J. (2009). Do fairness and equity matter? An examination of organizational justice among correctional officers in adult prisons. Crim Justice Behav, 36(7), 695–711.