The development of photography in the mid-nineteenth century marked a definitive transformation in visual representation. It also became a sign of the beginning of the shift toward the visual culture that we know in the 21st century. The advent of photography as an accessible art form and the rise of the amateur photographer represented the main drivers of these developments.

The following essay delves into the history of photography as it developed simultaneously in the United States and Europe, and places special emphasis on the history and theory of nineteenth century photography as it developed during the Victorian era.

Photography gained an avid following in the Victorian culture and in many ways facilitated the intersection between Victorian literature and photography, particularly in the works of popular children’s authors such as Lewis Carroll and J.M. Barrie, and revolutionized the representations of children and the province of childhood in popular Victorian literature such as Alice in Wonderland.

The intersection between the visual and verbal cultures in the 18th century and 19th centuries represents another area wherein photography united the intricate inter-relationships between visual images and texts.

Nineteenth century photography with reference to both the figure of the child and the photographs and photographic practices of Victorian women also exerted a significant impact, as evidenced by the works of such early photographers Julia Margaret Cameron.

This essay intends to place both historical and cultural emphasis on these elements and illuminate some of the supernatural elements that photography brought to bear on popular images, particularly those created during the Spiritualist movement of the mid-nineteenth century.

This essay will also investigate the photographic technique of combination printing and its impact on the art form. As Yacavone observes, “it is the double function of the photograph as both evidence of the real and, at the same time, a starting point for a flight of imagination on the part of its beholder, that foregrounds an engagement with literature” (97).

In addition, the novel presence of the camera in nineteenth century culture transformed the act of looking and affected all major social, aesthetic and philosophical categories at the time. This impact of this transformation can still be felt today in the dominance of photography in news reporting as well as the role of digital photography in visual representation and the visual culture of the Internet and social media.

Photography usurped the pictorial representation of painting at the time, particularly in the realm of portraiture, and revolutionized the relationship that individuals possessed not only with their own images and ways of seeing, but also the relationship with time itself.

As Walter Benjamin observed in his seminal 1936 piece The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, “lithography enabled graphic art to illustrate everyday life, and it began to keep pace with printing. But only a few decades after its invention, lithography was surpassed by photography.

For the first time in the process of pictorial reproduction, photography freed the hand of the most important artistic functions which henceforth devolved only upon the eye looking into a lens. Since the eye perceives more swiftly than the hand can draw, the process of pictorial reproduction was accelerated so enormously that it could keep pace with speech” (Benjamin n.p.).

The essay concludes with a showcasing of a number of nineteenth century photographs that illustrate the wide range of uses, particularly in the realm of portraiture, that photographers of the nineteenth century employed the photographic technology of the time to document.

This section analyzes work from Robert Cornelius, Roger Fenton, Alexander Gardner, and Lewis Carroll to highlight the multiple uses of photography as a literary device as well as a means of documenting historical events such as wars.

Pictorialism

Pictorialism was a name given to a style of photography practiced largely from the mid-nineteenth century through until the outbreak of the Second World War; its popularity spans the years between 1860 and 1940 (Batchen 764; Hermange 5; Patty 32).

Photographs created in the pictorialist style are characterized by an obvious narrative approach to their subject matter; pictorialist photographs therefore appear staged and contain heavy application of genre, mood, soft-focus lighting, and impressionist imagery.

Pictorialism was favoured by a number of nineteenth century artistic movements, including the New York based photography group the Linked Ring and Photo Secessionists (Batchen 764; Patty 32).

Pictorialism is best described as a transitional phase between painting and photography.

The pictorialist photographers were essentially thinking like painters, and despite the fact that they advocated the process of photography as a mode of fine art more so than a scientific advance, the photographs created by proponents of the pictorialist movement more closely resembled painting styles and while the goal of the pictorialists was to legitimize photography as art in its own right, the pictorialists nonetheless attempted to match photography to the existing genres of painting.

Thus, the early art works of the pictorialists tended to mimic the styles and genres recognizable from painting.

In the 1850s, art photographers such as Rejlander and Robinson encouraged the creation of stage-managed images that the photographers had handcrafted into photographic images to resemble the mood and framing of painting (Lewis 11). Robinson maintained that a successful art photograph exhibited as much handcraft and finesse as any other popular art medium, such as painting and sculpture.

Photographers such as Henry Peach Robinson and Oscar Gustav Rejlander used multiple exposures, and developed combination printing, in addition to the staging of their photographic subjects (Scott 35). In the 1858 photograph Fading Away for example, the photographer Henry Peach Robinson photographed the scene using a total of six separate negatives.

Each negative was individually printed and cut out, after which Robinson attached the negative to a solitary background. In the next phase, Robinson reconfigured the joinery and then photographed the collage a second time. The goal of this process was produce a seamless print and guaranteed Robinson’s position as one of the most well known and well used photographers of the era.

Pictorialists such as Rejlander and Robinson eventually lost favour to later photographers such as Peter Henry Emerson, who was determined to develop naturalism in photography. Emerson felt that art photography needed to use the new medium to capture reality, and he strongly promoted the use of realistic photography without artifice or manipulation of any kind.

Thus Emerson’s work used real individuals and avoided the use of actors. Emerson also used soft focus, advocated the idea of the photographic salon, and promoted the use of modern photographic processes at the time, including photogravure and platinum (Lewis 14).

By the end of nineteenth century, advances in photography led to the replacement of the Wet Plate with the Dry Plate Process. Soon after, the amateur photographer began to come to the fore of the art world.

The dry plate process offered the main advantage of being pre-packaged; thus, amateur photographers found it much easier to take photos without the need for cumbersome equipment. Kodak also developed a hand held camera in 1888; this first portable camera was coined the Kodak #1 (Lewis 14).

The Portrait

The appeal of photography historically has always been in its ability to depict reality, seemingly without the influence of humans (Batchen 764; Lewis 11). As Scott explains, the scientific element of photography makes it simultaneously an art form and a representative science.

“Photography is about capturing light reflected off objects. It is, therefore, not a branch of drawing, nor even of art: it is a making manifest of the physics of the world and tells us about the creation of volumes and appearances. The miracle of photography lies not in its iconicity, but in its indexicality” (Scott 35).

In the nineteenth century, photography revolutionized the portrait, as it created the illusion of authenticity. As Scott explains, “what is wanted in portraiture is the portrait, and nothing more; no obvious intrusion, that is, of the personality of the producer; a true portrait, of course, an evocation, true to the spiritual and mental as well as to the physical.

And in that lies the potentiality, the individuality of the photographer; that he can arrange a lighting, choose a pose, elicit an expression, which shall say the whole truth of the sitter, inside and out” (37). Photography allowed the image to stand alone without the obvious input of the human hand or eye, as was the norm in portraiture created by the medium of painting.

For the first time in history, the true human face, unadulterated by artifice or manipulated by colour or texture, became available to the human eye. The true human face suggested “a type of reading and literary interpretation…that is crucially informed by photographic material that invites a factual and biographical approach owing to the photograph’s indexical nature as the real past captured and preserved” (Yacavone 99).

The supremacy of the portrait began with the daguerreotype, a method of photography developed by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, a French inventor, and unveiled publicly in France at the August 19, 1839 meeting of the French Academy of Sciences in Paris invented the daguerreotype process in France (Aldred 305; Patty 32; Scott 35).

Even today, the daguerreotype is considered the quintessential example of the true likeness of a person. As Aldred explains, the daguerreotype “epitomizes the uniqueness of the photographic image…the daguerreotype has no negative to be transformed into a positive photographic image…which is therefore capable of being-and has been-manipulated.

Daguerrotypes are literally the authentic trace of the individual whose physical existence is embedded within the metallic image” (Aldred 305). Photographers on both sides of the Atlantic capitalized on this new French invention.

The main appeal of the daguerreotype was that it could produce a likeness never before seen, the ultimate “truthful likeness…[which spawned] theoretical reflections on the photographic image as a framing and freezing of the real” (Yacavone 101).

The daguerreotype style of photography represents a direct-positive process. The daguerreotype creates an extremely detailed image on a sheet of copper plate and applies a thin coating of silver; the daguerreotype does not use a negative.

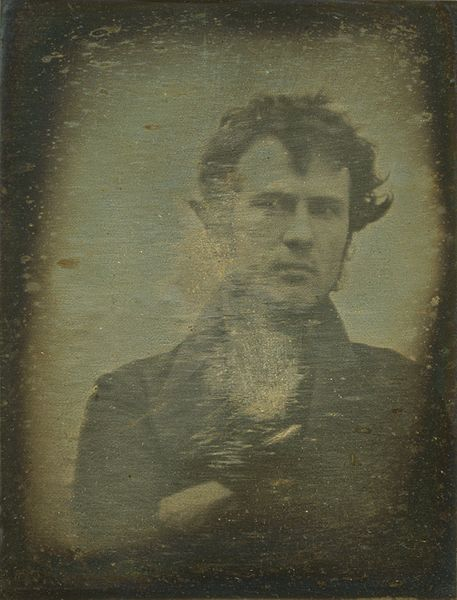

Robert Cornelius

One of the lesser known photographers of the nineteenth century was not actually a photographer, but rather a chemist who stumbled into photography in its early days and is now credited with taking the first photo of a human being, a self portrait, dated 1839 (Patty 32).

Robert Cornelius was born in Philadelphia and lived there from 1809 to 1893 (Patty 32). His livelihood was that of a chemist and a metallurgist. In 1839 he was commissioned to create a silver plate for a photographer to work on a daguerreotype, and this led to his interest in photography.

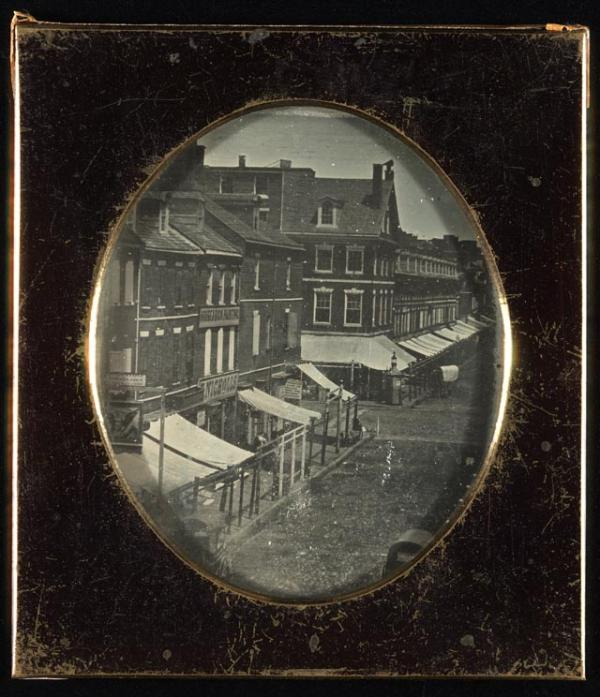

The city of Philadelphia made several other significant contributions to the art of photography, as Patty explains, including “Dr. Paul Beck Goddard of Philadelphia was the first person in the world to obtain an instantaneous picture by heliography, December 1839…

William G. Mason of Philadelphia obtained the first perfect picture in the camera by the aid of artificial light, December 1839…the first portrait studio in America, or more strictly in the world, was opened in Philadelphia, February 1840, by Robert Cornelius, at the northeast corner of Eighth Street and Lodge Alley” (32).

“The majority of photographs assembled by Barthes [do not] correspond in any powerful or interesting way with the mental image evoked by the literary depiction of a character” (Yacavone 101).

However, Robert Cornelius continued to experiment with the daguerreotype process and made several advances to the effect that he could take professional style photographs of human beings and render them full of character, a gift that would eventually inspire a generation of photographers after him. At that point in history, human photography was largely unknown.

Robert Cornelius opened two successful daguerreotype shops in Philadelphia in the late 1830s, which he operated until 1843 (Patty 32). After that time, Robert Cornelius appears to have lost interest in the photography venture and returned to work at his father’s lighting and gas company. As Patty explains, “Cornelius was a scientist and a businessman, not an artist” (32).

Other valuable contributions made to the art of photography by Philadelphians include “the first heliograph ever entered for exhibition was one by Dr. Joseph E. Parker at the tenth exhibition of the Franklin Institute, held in October 1840…the first photo-mechanical reproduction for use with printer’s ink, which combined in its production the daguerreotype, electrotype and a mechanical process…[and] the first successful attempts at interior photography were made by Dr. Paul Beck Goddard, January 1840, at the Academy of Natural Sciences at the southeast corner of Twelfth and Sansom Streets.

The originals are still in existence” (Patty 32).

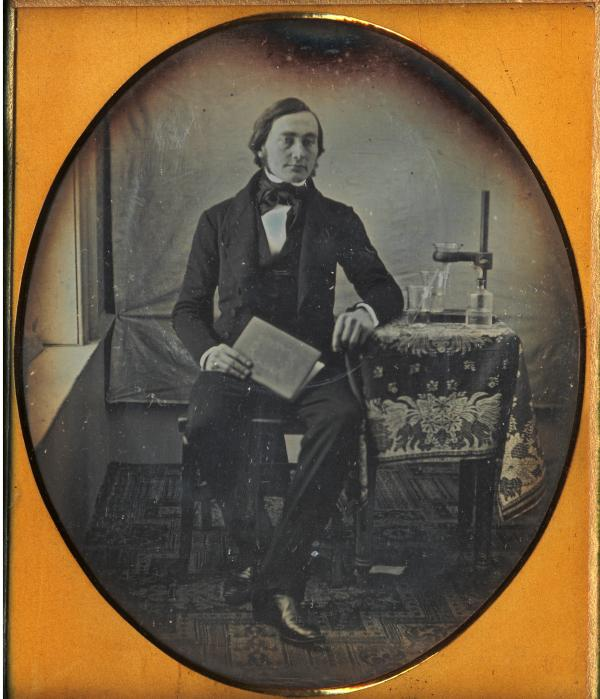

Roland Barthes explained that “the photograph is literally an emanation of the referent” (44). Robert Cornelius’ photographs, though created by a non-artist, nonetheless contain a uniqueness of pose and expression rarely found in other nineteenth century photographs, as evidenced by the portrait of Martin Hans Boye, dated 1841.

The relaxed expression and natural position of the subject’s body countered the stiffness and formality of most other nineteenth century portraits.

“As an emanation, the photographic object therefore retains a tangible trace of the photographic subject. Thus, the photographic record of the past is unique amongst those of all other media because it is founded on a chemical process that makes it possible to recover and print directly the luminous rays emitted by a variously lighted object” (Patty 38).

It is this private, personal connection between the photographic and the photographic subject that separated photography from all other art forms.

Robert Cornelius appears to have discovered a unique style, one that inspired a generation of photographers after him, despite the fact that he eventually gave it up and moved on. As Patty explains, Robert Cornelius’ genius lay in how he posed his subjects, particularly in the self portrait for which he is so well known.

“Even Cornelius’ improved daguerreotype process required that the subject sit perfectly still for several minutes, so it is particularly interesting that he chose such an active pose…the charm of the 1839 portrait lies in its modernity: he stands with an informality and lack of pose that it is shocking to see in pre-1900 photograph.

[Critics have become] inured to the idea of the stiffly posed Civil War and post-Civil War photographs, but Cornelius’ portraits are full of personality. That’s also hard to reconcile with the era” (Patty 38).

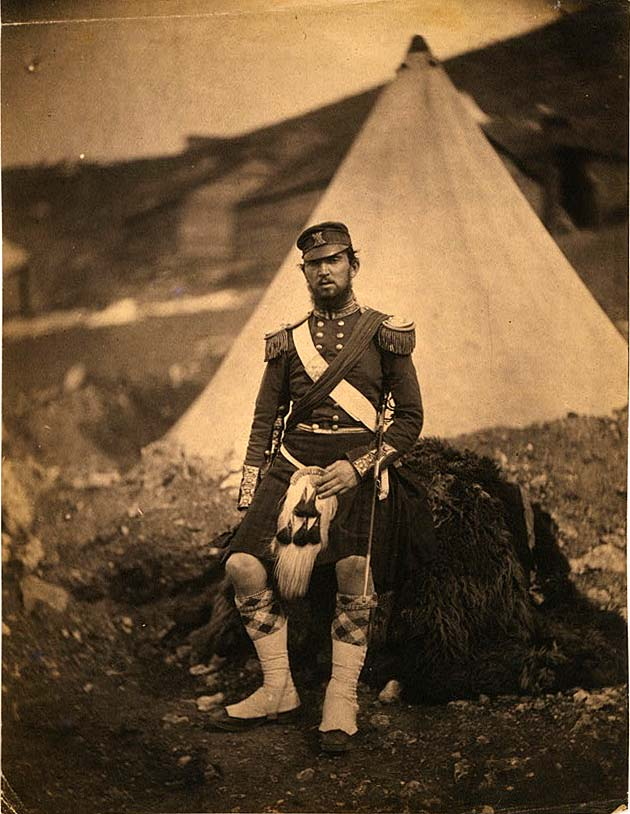

Roger Fenton

Roger Fenton could well be the world’s first war correspondent. Improvements to Daguerre’s process in Fenton’s day, including the use of bromine as an accelerator for the process, “made its universal application possible, and in reality form the basis of the whole photographic structure of today” (Patty 32).

These improvements allowed Roger Fenton to become one of the most famous nineteenth century war photographers. Born in England, Roger Fenton came to the fore as a photographer during the Crimean War between 1853 and 1856.

Roger Fenton became well known after the release of the Crimean War photographs that detail enormous barren wastelands populated by soldiers and horses, as well as informal and revealing portraits of generals and officers, as evidenced by the 1855 photograph of Captain Cuninghame.

As Yacavone explains, “the process of viewing the images themselves, evidences the fact that the imaginary is always already active while viewing photographs, inasmuch as they display a high degree of interpretation, association, and addition that cannot be reduced to the photographic image or to the literary depiction of the photographed person” (Yacavone 102).

Such is the case with Roger Fenton’s photograph of Captain Cuninghame.

In this photograph, Roger Fenton captures the deep fatigue of war; despite his elaborate costume and military stance, Captain Cuninghame’s weariness is palpable in this photograph, and his scraggly beard and heavy eyelids betray the fact that he has not had access to a razor or sleep in a very long while (Patty 32). There is clear ambiguity between the warrior pose and warrior costume and the man himself.

“This ambiguity regarding the illustrative and documentary capacities of photographic documents has provoked recent critics to explore the provisionality of these images and their radical resonances…They manifest the disparity between the catastrophic events of history and the ability of human memory and archival technology to accurately recall them” (Patty 37).

Roger Fenton was born in Lancashire in 1819. Thomas Agnew and Sons, a publishing company from London, commissioned Roger Fenton to take photographs of the English army’s activities during the war that took place on the Crimean Peninsula (Patty 32).

Roger Fenton was hired by and large to “sell” the Crimean War to the British public. While Thomas Agnew and Sons held the commercial interest in the results of Roger Fenton’s travels, there was also national interest from the monarchy top improve the image of the war.

While the images that Roger Fenton captured on the Crimean Peninsula are arresting, they are “by no means neutral; rather, they represent a contemporary agenda” (Patty 32).

The success of Roger Fenton during the Crimean War can be attributed to the photographers foresight and ability to plan and prepare effectively. The journey to the Crimean Peninsula was a tough one, and many other British photographers had lost everything, even their negatives, through the weather, capsizing at sea, wind damage, or a lack of proper fixation (Patty 32).

Roger Renton went to the front in a “photographic caravan [that] included 5 cameras, 700 glass plates…in three formats…lab Materials, and a bed. Nineteenth century war photography was not for the feeble.

Fenton, who practiced the Wet Collodion process, had to travel in foreign terrain with an entire darkroom set-up and several large, bulky cameras” (Patty 32). Roger Fenton’s hardiness and ability to tell a story with a lens allowed audiences in Britain access to the front in an unprecedented manner.

When Roger Fenton left for the Crimean Peninsula, the public opinion regarding the war in Britain was ambivalent; the public knew that some of the English soldiers were dying from starvation and that the living conditions were abysmal. The Queen at the time, Queen Victoria encouraged Roger Fenton to capture “tasteful views of picturesque scenes,” rather than images of violent skirmishes and bloody war scenes (Patty 32).

American Civil War Photographs

The American Civil War became one of the world’s first heavily documented wars, on account of the development of photography. When war was declared in 1861, an American portrait photographer named Matthew Brady recognized the opportunity to immortalize his work through the act of documenting history (Holzer 44).

Literature at that time was extremely pro-war and tended to glorify the pursuit of war as manly, brave, and an act that constituted the duty of free men (Holzer 49) Matthew Brady successfully placed professional photographers in the field of battle, much like the U.S. army imbeds war correspondents in the wars of today.

Some of the famous photographers that Brady amassed to work on his war documentation project included Timothy O’ Sullivan, Alexander Gardner, George N. Bernard, and George Cook (Holzer 44).

Matthew Brady and this team of photographers shot over 8,000 negatives (Holzer 44). Most of these negatives now reside in the National Archives as part of the Brady Civil War Collection (Holzer 45).

Matthew Brady’s photographers were on the scene at many of the key battles of the American Civil War, including Gettysburg, Antietem, and Petersburg, although many of the photographs depict death scenes and dead bodies more so than battle scenes.

Some critics have maintained that the pro war nineteenth century aesthetic precluded the photographers from capturing the horrors of battle more so than the exposure time (Holzer 45). Many critics and historians alike have also claimed that the bulk of Matthew Brady’s Civil War photographs were pictorialist in nature – that is, staged.

As Holzer explains “exposure time still prohibited photographers from successfully capturing warfare. [However] historians have speculated that some of the Brady Civil War pictures were, in fact, staged.

Like the Gardner photograph pictured above and the O’ Sullivan photograph pictured below, dead bodies were sometimes moved and repositioned in order to capture a more compelling image. Debates about the difference between psychological and physical truth have stirred many Civil War photo enthusiasts” (47).

George Houghton

George Houghton was a contemporary of Brady and Gardner whose work depicted the mundanity of war – waiting, especially, as evidenced by his most famous portrait of a Berdan’s Sharpshooter named California Joe. The sniper’s real name was Truman Head.

In this photograph, California Joe watches for Rebels, in what represents not only Houghton’s most famous picture, but also the tedium that befell many soldiers during the Civil War (Holzer 2012).

Alexander Gardner

Alexander Gardner is best known as a photographer who worked during the American Civil War to bring the images of battle to the public. His work contains a disturbing contradiction to the literature of the time which tended to glorify the war.

In response to what he had seen and read about the Civil War, Alexander Gardner wrote, “slowly over the misty fields of Gettysburg – as all reluctant to expose their ghastly horrors to the light – came the sunless mourn, after the retreat by Lee’s broken army.

Through the shadowy vapors it was, indeed, a harvest of death that was presented… such a picture contains a useful moral: it shows the blank horror and reality of war, in opposition to its pageantry. Here are the dreadful details! Let them aid in preventing such another calamity falling upon the nation!” (Holzer 46).

The reality of the war and the unwillingness of the literature of the time to report the war as it was frustrated Gardner so much that in 1866 he published Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of The War, and published many of today’s most famous American Civil War photographs.

Alexander Gardner was also one of the first war photographers, and he accompanied many of his photographs with texts that detailed the time and situation that the photograph depicted. Alexander Gardner’s texts and photographs speak to the issue of psychological truth in photographs and contributed significantly to the later visual culture of war correspondents that popularized later wars such as World War II and the Vietnam War.

Lewis Carroll

Author Lewis Carroll is best known as a children’s author; however, he was also a skilled photographer in his own right. Lewis Carroll especially understood the power of the portrait to infuse a photograph with the essence or soul of an individual. Lewis Carroll’s work also favoured the pictorialist style of portraiture, as evidenced by one of his most famous photographs, The Beggar Maid (Susina 33).

As Yacavone explains, “the photograph is clearly linked to the viewer’s personal life-experience in relation to the depicted person…the imaginary is the hinge, as it were, between the photograph and the literary work, or, more specifically, between the real-life person and the character” (101).

In Lewis Carroll’s photographs of children, particularly those that include Alice Liddell, we see the relationship between the writer and his muse depicted.

In The Beggar Maid, Lewis Carroll’s child muse, Alice Liddell, dresses up in a torn outfit made of rags and poses in her bare feet against a brick wall. One hand rests on her hip and the other she cups in front of her in the classic gesture of a panhandler. The fascinating element of this photograph remains Alice Liddell’s expression; she is at once defiant, feisty, entitled, vulnerable, bored, curious, naughty, and mischievous.

Lewis Carroll’s photography of children fuses an appreciation for the world of children, particularly their imagination, with an uncanny ability to capture the air and essence of an individual child, as evidenced particularly in the body of work that Lewis Carroll created using Alice Liddell as a model and muse (Leal 11; Susina 33).

In these photographs Lewis Carroll combines the magic of the child’s imaginative world with the scientific accuracy of the photographic portrait.

In the nineteenth century, the development of the art of photography transformed not only the ability of portrait artists to capture their subjects; it also facilitated the intersection between Victorian literature and photography, and created some of the most enchanting combinations of literature and photography, particularly in the work of Lewis Carroll.

The development of photography in the nineteenth century also began the fundamental shift from painting as the main medium of representation, and facilitated the shift to the visual culture of the late 20th century and 21st century.

Works Cited

Aldred, Nannette. “The Portrait in Photography.” The British Journal of Aesthetics 33.3 (1993): 305-306. Print.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida. London: Hill and Wang, 1980. Print.

Batchen, Geoffrey. “Light and Dark: The Daguerreotype And Art History.” The Art Bulletin 86.4 (2004): 764-776. Print.

Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Marxist Literary Criticism Philosophy Archive. Web.

Benjamin, Walter. “A Short History of Photography”, in Alan Trachtenberg (ed.), Classic Essays on Photography. New Haven: Leete’s Island Books, 1980. Print.

Cornelius, Robert. Martin Hans Boye, 1841. Web.

Cornelius, Robert. Self Portrait, 1839. Web.

Cornelius, Robert. Street Scene of Eighth and Market Streets, Philadelphia, Sixth-plate daguerreotype, May 1840. Web.

Hermange, Emmanuel. “Aspects and Uses Of Ekphrasis In Relation To Photography, 1816-186O.” Journal of European Studies 30.1 (2000): 5. Print.

Holzer, Harold. “War around the Edges.” Civil War Times 51.1 (2012): 44-58. Print.

Leal, Amy. “Lewis Carroll’s Little Girls.” The Chronicle of Higher Education 54.10 (2007):11-15. Print.

Lewis, Robert. “Photographing the California Gold Rush: Robert Lewis looks at the historical evidence contained within the daguerreotypes taken during the 1849 Gold Rush.” History Today 52.3 (2002): 11-23. Print.

Patti, Tony. “The Philadelphia influence.” PSA Journal 61.7 (1995): 32. Print.

Scott, Clive. “Frederick Evans: Photography as Mediation.” Journal of European Studies 30.1 (2000): 35. Print.

Susina, Jan. The Place of Lewis Carroll in Children’s Literature. New York: Taylor and Francis, 2010. Print.

Yacavone, Kathrin. “Reading Through Photography: Roland Barthes’s Last Seminar ‘Proust Et La Photographie’.” French Forum 34.1 (2009): 97-112. Print.