Executive Summary

Brexit has attracted heated debate in the UK and the entire globe. The protagonists and antagonists of this phenomenon seem not to agree on how it is handled from political and policy perspectives. The debate has divided the UK population as evidenced by an almost equal vote supporting and rejecting Brexit. Economics and other professionals have performed a series of scientific studies to examine the quantifiable impacts of Brexit on the general economy. This research study has related short- and long-term effects of Brexit on the trade sector in the UK.

Through quantitative research design, the researcher used secondary data collected from reputable sources to study the performance of trade indicators from the year 1980 to 2022, with a special focus on the period between 2015 and 2022. The findings indicated that Brexit has not significantly affected trade since the slight plunge in 2015 through to 2016 was associated with the normal market reaction. Specifically, the trade parameters are indicating a positive and optimistic growth trend as suggested in the forecast. To optimize trade during and after Brexit, the government should expedite the process and create more dynamic policies to expand the import and export markets. This will cushion the trade sector from prolonger speculative market reaction forces.

Introduction

Trade and political blocs have been in existence since the establishment of international trade. The purpose of such blocs, historically, has been the establishment of trade standards, elimination of border restrictions, introduction of common quality, transportation, and inspection regulations, freedom of movement of goods and services, and the adoption of unified external political and economic positions about other countries (Oliver 2016). The ultimate goals of trade and political blocs are to ensure the safety and prosperity of its members, benefits from free trade, a stronger united standing in the international arena, and a collective response against all and any external threats. The first economic bloc in our modern understanding of the term appeared in 1834 under the name of GCU (German Customs Union) (Shuster 2016).

It was then followed by many other regional, continental, and world-scaling organizations. Some of the most famous trade blocs include the WTO (World Trade Organization), the EU (European Union), ASEAN (Association of South-eastern Asian Nations), NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) (Buddi 2014). The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON) implemented by communist countries, such as the USSR and its satellite states, before dissolution in 1991, was also a form of a trade bloc (Smetana 2016). As a rule, the majority of these blocs were founded by powerful political and economic entities with smaller nations joining in through the virtue of falling into the newly found bloc’s sphere of influence. Because of this, history records very few instances of countries voluntarily leaving trade and political blocs that usually did so only after the dissolution of the organization or the weakening of the founding states.

The participation in economic blocs has its downsides, however. Some of the most glaring issues in bloc economy are losses of sovereignty over certain economic and political matters and economic concessions associated with local markets being opened to multinational corporations, which would, in turn, hurt local businesses and weaker economies, interdependence issues generated from deep involvement with the system, migration issues, etcetera (Gisondi 2017). Unless the initial conditions of joining have been unfavorable or the bloc is a sinking ship, countries tend to retain their membership rather than deal with the issues born of severing strong economic and political ties with other nations.

The European Union (EU) is a modern politico-economic bloc, which existed since 1951 when the Treaty of Paris founded its progenitor, the ECSC (European Coal and Steel Community), which was then followed by the European Economic Community (EEC), founded after the Rome Treaty of 1957 (Tucker 2017). The union’s most current iteration is based on the Lisbon accords of 2007, which included its newest members and established the EU as a legal entity with a legal personality. Its’ largest and most economically and politically powerful members until 2016 included France, Germany, and the UK, which, together, constituted the majority of EU’s military, political, and economic power (Shuster 2016).

From a union born of mutual historical, political, and economic ties, the EU became an overarching state-like figure with an overarching government in the form of the European Council and the European Parliament (Raut 2017). Its power over the individual member states has been increasing as well. As it stands, it is an economic and political powerhouse considered by many political and economic academics to be an emerging superpower. Its population is well over 510,000,000 people, it has the second-largest GDP of 21.7 trillion USD, and it is one of the most influential entities in the international economic and political arena, right next to China and the USA (Armstrong & Portes 2016). The referendum for leaving the EU, conducted in the UK in 2016, was a very unusual political event.

The dissent against the collective nature of the EU as well as various local economic issues have been piling up since the economic crisis of 2009. They were followed by the Greek debt crisis, the Spanish debt crisis, the mass migration problem, and the general division between the “Rich North” and “Poor South.” This was the first time in the history of the EU that one of the founding members of the organization chose to leave (Raut 2017). The analysis of various political and socio-economic reasons for the so-called Brexit, according to Sampson (2016) included long-term deindustrialization, issues with immigration, cultural and historical dementia, nationalism, and inefficient leadership from pro-EU politicians and the overarching macro-managers from the European Council (Armstrong & Portes 2016). The ongoing departure of the UK from the politico-economic alliance has bolstered separatist movements and euro-skepticism across Europe and outside of its borders, significantly damaging the organization’s image in the international arena.

Analyzing and elaborating on the underlying causes of Brexit is not the primary topic of this dissertation. The people have spoken, and the UK now has to face the short-term and long-term consequences of its decision. Severing ties with a trade bloc has never been done without great consequences of the negative sort. However, since Brexit was motivated by an ongoing internal crisis within the EU, the reclamation of political and economic freedom offers various advantages that the UK can capitalize on to mitigate the effect of its membership in the trade bloc. The majority of analysts and researchers highlight several key areas that would be affected the most, which are as follows:

Immigration: The UK would be able to implement border and migration controls to curb the flow of migrants from the Middle East as well as Eastern-European countries, which have been offsetting the country’s economy by artificially decreasing wages, working illegally, and antagonizing the local population by allegedly stealing jobs and increasing poverty (Armstrong & Portes 2016). As it stands, the issues about a possible loss of a potent source of a qualified workforce to benefit the UK industrial sector remain understudied.

Economy: Some of the economic issues with leaving the EU include a massive loss of exports as well as imports. Historically, the UK benefited from joining the EU, which opened the bloc’s markets to its products. Also, the UK would be denied direct access to the EU’s investment market and the EU bank, which the country holds a large margin of finances (Sampson 2017). Lastly, the loss of licenses within the UK by all foreign companies and operators will present a substantial problem.

Foreign Investments: The set of opportunities and threats is very diverse in this segment due to the fluid and unstable nature of investment markets. On the one hand, the UK will be able to conduct its policy to make the country more attractive to foreign investors. At the same time, the lack of stability and affiliation with the EU could make some cautious about investing in the country’s economy. The attractiveness of the UK for the investors would depend on their performance in comparison to the EU, which is undergoing one economic crisis after another (Raut 2017).

Political Opportunities: Although the UK reclaims its sovereignty overall internal and external political matters, the capabilities of the UK to influence the EU or any other superpower in the international arena are likely to suffer a drop (Armstrong & Portes 2016). Also, Brexit itself is likely to cause a divide within the country based on whether it was a good idea or not, as short-term losses are likely to supplant the euphoria of the referendum (García-Herrero & Xu 2016a).

Literature Review

Introduction

This section of the proposed research study reviews different aspects of economic challenges and benefits associated with Brexit. This section examines the theoretical and empirical literature that is related to the topic, An Examination of the Challenges and Opportunities for the UK Post-Brexit. The literature review concentrates on secondary data from the political and institutional reports, mass media articles, journal articles, and public forum blogs. Since the research topic is specific, this section will present a focused information presentation aligned to the objective of establishing the positive and negative impacts of Brexit on the UK economy. The chapter will conclude by related the empirical and theoretical data to the research question to establish the literature gap to be filled by this report.

Challenges and Opportunities from the Immigration Perspective

The post-Brexit is laden with a series of opportunities and challenges as confirmed by a various study on its impact on immigration. According to Gisondi (2017), the current migration activity within the European Union is an indication of deregulated policy, especially in Greece thereby expanding the challenge of illegal immigrants across Europe. The main challenge under the current arrangement is the unregulated immigration among member states of the EU (Bloom, Draca & Reenen 2016). For instance, illegal and excessive immigration movement from some states such as Greece is often directed towards the UK and other stronger states (Smetana 2016). Unfortunately, the UK has become a victim of this unregulated migration as immigrants from other parts of Europe settle in regions they perceive as better than their home country (Tucker 2017). Over the years, the UK has been unable to effectively deal with this challenge due to the EU pact that removes the barriers to cross border movement among member states (Sherif 2018).

Proponents of controlled migration in the UK have argued that the post-Brexit is an opportunity for addressing the immigration challenge since the United Kingdom will have control of its migration laws (Bloom, Draca & Reenen 2016). For instance, Buddi (2017, p. 9) argued that “many voters were motivated by the proposition of immigration control after the separation from the EU”. Before Brexit, there was uncontrolled and often illegal migration into the UK and the EU pact could not allow the United Kingdom to effectively intervene since it would go against the union’s migration policy (Smetana 2016). After Brexit, the UK will not only be able to initiate immigration policies with its boarders but also regulate the processes and channels for controlling movements for its citizens and neighbors. Buddy (2017, p. 17) noted that “voters in favor of the decision have nationalist sentiments and are moved by a utilitarian approach which reflects that they want entry barriers for immigrants in the UK”.

The proposed barriers will result in increased job opportunities and reduced pressure on public goods. As a result, the UK government will be in a position to gain full control of the resources and desired structure of the population. This position is supported by Tucker (2017) who has discussed immigration control as an opportunity for regulating costs in the UK. Through a detailed study on the perception of the common UK citizens on the flow of immigrants, Tucker (2017) established that the general population thinks that immigrants contribute to the rising cost of running the nation. This means that the common citizen is convinced that tighter and regulated immigration laws would be reduced if the UK government’s post-Brexit migration laws are implemented (Bloom, Draca & Reenen 2016). Therefore, the utilitarian perception of reduced costs is an opportunity for diversion of the expenditure used to maintain immigrants towards provision and servicing of public goods such as the transport infrastructure and healthcare facilities (Armstrong & Portes 2016).

Armstrong and Portes (2016) argue that the post-Brexit environment will provide an opportunity for establishing and regularising a control system for effective internal management of government budgets. However, this opportunity comes with negative impacts on the labor force, especially for the unskilled sectors. Raut (2017) explains that more than 10% of the UK labor force is represented by working immigrants. These immigrants provide affordable labor as a factor of production and are not expensive to maintain for the low profit and high production firms in the United Kingdom (Armstrong & Portes 2016). When the post-Brexit immigration laws are made unfriendly to the immigrants, the UK workforce is expected to shrink by up to 10% as a result of reduced cheap labor (Full report-graduates in the UK labor market 2013 2014). Consequently, Bloom (2014) suggests that the local industries will have to absorb the increasing cost of human capital since the locals are not willing to provide labor at a very low cost. Moreover, the level of innovation might plunge since the workforce will lose different skill sets from other regions (Bloom, Draca & Reenen 2016).

The impact of post-Brexit immigration laws on the UK labor market is predicted to have a long term effect on the factors of production and reduced the GDP, especially when the government does not create counter policies for balancing the lost skills (Armstrong & Portes 2016). At the same, the utilitarian members of the society draw from the labor unions, and other private organizations have presented a counterargument that immigrant workers are a loss of native wages.

However, this argument is driven by a populist agenda since there is no previous scientific research that has confirmed these fears (Bloom 2014). Most of the past research studies have confirmed that most immigrant positions are surplus labor needs that cannot be met by the local market (Bloom, Draca & Reenen 2016) and (Sampson 2016). For instance, research by Sampson (2016) confirmed that working immigrants are an important contributor to the multiplication of the UK GDP in the formal and informal sectors since they reduce the cost of labor, thus, increased output. In the context of the proposed research study, the researcher could not locate any literature proposing the option of solving the loss of labor as a factor of production through an immigration-driven policy or pro-Brexit movements.

Challenges and Opportunities from the Economic Perspective

The UK is generally a mixed market economy regulated by the forces of demand and supply in addition to government regulations. The main characteristic of a mixed market economy is that resources are privately and publically owned. Therefore, the decision on how to allocate the resources is made by the individuals and intervention of the government (Armstrong & Portes 2016). Further, there is freedom of choice to produce, sell, and purchase. The only constraints that the private owners face are capital availability and the prevailing prices in the market, unlike publically owned ventures. Another feature of this mixed market is that the force of competition keeps prices low.

The competition also ensures that products and services are manufactured efficiently. Therefore, a mixed market economy relies on an efficient market for trade to happen (How important is the European Union to the UK 2015). Further, properties are often held by both public and private owners. In a mixed economy, there are some state-owned undertakings and economic planning. Another role of the government in such an economy is giving guidelines for the allocation of resources that exists naturally (Bloom, Draca & Reenen 2016). In the case of the UK, the Brexit debate is expected to have a direct impact on private and public ventures due to government participation in trade policy formulation and implementation.

The persistent global financial crisis of 2008-2009 affected the EU economies extensively. Among the most affected economies were the UK, Greece, and Germany, and Spain. Since then, the United Kingdom has managed to maintain a relatively steady economy, which is largely stagnant on a single digit of growth. Despite this relatively low growth rate, trade in the UK is the highest in comparison to other EU member states (How important is the European Union to UK 2015). At present, the government data indicate that the EU market absorbs 46% of UK exports (Bloom, Draca & Reenen 2016). This is an indication that the UK stands to lose a sizable market in the short term in the post-Brexit economic market. At present, the member states of the UK are instrumental in absorbing almost half of the UK exports.

Following Brexit, it will be difficult for the UK to benefit from the EU trade agreements to sell its products to the neighbors (Syal 2016). Specifically, the post-Brexit economic environment will have to be organized into new trade policies with the current trade partners (Bloom, Draca & Reenen 2016). Although the UK will establish a common trading ground through different policies, the process might take a long time and have diverse effects in the short term export trade (How important is the European Union to UK 2015). The trade situation within the UK experienced a positive growth following its decision to be part of the European Union (Bloom, Draca & Reenen 2016). At present, the trade relationship with other member states of the EU is stable and laden with mutually beneficial economic policies (Shuster 2016). The departure from the EU will require fresh negotiations based on focused terms and conditions that will require a lot of time to reinstate the current benefits (Armstrong & Portes 2016).

As noted by Bloom (2014) the economic impacts of Brexit will have similar or even higher challenges on other EU member states trading with the UK. Batsaikhan, Kalchik, and Schoenmaker (2017, p. 24) argue that “London has been the hub of financial activity for a long period and the exit of UK from European Union will mean that 27 partnering countries of EU will lose the license to operate in the UK”. Unfortunately, a shift in the financial and trading hub from the UK to another EU state would have diverse negative impacts on UK’s competitiveness and might force the local firms to suddenly readjust (Bloom, Draca & Reenen 2016). Although the readjustment is short term, its effect could result in reduced GDP by up to 5% (How important is the European Union to the UK 2015). Trommer (2017) notes that UK must establish a new trade defense away for the EU for its local market in addition to signing agreements with international partners to survive the interruption of the trading system in the EU.

The post-Brexit is also laden with several economic opportunities for the UK to initiate modern, effective, and independent trade agreements that are flexible to the needs of the local economy (Sampson 2016). For instance, the government report suggests that Brexit will give the UK an upper hand in negotiating and participating in the global market as an equal partner, rather than a member of the negotiating unit (Mathews 2016). The “UK banks hold about £20 trillion of gross national derivatives with EU, which is about one-fifth of the entire EU banks holding” (How important is the European Union to UK 2015, p. 4). Therefore, a Brexit is an opportunity for further market expansion and renegotiation with the EU as a partner with a fifth of the national derivatives (Boulanger & Philippidis 2015).

This position is supported by research carried by Mathews (2016) on the economic benefits of Brexit to the UK economy. Through a comparative review of the UK exports and imports with those of other member states, the findings revealed that the United Kingdom is poised to gain through an expanding economy since it exports more than it imports into the local market. Moreover, the UK economy is the strongest and holds nearly 25% of the EU GDP (How important is the European Union to the UK 2015). In the EU bloc, the UK has the largest economy as compared to other member states. Over the years, the UK has experienced the highest level of annual economic growth and its economy is nearly double that of weaker partners (Bloom 2014). Therefore, in the event of an exit, the UK’s economy is poised to expand further from better and independently negotiated trade deals (Armstrong & Portes 2016). For instance, the UK might become an equal trading partner of the EU while pursuing other economic expansion policies (Boulanger & Philippidis 2015). The challenges and opportunities highlighted in the literature review present a significant viewpoint of the economic situation at present and in the post-Brexit era.

Challenges and Opportunities from the Foreign Investment Perspective

Brexit means that UK has to suspend the EU trade policies and move on as an independent economy. The transition will be characterized by dissociation with all regional investment agreements and replacing them with local trade decisions and policies (How important is the European Union to UK 2015). Although the UK will eventually create and stabilize the policies with new trade partners, the process is very tedious and might take up to a decade or even more (García-Herrero & Xu 2016a). This means that UK will have to renegotiate the trade policies with the EU and agree to the new terms to avoid sudden disruption of trade, especially in the financial and export/import agreements (Dobiles 2017). Opportunities for expanded trade with other global economic powerhouses such as China, Russia, the US, and Indian are unlimited following Brexit. Specifically, the UK will be free to create and manage independent trade policies to the government the international partnerships, unlike the current state where it has to pass through the EU (Armstrong & Portes 2016).

The possibility of open and flexible internal trade deals will elevate the UK economy further and present opportunities for double-digit economic growth as a result of expanded export and import trade (García-Herrero & Xu 2016b). Since the UK presently acts as the trade facilitator between China and the EU, the exit will reduce the trade deficit for other members of the European Union while increasing surplus for the United Kingdom (Geddes 2013). Gracia-Herrero and Xu (2016a) note that the pre-exit foreign investment from China in the UK from 2010-2015 reached EUR15.16 billion. Therefore, losing membership would have a ripple down effect on the short term foreign investment strength for the UK economy due to adjustments and withdrawal of the neighboring investments from London and other major cities (Boulanger & Philippidis 2015). However, the effect is only short term since trade negotiation in the post-Brexit will only benefit the UK economy unlike the current EU community model (Bloom 2014).

Proponents of Brexit have presented their arguments in support of the separation from the EU using the sectoral value-added effect theoretical model, especially in the event of soft separation. Egger et al. (2015) note that soft Brexit will allow the UK to join the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) to eliminating the possible non-tariff barriers such as border controls, customer checks, and product market regulations to reduce the cost of trade (How important is the European Union to UK 2015). However, the event of a hard Brexit would expand the non-tariff barriers and bring mixed results (Boulanger & Philippidis 2015). Another theoretical model that explains the effects of Brexit on foreign investment and general trade is the trade static framework. Egger et al. (2015) apply this trade model to correlate foreign investment to trade policies. The findings suggest real changes under different policies against potential barriers and trade volumes. Other studies have established that FDI is beneficial to productivity (Boulanger & Philippidis 2015).

This means that “a gravity model of FDI between 34 OECD countries and find that Brexit would likely lead to a fall in FDI to the United Kingdom by over a fifth” (Yu et al. 2017, p. 43). Irwin (2015) suggests that such a sudden fall has the effect of reducing GDP by 3.4%. Since financial services constitute more than 45% of the FDI stock in the UK, foreign investment will be vulnerable in the post-Brexit (Boulanger & Philippidis 2015). For instance, the withdraw of Swiss banks from the UK would reduce the FDIs enjoyed under the current arrangement with the EU. Thompson, Espinoza, and Mance (2017, par. 9) note that “some countries believe that the decision of Brexit will bring long-term prosperity for the UK and make it ideal for investment”. For instance, Qatar has already committed to a £5bn foreign investment in the UK after Brexit (Thompson, Espinoza & Mance 2017).

However, the main challenge is the possibility of the UK attract more FDI through this international trade than it does now under the EU. The potential revaluation of trade might also have an impact on several multinational companies doing business in the UK. For example, the current lowering may be instrumental to the US-based multinationals to strategically develop an improved trade agreement with their partners in the UK. This trend could be associated with the potential lowering of transactional costs (Boulanger & Philippidis 2015). This means that the US multinationals and other partners will experience expanded returns as part of the cost reduction benefits. However, multinational companies with dominant foreign operations in the Euros may not experience the cost-benefit from interest parity (Thompson, Espinoza & Mance 2017). The interest rate parity condition is a nonarbitrage condition that represents the equilibrium state at the point in which investors in that market will show indifference to the rates of interest that are available.

Challenges and Opportunities from the Political and Governance Perspective

Several factors should be taken into account before considering a trade in the UK, especially in the event of a successful Brexit. The most significant “items to take into consideration are the tough business environment, political, and economic uncertainties” (How important is the European Union to UK 2015, p.6) since the vote was split into almost a half. These factors are significant in determining the international company’s ability to strategically enter the expansive UK market and efficiently do business. Moreover, they control profit generation since the UK market is multifaceted (Boulanger & Philippidis 2015). Public protest and demonstrations have become an apparent social risk that the UK faces in the Brexit debate (García-Herrero & Xu 2016a). For instance, the unending social unrests witnessed in the recent past could be attributed to increasing income disparity, inflation, rising unemployment, reducing public security, political divisions, and reduced development (Bloom, Draca & Reenen 2016).

Most of these issues could be resolved by the government of the day. Moreover, the UK capital risk is relatively high. This can be attributed to the high level of local debt, which has grown tremendously over the years. For example, “in 2013, local debt was about 130% of GDP. In comparison, the debt was high at 145% of GDP in the year 2016” (Thompson, Espinoza & Mance 2017, p. 25). Most of these debts are accrued by state corporations. Notwithstanding, the shadow banking sector in the UK has substantially reduced the country’s ability to effectively evaluate its debt levels, especially in the private sector. Also, the rising magnitude of debt defaulters in the bond market has made the capital risk to growth further (García-Herrero & Xu 2016a). At present, “slightly more than ten companies have defaulted since the beginning of the year 2017. If the trend persists, then it can distort the capital market because banks will be exposed to the risk of declining asset quality” (How important is the European Union to UK 2015, par. 13).

The post-Brexit political environment might experience many challenges about the global power alliances and the dynamic international political terrain (Rojas-Romagosa 2016). UK stands to lose important allies who are currently members of the EU. Oliver (2016) noted that even though a successful Brexit is likely to attract more economic opportunities, surviving the negative impact of the voter referendum in an already fragile nationhood fabric might prove to be a challenge. Specifically, the vote margin for proponents and opponents of Brexit was less than 2% (Thompson, Espinoza & Mance 2017). This means that the political class will have to convince 48% of the votes to embrace the post-Brexit environment. This means that the UK is facing an imminent backlash from the opponents of Brexit in the event of prolonged challenges (How important is the European Union to UK 2015).

Oliver (2016, p. 692) also noted that “Brexit will render geopolitical challenges for UK such that Germany will become an important economically strong country in the European Union and political ties with Germany will become a cause of resentment or problems for the UK”. Also, the proposed stronger immigration policies in the post-Brexit might escalate tension between the UK and its neighbors (Boulanger & Philippidis 2015). UK has to come up with strategies for rebuilding its political alliance in the event of a hard Brexit or delayed renegotiation with the EU for a more beneficial union. The process of building new strategic political alliances might take a lot of time since different regions have unique needs. However, proponents of Brexit are optimistic that substantial changes for each cluster of wages and benefits are negligible within the ‘employer’s nonprofit curve’. The same relationship functions in the Wage-Fringe optimum. Tax advantages to employers, the scale of economies, and efficiency are a major factor that led to the growth of fringe benefits, thus, improved trade. Therefore, as fringe benefits increase, the worker’s utility will increase in the same ratio.

Stock Return and Financial Performance of a Company

The stated value of a common stock is the value that is given to common stock in the balance sheet of a company. This is the value that is given to common stock in the balance sheet. The value does not embody the market value and it is only used for accounting purposes. The value is arrived at through the division of the value of the common stock by the total number of issued stock (Boulanger & Philippidis 2015). It does not represent the market value and it is only used for accounting purposes. The value is arrived at through the division of common stock total value by the total number of the issued stock. Dividends paid are often stated on a per-share basis or the total amount that is paid at the end of a financial year. The dividend rate can be calculated using either of the two values (Rojas-Romagosa 2016). In this case, the total amount paid is provided. Dividends in arrears are those that have been declared by an entity and they have not been paid. The net income that is generated at the end of a financial year can either be paid out as a dividend or retained by a company (Thompson, Espinoza & Mance 2017).

If a company pays dividends, then the value is deducted from the retained earnings balance. According to the cumulative dividend feature, preferred stockholders must be paid both current-year dividends and any dividends in arrears before dividends to common shareholders are paid (García-Herrero & Xu 2016a). The calculations of retained earnings balance presented in the attached excel file are based on the assumptions that the dividends in arrears were declared and that there are no retained earnings restrictions (Bloom, Draca & Reenen 2016). The earnings per share ratio (EPS) is a significant indicator of the profitability of a company.

The value of EPS is arrived at through the division of net earnings that is attributed to common stockholders by the outstanding shares. It shows the amount of profit that is allocated to each share (Egger et al. 2015). A high value is often preferred because it signifies that a company is profitable. On the other hand, the par value of preferred stock is arrived at through the division of the total value of the preferred stock by the number of stock issued (Gisondi 2017). Par value is similar to the face value of a stock. About the UK trade sector, dividends paid are often stated on a per-share basis or the total amount that is paid at the end of a financial year for companies. The dividend rate can be calculated using either of the two values. In this case, the total amount paid is provided (Boulanger & Philippidis 2015). Therefore, the dividend rate was the quotient of the annual dividend by the value of the preferred stock that is issued and outstanding for the sampled stocks (García-Herrero & Xu 2016b).

Dividends in arrears are those that have been declared by an entity and they have not been paid. The net income that is generated at the end of a financial year can either be paid out as a dividend or retained by a company (Irwin 2015). If a company pays dividends, then the value is deducted from the retained earnings balance. According to the cumulative dividend feature, preferred stockholders must be paid both current-year dividends and any dividends in arrears before dividends to common shareholders are paid. The calculations of retained earnings balance presented in the attached excel file are based on the assumptions that the dividends in arrears were declared and that there are no retained earnings restrictions (Kraft 2013).

The resulting value of retained earnings after deducting dividends in arrears and current years’ dividend. If the dividends in arrears have not been declared, then the retained earnings balance will not be reduced by the number of dividends in arrears. The ratio is also a measure of efficiency. That is, how effectively the management makes use of resources that are provided by shareholders to generate profit (Armstrong & Portes 2016). A high value of the ratio is an indication of elevated efficiency. A comparison of return on equity should be carried out for companies that operate in the same industry. This is based on the fact that some industries tend to have lower values of return on equity than others (García-Herrero & Xu 2016a). Since the research focused on the entire sector, there is a need for a further study to explain the variations in dividend fluctuations, especially during the last stretch towards the Brexit vote and projections into the future (Kraft 2013). This means that the researcher will concentrate on the stock return ratio to observe the positive or negative financial performance of sampled companies as an explanatory variable of Brexit as impacting trade in the UK (How important is the European Union to UK 2015).

Literature Review Limitations and Filling the Gaps

There is a literature review gap in the empirical studies that relate to the potential challenges that the UK might face after Brexit. Among the notable challenge highlighted include disruption of the labor market, trade imbalance, and slow economic growth in the short run. Opportunities identified in the empirical literature are expanded economy, improved labor market, and independence in trade agreements in the long run. This study will fill this gap by attempting to weigh and compare the correlation between factors associated with the loss of human resources and immigration. Moreover, the existing literature could not explain how the current economic variables in the UK trade would be properly transitioned into the post-Brexit model to gain optimal returns following new trade arrangements and agreements.

The proposed research study will attempt to fill this gap by evaluating each factor as an independent entity and relate them to the potential overlapping impacts. At present, the researcher could not identify a past study explaining the relationship between the economic impacts of different foreign direct investment opportunities that will be lost or gained following Brexit. This research gap should be filled by carrying out a study to verify the correlation of positive and negative impacts associated with the FDIs after Brexit. The proposed study will examine these factors concurrently. Lastly, the proposed research will attempt to establish how the governance challenges should be addressed to create the most beneficial outcomes in the long term. Specifically, the political problems and outcomes are part of the government intervention machinery in the trading metric. This means that the analysis will expand on government goodwill and general public perception of the Brexit debate in terms of their direct and indirect impacts on the UK trade sector.

Summary

The literature review suggests that Brexit is laden with opportunities and challenges. Among the noted benefits include improving international and regions trade ties, independent and faster trade deals, expanding economy, and opportunities for forging wider trade networks across the globe without interference by the EU. The challenges are divisive debates around the economy and social welfare, political, protest, speculative uncertainties, and potential impacts of a failed Brexit. However, the benefits may surpass the limitations when the post-Brexit economic environment is strategically managed and effectively implemented in an inclusive economic and social environment. Several empirical studies indicate that the UK might lose in the short term due to disruptions in trade and extra investment in resources to make the adjustments. Through the application of the trade model, the past literature suggests that the positive benefits of Brexit can only be realized in the long term since the UK government will be in a position to negotiate for better trade agreements.

Methodology

Introduction

This section of the study examines the appropriate research design for data collection and subsequent analysis. The research will be conducted using a quantitative survey of secondary data consisting of official data on trade performance before Brexit and projected data for the time when the UK will exit the European Union. The choice of quantitative research design was informed by a need to carry out a comprehensive analysis of sector-based data on trade in the UK following Brexit. Moreover, the researcher will be able to understand the variables in play through a comparative analysis. This means that stock return is the dependent variable while variations in financial performance will be the independent variable (Battor & Battour 2013). This part of the report will review data from several reputable sources over nine years, that is, projected data from 2015 to 2022 to identify any pattern in the performance of trade before and after the Brexit vote.

Research Design

Researchers have numerous modes of data collection and analysis at their disposal. The method of data collection selected depends on the availability of information, funds, and time. Some of the widely used methodologies include triangulation, surveys, and case studies. Currently, there is limited information about the link between Brexit and the performance of trade in the UK. Additionally, the existing data elucidate limited information about trade industry trends. Thus, to come up with general findings, there is a need to rely on the triangulation method through the application of the Cohen’s d formula in calculating the effect sizes of the study and a Comprehensive Meta-Analysis formula. The research will be performed using a quantitative research approach by undertaking a focused survey of published data on trade from the government of the UK website and other formal organizations dedicated to trade performance analysis.

The reason for picking quantitative design was to comprehend the dynamics around trade performance in the UK market before and after the Brexit vote to predict the future trend (Batsaikhan, Kalcik & Schoenmaker 2017). Moreover, this approach will enable the researcher to carry out an explicit analysis of collected data using different integrated tools such as ANOVA and regression among others to verify the assumption limits and error margin. The use of the quantitative research approach will also facilitate a comprehensive understanding of the existing relationship between variables of trade and how they react to Brexit (Bloom 2014). This means that the researcher will be in a position to study these attributes through observation of trade trends from data mined from different official sites (Bryman & Bell 2015). It is expected that these tools will facilitate the accurate establishment of trends from data collected.

Selection of Dependent and Independent Variables

Under financial performance, the researcher focused on variables of trade growth within the UK to study their performance under the period of study. Isolation of stock return ratios will make the analysis more focused and easy to follow for the trade sector. Moreover, the stock return is a strong indicator of positive or negative trade performance and organizational and industry levels (Bloom, Draca & Reenen 2016). This means that stock return is the dependent variable while variations in financial performance will be the independent variable. This means that an increase in stock returns would signify improved financial performance and vice versa.

Sample Selection and Sample Size

The researcher intends to use focused convenience sampling, which involves randomly selecting the sample population within a pool with more or less similar characteristics. This method will be carried out by focusing on three reputable sites in data mining to establish the trend in trade performance in the UK for over nine years. Specifically, the samples will be picked from the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the UK government’s publications. Moreover, the researcher will also review existing empirical literature from reputable institutions and individual authors to discuss the trends from the final inferences (Daft & Marcic 2016). The rationale for selecting a focused convenience sampling approach was the need to save time as opposed to primary research, which would have taken a longer period to process (Denscombe 2015). Moreover, convenient sampling of the secondary data would guarantee accurate results since different sources will be consulted (Egger et al. 2015). In generating the sample size for the proposed study, the researcher opted to use the formulae created in 1972 to ensure research dependability as explained below (Irwin 2015). Research dependability means aligning the scope of the study to acceptable scientific analysis standards. Specifically, the research will consider the performance of stock return indicators before and after Brexit for nine years.

n=N/ (1+N (e2))

Where:

- n = Size of sample

- N= Population targeted

- e= Degree of freedom

- n=30/ (1+30*0.052)

- n=30/1.075

- n= 27.9

As explained by the Central Limit Theorem, which is a sample space verification tool, a sample size above 25, as is the case with the proposed study, ensures that the X-Bar is normally distributed across the samples, irrespective of the population shape or other dynamics (García-Herrero & Xu 2016). Therefore, the study will target all trade companies listed in the stock exchange with a special focus on the proposed sample size of 27.9 for the research.

Analysis Methods

Data analysis: Secondary data collected from different sites and publications will be examined individually and then analyzed through the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). During the process of coding, the researcher will use cross-tabulation to carry out a comparative analysis of the existing association or correlation between trade performance in the UK before and after the Brexit vote. To establish the existing correlation between the dependent and independent variables, the researcher will carry out a regression analysis in addition to the use of charts, figures, and tabular representation of the research results (Guiso et al. 2015). During the regression analysis, software such as Excel, Google Docs, and eViews will be integrated on a need basis.

Proposed conceptual framework using Cohen’s formula

This research will be based on evaluation methodology through the application of the Cohen’s d formula in calculating the effect sizes of the study and a Comprehensive Meta-Analysis formula. The use of this formula will enable the researcher to establish the means score of the sample size from the relationship between the dependent and independent variables will be analyzed. Moreover, this function allows for probing the pre-tests and post-tests of the sample population for its authenticity. In this case, x1 and x2 will denote mean scores while n1 and n2 are sample sizes.

Proposed regression model

Reviewing the existing correlation between trade performance and Brexit, the researcher will use the ordinary least square regression as explained below.

Y = α + β1X1

Where,

- Y = Stock Return (dependent variable).

- α =Value of Y at the point where explanatory variables’ values are zero (Guiso et al. 2015).

- X = Variation in financial performance as explained in section 3.3.

- β =Parameter indicating an average alteration in Y; associated with each unit alternation in variable X (Guiso et al. 2015).

- X= Independent Variable as explained in section 3.3.

The data for Y and X will be obtained from government websites and other trade-related sites summarising stock return performance for selected companies (see appendix 2 and 3). About the UK trade performance before and after the Brexit vote, X1 will represent the ratio of changes in organization performance (Bryman & Bell 2015).

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

Another important instrument that will be used in the research study is the analysis of variance (ANOVA) to pinpoint statistical patterns in the secondary data collected. The two elements of ANOVA analysis are means of stock return variation

and changes in organizational financial performance

, which means that high stock returns will signify improved financial performance, thus, a better trading environment (Bryman & Bell 2015). Thus, the null and alternative hypotheses for the ANOVA were created as;

Null hypothesis

Ho: µ1 = µ2

The null hypothesis implies that the selected sample population mean on stock return performance before and after the Brexit vote is equivalent to the mean for the entire population segment. This means that financial performance at the sectoral level will be similar when subjected to Brexit.

Alternative hypothesis

Ho: µ1 ≠ µ2

The alternative hypothesis implies that the selected sample population mean on stock return performance before and after the Brexit vote is not equivalent to the mean for the entire population segment. This means that financial performance at the sectoral level will not be similar when subjected to Brexit.

From the above hypotheses, the null hypothesis will be not be accepted at the point when F-calculated is bigger compared to the F-critical at the 99% interval in the data collected for stock return and variation in financial performance. Blaxter et al. (2013) note that the ANOVA instrument is significant in establishing the difference in mean of a data set collected through disintegrated variations. About this research study, the analysis of variance instrumentation will be used to present and quantify observable statistical variations between means of each data set for stock returns and variation in financial performance. The confidence interval in this research study will be estimated at 99% using the Cohen formula. This is a standard equation used to estimate confidential intervals. The values of b1 at different intervals are estimations (see appendix 2 and 3).

Sample statistic + Z value * standard error / √n (Guiso et al. 2015)

b1 = 7.1175 ± 2.57 * 0.9631 / √133

= 7.1175 ± 2.57 * 0.9631 / 11.5326

= 7.1175 ±0.2146

= 6.9029 ≤ b1 ≤ 7.3321

At 95%

b1 = 7.1175 ± 1.96 * 0.9631 / √133

= 7.1175 ± 1.96 * 0.9631 / 11.5326

= 7.1175 ± 0.1635

= 6.954 ≤ b1 ≤ 7.281

At 90%

b1 = 7.1175 ± 1.64 * 0.9631 / √133

= 7.1175 ± 1.64 * 0.9631 / 11.5326

= 7.1175 ± 0.1368

= 6.981 ≤ b1 ≤ 7.254

From the above computations, the estimated confidential interval is at 6.981 ≤ b1 ≤ 7.254 of 90%, 6.954 ≤ b1 ≤ 7.281 of 95%, and 6.9029 ≤ b1 ≤ 7.3321 of 99% (Guiso et al. 2015). These calculation results suggest that confidential interval estimates increase as interval levels decrease. The “application of the ANOVA is focused on quantifying the existing variance in different sets of data by disintegrating the differences existing in the sets for each transcribed group” (Kothari 2013, p. 56). Therefore, in this research study, the ANOVA analysis will present the data sets mean differences for each organization from the perspective of stock return ratio (see appendix 1).

Dependability and Reliability

The researcher will guarantee dependability by providing detailed, sequential, and clear data collection, description, and analysis. Specifically, the proposed research design will ensure that data analysis and interpretation is congruent with the research questions. Moreover, the theoretical construct and different analytical frameworks will facilitate a smooth transition in the inferences within meaningful parallelism for the secondary data sources by relating the findings to existing literature to establish consistency in the highlighted trend (Kothari 2013). For instance, the researcher will be able to draw scientific inferences and perform a comparative analysis of the results with previous empirical findings.

Generalisability and Vigour

The relatively large sample space selected presents scientific, verifiable, and clear criteria for tracking projected stock performance trends before and after the Brexit vote within the trade sector in the UK. Based on the above strengths, the proposed sample size is a representation of the space and scope at specific intervals as discussed before. Moreover, the representative sample will give room for a comparative analysis (Trommer 2017). As a result, it will be possible to test the degree of biasness and accuracy. Therefore, the secondary survey will be a hallmark of accurate population representation and strength of the proposed study.

Ethical Considerations

During the entire period of study, the researcher intends to uphold different ethical principles relevant to the scope and nature of the research. For instance, the researcher will only select data from reputable sites. With adequate experience and training in data collection and analysis, the researcher will not face major challenges in coding and transcribing the raw statistics. The credibility of the study will be enhanced by integrating distinct quantitative design in gathering, analysis, and interpretation of collected data to create an accurate inference (Yu et al. 2017). The aspect of transferability in the collected data and results will be made possible by using a relatively adequate sample, which is representational of the data population.

During the period of the entire study, the researcher has put in place strategies for ensuring the accomplishment of scientific research requirements. For instance, the researcher will seek authorization from the relevant websites to ensure that data collected is accurate and representational of the study scope. To enhance credibility, the researcher will use quantitative survey and qualitative observation approaches to collect relevant data and draw inferences. Moreover, result transferability is theoretically possible through using adequate sample space that is representational of the studied population. The researcher will integrate the Scientific Research Code of Ethics (Bryman & Bell 2015).

Methodology Justification

The use of quantitative research design was necessary since the study aims at understanding the existing correlation and variations in stock return for thirty companies within the UK market before and after the Brexit vote. This means that quantitative analysis creates an ideal environment for comparative analysis of dependent and independent variables (Liu, Shang & Han 2017). The proposed study will be concentrated in the selected trade sector (Oliver 2016). Thus, the scope of this study will encompass an examination of the research magnitude from the results addressing the research topic, which is the impact of Brexit on the performance of trade in the UK.

Potential Biases and Minimisation

Since the researcher will depend on availability and published secondary data, it might be difficult to prove the authenticity of some data, especially in instances of missing information (Smetana 2016). To minimize this bias, the study will concentrate only on officially published data in addition to consulting other sources such as conferences and reports for authenticity (Sampson 2016). Since data was gathered from quantitative research, it is possible to have some level of biasness and erroneous data on trade performance (Kothari 2013). The sample consisted of thirty companies, thus, the study may integrate a relatively shallow data set (Bryman & Bell 2015). The collection of accurate data was difficult since some companies did not have updated information (Matthews 2016).

Therefore, the researcher was unable to compare the existing and past stock returns in some instances, especially the projected data on stock return in agriculture-based companies (Smith 2017). However, this challenge was minor and did not affect the outcome. The researcher intends to subject quantitative data sets to coding to guarantee dependability and consistency. For example, each data set will be coded to reduce generalization bias using sub-sector and similarity indices (see appendix 2 and 3) (Bryman & Bell 2015). The data will be selected from reputable sites and collected through observation and recording. Specifically, “thematic and content analyses will also be closely observed to ensure that findings fall within the context of the study” (Sherif 2018, p. 60). To minimize biases associated with quantitative data, the research will use official data from government institutions and only refer to other sources to confirm the existing trend (Full report-graduates in the UK labor market 2013 2014).

Expected Results

It is expected that Brexit has an indirect and direct impact on stock returns concerning the performance of trade within the UK (Kraft 2013; Rojas-Romagosa 2016). The collected published data indicated that trade has expanded in the last nine years, especially in the financial sector (Mason 2017). The reason for considering a single sector in the data analysis was to avoid the segregated data set associated with integrating many sectors (Singh & Singh 2014).

Resources and Costs Involved

Resources: The data collection and analysis will be based on three reputable sources, that is, the UK government, IMF, and World Bank publications, which have adequate information to cover the sample population. Moreover, the researcher will consult academic books, financial journals, and reputable sites (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill 2016).

Costs: The cost of the entire study is expected to be less than $200 since it is focused on secondary data. Specifically, some sites will require a subscription to access data.

Summary

The evaluation methodology has been selected to draw inferences and conclusions in this research study. The quantitative research design was chosen in data analysis and interpretation, inclusive of the significance of observation, context evaluation quality, and proactive interpretation. The proposed dependent and independent variables are stock returns and ration of financial performance before and after the Brexit vote for a cumulative period of nine years running concurrently from 2015 to 2022. The relatively limited sample may reduce the general research insight. However, each set of data will be probed to minimize bias and promote accuracy in drawing inferences. The reason for selecting a quantitative design was to ascertain insights in stock returns and relate them to the trade trend from secondary data over nine years. The secondary data will be collected mainly from reputable sources, which are the government of UK publications, the World Bank, and the IMF. Other sources such as financial journals, dedicated institutions, and books will be consulted in the analysis. The expected findings based on the literature review are that Brexit will have a direct and indirect impact on trade performance.

Findings and Discussion

Findings

The average MFN tariff of the EU was 5.5% by the end of 2013. However, it is currently difficult to ascertain the specific tariffs that the United Kingdom will have to face following Brexit since the EU is expected to apply varying tariff rates for each product grouping that the UK will export to other parts of the European Union (Boulanger & Philippidis 2015). As captured in table 1 (see appendix 1), the cost incurred for exporting products to other parts of the EU is predicted to rise if the current trend persists after Brexit.

Trend Analysis

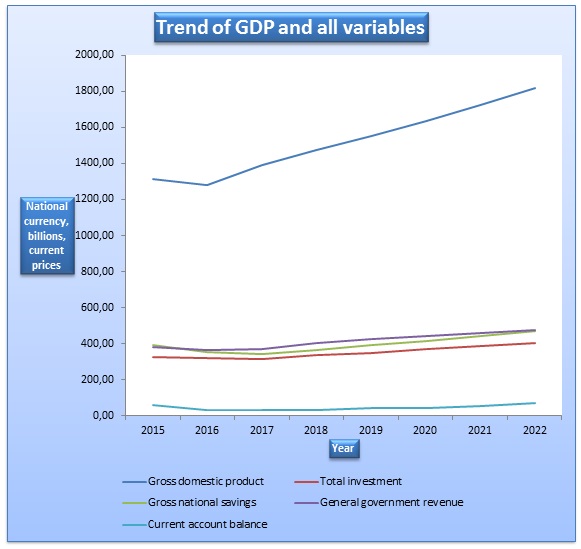

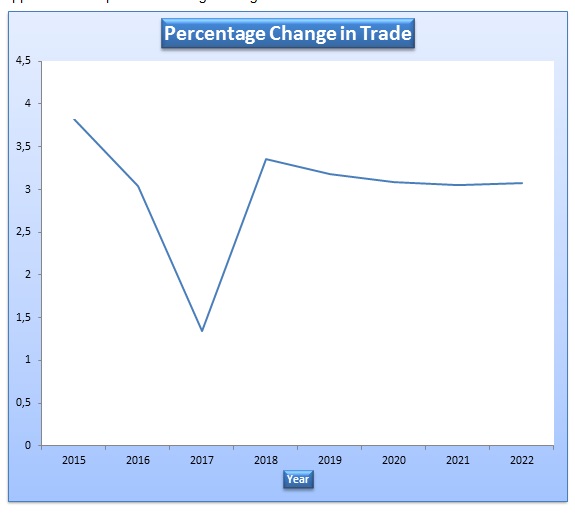

The GDP trend as part of the variables was examined from 2015 to 2017 and projections up to 2022. The results were tabulated as captured in graph 1 (see appendix 2). Graph 1 indicates that the UK had a decline in GDP during the period of Brexit debate, present account balance, national savings, investments, and revenues in 2016, especially in the stretch leading to the vote. However, these values are projected to expand in beyond 2020 since the market is expected to positively respond in the long-term (see appendix 3 and 4). This indicates that Brexit might catalyze economic growth in the UK. Regarding trade changes as percentages, the trend in growth in trade as summarised in graph 2 indicates a downshift between the years 2015 and 2017 (see appendix 5).

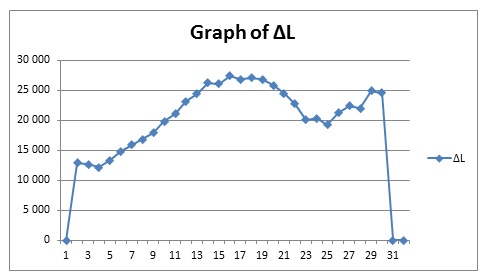

However, Brexit and other economic variables are expected to result in an expansion in 2018 since the immediate market reaction will subside. Thereafter, “the country is likely to experience steady growth in trade after Brexit and beyond” (Gisondi 2017, p. 17). As captured in graph 3, the trend analysis of the performance of trade shows that the UK experienced a growth in revenues (see appendix 6). This was sparked by intensification in trade opportunities and an optimistic attitude towards the Brexit vote. This means that Brexit is expected to create an expansion in the trade since the UK will be in a position to renegotiate trade deals. Therefore, the trade sector is projected to perform better after Brexit as observed by the continuous trend in revenue growth.

Regression

The following regression line was used to examine the relationship between dependent and independent variables;

Y = b0 + b1X1 + b2X2 + b3X3 + b4X4

- Y = GDP in £, billions

- X1 = unemployment, percentage

- X2 = current account balance

- X3 = trade sector revenues

- X4 = retail sector revenues

The theoretical expectations are b0 can take any value and b3, b2, and b4> 0, while b1 < 0 (Yu et al. 2017).

The regression equation took the form Y = 231.49 – 33.34X1 + 0.82X2 + 1.52X3 + 1.05X4 (Guiso et al. 2015). The trade coefficient is positive indicating that there exists a positive correlation between trade and GDP in the UK (Buddi 2017). The positive coefficient indicates that a rise in any variable results in an increase in the GDP by a similar coefficient value. According to Dobiles (2017, p. 19), a “two-tailed t-test is used to test the significance of the explanatory variable”. In this case, the t-statistics for trade sector revenue is 4.0272 with the p-value being 0.0275 (see appendix 7). Since “the p-value is less than α=0.05, then the null hypothesis is rejected and conclude that the variable is a significant determinant of GDP” (Dobile 2017, p. 21).

The p-values generated as larger than Alpha, which indicated that they statistically insignificant (García-Herrero & Xu 2016a). The t-test results could have been altered by the correlation between the dependent and independent as summarised in the matrix above. Specifically, the f-calculated value is 234.5132. The f significance value (0.0004) is not greater than α (0.05), which is an indication that the regression line is significant statistically at a confidential interval of 95%. Moreover, the R-square value is 0.9879 while R-square adjusted is 0.9935 (see appendix 8). Since R-square measures the fit better, the derived value almost close to 1 suggests that the independent variable has a stable power since it expounds 99.67% GDP variations. These results indicate that the GDP of the UK will be influenced by trade sector revenues after Brexit.

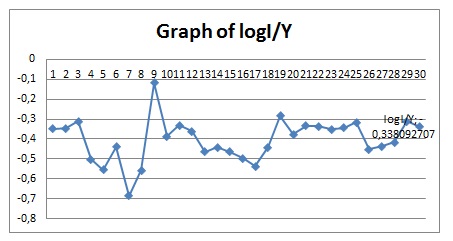

Model Summary

The R2 value depicts 0.672 of the variations are explained by the total variation. The coefficients of beta for L-0.014, D-0.652, and D/Y-0.381 affect the variations with these weights. The three variables vary uniquely with each having a different prediction (p) for L-0.08, D-4.138, and D/Y 2.170 (see appendix 9). The significance of the variables as indicated by the ANOVA table (p=0.002) shows that the model is significant (Dobiles 2017). The variations of the variables as depicted by R2 compared with adjusted R2 have no large difference, which indicates that the variables are related and interdependent (see appendix 9). This means that the stock return is interdependent on the performance of the trade. The positive trend suggests an optimistic outcome following the Brexit vote. As captured in appendix 10, graph 4 depicts the high growth of the trade sector in the country as predicted in the next five years. The contraction of trade growth between 2015 and 2017 is due to immediate market reaction to Brexit debate after which, it is projected that the trade sector will recover and record improved growth. Moreover, as captured in graph 5, the ratio of a trade investment share of real GDP is negative (see appendix 11), which depicts low investments and a bigger portion of the income has to be used in expenditures rather than in investments to effectively manage Brexit expectations.

Correlation Matrix

Correlation matrix (from covariance analysis) of the variables: the growth of the real GDP (at constant prices), the growth of trade, the ratio of the investment share of real GDP, and the ratio of an investment share of trade. Table 4 on correlation indicates that there is no connection between investment in trade share and the growth of the trade sector (see appendix 13). Testing the overall significance at a 5% significance level of independent variables on the dependent of the model was carried out to establish the degree of confidence with a variation of 5% (see table 5) in appendix 13. Heteroscedasticity does not exist as the correlation matrix depicts. The high dispersion of variables is not a cause of heteroscedasticity (see appendix 13). The model is consistent and significant because the correlation matrix indicates the values of each variable from the matrix have constant variance (Geddes 2013). Heteroscedasticity does not exist because it is below significant levels. The absence of heteroscedasticity indicates that the variance of the data is limited. Multicollinearity does not also exist as the model’s two-tailed test value of significance is zero (see appendix 14). The variables are covered explicitly by the model (Gisondi 2017). Also, there is no autocorrelation indicating that the values are not correlated. This means that Brexit will not negatively affect trade in the long-term, but will present growth opportunities.

The Brexit debate is expected to have a direct impact on private and public ventures due to government participation in trade policy formulation and implementation. UK stands to lose important allies who are currently members of the EU. Oliver (2016) noted that even though a successful Brexit is likely to attract more economic opportunities, surviving the negative impact of the voter referendum in an already fragile nationhood fabric might prove to be a challenge. Specifically, the vote margin for proponents and opponents of Brexit was less than 2% (Thompson, Espinoza & Mance 2017). This means that the political class will have to convince 48% of the votes to embrace the post-Brexit environment. This means that the UK is facing an imminent backlash from the opponents of Brexit in the event of prolonged challenges (How important is the European Union to UK 2015). This trend is predicted to persist in the post-Brexit environment as the UK companies will have expansive markets to export to without unnecessary regulations from the EU.

Since the UK presently acts as the trade facilitator between China and the EU, the exit will reduce the trade deficit for other members of the European Union while increasing the surplus for the United Kingdom (Geddes 2013). Gracia-Herrero and Xu (2016a) note that the pre-exit foreign investment from China in the UK from 2010-2015 reached EUR15.16 billion. Therefore, losing membership would have a ripple down effect on the short term foreign investment strength for the UK economy due to adjustments and withdrawal of the neighboring investments from London and other major cities (Boulanger & Philippidis 2015). However, the effect is only short term since trade negotiation in the post-Brexit will only benefit the UK economy unlike the current EU community model (Armstrong & Portes 2016).

As a result, companies based in the UK and the general trade sector will experience improved financial performance as more products and services are absorbed by the market. Moreover, the UK economy will be positively positioned to expand further following improved trade (Kraft 2013). For instance, other factors of production will be positively skewed to gain from the projected boom, especially when Brexit is properly implemented. Also, the positive results for projected financial performance within the trade sector are a sign of many opportunities for robust economic growth and development, especially in the long term (Armstrong & Portes 2016). These results concur with the literature review findings which suggested benefits such as expanded economy, improved purchasing power, stronger UK pound, and improved general economic environment. Therefore, there is a need for a sober, expert-guided, and government-supported process of Brexit to realize these benefits in the short and long term (Rojas-Romagosa 2016).

The UK faces economic instability following the Brexit debate. The “financial system of the country heavily relies on the income generated from exports within the manufacturing industry” (García-Herrero & Xu 2016b, p. 45). Since the UK pound will no longer be pegged to the Euro pound, the exchange rate fluctuations may affect its GDP (Geddes 2013). The consistent economic growth in the UK over the years has resulted in the expansion of the labor market. This has “contributed to an upsurge of labor cost, thus increasing the cost of operations” (How important is the European Union to UK 2015, p. 9).

The economic impacts of Brexit will have similar or even higher challenges on other EU member states trading with the UK. Batsaikhan, Kalcik, and Schoenmaker (2017, p. 24) argue that “London has been the hub of financial activity for a long period and the exit of UK from European Union will mean that 27 partnering countries of EU will lose the license to operate in the UK”. Unfortunately, a shift in the financial and trading hub from the UK to another EU state would have diverse negative impacts on UK’s competitiveness and might force the local firms to suddenly readjust (Bloom, Draca & Reenen 2016). Although the readjustment is short term, its effect could result in reduced GDP by up to 5% (How important is the European Union to the UK 2015). Trommer (2017) notes that UK must establish a new trade defense away for the EU for its local market in addition to signing agreements with international partners to survive the interruption of the trading system in the EU.

According to Gisondi (2017), income elasticity measures the association between the change in quantity demanded a commodity and change in income. Income elasticity is arrived at through the division of a percentage change in demand by the proportionate change in income. The coefficient of income elasticity varies depending on the commodity. For instance, normal goods have positive elasticity. If the income elasticity is less than 1 but greater than zero, then the commodity is a necessity. This implies that as income increases, the demand for the commodity grows (How important is the European Union to the UK 2015). It showed that the income elasticity of demand for food in rich countries tends to be lower during economic stability than during times of uncertainties.

For instance, in the UK, the poorest 20% of the households spent 16.6% of their income on food, while the entire household spent 11.6% on food (Rojas-Romagosa 2016). One factor that can explain this difference is that consumers in the UK spend a small proportion of their income on food, which is a necessity. Thus, fluctuations in the income level in the event of a failed Brexit will affect the purchase patterns of the general population (García-Herrero & Xu 2016a). This implies that the demand for goods and services will be more sensitive to changes in income. In the end, this will affect the profitability of the surveyed firms and other companies due to reduced disposable income. However, a successful Brexit will ensure more disposable income, thus, increased profitability. However, the government might reduce the impact of failed Brexit by organizing high subsidies to farmers, reduced-Value Added Tax rates on food items, and low cost of food production (Armstrong & Portes 2016).

At micro and macro levels, the trade policies after Brexit are expected to have merits and demerits in short and long-term business engagements. Notably, business-related policy formulations in a specific market environment have weaknesses capable of attracting conflict of interest especially when the same policy functions in the international trade market scenario. Since the beginning of being a member of the EU, the UK has become an economic powerhouse in terms of an aggregate investment portfolio and economic growth (Armstrong & Portes 2016). The systematic and consistent rise is attributed to political and economic policies.

Due to deep-rooted culture of concentrated power in the hands of the politically established government, who have liberalized its market and facilitated internal investment by foreign investors, the UK offers attractive investment incentives and waivers on taxes to potential investors. Reflectively, this system is based on the ideology of totalitarian democracy. On the other hand, the prevailing positive economic climate in the economy of the Euro region offers unlimited opportunities to sellers to expand market territory from small streets to upmarket with ease (García-Herrero & Xu 2016a). In an attempt to capture attention in the global market, the UK has adopted the strategy of maintaining relative advantage through the exportation of goods and services tagged with competitive price as a policy. Over time, this strategy has paid off in the continents of the global market where the Euro region has created a market for every brand of its products irrespective of economic classes in these markets. This trend is expected to continue after Brexit since the UK will have even wider markets at regional and international levels.

Projected gains from intellectual capital after Brexit is expected to create expansive opportunities for trade in the UK. These opportunities act as an incentive for global investment in this region. The floating financial system will ensure a steady appreciation of the UK pound currency in the global business arena. The stability in the UK pound will place the United Kingdom in a strong business zone that is currently the preserve of the European Union and other first world giants. European region and the US has successfully transformed the economy and economic systems from traditional agricultural dominance into advanced and reliable service industry system consisting of international banking systems and liberalized private sector through its business policies (Bloom, Draca & Reenen 2016). These banking systems make credit available for entrepreneurs in the private sector and facilitate public borrowing. Subsequently, these economies have been expanded and a series of opportunities are available for internal and international investors. The potential interactions between the banking sector and private businesses in the UK and the European region after Brexit might make London the hub for entrepreneurship and the emergence of a wide market.

In any perfect competitive market, barriers to exit and entry are absent. However, the presence of barriers to entry eliminates the possibility of having a perfectly competitive market. These barriers to entry can either be initiated by market forces, legal, and technological factors (García-Herrero & Xu 2016a). The first most important barrier is economies of scale. This occurs when a firm has a significantly lower average cost than other entities in the industry. Secondly, a natural monopoly occurs if the industry technology and demand conditions cannot permit more than one firm to operate (Rojas-Romagosa 2016). In such a scenario, there is no price at which two firms can operate and cover their costs. Another factor is the start-up cost. If the cost of venturing into the industry or starting the business is high, then it can prevent entry into the industry. There are also policy-created barriers. These are government actions that deter other firms from entering into a specific industry.

For instance, the Brexit debate and general perception that UK-based companies within the EU bloc will have to move away might directly slow the growth of the economy through loss of income. Moreover, households depending on these companies might be forced to look for alternatives in the short term as a speculative measure (Armstrong & Portes 2016). However, these uncertainties are not good for the economy of the UK. Therefore, the government and other stakeholders should come up with acceptable strategies that might ‘calm down the economy’ away from ‘excessive speculative heat’ that might derail the entire process (Rojas-Romagosa 2016). For instance, the political class and business community should quickly move to reassure the UK citizens and international partners of stability and consistency during the process of implementing Brexit plans (García-Herrero & Xu 2016b). Also, the government might consider implementing a Brexit plan in stages to avoid the impacts of sudden changes in the economy, which are expected to negatively affect trade in the short term.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Conclusion and Recommendation

This research study was performed to establish the impact of the Brexit vote on-trade sector in the UK. This purpose was to study the consequences of Brexit for the UK trade sector. The aim was to relate these impacts on trade by establishing the implication and bearing of sector parameters to be able to form a single study. Another reason to carry out this study was to draw a scientific inference and suggest proposals for counteractive action against the unconstructive outcomes of Brexit. The researcher intended to find out the relationship between Brexit and the performance of trade indicators since this phenomenon has attracted a lot of positive and negative debates.

Through empirical and theoretical literature review, the researcher established that protagonists and antagonists of Brexit have genuine concerns on how it will affect the economy of the UK and the trade sector in particular. However, most of the past practical researchers predict that Brexit will have a positive impact on trade in the long-run, but might slow down this sector due to immediate market reaction. These findings are consistent with the inferences drawn by the researcher. For instance, the research study has established that Brexit is laden with many growth opportunities for the trade sectors from import and export perspectives. This means that the UK trade sector will have a liberalized trade policy that is not controlled or regulated by other weaker partners within the European Union.

Several both the contractionary fiscal and monetary policies have been used to control inflation in the UK. Some of the fiscal policies entail reducing disposable income by increasing direct taxes, reducing government taxes as well as the amount of government borrowing. The fiscal policies implemented have reduced the aggregate demand in the UK economy. However, this cannot be used to predict unemployment after Brexit since different causes of market volatility have different effects on other variables rather than unemployment only to focus on the growth rate. The model equates total income (Y) to a sum of expenditure in the economy. These expenditures are consumption (C), government spending (G), investment expenditure (I), and net exports (X-M).