Abstract

Idiopathic membranous nephropathy is a T-cell immune mediated glomerular disease. Natural history shows characteristic spontaneous remissions or progression to nephrotic syndrome or to end-stage renal disease. The first key in management is to differentiate between primary and secondary disease. Investigations aim at identification of the cause if present and assessment of the patient’s condition to identify predicting factors and response measures. Renal biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis. Treatment options are many but there is no universally accepted standard treatment regimen. This essay aims at reviewing the management of idiopathic membranous nephropathy.

Introduction

Classification of renal glomerular diseases can be according to pathology, aetiology, pathogenesis or clinical presentation, an example is a post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis, which represents an aetiological classification. Anti-glomerular basement membrane disease is another example that describes disease pathogenesis; in this context, idiopathic membranous nephropathy is a pathological description of glomerular disease. The term does not reflect aetiology; besides, only in 20% of cases, a precipitating factor can be identified (Short and Mallick, 2001). The disease may occur at any age, though commonly at middle age, with a 2:1 male to female ratio. There is no disease racial preference; however, it is more common in the White race and is the commonest cause of nephrotic syndrome in white adults (Fervenza and Schwab, 2008).

Aetiology and types

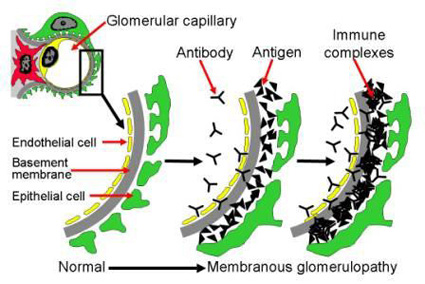

Idiopathic membranous nephropathy can be a primary disease with no detectable cause; however, in 20 to 33% of cases, there can be a cause for the disease (Fervenza and Schwab, 2008). In this case, the disease is secondary to an underlying disorder; yet, in either case, the term idiopathic membranous nephropathy describes a series of changes in the glomerular capillary wall (Cattran, 2002). The disease is an immune-mediated process that results in immune complex formation in the sub-epithelial glomerular layers initiating the capillary wall changes (Ronco and Debiec, 2006).

Ponticelli (2007) identified four stages of glomerular lesions in membranous nephropathy; the first is the presence of scanty small sub-epithelial deposits to the extent that the glomerular basement membrane may appear normal or minimally thickened by light microscopy. In stage two, immune complex spikes form and can be seen by light microscopy (need special stain) protruding through the basement membrane.

In stage three, the immune complex deposits are included within the glomerular basement membrane, and in stage four, the glomerular basement membrane becomes thickened because of the irregular reabsorption of the immune complexes (Figure 1). Green colour represents podocytes, grey colour represent glomerular basement membrane; the yellow line represents the capillary endothelial wall.

The disease is characterised by spontaneous remissions in many cases where complete reabsorption of the immune complex deposits produces lucent areas with the return of the glomerular basement membrane to normal (Ponticelli, 2007).

Ronco and Debiec (2009) suggested that neutral endopeptidase (a zinc-dependent enzyme expressed on podocytes’ surface) could be the first antigen to contribute to the immune reaction of idiopathic membranous nephropathy. They confirmed the link between an abnormal T-cell lymphocytes response and idiopathic membranous nephropathy.

Secondary idiopathic membranous nephropathy

Idiopathic membranous nephropathy may occur in association with many diseases with a ratio that differs in developed countries when compared with underdeveloped countries, probably because of differences in infectious diseases (like malaria and hepatitis) (Short and Mallick, 2001). Epidemiological studies show that membranous nephropathy correlates most commonly with diabetic nephropathy, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus eryhtromatosus and malignancy. Table 1 summarises the causes of secondary membranous nephropathy (Ponticelli, 2007).

Clinical-pathological correlation (natural history of the disease)

Provided no intervention occurs, the natural history of the disease ranges between complete or partial remission in nearly 40 to 50% of patients and disease progression. With complete remission, pathological changes disappear, proteinuria (the clinical hallmark of the disease) and renal functions stabilizes.

Alternatively, the disease may progress to end-stage renal failure. The rate of disease progression relates to many factors like age, renal functions, the extent of proteinuria at the disease onset, and gene polymorphism especially those controlling renin-angiotensin and nitric oxidase synthetase. In cases of disease progression, the mortality rate ranges from 6 to 20% a mean age of 50 years (Bruijn, 2006). Table 2 (after Ponticelli, 2007) shows the risk factors for death or progression to end-stage renal failure.

Diagnosis

The disease is more common in middle-aged males between 40 and 50 years and is the commonest cause of nephrotic syndrome in White males. Although the disease is rare in children; yet, it is commonly associated with other immune-mediated diseases. Nearly 60 to 70% of patients will present with a picture of nephrotic syndrome, the remaining 30 to 40% of patients present with vague complaints as anorexia, malaise and fatigability with accidental proteinuria usually less than 3.5 grams per 24 hours. However, patients with asymptomatic proteinuria may rapidly progress to the full picture of the nephrotic syndrome within a year or two. Microscopic haematuria is present in nearly 40% of patients; macroscopic haematuria or red cell casts are uncommon and usually suggest another diagnosis. Thirdly, at the time of presentation, most patients are normotensive as it relates to renal sufficiency (Fervenza et al, 2008).

Laboratory findings

Laboratory investigation results in idiopathic membranous nephropathy (IMN) point to one or a combination of the following: direct function of proteinuria, sequelae of progressing to nephrotic syndrome, or an underlying cause. Proteinuria in IMN cases is predominantly sized selective with an element of charge selectivity, IgG transferring clearance ratio is an indicator to selectivity and studies show levels of 0.2 or higher indicate poor selectivity. Besides microscopic haematuria, aminoaciduria and glucosuria (with normal blood glucose levels) are variable laboratory findings (Short and Mallick, 2001). C5b-9 is a pro-inflammatory mediator that triggers cell activation, which is found in the urine of IMN patients it should be considered an indicator of an active renal immunological insult (Chen et al, 2007).

Even in cases of heavy proteinuria, albumin serum levels may be normal because of hepatic compensation. Although changes in serum immunoglobulins levels are not consistent with IMN, serum IgG may show declined level while serum IgM level may increase. Abnormal serum lipoprotein levels point to the nephrotic stage of the disease (Short and Mallick, 2001). Complement components C3 and C4 levels are normal, except in cases secondary to systemic lupus (Short and Mallick, 2001).

Renal biopsy

Renal biopsy is the gold standard to diagnose IMN; light microscopy shows one or more of the stages described by Ponticelli (2007). Immunofluorescence microscopy is helpful in diagnosis and differentiating IMN from other immunological glomerular insult conditions (Brady et al, 2004). Electron microscopy is helpful in providing accurate morphological diagnosis to many renal diseases (Sementilli et al, 2004). Electron microscopy provides the potential to describe the stage of membranous nephropathy, identify early changes and differentiate the primary idiopathic form of the disease from secondary lupus type (Wagrowska-Danilewicz and Danilewicz, 2007).

Predicting factors and response measurements

Research evidence shows that renal survival, in terms of preserved renal functions and complete remission of proteinuria is the best response of IMN. In patients showing complete remission, 30% relapse to a sub-nephrotic stage of IMN but keep long-term stable renal functions. Thus, partial remission is also a positive outcome of the disease. No remission patients commonly show progression to insufficient renal functions and even to end-stage renal disease (Fervenza and Cattran, 2009).

Predicting the disease prognosis and severity is an essential element in choosing the therapy plan and which drugs to use. Thus, an exact predictor of IMN outcome would differentiate between patients for conservative treatment from those in need of therapy to stop disease progression. Finding such an exact predictor is difficult because of the variability of individual factors like age, gender, and selected biopsy findings (like degree of vascular or glomerular damage and interstitial fibrosis).

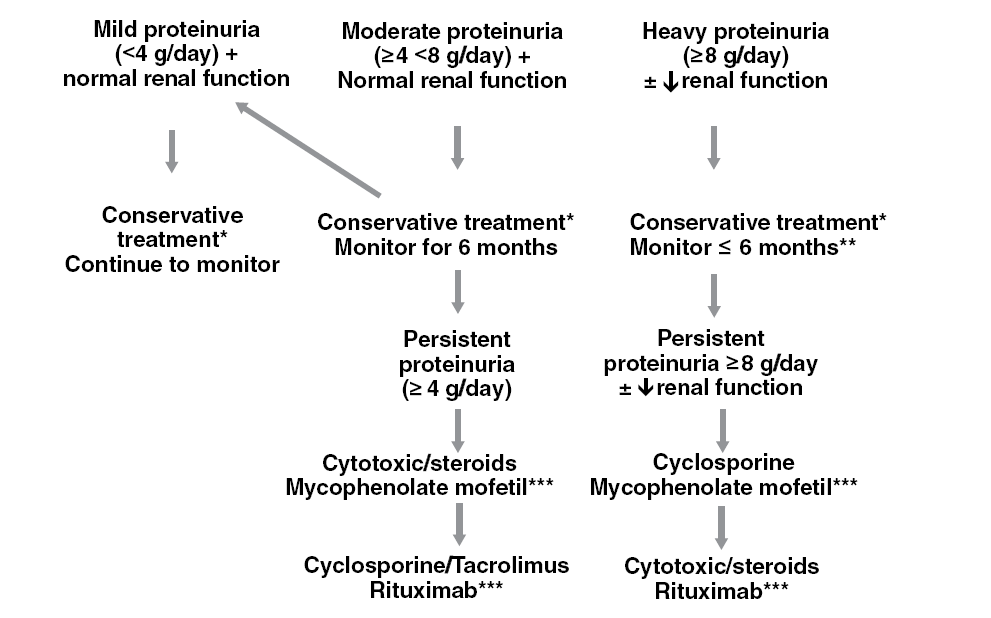

The first predictor to consider is the degree of proteinuria, research showed that patients with proteinuria more than 4 gm per day for 18 months show nearly 50% risk of progression. The risk increases steadily with heavier proteinuria to reach 66% risk of progression with more than 8 gm per day proteinuria for 6 months. Renal functions are expected to be a good predictor of outcome. However, they vary widely on presentation, besides; they may be independent of the disease severity, which is the reason glomerular filtration rate is used as an alternative predictor (Fervenza and Cattran, 2009).

Fervenza and Cattran (2009) suggested a model that identifies IMN patients at high risk, which considers the initial creatine clearance, the slope of the clearance curve, and the lowest level of proteinuria during a 6-month observation period. Based on the model described they suggested the treatment algorithm shown in table 3.

Treatment of idiopathic membranous nephropathy

Many believe all patients need conservative treatment because of the disease characteristic of spontaneous remission in many cases and the difficulty to agree on specific predictive factors of disease progression (Ponticelli and Passerini, 2001). Others recommend classifying the patients to low, medium, and high-risk patients based on current evidence and then starting treatment for medium and high-risk patients accordingly (Cattran, 2005). The third group of nephrologists advises using angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ARA) to all patients. Provided no or minimal proteinuria, patients are observed for up to 12 months for disease developments that mandate intervention (Praga et al, 2008).

This section of IMN management will provide a discussion on conservative treatment, steroid therapy, immunosuppressive treatment, rituximab and another newer drugs therapy.

Conservative treatment for idiopathic membranous nephropathy

The strategy of conservative treatment is to control dietary protein intake, control of blood pressure, oedema and prevent hyperlipidaemia. Restriction of dietary protein intake to 0.8gram per one kilogram of ideal body weight proved to reduce proteinuria between 15 to 25%; thus, slowing disease progression (Fervenza and Cattran, 2009).

Research evidence suggests that keeping the blood pressure around 125/75 prevents developing cardiovascular complications, reduces proteinuria and slows disease progression. Many studies agree that ACEIs and ARA drugs are effective antihypertensive agents besides having the capabilities to achieve the aimed strategy. However, it should be known that the degree of protection relates closely to the degree of proteinuria that is the lesser the proteinuria the greater the protective effect; further, ACEIs may not provide the same protection in IMN patients as it does for cases of diabetic nephropathy. A low salt diet is an important adjuvant measure to control the patient’s blood pressure (Fervenza and Cattran, 2009).

Lipid abnormalities that accompany proteinuria are high-risk factors for cardiovascular complications. Evidence suggests statins have a synergistic effect on ACEIs in reducing proteinuria; however, this effect is insignificant at proteinuria levels of less than 3 gm per day. It should also be noticed that combining statins with cyclosporine carries a high risk of rhabdomyolysis. Patients with high levels of proteinuria or those who passed to the nephrotic stage have a higher risk to develop thromboembolic complications; however, using prophylactic anticoagulant therapy has the risk of abnormal bleeding tendency. In IMN, patients with a high level of proteinuria (10gm per day or serum albumin <2.5 gram per day) are candidates for prophylactic anticoagulant therapy (Fervenza and Cattran, 2009).

Corticosteroids therapy in idiopathic membranous nephropathy

The fact that up to 40% of IMN patients pass to end-stage renal failure drove Kimura et al (2007) to examine the role of corticosteroid alone therapy in these patients. They conducted a retrospective study on 23 cases of primary IMN with moderate proteinuria (daily protein excretion between 1 and 3.5 grams per day). In their review, they suggested the 24-hour protein output relates significantly to the outcome of IMN. In addition, other research studies reported that steroid therapy alone induces remission (complete or partial) in nearly 70% of patients especially when administered in association with conservative measures. Research showed that neither short-term nor pulse steroid therapy results in a significant reduction of the 24-hour urinary protein output; however, with long-term corticosteroid therapy, complete remission occurs in nearly 60% of patients and incomplete remission in more than 35% of patients (Kimura et al, 2007). Kimura and colleagues (2007) examined the dose-response relationship and suggested a dose of 0.6 to 0.8 mg per kilogram body weight per day. Although the authors recognized the efficacy of steroid alone therapy in improving IMN patients, yet they also confirmed the need to study the efficacy of corticosteroids combined with other medications and the need to have large-sample prospective studies on corticosteroid alone therapy.

Jha et al (2007) performed a randomized controlled study on 93 IMN patients who progressed to nephrotic syndrome; they divided the patients into two groups. Group I (46 patients) received supportive treatment and group II (47 patients) who received a 6-months therapy course of alternating prednisolone and cyclophosphamide (a cytotoxic drug). All patients were followed for 10 years; results showed significant differences in remission rate (complete and partial) between the two groups. The 10-years dialysis-free survival showed significant differences; oedema, hypertension, hypoalbuminaemia and hyperlipidaemia were significantly less in the active treatment group. They inferred that a 6-months regimen of alternating cyclophospamide and corticosteroids can induce remissions, prevent disease progression and improves the patients’ quality of life.

The effect of combined steroid therapy with the newer drugs tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil was examined by Ballarin et al (2007). They administered low doses of steroids and tacrolimus to IMN patients whose proteinuria was higher than 1 gram per day (moderate cases). After three months they introduced mycophenolate mofetil in addition to patients whose proteinuria remained more than 1 gram per day. Treatment of both regimens was maintained for 12 months, results showed that treatment with steroids and tacrolimus produced higher remission rates; however, the relapse rate on discontinuation of tacrolimus was high. They suggested that the long-term results of this treatment need further research (Ballarin et al, 2007).

Immunosuppressive therapy of idiopathic membranous nephropathy

Based on the immune mechanisms of IMN and the few randomized controlled trials of using immune-suppressant medications to treat the disease, some authors advise using this group of drugs in treatment regimens. On the other hand, because of the lack of sufficient evidence of the benefit of these drugs besides their renal, hepatic toxicities and increasing the risk of infection, others advise using them selectively in patients at high risk of developing end-stage renal disease. This strategy is accepted by many authorities (Peggy et al, 2004).

Cyclosporine is the commonest immunosuppressant agent used in managing IMN, as it is known for suppression of cell-mediated immune reactions and, to some extent, humoral immunity. It specifically acts by selective and reversible inhibition of T-cell lymphocytes, T-helper cells and T-suppressor cells (Fervenza and Cattran, 2009).

Thomas (2006) performed a systematic literature review on evaluating the evidence of the role of cyclosporine therapy in IMN cases. Thomas (2006) inferred that cyclosporine produces remission rates higher than any other immunosuppressant-alkylating agent does, although relapses are common on discontinuation of therapy. However, there is a lack of evidence of the preservation of renal functions on long-term therapy. The author came up with the following conclusions: first, most studies used a divided dose of 4-6 mg per kilogram body weight per day. Second, in most studies therapy continued for 12 months after achieving remission, third, using cyclosporine as a single therapy is not advisable and when used with steroids, the combination produces better remission rates. Finally, they concluded that the relapse rate is between 30 to 40% within two years of drug discontinuation.

Newer medications for the treatment of idiopathic membranous nephropathy

Rituximab is an immunosuppressant drug used commonly as a second line when either steroid alone or steroids combined with cyclosporine fail to produce a remission (Bomback et al, 2009). In their systematic review on rituximab, Bomback et al (2009) reported two regimens for drug administration, first in a dose of 375 mg per square meter of body surface area administered weekly for four weeks. The second protocol is to administer 1 gram of the drug on days 1 and 15 to be repeated after six months if B-lymphocytes are equal to or more than 15 per µl. Using rituximab for primary IMN produced remission in 13 to 50% of patients. Bamback et al (2009) noticed that variations in remission rates between different studies link significantly to the definition of remission.

Rituximab administration in secondary IMN was mainly for case reports and the largest series included four patients, therefore, Bomback et al (2009) were not able to infer definite guidelines. Tolerance to rituximab was satisfactory and most side effects were mild and transient; however, two serious side effects were reported; first is laryngospasm and the second was the development of lung malignancy (Bomback et al, 2009). They inferred although rituximab has considerable potential for the treatment of IMN; however, current evidence shows its main use is in research so far. There are still essential questions to answer like when who and why to use the drug (Bomback et al, 2009).

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) is another second-line immunosuppressant drug used to treat idiopathic membranous nephropathy, which belongs to the newly developed selective immuno-modulating group of drugs. There are few clinical trials indicating initial success in treating refractory moderate to severe IMN cases; however, evidence is still lacking about the dosage, indications and duration of treatment (Thomas 2006, b).

Eculizumab is a new, humanized anti-C5 monoclonal antibody designed to prevent the cleavage of C5 into its pro-inflammatory by-products. In a recent randomized controlled trial (currently reported in abstract form only), 200 patients with IMN were treated every 2 weeks with two different intravenous dose regimens and compared to a placebo group, over a total of 16weeks. Neither of the active drug regimens of eculizumab showed any significant effect on proteinuria or renal function compared to placebo. It was later determined that adequate inhibition of C5 was seen in only a small proportion of patients, suggesting that the doses given were inadequate.

More encouraging results were seen in a continuation of the original study, in which eculizumab was used for up to 1 year. This produced a significant reduction in proteinuria in some patients (including two patients who went into CR). Whether complement inhibition with higher doses of eculizumab will prove to be more effective, as well as safe, in the treatment of IMN remains a question (Apple et al, 2002, after Fervenza and Cattran, 2009). To date, there are no standard first-line treatment options to apply universally to cases of IMN (Fervenza et al, 2008).

Summary

Idiopathic membranous nephropathy (IMN) is a relatively common immune-mediated glomerular disease and remains the leading cause of nephrotic syndrome in Caucasian adults. In the majority of cases, there is no aetiology (idiopathic). Secondary IMN links to autoimmune diseases (like systemic lupus erythematosus) and infections like (hepatitis B and C). It can also be secondary to medications (as a complication of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, penicillamine and gold), and neoplasia (e.g. carcinomas). Since idiopathic and secondary disease types have similar clinical presentations, it is crucial to rule out secondary causes of IMN. The management of these cases is directed towards removing or correcting the underlying cause (du Buf-Vereijken et al, 2005).

Treatment controversies are many because of a number of reasons; first, the disease’s natural history since a disease characteristic is with spontaneous remission and relapses. Second, there is great variability in the rate of disease progression, and the natural course is difficult to assess. Third, much of the data comes from studies that did not separate patients with both idiopathic IMN and secondary IMN and collectively reported treated and untreated patients. In addition, the majority of studies were conducted before the availability of agents that could potentially modify the natural course of the disease, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs).

Further, many studies reported spontaneous remissions in up to 30% of cases, usually in the first 2 years after presentation, but this may happen at any time over the course of the illness. Lack of standard predicting factors and response measurement is another factor to consider. The proportion of patients going into spontaneous remission is much lower when patients selected have higher levels of proteinuria at presentation. Patients who do not experience spontaneous remission are patients with either persistent proteinuria but maintaining adequate renal function or patients who will progress to kidney failure (Glassock, 2004).

In the light of the previous discussion, there are essential questions about treatment that need an answer like who to treat, when, and how to treat this chronic condition. Proteinuria is an inducer of kidney injury and plays a major role in the development of progressive tubular injury and interstitial fibrosis. The higher the sustained level of proteinuria, the more likely the development of end-stage renal disease is. Therefore, the main indication of immunosuppressive therapy is to accelerate the induction of remission, its long-term tolerance and value are still uncertain.

Treatment options vary from conservative treatment to aggressive immunosuppressant agents based on different algorithms of predicting factors and response measurements. In conclusion, control of proteinuria through complete or partial remission links to prolonged renal survival and a slower rate of renal disease progression. No orthodox or agreed-upon first-line specific therapeutic options for idiopathic IMN are available; accordingly, the place of second-line therapies is not yet clearly determined. All cases should follow conservative therapy, which should include using renal protective agents such as ACEIs and ARA and lipid-lowering medications. In patients who are at low risk of progression, conservative therapy should be enough, given their excellent prognosis, although long-term follow-up is needed to observe disease progression or alarming proteinuria.

Finally, as unsettlement are many, a treatment plan should be designed specifically for a particular patient according to presentation and condition. Patient follow-up, awareness of disease course, and education are essential adjuvant measures to effective therapy.

What I learnt

About disease management, it is a subject of variable understandings and interpretation. As described by Krumholz et al (2006) disease management is a structure that frames multiple domains; first is the patient population at risk, second are the primary targets for intervention. The third is the intervention content, which draws the individual components of health service; the fourth is the delivery personnel and the communication methods whenever there is a need. Fifth is the description of the frequency and duration of exposure to disease and or risk factors. Finally, is the treatment and clinical outcomes.

About idiopathic membranous nephropathy, it is an immune-mediated disease mostly caused by abnormal T-cell lymphocytes response. The T-cells responsible for the pathogenesis of nephrotic syndrome are immature rather than mature cells. However, the characteristics of the permeability factors produced by the T-cells are still unknown, in addition to the genetic basis for the abnormal T-cells lineage remains largely unknown. A crucial key to diagnosis is to differentiate between primary idiopathic and secondary types, as treatment targets the underlying cause in the latter.

In the idiopathic type, treatment focuses on minimising the risk of passing to nephrotic syndrome and subsequently to renal failure. Since many glomerular disorders may need a differential diagnosis, renal biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis but the decision needs careful decision-making procedure as those patients are prone to thrombo-embolic and abnormal bleeding complications. Radiological imaging investigations are not crucial to diagnose the disease but are pursued to diagnose an underlying cause or a complication.

About disease treatment, the treatment of idiopathic membranous nephropathy (IMN) is still controversial especially about the questions of when, how and who to treat. Many nephrologists believe that non-nephrotic patients should receive conservative treatment and be observed for disease development. Corticosteroids have an important part in treating the disease either alone or in combination with immunosuppressant agents. There are different regimens for immunosuppressant treatment based on algorithms of predicting factors and response measurements.

However, in the end, all regimens aim at the control of proteinuria through complete or partial remission, as this links significantly to prolonged renal survival and a slower rate of renal disease progression. Preliminary evidence on the use of newer drugs suggests these are agents that may be more effective, and safer, than current regimens, but it needs further assessment before being widely recommended. Patients with severe renal insufficiency (are less likely to try immunosuppressant treatment since the risk of treatment is significantly higher. Therefore, these patients are candidates for conservative therapy only and possibly for future transplantation.

About writing research, a research paper is the end result of an integrated process of critical thinking, evaluating sources, and organizing one’s thoughts. It develops as one reads and puts thoughts to paper because knowledge develops as information builds up. It is by no means a simple summary of a topic using primary and secondary references. It builds up systematic critical analysis skills, needs merging thought with supportive evidence, and how to write on a subject in one’s own words. This is not simple as it involves reading, understanding, assimilation and language skills. In addition to developing writing skills, from research, one learns how and where to look for relevant sources. Writing research is like building a pyramid starting with a wide base of information, organizing this information-driven by concepts and aims for writing, writing thoughts reinforced by supporting literature. The result is providing one’s perspective on the topic at hand.

References

Ballarin J, Poveda R, Ara J et al, 2007. Treatment of idiopathic membranous nephropathy with the combination of steroids, tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil: results of a pilot study. Nephrol Dial Transplant, (22), 3196-3201.

Bomback AS, Derebail VK, McGregor MC et al, 2009. Rituximab therapy for membranous nephropathy: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, (4(4)), 734-744.

Brady HR, O’Meara Y and Brenner, BM, 2004. Glomerular Diseases. In Eugene B, Fauci A, Hause S, et al (editors). Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 16th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional, 2004. Part 11, section 264.

Bruijn JA, 2006. Membranous Glomerulonephritis (Section II, 2). In Fogo AB, Cohen AH, Jennette JC, Bruijn JA and Colvin RB, (editors). Fundamentals of Renal Pathology. New York: Springer, 2006.

Cattran DC, 2002. Membranous nephropathy: quo vadis? Kidney Int, (61), 349-350.

Cattran DC, 2005. Management of Membranous Nephropathy: When and What for Treatment. J Am Soc Nephrol, (16), 1188-1194.

Chen Y, Yang C, Jin N, et al, 2007. Terminal complement complex C5b-9 treated human monocyte-derived dendritic cells undergo maturation and induce Th1 polarization. Eur J Immunol, 37(1), 167-176.

du Buf-Vereijken PW, Branten AJ, Wetzels JF, Idiopathic membranous nephropathy: outline and rationale of a treatment strategy. Am J Kidney Dis, 46, 1012–1029.

Glassock RJ, 2004. The treatment of idiopathic membranous nephropathy: a dilemma or a conundrum? Am J Kidney Dis, 44, 562–566.

Fervenza FC and Schwab TR, 2008. Nephrology: Part 1 (Chapter 17). In Habermann TM and Ghosh AK, (editors). Mayo Clinic Internal Medicine: Concise Textbook. Rochester, MN. Mayo Clinic Scientific Press.

Fervenza FC, Sethi S and Specks U, 2008. Idiopathic Membranous Nephropathy: Diagnosis and Treatment. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol, (3), 905-919.

Jha V, Ganguli A, Saha TK et al, 2007. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Steroids and Cyclophosphamide in Adults with Nephrotic Syndrome Caused by Idiopathic Membranous Nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol, (18), 1899-1904.

Kimura M, Toyodo M, Kobayachi, K et al, 2007. A Retrospective Study on the Efficacy of Corticosteroid-Alone Therapy in Membranous Nephropathy Patients. Intern Med, (46), 1641-1645.

Krumholz HM, Currie PM, Riegel B et al, 2006. A Taxonomy for Disease Management. Circulation, (114), 1432-1445.

Peggy WG, Buf-Vereijken D, Amanda JW et al, 2004. Cytotoxic therapy for membranous nephropathy and renal insufficiency: improved renal survival but high relapse rate. Nephrol Dial Transplant, (19), 1142-1148.

Ponticelli C, 2007. Membranous nephropathy. J Nephrol, (20), 268-287.

Ponticelli C and Passerini P, 2001. Treatment of membranous nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant, 16 [Suppl 5], 8-10.

Praga M, Polanco NE and Solis EG, 2008. When and how to treat patients with membranous glomerulonephritis?. Nefrologia, 28(1), 8-12.

Ronco P and Debiec H, 2006. New insights into the pathogenesis of membranous glomerulonephritis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens, (15(3)), 258-263.

Ronco P and Debiec H, 2009. Pathophysiological lessons from rare associations of immunological disorders. Pediatr Nephrol, (24), 3-8.

Sementilli A, Moura LA and Franco MF, 2004. The role of electron microscopy for the diagnosis of glomerulonephropathies. Sao Paulo Med J, (122(3)), 104-109.

Short CD and Mallick NP, 2001. Membranous Nephropathy (Chapter 63). In Schrier RW, (editor). Diseases of the Kidney and Urinary Tract. 7th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001.

Thomas M, 2006. Membranous nephropathy: role of cyclosporin therapy. Nephrology, 11(Suppl1), S166-S169.

Thomas M, 2006 (b). Membranous nephropathy: use of other therapies. Nephrology, 11(Suppl1), S172-S174.

Wagrowska-Danilewicz M and Danilewicz M, 2007. Current Position of Electron Microscopy in the Diagnosis of Glomerular Diseases. Pol J Pathol, (58(2)), 87-92.