Introduction

American Civil War (1861-1865) was a war between the Union and the Confederate States of America. There was massive loss to economic and social drain during this revolutionary war. There are numerous contradictory theories regarding the effects of the war on industrialization. This paper aims to ascertain the effect of the war on the on going process of industrialization in America. In the course of the paper, we will discuss the different theories prevalent as literature review on the subject and then try to relate them with the available empirical data to reach a conclusion.

Main text

The forerunner among civil war theorists were Beard and Hacker. Charles Beard labeled it “Second American Revolution,” claiming that “at bottom the so-called Civil War was a social war, ending in the unquestioned establishment of a new power in the government, making vast changes in the course of industrial development, and in the constitution inherited from the Fathers” (Beard and Beard 1927, 53). Hacker could sum up Beard’s position by simply stating that the war’s “striking achievement was the triumph of industrial capitalism” (Hacker 1940, 373). The “Beard-Hacker Thesis” had become the most widely accepted interpretation of the economic impact of the Civil War which believed that the impact of the war on American industrialization was profound.

Post World War II, a new group of economic historians questioned whether the Civil War, with its massive destruction and disturbance of society, could have been a stimulus to industrialization. In the 1990s a re-examination of the “economics” of the Civil War showed that industrial revolution actually did not catapult the growth, but the process was already paved before 1860s. it was during the war period that growth slacked down rather than contributing to it. As Thomas Cochran (1961) in his article “Did the Civil War Retard Industrialization?” pointed out that, until the 1950s, there was no quantitative evidence to prove or disprove the Beard-Hacker thesis.

Recent quantitative research, he argued, showed that the war had actually slowed the rate of industrial growth. Stanley Engerman expanded Cochran’s argument by attacking the Beard-Hacker claim that political changes were instrumental in accelerating economic growth (Engerman 1966). The major thrust of these arguments was that neither the war nor the legislation was necessary for industrialization which was already well underway by 1860. Critics argued that had there been no war the path of economic growth that emerged after 1870 would have done so anyway.

One key economic result of the civil war was it changed the U.S. from an essentially agrarian society to a country dependent on mechanization and a national market system. But its effects industry was uneven, ambiguous, and even contradictory. In 1860, America had a total of $1,050,000,000 invested in real and personal property devoted to business, with $949,335,000 concentrated in the North; Pennsylvania, New York, and Massachusetts each had a larger investment than the South as a whole. In the post war era this trend continued.

Goldin and Frank Lewis (1978); 1975 estimated of the costs of the war as presented in Table 1. The costs are divided into two groups: the direct costs which include the expenditures of state and local governments plus the loss from destruction of property and the loss of human capital from the casualties; and what Goldin and Lewis term the indirect costs of the war which include the subsequent implications of the war after 1865.

One body of evidence indicates that the war widened this sectional disparity by destroying the South’s minute industrial base and expanding that of the North to prodigious dimensions. Statistics on specific industries like cotton textiles provide what appears to be convincing proof. North’s largest industry, cotton textiles, saw a sharp decline due to the fall of agricultural produce in south. Sharp declines marked the production expansion of many Northern industries during wartime.

The nation’s railroads, for example, increased their trackage by 70% during the 1860s, as against over 200% in a brief period prior to the 1860s. The war saw only a 10% rise in the production of pig iron, though that industry had experienced a 17% increase 1855-60 and in the 5 years following approximately grew by 100%. Another striking comparison is the 3% decline in American output per capita in the 1860s, as against an average decennial increase of 20% for the balance of the period 1840-1900.

The southern states had enormous stake in its slave population. According to Ransom (1998, 56), the value of capital invested in slaves roughly equaled the total value of all farmland and farm buildings in the South. Slave labor was the foundation of a prosperous economic system in the South. To illustrate just how important slaves were to that prosperity, Gerald Gunderson (1974) estimated what fraction of the income of a white person living in the South of 1860 was derived from the earnings of slaves.

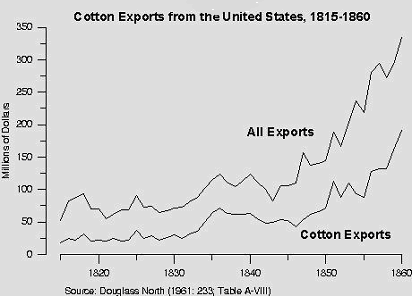

In the seven states where most of the cotton was grown, almost one-half the population were slaves, and they accounted for 31 percent of white people’s income; for all 11 Confederate States, slaves represented 38 percent of the population and contributed 23 percent of whites’ income. The Northern states also had a huge economic stake in slavery and the cotton trade. The first half of the nineteenth century witnessed an enormous increase in the production of short-staple cotton in the South, and most of that cotton was exported to Great Britain and Europe. Figure 1 charts the growth of cotton exports from 1815 to 1860. By the mid 1830s, cotton shipments accounted for more than half the value of all exports from the United States.

The income generated by cotton exports was a major force behind the growth not only in the South, but in the rest of the economy as well. Douglass North (1961), in his pioneering study of the antebellum U.S. economy, examined the flows of trade within the United States to demonstrate how all regions benefited from the South’s concentration on cotton production. Northern merchants gained from Southern demands for shipping cotton to markets abroad, as well as from the demand by Southerners for Northern and imported consumption goods. The low price of raw cotton produced by slave labor in the South enabled textile manufacturers to expand production and provide benefits to consumers through a declining cost of textile products.

The Civil War involved a huge effort to mobilize resources to carry on the fight. This had the effect of making it appear that the economy was expanding due to the production of military goods. However, Beard and Hacker mistook this increased wartime activity as a net increase in output when in fact what happened is that resources were shifted away from consumer products towards wartime production (Ransom 1989: Chapter 7).

In 1864 the Unions manufacturing index had risen to a level 13% greater than that of the country as a whole in 1860. But the war gave rise to no important new industries and generated no unusual increase in basic industrial production. Most of the innovations that did revolutionize American industry later in the century originated in the period 1820-60. Sharp declines marked the production expansion of many Northern industries during wartime. Perhaps a more enlightening ratio is the 22% increase in total American commodity output in the 1860s, compared to a 62% growth rate in both the 1850s and 1870s. Another arresting contrast is the 3% decline in American output per capita in the 1860s, as against an average decennial increase of 20% for the balance of the period 1840-1900.

Conclusion

Wartime statistics though shows an adverse effect on industrial growth fails to tell the full story of the civil war’s impact on American industrialism. Perhaps the primary economic effect of this period of turmoil was to prepare the economy for an intense industrialization in the decades following 1865. Definitely, the conflict helped remove all the industry-stifling government regulation, nationalized the regional market, and removed the energy-sapping political strife that had adversely affected industrialism prior to 1861 to bring a political party in long-term power that favored business growth. Thus, regardless of the immediacy of its effects, the war contributed much to the long-term economic climate that made a reunited America the industrial giant of the 20th century.

Reference

Beard, Charles, and Mary Beard. The Rise of American Civilization. Two volumes. New York: Macmillan, 1927.

Hacker, Louis. The Triumph of American Capitalism: The Development of Forces in American History to the End of the Nineteenth Century. New York: Columbia University Press, 1940.

Engerman, Stanley L. “The Economic Impact of the Civil War.” Explorations in Entrepreneurial History, second series 3 (1966): 176-199.

Cochran, Thomas C. “Did the Civil War Retard Industrialization?” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 48 (1961): 197-210.

Goldin, Claudia, and Frank Lewis. “The Economic Costs of the American Civil War: Estimates and Implications.” Journal of Economic History 35 (1975): 299-326.

Goldin, Claudia, and Frank Lewis. “The Post-Bellum Recovery of the South and the Cost of the Civil War: Comment.” Journal of Economic History 38 (1978): 487-492.

Ransom, Roger L., and Richard Sutch. “Conflicting Visions: The American Civil War as a Revolutionary Conflict.” Research in Economic History 20 (2001).

Ransom, Roger L., and Richard Sutch. One Kind of Freedom: The Economic Consequences of Emancipation. Second edition. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

Gunderson, Gerald. “The Origin of the American Civil War.” Journal of Economic History 34 (1974): 915-950.