Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a significant health concern in the United States, yet reluctance to screen remains high. At the project’s site, there was a need for an evidence-based model that can be implemented to improve screening rates. The purpose of this quantitative quasi-experimental quality improvement project was to determine if or to what degree the implementation of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s System Approach to Tracking and Increasing Screening for Public Health Improvement of Colorectal Cancer (AHRQ’s SATIS-PHI/CRC) toolkit would impact colon cancer screening rates when compared to current practice among patients aged 50-75 in a primary care clinic in urban New York, over four weeks. Hochbaum et al.’s health belief model (HBM) and Rogers’ protection motivation theory (PMT) were the theoretical underpinnings of the project.

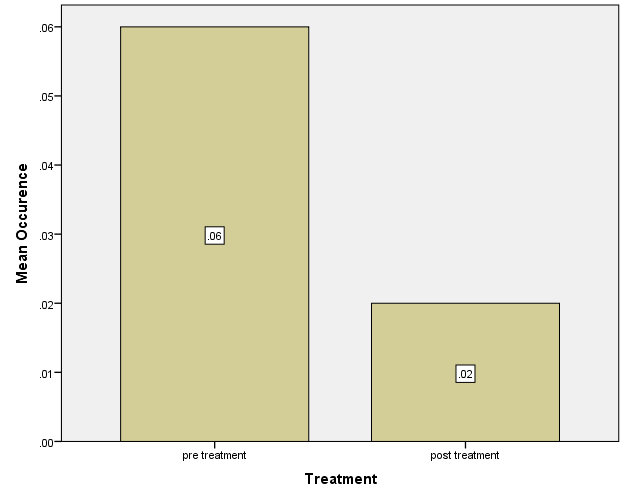

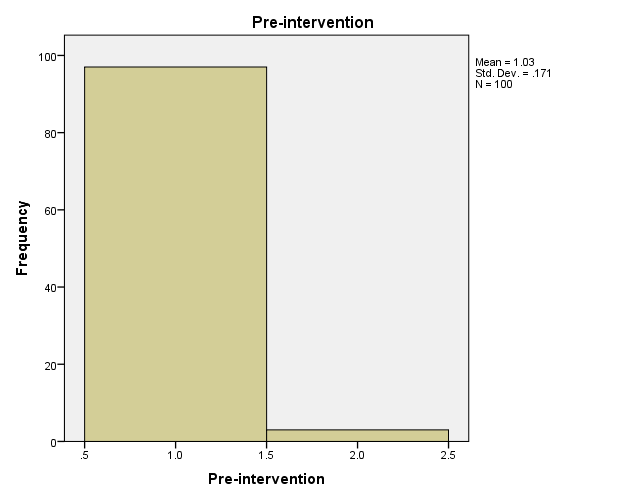

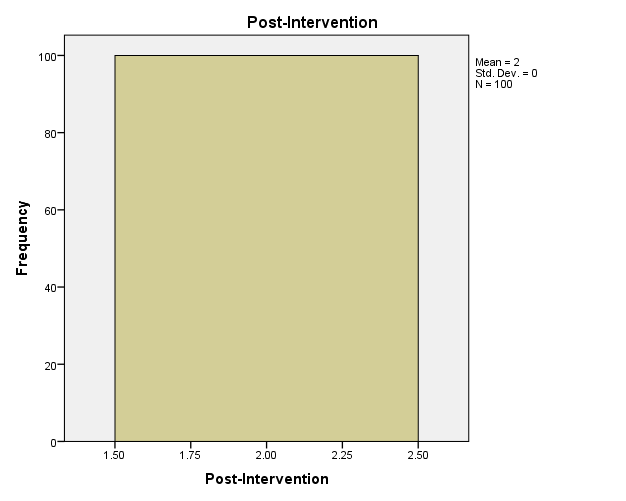

Participants were 100 patients recruited through nonrandomized sampling from an urban Ney York clinic. The CRC screening rates of the sample were obtained from the electronic health record system and analyzed using the Chi-square test. The analysis of the impact of using the SATIS-PHI/CRC toolkit to redesign the screening process showed at X (1) = 88.360, P=.000, suggesting that there was a statistically significant effect of the intervention on screening rate. Further, the project’s results showed that the toolkit improved screening rates, and healthcare facilities should adopt the model. Researchers should conduct further research with larger sample sizes for future projects.

Introduction to the Project

At present, it is not yet determined whether redesigning the colorectal cancer (CRC) screening process can lead to increases in the number of patients undergoing screening compared to the interventions already in place. Even without clarity over the efficacy of early screening for CRC, there have been indications of a downward trend in CRC incidence rates. In particular, between 2013 and 2017, the disease incidence rate declined by1% every year over this period (American Cancer society, 2021a). However, despite the decline in CRC cases between 2013 and 2017, the focus is mainly on older adults. As a result, the true extent of the prevalence of this condition among younger adults is yet to be clearly understood (American Cancer Society, 2021a). When it comes to CRC screening, younger adults may not be receiving sufficient attention.

Older adults are especially vulnerable to CRC. With old age, individuals become susceptible to diseases that can reduce their lifespan. However, adherence to screening guidelines has been lax in the uptake of screening services. In 2010, for instance, only 59% of individuals aged 50 and above for whom screening was recommended had undergone screening (American Cancer Society, 2014). Screening has the potential to prevent CRC as it can detect precancerous growths, such as polyps, in both the colon and the rectum (American Cancer Society, 2014). While most polyps do not become cancerous, the American Cancer Society (2014) advises that the polyps be removed to reduce the chances of CRC (American Cancer Society, 2014).

The essence of early screening is to increase the opportunity for detecting CRC in its initial stages, thereby allowing medical professionals to devise measures to manage the disease. Thus, early screening for CRC is critical toward maintaining the well-being of older adults. It is true that there is already extensive research exploring CRC among older adults. However, the current project is still significant because it sheds further light on the role that CRC screening can play in preventing the development of this condition. More importantly, the project is important because it aimed to establish whether screening conducted using the SATIS-PHI/CRC is an effective intervention for increasing the rate of screening, thereby catching early cases of CRC in some instances while preventing CRC in others.

The purpose of this quantitative quasi-experimental quality improvement project was to determine if or to what degree the implementation of AHRQ’s SATIS-PHI/CRC toolkit would impact colon cancer screening rates when compared to current practice among patients aged 50-75 in a primary care clinic in urban New York over four weeks. Chapter One provides an overview of the introduction to the project and covers topics such as the project’s background, problem statement, the purpose of the project, the clinic question, and advancing scientific knowledge. Other issues that this chapter addresses include the significance of the project, rationale for the methodology, the nature of the project design, definition of terms, assumptions, limitations, and delimitations of the project, and the summary and organization of the remainder of the project.

Background of the Project

Medical screening remains one of the most effective measures to help identify and mitigate disease incidence and or continued progression following the adoption of early interventional measures. Retrospectively, the rate of individuals diagnosed with CRC annually has continued to drop since the mid-1980s (American Cancer Society, 2021a). The reason for this decline was that more people are undergoing screening, after which they adopted healthy behaviors, which have helped reduce their exposure to lifestyle-related diseases like CRC (American Cancer Society, 2021a). Therefore, the uptake of screening services proved sufficient to curtail the spread or rate of occurrence of CRC among the public. Nevertheless, the American Cancer Society (ACS) notes that CRC is the third most diagnosed cancer in women and men in the United States.

Furthermore, the American Cancer Society (2021a, 2021b) estimated that in this year, there are likely to be nearly104, 270 new cases of colon cancer and about 45,230 cases of rectal cancer. Such statistics underscore the need to devise measures that can help curb the spread of CRC. If left unattended, the prevalence of CRC will certainly present significant implications for the entire society. For example, the United States (U.S.) could continue to spend massive amounts every year to treat this condition.

The purpose of this quantitative quasi-experimental quality improvement project was to determine if or to what degree the implementation of AHRQ’s SATIS-PHI/CRC toolkit would impact colon cancer screening rates when compared to current practice among patients aged 50-75 in a primary care clinic, in urban New York, over four weeks. Essentially, the project sought to underscore the role of empirical data in informing the CRC prevention approaches that healthcare institutions put in place. Hence, this project was centered on predetermined criteria which limit participation to individuals aged 50 to 75 years old. The rationale was grounded on the understanding that older adults are highly susceptible to diseases, and preventive interventions like screening are highly recommended to maintain their health (Seematter-Bagnoud & Büla, 2018). Therefore, this project intended to find evidence that expressed the efficacy of early CRC screening using the SATIS-PHI/CRC toolkit in enhancing CRC screening rates.

Problem Statement

The American Cancer Society (ACS) (2021a) emphasizes that colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cause of cancer death in women and men, and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in both women and men when combined in the United States (American Cancer Society, 2021a). The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (2016) previously recommended that adults aged 50–75 undergo CRC screening, with test options including fecal stool blood test yearly, flexible sigmoidoscopy every five years, or a colonoscopy every ten years. However, after the death of Black Panther actor Chadwick Boseman from CRC disease at the age of 42, proponents for early screening lobbied for change (Chiu, 2020). As a result, the USPSTF issued a new guideline on May 18, 2021, which lowered the recommended screening age from 50 to 45.

Today, the recommended age for CRC screening has dropped to 45 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021b). Several scholars have stressed that routine screening and resultant early detection through a range of acceptable strategies (colonoscopy, fecal testing, among others) are helpful and cost-effective in reducing CRC incidence and mortality (Ran et al., 2019). Additionally, the ACS maintains a survival benefit to early detection: five-year survival for localized CRC is around 90%, which drops below 20% for patients diagnosed at late stages (ACS, 2020). Despite this information, screening rates remain relatively low; only 62.4% of age-eligible adults were up-to-date on CRC screening, falling short of national goals for CRC screening between 2000 and 2015 (White et al., 2017).

Further, minority race and ethnicity and socioeconomic challenges such as lack of insurance and low income are associated with higher CRC mortality (White et al., 2017). While there is an abundance of evidence that suggests that early screening saves lives, it is not known if, or to what degree, the implementation of the AHRQ’s SATIS-PHI/CRC toolkit would impact colon cancer screening rates when compared to current practice among patients aged 50-75. This population tends to be fearful of the process; they can better understand and feel confident about the screening procedure with education.

Purpose of the Project

The purpose of this quantitative quasi-experimental quality improvement project was to determine if, or to what degree, the implementation of AHRQ’s SATIS-PHI/CRC toolkit would impact colon cancer screening rates when compared to current practice among patients aged 50-75 in a primary care clinic, in urban New York, over four weeks. A quasi-experimental design was used alongside a quantitative approach to analyze the data. Further, White and Sabarwal (2014) explained that assignment to conditions is based on self-selection or administrator selection in a quasi-experiment. Therefore, this project looked to assess whether there had been any changes in patients’ screening status when comparing their state before and after the intervention. The project focused on patients within the age range of 50 -75 years. It took place in an urban primary care clinic in New York. Based on the clinical question, the variables were identified as the SATIS-PHI/CRC toolkit as the independent variable (IV) and screening rates as the dependent variable (DV). The project was intended to express the importance of preventive measures in fighting diseases.

Clinical Question(s)

The project was grounded on one clinical question: To what degree does the implementation of AHRQ’s SATIS-PHI/CRC toolkit impact colon cancer screening rates compared to current practice among patients aged 50-75 in a primary care clinic in urban New York? Based on the question given and using the AHRQ’s toolkit to redesign the screening process, a quantitative approach was used to determine the efficacy of the SATIS-PHI/CRC toolkit on screening rates within four weeks. The variables are colorectal cancer (CRC) screening using the SATIS-PHI/CRC as the independent variable (IV) and screening rate as the dependent variable (DV). The SATIS-PHI/CRC toolkit was used to guide the screening process.

Advancing Scientific Knowledge

The importance of this project was, in part, to advance the body of scientific knowledge. Currently, it is not yet determined whether early screening for colorectal cancer (CRC) using the SATIS-PHI/CRC toolkit can increase the rate of screening at an urban New York primary care clinic. The project was intended to provide evidence-based results that can be replicated or used to guide the adaption of health interventions when dealing with other diseases in other healthcare facilities, focusing on CRC prevention and treatment. Notably, the lack of evidence accenting the effect of early CRC screening using the SATIS-PHI/CRC on disease incidence highlights a gap within the medical community regarding the promotion of public health. Ebell et al. (2018) explained various barriers to adopting evidence-based medicine when providing treatment and care to patients. Ebell et al. (2018) made an important observation that medical education in the traditional context emphasizes pathophysiologic reasoning as the primary approach to treatment decisions. In the first two years, attention is given to the basic sciences. Such a mentality makes it difficult to adapt and apply new practices studied and proven effective through research.

However, despite the identified barrier, the project was geared toward providing more evidence about the importance of early CRC screening in curbing the spread and occurrence of CRC. The findings can be used to, for instance, help guide care providers when dealing with patients with other health conditions, which can affect the outcome of early CRC screening. Nevertheless, for those that already have mild symptoms of the disease, this project was intended to demonstrate whether, if exposed to early preventive measures, the occurrence of the disease can be studied effectively.

Therefore, this project was intended to add to existing scientific research regarding integrating and applying evidence-based medicine to address varied health problems such as CRC. The health belief model (HBM) is one of the theories that informed the project. The health belief model is a cognitive model extensively used to measure cancer screening beliefs and behaviors. It identifies patterns and barriers to healthy behaviors (Zare et al., 2016). The model was developed in the 1950s by social psychologists Hochbaum, Rosenstock, and others, working in the U.S. Public Health Service to explain the failure of people participating in programs to adopt health promotion solutions (Hochbaum et al., 1952). The model was later extended to study people’s behavioral reactions to health-related circumstances.

Rogers’s protection motivation theory focuses on health and describes one’s attitude and motivation to respond in a self-protective way to a perceived threat to one’s health. This theoretical model helps build self-efficacy and is beneficial in translating knowledge into healthy behaviors and lifestyles (Westcott et al., 2017). Alongside the health belief model discussed above, the protection motivation theory can encourage relevant and appropriate good health screening attitudes and behaviors. For instance, the two models could form the basis of encouraging those aged between 50 and 75 to undergo CRC screening.

Significance of the Project

CRC ranks third among the leading causes of death in America (American Cancer Society, 2021a). As a developed country, the U.S. stands to benefit from the already high-end health solutions at its disposal. For that reason, there is a need to promote the utilization of healthcare services through sensitization of the public regarding the importance of adapting health-seeking behavior. However, the uptake of preventive medicine is, in some cases, hindered because of the attitude and perception of patients. Scholars Alnaif and Alghanim (2009) noted that patients who lack sufficient knowledge about the various ways to safeguard themselves against diseases are unlikely to seek or utilize existing or recommended health services.

Thus, the disease incidence rate is likely to intensify, leading to the economic, social, and personal burdens on the patient and their family; and the healthcare system. Health literacy is a prerequisite to a healthy community. Therefore, there is a need to provide the public with access to necessary preventive medical services. The importance of health literacy explains Alnaif and Alghanim’s (2009) observation that health education is a cornerstone that helps manage chronic diseases such as asthma, obesity, hypertension, cardiovascular heart diseases, and others by providing patients with security and knowledge concerning their health. Through a change in attitude toward the importance of health services, individuals can change their behavior, enhancing their well-being while helping to secure public health. The project sought to demonstrate the efficacy of evidence-based medicine in promoting a healthy population. The results acquired will help guide the implementation of health intervention approaches. For instance, if early CRC screening proves effective, a similar approach can manage other chronic illnesses such as diabetes, asthma, and heart disease.

Rationale for Methodology

For the project, a quantitative approach was adopted. A quantitative methodology makes interpreting data and presenting the findings straightforward and less open to error and subjectivity (Devault, 2019). The structure of quantitative research allows for broader studies, which enables better accuracy when attempting to create generalizations about the subject matter involved (Gaille, 2019). Quantitative analysis utilizes mathematical, statistical, and computational tools to derive results. This structure makes conclusiveness to the investigated purposes as it quantifies problems to understand their prevalence (Gaille, 2019).

Moreover, the quantitative methodology uses homogenous steps to reduce or eliminate bias when collecting and analyzing data. This research approach is particularly advantageous for studies that involve numbers, such as measuring achievement gaps between different groups of patients or assessing the effectiveness of a new intervention (Dowd, 2018). Along with the quantitative method, the project incorporated a quasi-experimental approach to analyze the data acquired.

Nature of the Project Design

The project’s objective was primarily to determine the cause-and-effect relationship between the IV (early CRC screening using the SATIS-PHI/CRC toolkit) and DV (increased CRC screening rates). The project’s design followed a quasi-experimental approach. In support, White and Sabarwal (2014) explained that assignment to conditions is based on self-selection or administrator selection in a quasi-experiment. Therefore, the project looked to allocate participants in one group. The said group received pre and post-implementation education on early colorectal cancer screening using the SATIS-PHI/CRC intervention.

Participants were evaluated four weeks after implementing the said intervention to determine if there were changes in the rate of CRC screening. Because of the nature of the project, the quasi-experimental approach was deemed the best fit. It allowed the principal investigator (PI) to compare pre-implementation data and post-test results to determine the efficacy of the evidenced-based intervention on CRC screening. In part, the effectiveness of an investigation is determined by the validity and reliability of the findings. Additionally, higher external and internal validity justified the use of a quasi-experimental approach which took place in a natural setting. This made it less vulnerable to the manipulative nature of experiments in controlled environments (Reeves et al., 2017).

Compared to other designs, quasi-experimental designs are advantageous because they have a higher external validity as they involve real-world settings instead of artificial laboratory settings (Reeves et al., 2017). Secondly, there is a higher internal validity than non-experimental research because quasi-experimental studies allow the PI to control for confounding variables (Reeves et al., 2017). A confounding variable, such as the existence of co-morbid conditions, might affect the project’s outcome. For example, it could be that there is no change in symptomatology or risk of disease incidence for some patients who undergo early CRC screening because of the existence of another health condition. Here, disease co-morbidity is a confounding variable that is likely to make it difficult to determine the effect of the IV on the DV. Therefore, the quasi-experimental approach is ideal for determining whether early CRC screening will promote positive health outcomes in patients.

In the current case, the PI was able to observe and record the findings without any interference, thereby strengthening the legitimacy and increasing the potential applicability of the results. The sample involved 100 participants who were patients in the urban primary care clinic. At the close of the project, recorded data focused on the screening rates for CRC. In addition, pre and post-intervention data were compared to determine a statistically significant change in CRC screening rates.

Definition of Terms

The Definition of Terms section of Chapter One defined the project’s concepts. In addition, it provided a brief overview of the technical terms, exclusive jargon, concepts, and terminology used within the project’s scope. Terms are defined in layperson terms in the context in which they are used within the project. The following is a glossary of terms that were used recurrently in this project:

Colorectal cancer (CRC)

CRC refers to cancer in the colon or rectum (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020).

Disease Incidence

Disease incidence refers to the occurrence of new cases of disease (CDC, 2012).

Mortality

For this project, mortality refers to death rate or the number of deaths in a certain group of people in a given time period

Rectum

The rectum refers to the passageway that connects the colon to the anus (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021a).

The System Approach to Tracking and Increasing Screening for Public Health Improvement of Colorectal Cancer (SATIS-PHI/CRC) intervention

The SATIS-PHI/CRC toolkit refers to a population-based, system-level redesign of the way CRC screening and follow-up are conducted in a network of primary care practices (for example, in medicine clinics) (AHRQ, 2018a; Harris & Borsky, 2010).

Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS)

HEDIS refers to a comprehensive set of standardized performance measures designed to provide purchasers and consumers with the information they need for a reliable comparison of health plan performance. In addition, HEDIS measures identify opportunities for improvement, monitor the success of quality improvement initiatives, track progress, and provide a set of measurement standards that allow comparison with other plans (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2021).

Assumptions, Limitations, Delimitations

In this project, there are varied assumptions, limitations, and delimitations. The main premise was that this quality improvement project would accurately represent the current problem of low CRC screening rates in the New York hospital’s primary care clinic. For example, due to the current COVID-19 pandemic, patients have not been following up diligently. The hospital has noted the problem and has provided transportation services to transport some patients to and from their appointments and has enlisted the support of social workers and nurses in reaching patients to assess their needs and promote adherence with screening exams and following up appointments.

The SATIS-PHI/CRC intervention tool provides a mechanism for identifying patients eligible for but not up to date in their CRC screening. Additionally, the toolkit provided an avenue for contacting such patients on behalf of their physician’s practice to encourage and administer recommended screening, track screening results, facilitate patient notification, and appropriate follow-up through feedback to providers (Harris & Borsky, 2010).

It was assumed that all health care professionals participating in the implementation of the project would understand the applicability of the model and the benefits to patients and the facility arriving at the best possible outcomes for the patient. The goal was to improve the rates of CRC screening. Providers and other participants received education on how to use the tool. There was enough training to ensure a clear understanding of the tool. The PI addressed all questions and concerns pre-implementation as they arose. According to AHRQ, using academic detailing and performance feedback forms, the toolkit seeks to educate clinical providers, and other staff in participating practices about recommended CRC screening and follow-up procedures (AHRQ, 2018a).

Limitations of a project are any potential weaknesses or restrictions in a project that is primarily out of the investigator’s control and can affect the design and results or outcomes of the investigation (Ross & Bibler Zaidi, 2019). When it comes to limitations, the project was focused on individuals aged 50-75 years. While it is true that patients in this demographic group are most at risk for CRC, by focusing exclusively on this population, the project essentially disregarded younger patients for whom screening is now recommended. The issue here is that it would be rather challenging to apply the findings and conclusions from the project to a younger population, given that one’s age heavily influences their health outcomes.

For instance, younger adults are more vibrant and can engage in vigorous activities, which might undermine the ability to detect symptoms of CRC compared to older adults. However, to account for the effect of the limitations, the project was meant to increase knowledge regarding ways to improve screening rates and manage the spread and occurrence of CRC among the measured population. In doing so, the PI was able to find specific information that applied to the chosen targeted population.

Delimitations are the definitions one sets as the boundaries or limits of their project to so that the aims and objectives do not necome impossible to achieve. Delimitations are mainly concerned with the study’s theoretical background, objectives, research questions, variables under study and study sample (Thefanidis & Fountouki, 2019). The project was delimited to individuals who met all the criteria of the project. Therefore, individuals at risk for CRC and not at the required age were not selected as part of the population. Another delimitation for the project was that the participants were delimited to only one New York hospital primary care clinic, which accounts for just one city hospital in New York. However, 11 hospitals and multiple primary care clinics in the network face similar problems with CRC screening.

For example, two hospitals and their clinics work closely with the gastroenterologists practicing collaboratively and alternating days at both facilities. However, the patients seen in one hospital are not automatically seen in the other unless there is a referral from one physician or provider to the next. The providers go in both places, but the patients have to stay in one location, whichever one they choose. Therefore, the investigation findings can be generalized, and the project’s results can be applied to both facilities. Both facilities have a similar makeup of patients with identical poor or low screening rates problems.

Summary and Organization of the Remainder of the Project

The significance of CRC screening for adults aged 50 to 75 years has been well recognized and primarily accepted by the medical community. The American Cancer Society (ACS) emphasized that CRC is the third most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States (ACS, 2017). In 2017, the agency reported an estimated 95,520 new cases of colon cancer and 39,910 cases of rectal cancer diagnosed in the United States (ACS, 2017). The ACS projected that CRC would cause about 52,980 deaths during 2021 (ACS, 2021b). Despite the benefits of early cancer detection and the availability of practical screening tests, rates of CRC screening remain low (Modica et al., 2019). According to the ACS, in 2010, only 59% of those eligible for CRC screening received a screening test (ACS, 2014). Scholars stressed that routine screening and resultant early detection through a range of acceptable strategies (colonoscopy, fecal testing, among other test) are helpful and cost-effective in reducing CRC incidence and mortality (Ran et al., 2019).

Thus far, a review of the project’s background was provided, along with the clinical question upon which the project was grounded. A look at the background information highlighted the lack of evidence in determining the efficacy of early CRC using the SATIS-PHI/CRC toolkit on CRC screening rates. While the project focused on adults in the 50-75 age groups, it was intended to provide evidence that could be replicated and applied in other settings. In the next chapter, a discussion of existing literature on the medical issue at hand is provided. Theoretical frameworks are also highlighted to help offer a link between the project’s purpose, the health behavior of patients, and recommendations to promote a healthier community. Chapter Two covers development of the topic, explication of the problem, the clinical questions, and a discussion of the project design elements. Chapter Three provides an outline of the methodology that was used for the project. The chapter explored data collection and analysis, the project participants, and the measures taken to ensure that the DPI project complied fully with applicable ethical requirements. Chapter Four discussed the data analysis procedures, the results that the investigator obtained, the sample characteristics, and the observations regarding the impact of CRC screening. Chapter Five concluded the project with a comprehensive summary, summary of the findings, conclusions, recommendations for the project, and recommendations for future practice.

Literature Review

As is evident this far, the purpose of this quantitative quasi-experimental quality improvement project was to determine if or to what degree the implementation of AHRQ’s SATIS-PHI/CRC would impact colon cancer screening rates when compared to current practice among patients aged 50-75 in a primary care clinic in urban New York over four weeks. Already, there exists a tremendous amount of literature that explores various components of the project’s guiding clinical question. For example, investigators have already established that individuals in the 50-75 age group are among the populations that face the greatest risk of developing CRC (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2021). Therefore, the purpose of this chapter was to shed light on the findings and insights from past research undertaken.

An organizational framework was adapted for this chapter. The chapter began with an outline of the theoretical foundations that underlie the project to set the stage. Next, the focus was given to the different theories and models that explained how using the SATIS-PHI/CRC toolkit to redesign the screening process can increase CRC screening rates. Next, the chapter explored some key themes and questions that have emerged from existing literature. Among the specific issues that this section addressed included the impact of the SATIS-PHI/CRC toolkit on CRC screening rates. The chapter concluded with a summary highlighting the most important results obtained from the literature review.

In conducting the literature review, caution was exercised to ensure a rigorous and extensive analysis was done. The PI conducted an in-depth examination of relevant literature. The critical measures adapted included providing that all the articles considered were published within the last five years, had been peer-reviewed, and addressed issues related directly to the clinical question for this project. Additionally, databases Pub Med, Ebscohost, CINAHL, and Google Scholar were used to find publications. These databases are appropriate because of their massive volume of collections and the valuable search tools that they incorporate to streamline finding literature.

Moreover, as part of the literature review, the principal investigator used keywords as colorectal cancer, colorectal cancer screening benefits, disparities, and colorectal cancer screening rates. These keywords yielded relevant results. Furthermore, only articles for which full texts were available were considered for inclusion in the review.

There is a gap in CRC screening. As numerous scholars have determined, despite CRC’s screening clear benefits, its uptake among patients has been low (Brenner & Chen, 2018). For example, Brenner and Chen (2018) noted that the administration of CRC screening falls short of expectation across many countries, given the proven advantages that screening offers. Huang and Huang (2017) also established that CRC screening rates are unacceptably minimal. If the U.S. is to make meaningful progress in its prevention of CRC, then it should be doing more aggressive screening promotions. The history of the slow adoption of CRC screening in the U.S. is long and complex. This history can be traced back to the early 2000s, when such organizations as the ACS began to issue guidelines to be used by practitioners in their screening procedures (Smith et al., 2019).

As Smith et al. (2019) reported, CRC is among the cancers that received early attention from the ACS, which issued regular updates and led an aggressive campaign to persuade patients to embrace screening. New and innovative solutions such as colonoscopy have been developed to improve CRC screening in the succeeding years. However, many Americans are still reluctant to undergo screening, resulting in an increased risk of developing the condition (Honein-AbouHaidar et al., 2016). Different stakeholders have historically disagreed on the best screening protocols, and tests for CRC are among the factors that experts have identified as responsible for the low screening rates in the U.S (Ransohoff & Sox, 2016).

Furthermore, the U.S. legal system is so convoluted and complex that practitioners and healthcare organizations have struggled to align screening procedures with applicable law, leading to a decline in screening rates (Ransohoff & Sox, 2016). Essentially, in addition to resistance from patients, the failure of CRC screening in the U.S. is also an outcome of regulatory and legal challenges that undermine the capacity of healthcare providers to perform screening. Throughout the literature and listed in this chapter are themes and subthemes identified as presenting barriers to CRC screening. The themes identified are CRC incidence and impacts, CRC risk factors and resource utilization, and colorectal cancer screening. The chapter provided a more detailed overview of the themes and subthemes identified.

Theoretical Foundations

Using the AHRQ’S SATIS-PHI/CRC toolkit to redesign the CRC screening process was the intervention that the current project examined to establish whether this solution can impact the CRC screening rate. The project was founded on the health belief model and the protection motivation theory. At their core, these theories underscore the need for comprehensive solutions to promote specific health behaviors and impact the design of disease prevention initiatives. The philosophy that will shape the project is the belief that screening allows for prevention and the early detection of illnesses. According to Lor et al. (2017), screening is generally effective because it provides healthcare practitioners early detection tools to fight diseases. Once a medical condition is in the early stages of development, appropriate measures can be instituted to keep the disease from further progressing, thereby preventing severe illnesses and, in some cases, death.

The successes that nations like the U.S. are witnessing in their war against different cancers result from timely age-appropriate screening (White et al., 2019; Yuan et al., 2018). It was hoped that when SATIS-PHI/CRC screening is rolled out at the New York hospital primary care clinic, it will generate diagnostic information that makes it possible for this facility to devise prevention and treatment solutions to increase screening and keep incidence rates of the condition at a low rate.

As previously mentioned, the project was founded on the health belief model and the protection motivation theory. Established by Ronald Rogers in the 1970s, the basic premise of protection motivation theory is that individuals tend to act in self-preserving ways. Essentially, Rogers believed that individuals would seek to eliminate risk or danger and restore their safety when confronted with a risk or danger (Jones et al., 2015; Rogers, 1975). Protection motivation theory identifies the severity of a threat, the probability of its occurrence, the mitigation measures available to an individual, and the individual’s capacity to activate these measures as among the key determinants of actions or behaviors that individuals institute to protect themselves (Westcott et al., 2017). Protection motivation theory presents several important implications with the present project:

- It suggested that driven by fear of developing CRC; patients will likely seek screening tests. Fear of getting the disease can promote protective behaviors and explain one’s cognition against threat and other coping behaviors.

- Since the participants in the project are aged between 50 and 75, the likelihood of developing CRC is significant. The high incidence of colorectal cancer can largely be prevented by adherence to routine preventive screening.

- This theory indicates that screening is a widely available and affordable solution that offers real protection against the condition. Therefore, the protection motivation theory can effectively identify successful health behavioral processes and interventions in encouraging, promoting, and getting patients to adhere to protective health behavioral practices. This argument makes the protection motivation theory valid and insightful in supporting and guiding the project.

Various researchers have used the protection motivation theory outlined above to understand populations’ health behaviors. For example, guided by this model, Khodaveisi et al. (2017) conducted a study to establish the effectiveness of a nutritional program designed for obese women. They determined that the program encouraged women to adopt healthier eating habits and concluded that the protection motivation theory accurately explains how individuals make decisions regarding their health. Basically, as Khodaveisi et al. (2017) determined, patients’ health choices are informed by the various factors that constitute the protection motivation theory. Furthermore, Aqtam and Darawwad (2018) confirmed that this theory is valuable for healthcare. After undertaking a literature review, they noted that the protection motivation theory also underlies the health promotion and disease prevention intervention that nurses design to influence research. Therefore, previous research has concluded that the model improves outcomes when incorporated into healthcare programs.

The health belief model is yet another theory whose elements are reflected in the project. Essentially, the health belief model posits that their belief determines an individual’s behavior toward a threat and their view on the effectiveness of available remedies. When individuals perceive the danger as significant and that the solution is effective, the health belief model suggests they are likely to implement it (Rakhshanderou et al., 2020). Moreover, the health belief model also recognizes that perceived barriers undermine the adaption of interventions. In contrast, self-efficacy provides individuals with the drive to undertake measures to limit their exposure to illness. This theory was devised in the 1950s by Godfrey Hochbaum, Irwin Rosenstock, and a group of scholars who sought to create a model that would account for the various factors that influence individual health behaviors (Rakhshanderou et al., 2020). In an insightful article that explored this theory and its implications for the design of healthcare programs, Rosenstock (1974) reiterated that individuals’ beliefs play a role in impacting their utilization of health resources.

The health belief model is important for the present project. First, the model underscores the need to ensure that patients believe that CRC is a real threat to their health and that screening is a simple, widely-available yet highly effective intervention that reduces the incidence and mortality of CRC over time. Second, the health belief model posits that when messages are delivered that target barriers to preventive care while focusing on self-advocacy and self-care self-efficacy, optimal successful behavioral change will occur. The health belief model and protection motivation theory are essential models of health behaviors and can influence or motivate an individual to care for oneself; for example, engaging in health promotional behaviors and preventing disease processes.

As with the protection motivation theory, the health belief model has also been validated in previous research. For example, Loke et al. (2015) used this model to examine the specific factors that influence pregnant women’s decisions regarding how to deliver. According to these scholars, the women’s decisions consider factors like perceived benefits, risks, and severity of the different delivery methods when making the decision. For example, during their study, Loke et al. (2015) noted that some women were worried about the risk of vaginal tearing that accompanies natural births and therefore opted for caesarian delivery. In addition, Siddiqui et al. (2016) also relied on the health belief model to investigate how households in Karachi, Pakistan incorporate healthy behaviors into their lifestyles. These scholars’ main observation was that self-efficacy and threat perception are among the key factors that underlie this population’s health decisions. Therefore, previous research has confirmed that the health belief model properly accounts for the behaviors and decisions that individuals and entire populations make.

The implementation of the project required supportive policies, systems, beliefs, and processes. For example, for the patients to agree to undergo screening, they must believe that screening is safe and effective and should be provided with services that streamline the screening process. After being screened, patients should get their results right away. Those diagnosed with CRC should then follow the steps for treatment and start right away. On the other hand, for patients free of CRC, appropriate education and support must be provided to protect them against the condition. With the treatment and preventive measures in place, the hope was for the New York hospital primary care clinic to report a significant increase in CRC screening rates.

Review of the Literature

Already, scholars have shed light on various aspects of CRC and the role of screening in preventing and lowering the number of patients who die prematurely from this condition. The following section examines some key issues that emerged from the literature and their relevance to the current project. The focus of this section is to demonstrate that CRC is already receiving considerable attention. However, as the discussion below reveals, some gaps can be addressed through additional research and scholarship.

CRC Incidence and Impacts

The incidence and effects of CRC are among the themes explored in the literature review. These issues are important because they help highlight the need for and the project’s significance. For example, as will be made clear below, CRC incidence has been on the rise in the U.S., and this condition is to be blamed for poor health and worse financial outcomes among patients. These negative impacts highlight the tremendous value that the project will add to healthcare.

Statistics

To understand the need for the current project, it is helpful to consider the scale of the CRC problem. CRC is well established as among the most pressing healthcare challenges confronting the U.S. today (Rawla et al., 2019). Existing research has warned about the alarming increase in the number of new CRC cases being diagnosed in the U.S. and other countries. Siegel et al. (2020) are among the scholars who have shed light on the incidence of this condition among Americans. Their text noted that in 2020, more than 147,000 new cases of CRC were reported in the U.S. In providing these epidemiological figures, Siegel et al. (2020) conducted a quantitative study.

They performed a rigorous analysis of data collected as part of a surveillance program developed by the National Cancer Institute. Siegel et al. (2020) also report that in 2020, the U.S. recorded at least 53,200 CRC-related deaths. Abualkhair et al. (2020) also confirmed that the incidence rates in the U.S. are worryingly high. Unlike Siegel et al. (2020), whose study focused on the general American population, Abualkhair et al. (2020) gave particular attention to those aged 40 and 49. As part of their cross-sectional quantitative study, the researchers reviewed surveillance data between 2000 and 2015 and determined that since adults in the 40-49 age groups are not prioritized for screening, many cases of CRC within this population go undiagnosed (Abualkhair et al., 2020). These findings undoubtedly indicate that CRC remains prevalent across different age groups in the U.S. and that urgent intervention is desperately needed.

Other regions have also received some attention from researchers who have sought to establish the global incidence rates of CRC. For example, Sierra and Forman (2016) joined forces to determine the burden of this condition on such Central and South American nations as Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay. The quantitative study that Sierra and Forman (2016) conducted led them to find that despite the screening guidelines and protocols that these nations have in place, cases of CRC have been on an incline, thereby imposing strains on fragile healthcare systems that are already overburdened. To explain the increasing prevalence of CRC in South and Central America, Sierra and Forman (2016) noted that in this region, other health problems such as obesity, cigarette smoking, and poor nutrition could be responsible for the spike in CRC incidence.

This observation is important as it underscores the role that health behaviors play in influencing the prevalence of CRC. The present project sought to shed light on how such interpersonal issues as individual health behaviors affect exposure to CRC and the need to modify these behaviors to promote early CRC screening to reduce disease incidence. Other scholars have also conducted quantitative studies and confirmed that while the U.S. is among the nations with the highest rates of CRC, this condition is a global challenge that has spared no country (Arnold et al., 2017; Keum & Giovannucci, 2019). The worldwide spread of CRC means that the current project will yield insights that the project’s site, other U.S. facilities, and countries globally can adapt to harness the power of screening in their efforts to curb CRC.

The impacts of CRC have been devastating. Generating adverse health outcomes is among the effects that this condition is known to have. Reducing the quality of life of patients is one of the ways that CRC negatively affects human health. There appears to be a consensus among scholars and experts that even when patients recover fully from this condition, they struggle to restore their quality of life. For example, Ratjen et al. (2018) established the association between CRC and health-related quality of life (HRQOL).

Their study engaged 1294 individuals who had recovered from CRC and used the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 to determine how this condition had affected the participants’ lives. In addition to finding out that 175 of the patients enrolled in the study had died during the research, Ratjen et al. (2018) also noted that such issues as the decline in cognitive functioning were alarmingly common among the surviving participants. This observation led Ratjen et al. (2018) to conclude that CRC robs patients of their dignity, and this may lead to the cause of premature deaths in affected patients. This conclusion echoed the findings that Mrabti et al. (2016) obtained after investigating the health outcomes of CRC among a group of patients whose median age they calculated at 56 years. In this multicenter cohort qualitative study, Mrabti et al. (2016) were driven to determine the symptoms and quality of life issues among patients with CRC. They found that while such interventions as radiotherapy vastly improved symptoms, the patients experienced hardships that ranged from impaired physical and cognitive function to reduced role and social functioning (Mrabti et al., 2016). Essentially, CRC adversely impacted all areas of the lives of these patients

CRC Impacts

Imposing an economic burden on patients, families, and communities is another negative outcome of CRC. Numerous scholars have observed with great concern that individuals diagnosed with CRC incur huge costs as they seek treatment. Mariotto et al. (2020) have led the research community in warning about the economic impact of CRC treatment. The purpose of the quantitative study that they performed was to compute the average Medicare claims for CRC patients between 2007 and 2013 (Mariotto et al., 2020). They determined that initially, costs were $56,000 but can rise as high as $92,500 for patients requiring end-of-life care. Furthermore, Mariotto et al. (2020) determined that the treatment costs are highest among non-white and younger patients diagnosed with the advanced form of CRC. Those who had a history of cancer incurred even greater expenses. Blum-Barnett et al. (2019) joined Mariotto et al. (2020) in acknowledging that for many patients with CRC, the cost of treatment is prohibitively high.

For their qualitative semi-structured study, Blum-Barnett et al. (2019) held discussions with 14 individuals who had survived early-onset CRC. The main aim that these researchers sought to accomplish was to shed light on the impacts that CRC has had on the financial burden and health and the quality of life of these patients. They found that in addition to straining the patients’ finances, CRC had also resulted in emotional distress, harmed personal relationships, and reduced their quality of life. These adverse impacts highlighted the need for screening, a preventive measure that could hold the key to preventing the development of CRC and death. Others argued that all tests aren’t priced equally, and stool tests are just as effective as getting a colonoscopy to detect cancer when used according to recommended schedules. For example, although all screening methods are covered by insurance, in 2020, Medicare paid $16 for FIT and $509 for the Cologuard test (Jaklevic, 2021). A colonoscopy cost much more (Jaklevic, 2021). While all arguments on CRC impacts are reasonably stated, there needs to be some standardization about the consensus of CRC impacts and type of tests.

Prevention Interventions

Tremendous progress has been made in developing solutions for the prevention of CRC. Gonzalez et al. (2017) undertook an examination of some measures known to protect individuals and even entire communities against developing CRC. Their study took the form of a literature review and established that smoking cessation, nutritional counseling, and screening are among the interventions that significantly reduce CRC risk. Other researchers have confirmed that these prevention strategies are indeed effective. For example, following an extensive review of the outcomes and approaches to preventing CRC, Hull et al. (2020) identify smoking cessation programs as among the measures that have shielded populations against CRC and even improved recovery for those already diagnosed with the condition. Amitay et al. (2020) and Wilkins et al. (2018) also observed that when individuals quit smoking and adopt healthier lifestyles, their risk of CRC drops significantly.

The fact that there are numerous solutions known to offer protection raises questions about why the incidence of CRC within the American and global populations remains high. The current project presented screening as an approach that could persuade patients to take a keener interest in their health and become more involved in the efforts to contain CRC. Unlike the USPSTF, the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC) does not recommend using colonoscopy as a primary screening test for colorectal cancer due to lack of evidence of its importance. Instead, it advises for adults between 60 and 74 years of age, screening for colorectal cancer every two years using Fecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT), (either FOBT with a guaiac smear method (gFOBT), or Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) or every ten years using flexible sigmoidoscopy (Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, 2016). For adults aged 50 to 59, the CTFPHC provided a weak recommendation for screening every two years using Fecal Occult Blood Test (FOBT), (either FOBT with a guaiac smear method (gFOBT), or Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT) or every ten years using flexible sigmoidoscopy (Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC), 2016).

While most CRC prevention strategies in use today are conventional, complementary and alternative solutions are rapidly emerging. Medicinal plants are among the remedies that are believed to protect against CRC. Aiello et al. (2019) assessed whether these plants offer real benefits and are indeed safe. These researchers focused attention on seeds, leaves, fruits, and plant roots often included in alternative therapies.

They established that in addition to being safe, the medicinal plants offer some relief and could effectively treat CRC. However, they also clarified that since the study was conducted in a laboratory, it was difficult to conclude that these benefits would be witnessed in a clinical trial. Huang et al. (2019) also conducted a mechanistic review to examine how the compounds found in medicinal plants function to prevent and treat CRC. They established that these plants can be beneficial and proposed that drugs for CRC treatment be comprised of elements derived from medicinal plants. However, as is the case with the study carried out by Aiello et al. (2019), this study has the shortcoming of being done in a lab. Further studies involving human participants are needed to establish whether plants and other forms of alternative and complementary medicine reduce exposure to CRC and help to extend the lives of those living with this condition.

While the risk of getting CRC may be high in some patient populations based on their family history, and there are many different modalities to testing, some individuals are reluctant to perform CRC-related testing due to fear. In addition, opponents argued that any abnormal results from tests other than a colonoscopy necessitate a colonoscopy to evaluate the abnormal test result. Again, this may lead to fear of testing and rejection, as most harms of screening for CRC are related to colonoscopy, including perforation (Doubeni, 2021).

CRC Risk Factors and Resource Utilization

In addition to the incidence and impacts of CRC, the literature review also highlighted the risk factors and the disparities in resource utilization among different populations. According to the literature, insufficient knowledge plays a vital role in any obstacles that limit access to care. Therefore, these subjects were explored to identify the most vulnerable groups most likely to benefit from the project.

Poverty

There is ample evidence that individuals from socioeconomically disadvantaged communities and backgrounds account for a disproportionate number of people living with CRC. Among the scholars who have warned that poverty poses a real danger to America’s campaign to reduce CRC incidence is Boscoe et al. (2014), who collaborated to investigate the relationship between the prevalence of CRC and poverty. Relying primarily on diagnostic data collected between 2005 and 2009 in Los Angeles, Boscoe et al. (2014) confirmed that being poor means that one is significantly more likely to become ill with CRC. In a study conducted in conjunction with the CDC, Kollman and Sobotka (2018) also set out to shed light on whether and how poverty contributes to the incidence and adverse outcomes of CRC.

Their study compared CRC rates in poor and affluent areas in Ohio. Through quantitative research, Kollman and Sobotka (2018) reached the same conclusion that Boscoe et al. (2014) arrived. They found that the incidence rate of all cancers, including CRC, was at least 19% higher among the poorer counties than in the wealthier neighborhoods. Many other researchers have made similar observations and called for the development of solutions targeted at poor communities (O’Connor et al., 2018; Tanaka et al., 2020). The question of poverty is relevant to the present project because it evaluates a low-cost intervention and can be modified to suit the unique needs and the barriers that poor patients encounter as they seek to utilize healthcare resources.

The impact of poverty on CRC rates can be seen when one compares the situation in different countries. As Arnold et al. (2017) found out, an alarming increase in CRC incidence has been observed among low and middle-income countries in the recent past. On the other hand, in industrialized nations, the prevalence of CRC is dropping or stabilizing. Schleimann et al. (2020) concurred with Arnold et al. (2017) that today, poor communities are bearing the brunt of CRC. In addition to finding that low and middle-income nations accounted for an increased proportion of CRC cases, Schleimann et al. (2020) also reported that in poorer countries, survival rates for those who develop CRC are depressingly slim due to fragile and inadequately-funded healthcare systems. Abotaleb (2018) also found that communities in developing countries are more susceptible to developing this cancer due to a lack of investment in CRC prevention measures.

Furthermore, according to Abotaleb (2018), in such developing countries as Egypt, the cost of CRC treatment is unaffordable for many, and it is therefore not surprising that underdeveloped nations lead the world in CRC prevalence. Moreover, the impact of poverty is so significant that, as Wise (2016) noted, children who grow up in poor neighborhoods are more likely to develop CRC. Thus, it is clear that for efforts to curb CRC to yield positive results, attention must be shifted toward addressing the socioeconomic determinants of health.

In addition to identifying poverty as among the risk factors for CRC, existing research has outlined the specific mechanisms through which poverty fuels CRC incidence and mortality. Among the scholars who have established the link between poverty and CRC risk are; Syriopoulou et al. (2019), who undertook a population-based study involving 470,000 participants from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds and diagnosed with CRC. According to Syriopoulou et al. (2019), poorer patients face the worst prospects of recovery and the most significant risk of developing CRC because of under-investment in their communities. Henry et al. (2014) note that the direction of the association varied globally and argued that while it has been reported that CRC and subsite-specific incidence rates vary by socioeconomic status (SES), in the USA and Canada, lower SES has been associated with a higher risk of CRC. In contrast, in Europe, Australia, and South Korea, lower SES has been associated with a lower risk of CRC (Henry et al., 2014).

The authors further commented that, while SES is not a direct determinant of the incidence differences by subset, variance in incidence rates among SES groups is likely due to common CRC risk factors, which vary by SES. Such factors as physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, smoking, obesity, and poor access to and underuse of screening services for early detection and removal of precancerous polyps are determinants noted (Henry et al., 2014). Essentially, these scholars blame governments for failing to prioritize the well-being of poor populations. The fact that poverty reduces access to such resources like parks and gyms, as well as good nutrition that is needed to prevent and treat CRC, also helps to explain why the poor account for the majority of CRC cases and deaths (Jackson et al., 2016; Rock et al., 2020).

The project accounts for poverty’s role in CRC incidence. Coughlin (2020) carried out a systematic review and concluded, to address social determinants of colorectal cancer, effective interventions are needed that account for the social contexts in which patients live. The review also explains that colorectal cancer incidence rates are positively associated with income and other measures of socioeconomic status. In contrast, low socioeconomic status tends to be associated with poorer survival (Coughlin, 2020). While it does not mainly target poor communities, this project recognizes the hardships these groups face and steps needed to ensure that no participant encounters any unnecessary obstacles while attempting to undergo screening for CRC. Since the start of the project, the project’s site has begun working with its patients to find ways to improve ease in scheduling and getting them to the facility on their test date.

Role of Geography

Geography is another risk factor for CRC. Generally, individuals in rural areas face a higher risk of becoming sick with CRC when compared to their counterparts in more developed urban centers. This is one of the main observations that Rogers et al. (2020) made after undertaking a population study involving 4,660 men drawn from various areas in Utah. In addition to finding that the patients from rural Utah were more likely to have CRC, Rogers et al. (2020) also established that these patients had lower survival rates. This finding is essentially in line with the study outcomes that Carmichael et al. (2020) performed. The purpose of this quantitative quasi-experimental quality improvement project was to determine if or to what degree the implementation of AHRQ’s SATIS-PHI/CRC toolkit would impact colon cancer screening rates when compared to current practice among adults aged 50-75 in a primary care clinic in urban New York, over four weeks. One of the results that Carmichael et al. (2020) obtained was that the prevalence of CRC in rural areas was higher than in urban regions.

However, they also found that when they undergo screening, patients in the rural regions significantly reduce their CRC risk, thereby helping to eliminate the regional disparities. Other researchers have echoed this finding and have endorsed screening as a safe, cost-effective, and highly impactful approach to lowering inequalities and improving health (Alyabsi et al., 2020; Swaminathan et al., 2020). The hope was that the present project would add to the existing body of knowledge that explored the solutions that can be implemented to ensure that communities in rural areas enjoy the same level of access to preventative resources and treatment options available to their counterparts in urban centers.

This project aimed to achieve this by ensuring that the participants involved in the project are from different ethnic groups and reflect the demographic and regional diversity of the U.S. Scholars have attempted to shed light on the mechanisms that underlie the regional disparities in CRC prevalence and mortality. Among the factors that have been blamed for the differences between rural and urban areas is the under-investment in rural regions. For example, Alyabsi et al. (2020) performed a retrospective cohort study to establish the amount of time patients from rural and urban areas spend traveling to their practitioners to undergo CRC screening. They noted that, on average, those from rural regions were forced to travel long distances as their immediate communities lacked screening programs. To explain this finding, Alyabsi et al. (2020) suggest that the U.S. has failed to invest in healthcare infrastructure designed to serve rural populations adequately. Zahnd et al. (2021) also explained why rural areas continue to lag behind their urban counterparts.

According to Zahnd et al. (2021), it is crucial to consider race and ethnicity’s role in America’s healthcare policy to understand the disparities fully. Zahnd et al. (2021) conducted an extensive data analysis to determine how age mediates CRC incidence in rural and urban regions. They found that while rural areas generally fall behind in CRC incidence, rural regions with the majority of Native American populations had some of the highest CRC prevalence rates that they recorded. This result is significant as it indicates that if the U.S. is to make any meaningful gains in increasing CRC screening and reducing CRC incidence, it must pursue racial justice and strive to eliminate disparities. In a 2017 article on a discussion on rural communities and colorectal cancer screening, Dr. Djenaba Joseph, medical director of CDC’s Colorectal Cancer Control Program, admitted that screening rates are lower in rural areas, where geography causes barriers like lack of access to providers and lack of specialists or access to those specialists (Miller, 2017). However, she suggested that when providers engage their age-appropriate patients and talk to them at every opportunity about colon cancer screening, rates of screening increase (Miller, 2017).

According to the article, Joseph further emphasized that knowledge about available resources helps providers and patients decide on the best CRC screening test. Dr. Joseph also pointed out that evidence-based interventions such as reminders work well in rural areas and can help small communities improve screening rates. For patients, who often deal with acute health problems or multiple chronic problems, she suggested reminders as valuable tools for patients and chart reminders prompt for providers (Miller, 2017). The current project is among the resources that the nation can leverage to establish a new dispensation where all Americans enjoy unhampered access to such services as screening. Being established on such theory as the health belief model, the project demonstrated that when they encounter barriers like limited access to screening services, patients are less likely to sign up for CRC screening without education.

Health literacy

Health literacy is yet another factor that is known to influence CRC outcomes. Essentially, health literacy is concerned with individuals’ capacity to locate, dissect and apply health information. For best health outcomes, patient populations must be health literate (McDonald & Shenkman, 2018; Singh & Aiken, 2017). Health literacy has emerged as a resource that plays a crucial role in protecting populations against colorectal cancer and improving the survival of patients who already have the condition. Arnold et al. (2019) performed a randomized controlled trial that concluded that health literacy is an essential component of programs for curbing CRC. Working with a group of patients aged between 50 and 74 from four rural communities in the US, Arnold et al. (2019) sought to establish whether such techniques for enhancing health literacy as the use of pamphlets containing information on CRC and the teach-back approach have any impact on CRC screening.

As one would expect, Arnold et al. (2019) found that these strategies were highly effective as they encouraged the participants to seek screening and other CRC-related health services. Conversely, low levels of health literacy have been shown to increase the risk of developing CRC. For instance, Woudstra et al. (2019) found that patients who lack adequate health literacy skills are often unable to take advantage of the various programs and services developed to protect them against CRC. Furthermore, without these competencies, patients are usually unaware of these services, and when they understand that the programs exist, they lack the knowledge regarding how to access them.

Horshauge et al. (2020), Mantwill et al. (2015), and Stormacq et al. (2019) pointed out that the concept of health literacy is of particular interest as health literacy has been suggested as a potentially modifiable factor by which health disparities, such as inequalities in CRC screening, can potentially be reduced (Horshauge et al., 2020; Mantwill et al., 2015; Stormacq et al., 2019). However, others added that literature regarding the association between health literacy and CRC screening uptake is inconsistent. Some studies concluded that inadequate/limited health literacy is associated with lower screening uptake (Horshauge et al., 2020; Solmi et al., 2015), whereas other studies find no association (Miller et al., 2007; Wangmar et al., 2018). The current project recognized the importance of health literacy. Among the key components of the project was patient education. As part of the education packet for the project, all participants were provided with information on the benefits of screening. Furthermore, by highlighting the value of patient education, this project provided healthcare providers and policymakers with the evidence needed to incorporate health literacy programs into their efforts to tackle CRC.

Colorectal Cancer Screening

The third theme that emerged from the literature concerns CRC screening. During the literature review, it became evident that scholars agreed that when administered early, screening can indeed insulate populations against CRC and vastly improve survival outcomes when diagnosed. Therefore, examining the role of screening is deemed important to establish the value of the present project.

Current State of Screening

The current state of CRC screening is one of the numerous sub-themes upon which scholars have paid particular attention. Evidence suggests that many patients who are eligible for CRC screening have not undergone this procedure. For example, in 2016, only 68.8% of adults in the 50-75-year age group had been screened for CRC, according to a CDC report (CDC, 2020). This figure represents a 1.4% increase from the previous year. However, even as the U.S. celebrates the progress that it is making in persuading its citizens to undergo screening, it is recognized that millions remain susceptible to CRC because they are yet to be screened.

Various factors are behind the gains that the U.S. has made in increasing the acceptance and use of screening services among its patients. In their report on screening rates in the country, Montminy et al. (2019) commended the U.S. for the valiant and unrelenting commitment that it has demonstrated. These scholars note that enabling legislation that has facilitated access to screening programs and the development of non-invasive screening protocols are interventions that have fueled the increase in the number of Americans agreeing to this procedure. The measures that the U.S. has instituted demonstrate that it is dedicated to fighting CRC.

As the discussion above has shown, CRC screening rates in the U.S. are on the rise. However, it should be noted that there are certain areas where the U.S. is performing poorly. For example, the nation has been unable to ensure that all its citizens enjoy access to screening services. As White and Itzkowitz (2020) observed, racial minorities have some of the lowest screening rates in the US. A previous section pointed out that in many minority neighborhoods, healthcare services are in short supply. Therefore, it is not surprising that minorities in the U.S. are less likely to take advantage of screening programs.

Moreover, historical injustices that some of these communities have endured have harmed their confidence and trust in the medical community. For example, according to Taylor (2019), the slow uptake of medical programs among African Americans can partly be blamed on racism and inequality. Unless the U.S. assures this population that screening is safe and helps save lives, African Americans and other minorities will continue to reject this procedure. The present project addresses the concerns these groups have raised by ensuring that all communities are fairly represented, and that the insights generated by the project are used to improve access to screening services across the country.

Screening Challenges

As it attempts to make CRC screening available to all, the U.S. has encountered several challenges. DeGroff et al. (2018) highlighted some hardships that have frustrated efforts to screen the most vulnerable populations. In their discussion on measures that the nation can institute to improve screening rates, DeGroff et al. (2018) expressly identified low educational attainment, poverty, and racial disparities as issues that are undermining screening programs. In particular, according to DeGroff et al. (2018), communities across the U.S. cannot appreciate the value of screening without adequate education.

Furthermore, these scholars contend that poverty limits access to screening programs and racial disparities. This means that minorities encounter the harshest difficulties when they attempt to undergo screening. Even individuals with health insurance can run into problems resulting in their avoidance of the test. Bone et al. (2020) agreed and expressed that individuals with insurance paying a high detectable cost may go without doing their screening tests. This they attribute to the delay in insurer payouts resulting in the patient having to pay the total price of their test until their deductible is met. This could result in complete avoidance of the test by patients. These challenges demonstrate that the U.S. needs to implement systemic reforms to eliminate such issues as poverty and racism that have made it difficult for healthcare providers to deliver screening interventions to all communities. The current COVID-19 pandemic is another issue that has been implicated in the low levels of CRC screening.

Cancino et al. (2020) found that this pandemic has forced the U.S. to divert its resources and attention from such healthcare challenges as cancer toward the coronavirus. As a result, today, patients encounter obstacles when trying to receive screening for cancers like CRC. It is highly likely that due to COVID-19, thousands of CRC patients will die, and new cases that could have been prevented or detected, and treated early through screening, will progress and cause serious complications (Patel et al., 2021). While the current project does not particularly address how to resolve the challenges that adversely affect screening, it will demonstrate that through such strategies as evidenced-based personalized interventions and inclusive solutions, it is possible to improve screening rates among diverse patient populations.

Benefits of Screening

The benefits of CRC screening cannot be overstated. One of the advantages of this procedure is that it helps to reduce disease incidence. According to Khalili et al. (2020), in addition to being highly cost-effective, CRC screening facilitates the detection of CRC cases. Among communities with robust screening protocols, CRC rates are lower because these populations receive insights into the strategies and measures they can adopt to reduce their risk of CRC further. Levin et al. (2018) also found that screening pushes down the rates of CRC incidence. Unlike Khalili et al. (2020), who undertook a systematic review, Levin et al. (2018) performed a large community-based study to establish how screening would impact CRC incidence. They confirmed that, the screening program had resulted in significant improvements in screening participation and a drop in CRC incidence within a short period. This finding gave the PI the confidence that the project would demonstrate that a redesign of the screening process using the SATIS-PHI/CRC would be an effective toolkit for increasing screening rates once implemented.

In addition to reducing CRC incidence, screening has also been shown to enhance patient survival. Bone et al. (2020) are scholars who have linked screening to improved CRC survival. After holding a round table evaluation, Bone et al. (2020) found that their quality of life had been boosted and their lifespan extended, thanks to screening. Brenner et al. (2016) obtained a similar result after investigating CRC progression among patients who had received screening. According to Brenner et al. (2016), screening created a favorable prognosis for these patients. This finding is essential as it informed the hypothesis that guided the project. It is hoped that the project will show that evidence-based personalized screening dramatically lowers the risk of death.

Another benefit of screening is that it is a cost-effective solution. According to Khalili et al. (2020), the implementation of screening programs is not overly costly. Bone et al. (2020) and Subramanian et al. (2017) also found that among the qualities that make screening appealing is its low cost. More importantly, screening helps to reduce the cost of care and the huge healthcare burden that patients would otherwise incur if they were to be diagnosed with late-stage CRC. Additionally, screening bolsters the economy by preventing the productivity losses caused by ill health and death due to CRC. AHRQ’s System Approach to Tracking and Increasing Screening for Public Health Improvement of Colorectal Cancer toolkit was created to inform and educate new users and increase CRC screening programs and techniques. The toolkit is intended to assist primary care practices in providing guideline-based preventive health care to age-appropriate patients, who have a moderate risk for CRC, and who are not updated with their screening (AHRQ, 2018b).

The toolkit provides education for patients and providers about CRC screening and assists practices in encouraging, facilitating, and providing screening (AHRQ, 2018b). The AHRQ’s System Approach to Tracking and Increasing Screening for Public Health Improvement of Colorectal Cancer toolkit includes stool test, colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy, or barium enema x-ray. AHRQ maintained that the toolkit was developed consistent with research findings of effective CRC screening programs and techniques. Therefore, this toolkit includes tools, process guidelines, tips (based on lessons learned), and evidence of the intervention’s effectiveness (AHRQ, 2018b). Persons who undergo CRC screening using multiple modalities were counted only once (AHRQ, 2018b). This included only patients accessible in the primary care clinic’s electronic medical record systems, where patients’ electronic health records can be reviewed.