Introduction

- Occupational stress and interactions within a workplace environment are inseparable (Griffiths, Baxter, & Townley-Jones, 2013).

- Work-related stress results from issues such as:

- Excessive competition;

- A strenuous and conflict-filled team atmosphere;

- Ineffective communication practices (Griffiths et al., 2013);

- Dense working conditions and pressure from senior management.

- Occupational stress affects employees’ productivity (Leon & Halbesleben, 2013).

- Occupational stress and job satisfaction are strongly correlated (Aftab & Javeed, 2012; Cevenini, Fratini, & Gambassi, 2012).

- Undesirable consequences of work-related stress include:

- High turnover rates, mental health concerns, and absenteeism;

- Excess expenditures incurred through:

- Changing the work environment to meet workers’ expectations;

- Training new employees to fill the vacancies created.

- This research paper aims at:

- Discovering what techniques production and project managers of a ship-repair company in the maritime industry use to minimize occupational stress, absenteeism, turnover rates, and poor performance among employees in a company located in New Jersey

Work-related stress entails a higher risk of emotional burnout, lower performance, and depression. It arises because of excessive competition, a strenuous and conflict-fill workplace environment, and ineffective communication among others. Employees who become dissatisfied with their work environment often seek opportunities to switch jobs, thus leading to increased rates of turnover and reduced organizational productivity (Campbell, 2015; The European Agency for Safety and Health at Work, 2014; Hakanen & Schaufeli, 2012). Aftab and Javeed (2012) stated that occupational stress is particularly significant in the ship-repair industry. This line of business is associated with higher risks and greater intensity compared to other sectors of the economy. This challenge is aggravated by the industry’s low levels of managerial effectiveness.

Occupational stress is one of the key issues that managers struggle to handle efficiently (Griffiths et al., 2013). At its core, work-related stress is associated with workload intensity, workplace environment, co-worker relations, and communication strategies (Trivellas, Reklitis, & Platis, 2013). Failure on the part of management to organize employee workflow and a lack of knowledge regarding how to minimize the risks and consequences of work-related stress are the most common causes of the problem (Griffiths et al., 2013). When employees face workplace conflicts and must cope with heavy workloads, low wages, and excessive overtime hours, these factors may trigger exhaustion and dissatisfaction (Chen, Huang, Hou, Sun, Chou, Chu, & Yang, 2014). Work-related stress leads to high turnover levels, more operational expenses when organizations train new workers or transform their existing work environment to meet employees’ anticipations.

Problem Statement

- Enhancing employees’ emotional well-being prevents or minimizes the effects of occupational stress (Vainio, 2015).

- Work-related stress hinders employee performance (Britt & Jex, 2013).

- Conversely, it is the primary cause of:

- Serious health concerns and high turnover rates;

- Employee absenteeism (American Psychological Association, 2015; O’Keefe, Brown, & Christian, 2014 ).

- Additionally, occupational stress causes:

- Decreased productivity levels in 20% of employees;

- A desire to quit in 65% of employees (O’Keefe et al., 2014).

- Moreover, occupational stress costs around $150 billion in healthcare expenses annually.

- Effects of stress vary from emotional and physiological conditions such as:

- Depression and cardiovascular diseases;

- Emotional disorders.

- The effects also include serious organizational issues, including:

- Lower job performance and employee-based conflicts;

- Workplace injuries related to mental disturbances and lack of concentration (Halbesleben, 2013;).

- Employees in the ship-repair industry work in a highly demanding environment (Cardoso et al., 2014; O’Keefe et al., 2014).

- Factors that contribute to occupational stress in this industry include:

- Working 7 days a week, absenteeism, and turnover rates;

- Insufficient work–life balance (Cardoso et al., 2014).

- Work-related pressure that ship-repair industry workers face is rather high (Al-Raqadi et al., 2015).

- This pressure is present because of:

- The industry itself;

- Jobs involved in the sector (Cardoso et al., 2014).

- Occupational stress in the ship-repair industry remains elevated (O’Keefe et al., 2014) because of:

- Absenteeism;

- Turnover rates;

- Poor employee performance.

- The sector experiences a knowledge gap regarding effective techniques to reduce work-related stress.

- I conducted a study at a ship-repair company.

- The aim was to gain an in-depth understanding of techniques that production and project managers use to address the aforementioned issues.

Managers often lack the knowledge required to reduce occupational stress caused by long working hours and frequent accidents. They are also poorly equipped with mechanisms for overcoming stress-related organizational difficulties (Al-Raqadi, Abdul Rahim, Masrom, & Al-Riyami, 2015; Cardoso, Padovani, & Tucci, 2014; Cezar-Vaz, de Almeida, Bonow, Rocha, Borges, & Piexak, 2014). As a result, work-related stress becomes an issue that interferes with employees’ performance because it is linked to adverse health concerns, absenteeism, and high levels of job quitting.

Work-related stress is a costly issue that has been linked to high healthcare expenditures. It is associated with depression and cardiovascular diseases, including emotional disorders. Employees suffering from these conditions perform poorly, engage in frequent conflicts, are prone to workplace injuries because of their mental issues.

In the ship-repair industry, heavy workloads, hazardous working environments, and strenuous workplace atmospheres lead to the recorded high levels of work-related stress. Although risks of occupational stress are similar across different sectors of the economy, they are significantly higher in this industry because of the lack of knowledge regarding work-related stress and its effects.

The gap in the ship-repair industry not only results from a failure to recognize the importance of preventative measures but also the ineffectiveness of the techniques used (Sherridan & Ashcroft, 2015). Enhancing the emotional well-being of employees is the key to preventing occupational stress and minimizing its negative effects (Vainio, 2015). Although Britt and Jex (2013) claimed that work-related stress boosts employee performance, it is conversely the primary cause of serious health concerns, high turnover rates, and employee absenteeism (American Psychological Association, 2015; O’Keefe et al., 2014). Conducting a study in this sector aimed at establishing an in-depth understanding of strategies deployed by managers to curb such adverse health issues linked to occupational stress.

Purpose Statement

- This qualitative exploratory case study sought to discover techniques that production and project managers of a ship-repair company in the maritime industry use to minimize:

- Occupational stress;

- Absenteeism;

- Turnover rates;

- Poor employee performance.

- Information was obtained through interviews and company policy and attendance records.

- Eight project and production managers were interviewed.

- Interviews entailed open-ended questions.

- The data could help to reveal:

- Peculiarities of work-related stress in the ship-repair industry;

- The effect of stress on employee turnover, performance, and absenteeism.

- Questions were used to elicit the interviewee’s perceptions of occupational stress.

- The company policy documents and a reflective diary used during the interviews were helpful in:

- Addressing a range of societal and organizational issues related to professional stress;

- Improving techniques used to reduce stress in the work environment.

The current study sought to find out various mechanisms that have been established by a ship-repair company’s production and project managers to eliminate or minimize the effects of work-related stress such as absenteeism, turnover, and poor employee performance. Interviews and the use of the company’s policy and attendance records helped to gather the required information.

Interviews conducted contained open-ended question that helped to gather information concerning peculiarities of occupational stress and its contribution to employees’ turnover, poor performance, and absenteeism.

Theoretical/Conceptual Framework

- This study is founded on the Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) model.

- The model forecasts the potential influence of increased job demands on the level of occupational stress (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014).

- High job demands and resources are two aspects of the JD-R model (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014; Xanthopoulou , Bakker, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, 2007).

- Job resources entail measures that promote employees’ health and well-being.

- The model centers on several different features of a work environment, including:

- Organizational characteristics;

- Social characteristics;

- Physical characteristics;

- The link between the above characteristics and employees’ physical and emotional dedication to job functions.

- Job resources have a positive influence on both employees and employers

- They:

- Increase levels of employee dedication;

- Foster personal growth and a desire for self-development;

- Increase workplace enthusiasm (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007).

- Work engagement and emotional burnout significantly affect employee well-being.

- Thus, they are the primary causes of work-related stress (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014).

- High job demands are inseparable from two aspects of the working environment:

- Employees’ aspirations;

- Employees’ levels of dedication (Xanthopoulou et al., 2007).

According to the Job Demands-Resources model, work engagement and emotional burnout are two factors with the most significant effect on employees’ well-being and hence the primary causes of work-related stress (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). The first aspect, high job demand, is practically synonymous with the cause of professional stress. On the other hand, resources refer to the totality of steps and measures taken to reduce occupational stress and improve employees’ well-being (Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). However, to guarantee a positive correlation between job demands, resources, and employee performance, it is imperative for companies to find the right balance between available resources and employee satisfaction. If this balance is not achieved, the results of applying the JD-R model and changing the work environment may differ from the existing theory or even be negative (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). The model’s significance for achieving the purposes of this study cannot be underestimated because it was used to ascertain whether higher job demands were indeed sources of work-related stress among employees in the ship-repair industry and to gain a better understanding of causes of occupational stress, an invaluable piece of information for any organizational manager.

Work engagement and emotional burnout are closely related to job demands, which are, in turn, directly connected to occupational stress and employee performance (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Employees’ personal aspirations such as their dedication and desire to do a good job form the foundation of positive employee performance and high productivity. However, such aspirations can also lead to burnout. Indeed, dedication to work inevitably leads to higher demands and more pressure from senior management, thus increasing the risks of occupational stress and creating a more strained team atmosphere-which, in turn, may result in various health concerns and an increasingly negative perception of the workplace and of the employee’s own position in the company (Xanthopoulou et al., 2007).

Nature of the Study

- This research was a qualitative exploratory case study.

- It was a promising choice for this research.

- According to O’Sullivan, Rassel, an Berner (2008), qualitative research is an efficient tool when:

- Evaluating individual experiences;

- Evaluating societal background;

- Obtaining an in-depth understanding of the issue under investigation.

- The research is about managers’ personal perceptions of occupational stress and related past experiences.

- The elaboration of this study’s research question was to focus on:

- The perceived knowledge and individual experiences;

- Insights of the interviewee.

- The research adopted a case study design.

- Case studies naturally complement qualitative research.

- They provide a thorough understanding of the issue at hand.

- This design was chosen because of:

- The study’s focus on managers and employees working in one environment;

- The desire to investigate how this environment influences them.

- This qualitative exploratory case study was based on several constructs.

- The design focused on expressive, logical, and knowledge-based constructs.

- Data was obtained from sources such as interviews and company documents.

- The interviews consisted of open-ended questions.

- The present study consisted of a small sample.

- The sample included eight production and project managers employed at a ship-repair corporation in New Jersey.

- A coding process for analyzing all the data and grouping the codes into categories was used (Theron, 2015).

- Through the coding process, the researcher expected to:

- Find unbiased results to this study;

- Obtain a better understanding of interviewees’ perceptions of occupational stress.

According to Frels and Onwuegbuzie (2013) and Dworkin (2012), qualitative research is useful for drawing accurate conclusions based on small sample sizes. Unlike quantitative research, a qualitative study does not require the identification of reason-and-consequence relationships or the presence of a large sample; neither does it call for the incorporation of quantitative aspects into qualitative studies, as witnessed in the case of mixed research designs (Caruth, 2013; Lund, 2012). Quantitative methods focus on data analysis from a large number of cases from randomly selected respondents (Lund, 2012). The nature of this study fits the current subject about managers’ perceptions of occupational stress and related past experiences.

A case study design is a natural choice when the focus of the research is on investigating current subjects that are affected by transformations in their environments (Yin, 2013). This design fits qualitative studies such as the current one that focuses on managers and employees working in one environment. Roller and Lavrakas (2015) stated that constructs are key topics relevant throughout interviews because of their importance and involvement in the process of finding accurate answers to research questions. According to Roller and Lavrakas, expressive constructs refer to the emotions and experiences of a respondent while logical constructs and those connected to knowledge are associated with the participant’s ability to assess his or her current environment in an unbiased manner. Case studies are most effectual when exterior factors, not the researcher, trigger the actions and responses of research participants (Yin, 2013).

According to King and Horrocks (2010), interviews and company documents are effective data collection tools for scrutinizing the diversity of perceptions of the subject under investigation and for gaining detailed insight into the research topic. As compared to close-ended questions, open-ended questions are more useful for collecting facts and perceptions connected to the interviewees’ personal experiences (Seidman, 2013). Open-ended questions motivated interviewees to share their personal feelings and experiences regarding occupational stress.

Particular answers from the interviews could give the researcher an in-depth understanding of the subject (Grbich, 2013). According to Seidman (2013), open-ended questions and interviews are the best options for gathering the data and evidence necessary to understand the worldviews of participants. Small samples allowed the researcher to obtain a thorough understanding of the research topic (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2014). To maintain a small sample, interviews were limited to people who were at that time employed by a single corporation in the ship-repair industry.

Research Questions

To achieve the research objectives, gain a comprehensive understanding of the research problem, and fill the existing knowledge gap regarding occupational stress in the ship-repair industry, it was imperative to focus on the following research question:

- Q1.What techniques do production managers and project managers at a ship-repair company use to reduce work-related stress?

The research question is founded on the understanding that production managers need to be aware of their industries and work environments, which they can tailor to minimize stress on their workers. They need to consider their employees’ needs in devising strategies for minimizing stress. Hence, the research question examines various strategies that production managers deploy to maximize workers’ efficiency and performance while mitigating the effects of stress.

Significance of the Study

- It fills the existing gap in the knowledge of some effective techniques for reducing occupational stress in the ship-repair industry.

- The study is significant for leaders and practitioners in the field.

- It enhances their better understanding of the effectiveness of various stress-reducing techniques.

- The study is helpful for PhD students.

- It contributes significantly to their improvement of numerous organizational frameworks for:

- Minimizing the risks of professional stress;

- Mitigating its negative consequences on employees’ physical and psychological well-being.

The study seals the knowledge gap regarding various effective strategies for mitigating work-related stress in the ship-repair sector. Managers employ a variety of techniques to diminish the risks of work-related stress and eliminate its negative influences, with emotion-focused and problem-focused strategies being the two central types of tools for addressing the issue (Meško, Erenda, Videmšek, Karpljuk, Štihec, & Roblek, 2013). In the maritime industry, demanding working conditions and a lack of managerial knowledge necessary to reduce stress aggravates the challenge of professional stress. Leaders and practitioners will get information on the strategies to use when minimizing occupational stress, absenteeism, turnover rates, and poor employee performance. For PhD students, the study provides a launching point for further investigation of related issues, including occupational stress reduction frameworks. Hence, frameworks developed by PhD learners in the course of their research may be helpful in addressing this issue.

Definition of Terms

- Job performance.

- Job satisfaction.

- Motivation.

- Productivity.

- Stress.

Job performance refers to the different behaviors in which employees are engaged while carrying out their job duties and fulfilling their work functions (Gupta, Kumar, & Singh, 2014). Job satisfaction refers to an individual’s positive emotional perception of his or her work and contentment with the job environment and conditions connected to the professional experience (Gupta et al., 2014). Motivation refers to the inner force that drives individuals to accomplish job tasks and achieve any predetermined goal, either personal or organizational (Naqvi, Khan, Kant, & Khan, 2013). Productivity refers to the ratio of output to input and the real productivity per unit of labor (Naqvi et al., 2013). Stress refers to the interdependence between an individual and demands from managers or job duties within an environment (Naqvi et al., 2013).

Review of the Literature

Literature Search Strategy

- A thorough online search of the existing literature was the foundation for writing this chapter.

- Articles accessed from the library were selected from:

- Google’s search engine;

- The Google Scholar database.

- For purposes of this research, no limitations were put in place regarding:

- The country of origin of the materials selected;

- The database for choosing articles.

- The goal was to:

- Guarantee the inclusion of all relevant literature;

- To avoid the possibility of missing some valuable information.

- Some criteria were established for choosing the source of information.

- The inclusion depended on the nature of the sources.

- The literature review included scholarly articles published in peer-reviewed journals.

- The goal was ensure research credibility.

- Preference was given to papers published within the last three years (2014-2017).

- However, some older sources were included to estimate:

- The dynamism of changes in the perceptions of occupational stress;

- The primary stressors in the workplace.

Apart from the effect that occupational stress has on employees, it also affects organizations by harming brand image, fostering negative changes in the workplace atmosphere, and wasting valuable human resources, especially when employees switch jobs hoping to get a more comfortable place to work and higher chances for career development. To secure studies whose content could capture this information, a variety of keywords were targeted in the searches, including workplace stress, occupational stress, causes of work stress, workplace stress outcomes, job dissatisfaction causes, turnover causes, depression, and stress coping mechanisms. Google’s search engine and Google Scholar served as sources of articles to be examined. Such articles where not limited to a particular country of origin to ensure that all appropriate materials were included in the literature.

During the search process, primary emphasis was placed on the causes of occupational stress in the ship repair industry. However, sources were not limited to those specifically covering the maritime industry because, in most cases, the causes of workplace stress and turnover intentions are similar across different career fields and industries. Occupational stress is one of the most serious challenges for leaders and managers (Aftab & Javeed, 2014). Because working environments have grown highly competitive and increasingly intense, employees find themselves caught in taxing atmospheres and experiencing constant mood swings because of harsh working conditions and the necessity to foster personal development to remain employed (Dwamena, 2012). Although many researches have been conducted regarding this subject since the 1980s, preference was given to the latest materials published from 2014 onwards, although few older sources were included. Scholarly materials from peer-reviewed journals were selected.

How the Review was Organized

The review is organized as follows:

- A coverage of a model of occupational stress and its effects.

- An overview of what occupational stress entails.

- The effects of occupational stress on employees with an emphasis on employee productivity in stressful environments.

- The effects of occupational stress on organizations with an emphasis on how workplace stress affects the ship repair industry.

- Different strategies that may be employed to minimize and mitigate occupational stress.

The literature review includes several subsections that provide further details on topics related to occupational stress, identifying the nature of the concept in the first place and then investigating job satisfaction, employee absenteeism, employee productivity, and strategies used for minimizing the risks of occupational stress in the ship-repair industry. The motivation behind the division is a desire to provide insight into matters related to professional stress and clearly point to the existence of the knowledge gap in the existing literature, underpinning the significance of the present study.

Key Theories

- The theoretical framework presented is focused on employee engagement theory.

- Influence from transformational leadership theory results in the study’s testability being afforded by the job demand-resources (JD-R) model.

- The two theories enable the use of the JD-R model.

- Managers utilize the model to ascertain the demands placed on workers.

- It helps in noting the resources put in place for workers to facilitate goal achievement.

- Employee engagement is connected to occupational stress and employees’ psychological well-being (Robertson & Cooper, 2009; Simon & Amarakoon, 2015).

- Occupational stress is a challenging problem in modern workplace organizations.

- It has adverse effects on employees’ welfare and an organization’s future.

- Work-related stress causes serious health concerns such as:

- Cardiovascular diseases;

- Depression.

- The two affect an organization’s performance and success (Cevenini et al., 2012).

- Preventative and educational measures are critical.

- The occupational stress indicator (OSI) is critical when discussing the conceptual framework for work-related pressure.

- This approach to occupational stress helps in:

- Viewing the phenomenon from four different angles in every unique situation;

- Determining its magnitude and nature that can help to prevent occupational stress or minimize it;

- Occupational stress can occur in a variety of different career fields and industries.

- Regardless of field or industry, avoiding workplace stress altogether is impossible (Griffiths et al., 2011).

Employee engagement theory has its basis on the necessity of balance, as provided by the organization and management, of practices that help to mitigate and minimize stress without completely eliminating challenges and the motivation necessary for workers to do a good job. The transformational leadership theory focuses on the need for managers to want to ensure that the workplace environment is as free of debilitating and unnecessary stress as possible while promoting worker exceptionalism. Employees affected by the negative outcomes of occupational stress such as emotional burnout, depersonalization, exhaustion, low job satisfaction, and absenteeism are likely to be disengaged from their professional duties. At the same time, Simon and Amarakoon (2015) argued that a completely stress-free workplace environment may also result in workers’ disengagement. According to this theory, employee engagement is based on a balance of anti-stress strategies put into practice by workplace leaders and managers and a set of motivational tasks that create a healthy level of office intensity, thus making the working process active, involving, and stimulating to achieve a desired level of performance. The theory that served as the theoretical foundation of this study was transformational leadership theory. An organization’s leader is seen as able to impact employees’ well-being by means of fostering positive organizational change and developing trusting relations with workers (Liu, Siu, & Shi, 2010; Lyons & Schneider, 2009). The JD-R model provides a basis for a deeper understanding of occupational stress and its causes, as well as conditions that lead to its increase and decrease.

Cevenini et al. (2012) maintained that the phenomenon of occupational stress is inseparable from the concept of occupational health, meaning that external factors specific to a particular working environment affect both the physical and emotional well-being of employees. Just like health promotion, the issue of occupational stress should be addressed by monitoring and satisfying the needs of staff, eliminating potential risks, and recognizing the severity of consequences. In addition to the associated health concerns, there exists a broad range of minor and significant physical signs and symptoms of occupational stress, some of which are compromised professional judgment, depressive or negative outlook on life and work, mood swings and irritability, aches and pains in different areas of the body, a feeling of frustration, dizziness, nausea, constipation or diarrhea, elevated heart rate, starving oneself or binge eating, loss of sleep, chronic fatigue, procrastination, or a neglectful attitude toward one’s professional duties and responsibilities (Ajaganandam & Rajan, 2013). According to Cevenini et al. (2012), an effective approach includes both preventative and educational measures that point to the significance of health and job productivity promotion, including the need for teaching managers to identify signs of occupational stress and strategies to cope with it.

The OSI was first outlined at the end of the 1980s within the Michigan occupational stress model. It was said to include four core aspects such as sources and causes of occupational stress, persons who are affected by these negative influences, effects that occupational stress produces, and coping strategies used for the purpose of overcoming it (Annamalai & Nandagopal, 2014). Indeed, the increased opportunity for virtual work decreases the risk of absenteeism and presenteeism. It also eradicates the challenge of heavy workloads and interpersonal conflicts because there is no physical working environment. However, occupational stress is not limited to the ship-repair industry. Hence, since it cuts across all sectors, eliminating it may be impossible.

Workplace Stress in the Ship Repair Industry

- The primary focus of employees in the ship-repair industry is always on safety issues.

- Safety is a central determinant of employee productivity (Al-Raqadi et al., 2015).

- In the shipbuilding and ship-repair industries, levels of occupational stress are high.

- They are high compared to those of other sectors.

- Addressing the problems calls for the implementation of:

- Gender-based strategies;

- Education-based strategies;

- Job characteristics that help to overcome the challenges or workplace stress;

- Preventive strategies.

The ship-repair industry is characterized by the existence of a variety of specificities. For example, the primary focus of employees is always on safety. Bakotić and Babić (2013) highlighted the significance of safe and comfortable working conditions for both the emotional and physical well-being of employees. Constantly working under the realization of the high risk of work-related accidents is another critical stressor affecting dock workers and those employed by ship-repair companies (Cezar-Vaz et al., 2014). To effectively address stress at work, it is also imperative to keep in mind the roots of this complex phenomenon and incorporate the primary aspects of the determinants into stress coping techniques. Mosadeghrad (2014) noted the existence of a correlation between the level of education (perceived knowledge) and the risk of occupational stress, as characterized by the following trend: lower academic performance entails lower chances for high-paid work, thus, leading to higher risks of workplace stress. Job demands, job control, and social support are common causes of occupational stress (Adriaenssens, De Gucht, & Maes, 2015). However, these aspects can become the foundation of another strategy for coping with the challenges of workplace stress. Another comprehensive opinion on addressing occupational stress is that of Maran, Varetto, Zedda, & Ieraci, 2015), demonstrating the significance of preventative measures as the foundation for any effective stress coping strategy.

Research Methodology and Design

- Qualitative research method was the most suitable.

- It does not require testing hypotheses or generalizing (Caruth, 2013; Frels & Onwuegbuzie, 2013).

- The selected research design was a case study.

- It was useful for:

- Drawing accurate conclusions;

- Making recommendations based on personal experiences;

- Understanding the research subject;

- Analyzing situations and behaviors affected by the external environment instead of the researcher (Yin, 2013).

Finding accurate and relevant answers to this study’s question required the selection of an appropriate research method. Because the focus of the study was analyzing personal experiences, behaviors, and social contexts, qualitative research method was the most appropriate (O’Sullivan et al., 2008). Moreover, the qualitative research method is the only one that paves the way for an in-depth understanding of a chosen phenomenon while focusing on different aspects of a research subject (Lund, 2012). It is also the only method that justifies the use of small sample sizes because they are valuable for obtaining a deeper understanding of the matter of interest (Dworkin, 2012). Crowe, Creswell, Robertson, Huby, Avery, and Sheikh (2011) specified that the case study design is the best choice for research that entails an analysis of respondents’ natural environment and for issues that dynamically change over time under the influence of external factors such as alterations in techniques for reducing occupational stress or changes in working conditions or schedules.

Population and Sample

- The target population was project and production managers of a ship-repair company in New Jersey.

- The rationale for choosing the area was the number of ship-repair companies operating there (Maritime Association of the Port of New York/New Jersey, 2016).

- The population was appropriate because respondents had enough professional competence and experience.

- Sample selection was based on purposeful and stratified sampling techniques.

- Each potential interviewee’s professional background was reviewed to ascertain their knowledge and experience levels.

- In this manner, the researcher purposely chose appropriate participants.

- Several criteria for selecting respondents were appropriate:

- Occupying a particular position within the company;

- Having a lengthy tenure (at least 5 years);

- Working within one department.

- Sampling guidelines were followed by including the last stratum to mitigate risks of respondent heterogeneity.

- The sample consisted of eight project and production managers from the chosen company.

- Data saturation was reached via the use of a small sample of eight people.

- It helped to gather adequate information for coding (Fusch & Ness, 2015).

The primary location for data collection was New Jersey. The given setting increased the opportunity to choose people with enough knowledge and expertise to achieve the research objectives, collect the appropriate data, and reach accurate conclusions while at the same time reducing the risks of excessive heterogeneity (Roller & Lavrakas, 2015). The basis of purposeful sampling is the assumption that only those with an adequate background and level of knowledge about the issue under consideration should become respondents because they are the only people who can provide the required information and the level of details (Miles et al., 2014). Stratified sampling is a useful supplement to purposeful sampling. This sample selection method allowed the researcher to gather more accurate data.

A small sample was the best way to conduct individual interviews necessary to collect enough information to achieve the research objectives (Crouch & McKenzie, 2006; Hesse-Biber, 2016). Moreover, it was the best approach to drawing comprehensive conclusions because it considers multiple perceptions and worldviews.

Material/Instrumentation

- Interviews were the primary tool for data collection.

- A reflective diary was used to collect notes during interviews.

- Individual stress level tests and experiments for assessing one’s stress-management skills are available.

- However, no tests can assess stress-coping techniques for the present study.

- NVivo 10 software was used for data processing and analysis.

- The researcher was given permission for have full read/write access to the suitable elements of the registry.

Interviews were carried out with each of the participants individually and recorded by means of a voice recorder. As a tool, they require the use of different materials such as an interview guide, which not only contains questions but also directs the collection of data (Castillo-Montoya, 2016). NVivo program helped to avoid errors common to manual processing. The researcher was granted permission to use the program. The tool increases the possibility of drawing accurate conclusions. It also reduces the time required for data processing and recommendations (Shaw & Holland, 2014). Although there exist individual stress level tests and mechanisms for assessing one’s stress-management skills, no instruments have been established to assess stress-coping techniques that form the focus of the present study. The techniques are unique to each individual and vary depending on the employees’ preferences, habits, and personalities among other factors.

Study Procedures

- Interview guides were used to ensure that the same questions are asked.

- They allowed respondents to discuss the same topics (Roller & Lavrakas, 2015).

- They included a list of interview questions covering all topics related to occupational stress.

- A pilot interview was done using a test sample.

- Data validity was guaranteed using triangulation of analyses.

- Coding was the instrument used to detect patterns and themes in participants’ responses.

Even though interview questions were open-ended, thus making them adaptable and easy to change in the course of an interview, it was imperative to use the interview guide to ensure that the same questions were asked and that the similar topics were discussed with all respondents (Roller & Lavrakas, 2015). A pilot interview ensured that questions developed were appropriate for the collection of meaningful data. After conducting the process, finalizing reflective diary, collecting the old and new company policy, and gathering additional company documents, it was necessary to ensure data validity. To avoid any possibility of bias, the use of coding provided typing and analysis for each of the interviews. It helped to group patterns and themes together for future analysis.

Data Collection and Analysis

- Several basic strategies were taken to define major coding categories (Saldana, 2015).

- Specific short titles were used to categorize the information in interviewees’ answers.

- The researcher organized, coded, grouped , and analyzed the data using NVivo 10 software.

- Data processing included the transcription of collected statistics.

- Respondents were requested to check the accuracy of transcripts (Shaw & Holland, 2014).

- Triangulation efforts enhanced the reliability and validity of the collected data.

Key aspects of the coding process are that categories should be broad enough to cover the entire body of interviews with all of its topics and themes (Vaismoradi, Jones, Turunen, & Snelgrove, 2016). The classification of responses by similarities in perceptions and experiences helped the researcher to analyze the data and draw accurate conclusions (Shaw & Holland, 2014). The main selection criterion was that each participant had successfully used a technique to reduce work-related stress at a ship-repair company. The purpose of data processing entails making sense of the obtained facts and using them to find answers to the research question (Roller & Lavrakas, 2015). Data processing involves the fractionalizing and conceptualization of answers, a step that is completed by identifying the most frequently occurring concepts and topics in the interviews (Miles et al., 2014).

Assumptions, Limitations, and Delimitations

- It was assumed that:

- Respondents represented the perceptions of employees and managers in the ship-repair industry;

- Respondents were open and honest during interviews;

- Respondents possessed the appropriate knowledge and information;

- Enough data and facts were collected during interviews.

- The small sample size of 8 was a limitation.

- It threatened:

- The accuracy of conclusions and recommendations;

- The generalizability of research findings.

- Unwillingness of respondents to participate in the research was another limitation.

- The need for manual data input was an additional limitation.

- The central concern entailed the sample size and respondents’ competence.

- Selecting only people currently employed and working within one workplace environment was the central delimitation.

- It helped to draw conclusions for the given environment.

- The small sample size was also a delimitation.

Assumptions in qualitative research are ideas that a researcher believes to be true and basic, which make up the foundation of the study. The sample was assumed to reflect the whole population of interest (Yin, 2013). According to Miles et al. (2014) and Palinkas, Horwitz, Green, Wisdom, Duan, Hoagwood (2015), openness and honesty guarantee that all obtained facts are relevant, accurate, and generalizable, reflecting the current matters of concern in the maritime industry. Enough data eliminated the need for carrying out more interviews or gathering more information. According to Flick (2014), limitations are structural features of a research study that impose risks of drawing inadequate conclusions or failing to reach research objectives. A significantly small sample of 8 elements was a limitation to the current study because it compromised the generalizability of the findings obtained.

Unwillingness to participate in the research may be witnessed due to some personal or work-related obligations on the day of conducting interviews (Emmel, 2013). Addressing the study’s limitations extended the time required to collect and process data, thus increasing its cost. Reducing the scope of generalizations to the chosen ship-repair company instead of the maritime industry as a whole was the central guarantee of appropriate findings of the research and recommendations. Delimitation is the process of eliminating repetitive, inaccurate, or overlapping data. According to Dworkin (2012) and Crouch and McKenzie (2006), small samples are the most appropriate option for obtaining an in-depth understanding of the research subject.

Ethical Assurances

- An IRB approval was received on 9/20/2017.

- The study only had minimal risks to participants.

- Consent of the senior management of the company under investigation was acquired.

- Employee confidentiality and company anonymity were guaranteed.

- Informed consent of interviewees was obtained.

- Interview questions were unbiased.

Researchers need to collect, process, and store data without breaching the privacy and confidentiality of the respondents or exposing them to ethical issues in the workplace. At the same time, ethical assurances have a direct influence on the dissemination of research findings and the recognition of their significance by higher levels of the academy (Roller & Lavrakas, 2015). According to Hennick, Hutter, and Balley (2011), guaranteeing the right to self-determination, together with confidentiality and anonymity, is the only option for ensuring the safety of participants in studies similar to the present one where no physical or psychological risks exist. By conducting interviews in a gender-neutral and race-neutral manner, the researcher can avoid bias and foster the trust and openness of respondents, thereby maximizing chances of collecting relevant and accurate data (Miller, Mauthner, Birch, & Jessop, 2012).

Findings

- Work environments affect the level of employees’ stress.

- The work environment is formed by:

- vInterpersonal relations between members of the company;

- vThe nature of the workplace norms.

- Occupational stress contributes greatly to emotional exhaustion.

- Work-related stress inhibits performance and productivity.

- The lack of comfort and overabundance of work-related conflicts are antecedents of stress.

- A thematic link prevails between work-related stress and its effects.

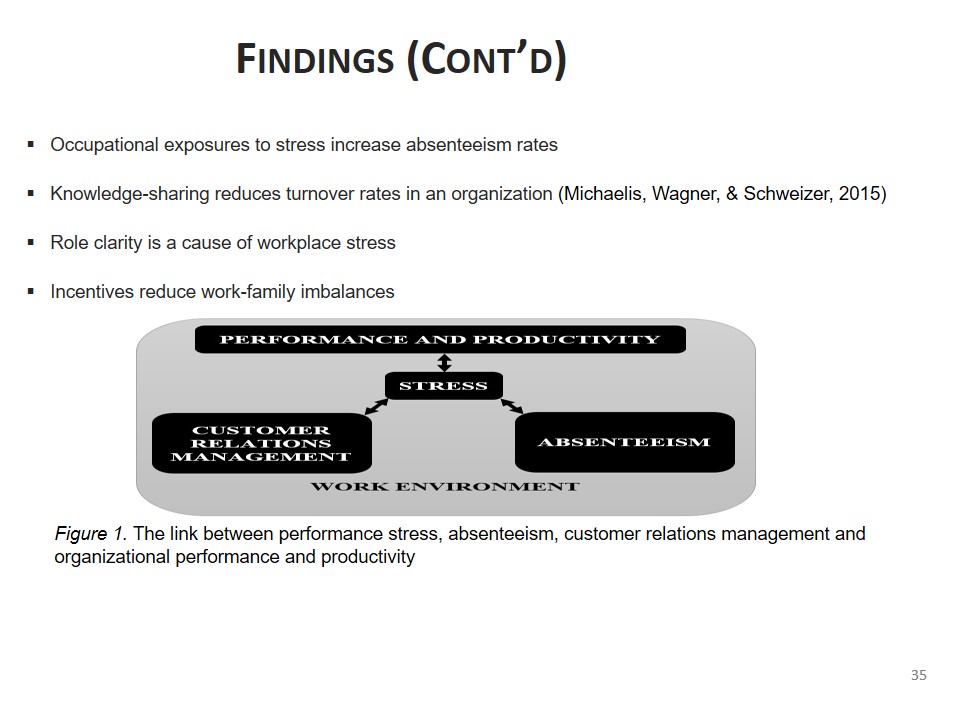

- Occupational exposures to stress increase absenteeism rates.

- Knowledge-sharing reduces turnover rates in an organization (Michaelis, Wagner, & Schweizer, 2015).

- Role clarity is a cause of workplace stress.

- Incentives reduce work-family imbalances.

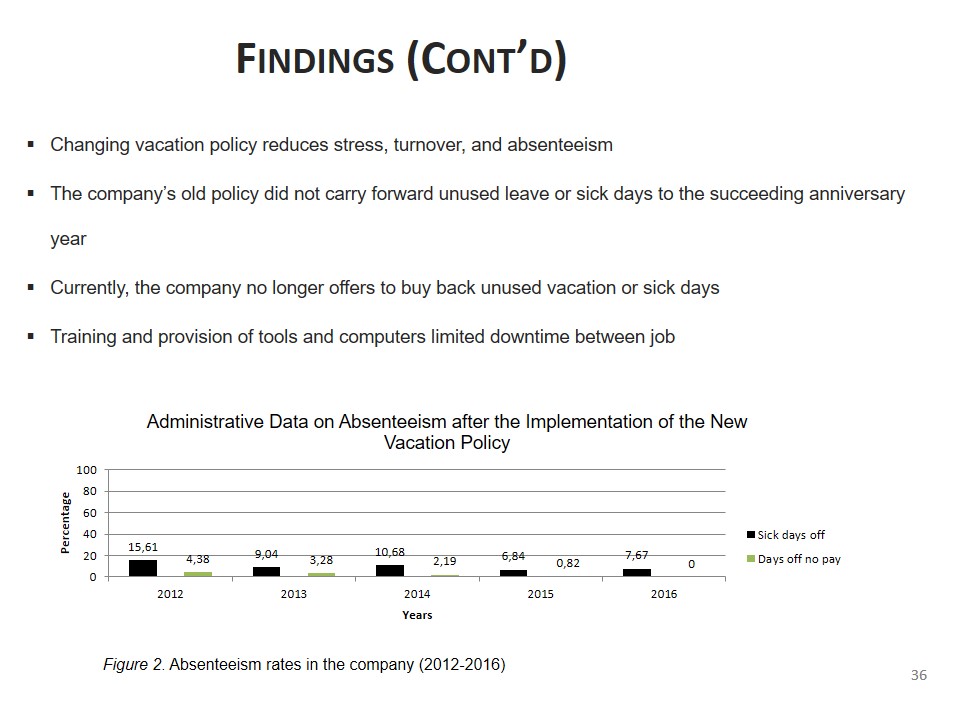

- Changing vacation policy reduces stress, turnover, and absenteeism.

- The company’s old policy did not carry forward unused leave or sick days to the succeeding anniversary year.

- Currently, the company no longer offers to buy back unused vacation or sick days.

- Training and provision of tools and computers limited downtime between job.

Emotional and social experiences of workers in the company are substantial contributors to mental strain or lack thereof in the workplace. Production and project managers of the ship-repair company argued that different work environments are characterized by various levels of stress. Emotional exhaustion has deleterious effects on employee well-being. The detrimental effects of stress span a large number of health indicators and facets of employees’ lives. Responses to this question emphasized that the work environment could contribute to increased or decreased workplace stress depending on its nature.

A study by Mullan (2014) suggested that stress mediates the relationship between insomnia and depression, which are conditions that can result in negative health outcomes for employees. It follows that workplace stress is a causal agent of health problems, which are key antecedents of involuntary absenteeism (Marzec, Scibelli, & Edington, 2014). Respondent P5 mentioned “knowledge exchange can both boost productivity,” hence reducing the level of stress experienced by the workforce. The effect of proper information flow on the elimination of stress has been well explored in the field of business research. Specifically, the sentiment adopted by the fifth participant was supported by a study suggesting that knowledge management plays a mediating role between stress and performance (Michaelis et al., 2015). Communicating responsibilities that an employee undertakes is essential for reducing uncertainty concerning their professional functions. Participants in the study conducted by Lyness and Judiesch (2014) pointed to the disruption of work-life balance as one of the causes of work-related stress.

In 2014, the ship-repair company changed regulations on employee vacations in an attempt to reduce turnover intentions. The change led to a steep decline in turnover rates from 17.62% in 2012 to 1.72% in 2014. Even though there was a marginal increase in turnover in 2015 (3.57%), the following year was marked by an extremely low percentage of employees who left the company (1.78%). The new policy was developed to diminish emotional exhaustion of workers, thereby ameliorating negative effects of stress on the workforce. Currently, employees have 5 days of mandatory earned paid leave. They need to take up the remaining paid leave days within the specified period or lose the earned benefit. The policy change has promoted more workers to attain a proper work-life balance according to the data that the company provided. Assisting employees by putting them in situations to succeed” leads to an increase in performance.

Evaluation of the Findings

- Respondents highlighted the effects of work environment on employee stress.

- In line with previous studies, a safe workplace contains fewer stressors for workers (Smit, 2014).

- The presence of stressors lowers workers’ ability to complete their functions effectively.

- Previous studies suggest that workplace stress has negative effects on employees and organizations (Bakker & Demerouti, 2014).

- The absence of good communication strategies leads to a stressful environment.

- Bidirectional communication reduces stress and conflicts among workers (Swanson, Territo, & Taylor, 2016).

Respondents stated that making a positive workplace allows employees to undertake their functions better because it reduces stress. It was proposed that an organization should seek to reduce the occurrence of traumatic events to employees as one of the approaches to eliminating stress. Strained employees are more likely to exhibit confrontational inclinations than their counterparts with better stress-coping skills (Swanson et al., 2016). The employee engagement theory is based on the organizational and managerial role of ensuring a balance between the activities of mitigating workplace stress and challenging employees to perform better through motivation (Truss, Alfes, Delbridge, Shantz, & Soane, 2013). These findings are consistent with the results obtained by other researchers who have collected evidence on organizational improvements that arise from employee development programs (Cerasoli, Nicklin, & Ford, 2014).

Implications

- Factors that informed the interpretation of results include:

- vManagers’ active development and use employee stress reduction strategies in the ship-repair industry.

- The results address the study problem that the work environment contributes to occupational stress.

- It adds to the existing literature indicating that environment-related stressors are not confined to the ship-repair industry.

- Results obtained are largely consistent with the existing research and theories.

- For instance, the suggestion about time off aligns with the findings of a study by Lyness and Judiesch (2014).

- However, clarity and feedback appeared to be more important in this study than in previous studies.

The connection between work-related stress and managerial planning has received attention in academia. For example, Truss et al. (2013) studied the effects of work-related stress on organizational performance and stated that planning could be difficult to implement if the level of uncertainty was high. This study’s findings are consistent with the underlying principles of the JD-R model, as well as with employee engagement and transformational leadership theories. All three theories stress the relaxing of professional demands at times of heightened personal stress to assist employees in achieving a positive work-life balance (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Lyness and Judiesch (2014) found that a failure to balance excessive work with personal life results in adverse outcomes at organizational and individual levels. However, the divergent finding concerning the elevated importance of clarity and feedback in this study is attributable to the complexity of the ship-repair industry.

Recommendations (practical application)

- Managers in other organizations should identify key contributors to stress and develop strategies accordingly.

- The selected ship-repair company was found to face specific issues, particularly regarding communication.

- Cardoso et al. (2014) stated that reducing employee stress is a key managerial responsibility.

- Managers should offer continuous staff training and development.

- Communication was a primary concern for the organization being studied.

- Swanson et al. (2016) addressed the correlation between external communication and employee stress.

Managers have a responsibility to understand key stressors affecting their employees and to provide training to help workers in coping with those particular stressors (Cardoso et al., 2014; Ford, 2014). Despite its specificity to the organization under study, the finding related to communication skills development aligns with previous literature indicating that negative attitudes from customers can lead to lower job satisfaction among workers, especially when such mindsets are related to employee performance dimensions that they (employees) cannot control (Lam & Mayer, 2014).

Recommendations (future research)

- Future studies should find out the extent to which findings of this research align with strategies used elsewhere.

- Such studies may overcome the limitations of a case study research.

- The use of quantitative methods like survey research in the future may equip researchers with descriptive statistics (O’Sullivan et al., 2008).

- Such quantitative studies are generalizable to other settings (Lund, 2012).

- Causes and solutions to stress identified by managers may differ from what employees specify.

- The next logical step may entail a study comparing managers ‘ expectations and employees’ needs and anticipations.

The present investigation addressed the views of managerial staff. However, one limitation is that it is not possible to draw conclusions regarding employees’ perceptions of organizational stress. Therefore, a future similar study examining employees and managers’ demands and expectation may be instrumental in identifying the most effective strategies to reduce occupational stress and in minimizing wasted resources. If managers implement strategies that are not aligned with employees’ needs, a gap may arise between the cost of stress-reduction strategies and a lack of resulting change.

Conclusion

Thank you for your attention.

“Are there any questions?.

References

Adriaenssens, J., De Gucht, V., & Maes, S. (2015). Causes and consequences of occupational stress in emergency nurses, a longitudinal study. Journal of Nursing Management, 23, 346-358.

Aftab, H., & Javeed, A. (2012). The impact of job stress on the counter-productive work behavior (CWB): A case study from the financial sector of Pakistan. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 4, 590-604.

Ajaganandam. A., & Rajan, L. (2013). A conceptual framework of occupational stress and coping strategies. ZENITH International Journal of Business Economics & Management Research, 3(5), 154-172.

Al-Raqadi, A., Abdul Rahim, A., Masrom, M., & Al-Riyami, B. (2015). Learning quality management for ships’ upkeep and repair environment. Asian Social Science, 11(16), 196-218.

American Psychological Association. (2015). Stress in America: Paying with our health. News Press. Web.

Annamalai, S., & Nandagopal, R. (2014). Occupational stress: A study of employee stress in Indian ITES industry. New Delhi, India: Allied Publishers.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22, 309-328.

Britt, T., & Jex, S. (2015). Thriving under stress. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, K. M. (2015). Flexible work schedules, virtual work programs, and employee productivity (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. (UMI No. 3700954)

Cardoso, P. Q., Padovani, R., & Tucci, A. M. (2014). Analysis of stressors agents and stress expression among temporary dock workers. Estudos de Psicologia, 31, 507-516.

Caruth, G. D. (2013). Demystifying mixed methods research design: A review of the literature. Mevlana International Journal of Education, 3, 112-122.

Castillo-Montoya, M. (2016). Preparing for interview research: The interview protocol refinement framework. The Qualitative Report, 21, 811-830.

Cerasoli, C. P., Nicklin, J. M., & Ford, M. T. (2014). Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic incentives jointly predict performance: A 40-year meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 980-1008.

Cevenini, G., Fratini, I., & Gambassi, R. (2012). A new quantitative approach to measure perceived work-related stress in Italian employees. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 25, 426-445.

Cezar-Vaz, M. R., de Almeida, M., Bonow, C., Rocha, L. P., Borges, A. M., & Piexak, D. R. (2014). Casual dock work: Profile of diseases and injuries and perception of influence on health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11, 2077-2091.

Chen, M.-C., Huang, Y.-W., Hou, W.-L., Sun, C.-A., Chou, Y.-C., Chu, S.-F., & Yang, T. (2014). The correlations between work stress, job satisfaction and quality of life among nurse anesthetists working in medical centers in Southern Taiwan. Nursing and Health, 2(2), 35-47.

Crouch, M., & McKenzie, H. (2006). The logic of small samples in interview-based qualitative research. Social Science Information, 45, 483-499.

Crowe, S., Creswell, K., Robertson, A., Huby, G., Avery, A., & Sheikh, A. (2011). The case study approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11, 100-109.

Dwamena, M. A. (2012). Stress and its effects on employees’ productivity: A case study of Ghana ports and harbors authority (Master’s thesis, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology). Web.

Dworkin, S. L. (2012). Sample size policy for qualitative studies using in-depth interviews. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41, 1319-1320.

Emmel, N. (2013). Sampling and choosing cases in qualitative research: A realist approach. London, UK: Sage.

Flick, U. (2014). An introduction to qualitative research (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ford, J. K. (2014). Improving training effectiveness in work organizations. London, England: Psychology Press.

Frels, R. K., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2013). Administering quantitative instruments with Qualitative Interviews: A mixed research approach. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91, 184-194.

Fusch, P. I., & Ness, L. (2015). Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qualitative Report, 20, 1408-1416.

Grbich, C. (2013). Qualitative data analysis: An introduction. London, UK: Sage.

Griffiths, M. F., Baxter, S. M., & Townley-Jones, M. E. (2011). The wellbeing of financial counselors: A study of work stress and job satisfaction. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 22(2), 41-78.

Gupta, M., Kumar, V., & Singh, M. (2014). Creating satisfied employees through workplace spirituality: A study of the private insurance in Punjab (India). Journal of Business Ethics, 122, 79-88.

Hakanen, J. J., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2012). Do burnout and work engagement predict depressive symptoms and life satisfaction? A three-wave seven-year prospective study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 141, 415-424.

Hennick, M., Hutter, I., & Balley, A. (2011). Qualitative research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hesse-Biber, S. N. (2016). The practice of qualitative research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

King, N., & Horrocks, C. (2010). Interviews in qualitative research. London, UK: Sage.

Lam, C. F., & Mayer, D. M. (2014). When do employees speak up for their customers? A model of voice in a customer service context. Personnel Psychology, 67, 637-666.

Leon, M., & Halbesleben, J. (2013). Building resilience to improve employee well-being. In A. Rossi, J. Meurs, & P. Perrewe (Eds.), Improving employee health and well-being (pp. 65-79). Charlotte, NC: IAP.

Liu, J., Siu, O.-L., & Shi, K. (2010). Transformational leadership and employee well-being: The mediating role of trust in the leader and self-efficacy. Applied Psychology, 59, 454-479.

Lund, T. (2012). Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches: Some arguments for mixed methods research. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 56, 155-165.

Lyness, K. S., & Judiesch, M. K. (2014). Gender egalitarianism and work–life balance for managers: Multisource perspectives in 36 countries. Applied Psychology, 63, 96-129.

Lyons, J., & Schneider, T. (2009). The effects of leadership style on stress outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 20, 737-748.

Maran, D. A., Varetto, A., Zedda, M., & Ieraci, V. (2015). Occupational stress, anxiety and coping strategies in police officers. Occupational Medicine, 65, 466-473.

Marzec, M. L., Scibelli, A., & Edington, D. (2014). Impact of changes in medical condition burden index and stress on absenteeism among employees of a US utility company. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 8, 15-33.

Meško, M., Erenda, I., Videmšek, M., Karpljuk, D., Štihec, J., & Roblek, V. (2013). Relationship between stress coping strategies and absenteeism among middle-level managers. Management: Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 18, 45-57.

Michaelis, B., Wagner, J. D., & Schweizer, L. (2015). Knowledge as a key in the relationship between high-performance work systems and workforce productivity. Journal of Business Research, 68, 1035-1044.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, L. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Miller, T., Mauthner, M., Birch, M., & Jessop, J. (2012). Ethics in qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mosadeghrad, A. M. (2014). Occupational stress and its consequences: Implications for health policy and management. Leadership in Health Services, 27, 224-239.

Mullan, B. A. (2014). Sleep, stress, and health: A commentary. Stress and Health, 30, 433-435.

Naqvi, S. M. H., Khan, M. A., Kant, A. Q., & Khan, S. N. (2013). Job stress and employees’ productivity: Case of Azad Kashmir public health sector. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 5, 525-542.

O’Keefe, L., Brown, K., & Christian, B. (2014). Policy perspectives on occupational stress. Workplace Health & Safety, 62, 432-438.

O’Sullivan, E., Rassel, G. R., & Berner, M. (2008). Research methods for public administrators. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42, 533-544.

Robertson, I. T., & Cooper, C. L. (2010). Full engagement: The integration of employee engagement and psychological well-being. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 31, 324-336.

Roller, M. R., & Lavrakas, P. J. (2015). Applied qualitative research design: A total quality framework approach. New York, NY: The Gilford Press.

Saldana, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. New York, NY: SAGE.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Taris, T. W. (2014). A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. In G. Bauer & O. Hamming (eds.) Bridging occupational, organizational, and public health (pp. 43-68). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer.

Seidman, I. (2013). Interviewing as qualitative research: A guide for researchers in education. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Shaw, I., & Holland, S. (2014). Doing qualitative research in social work. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sherridan, C., & Ashcroft, K. (2015). Work-related stress: What is it, and what do employers need to do to address it. NZ Business, 29(4), 4-5.

Simon, N., & Amarakoon, U. (2015). Impact of occupational stress on employee engagement. Proceedings of 12th International Conference on Business Management, 1-14. Web.

Smit, N. W. H. (2014). Assessing work stressors, union support, job satisfaction and safety outcomes in the mining environment. Web.

Swanson, C. R., Territo, L., & Taylor, R. W. (2016). Police administration: Structures, processes, and behavior (8th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

The European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. (2014). Calculating the cost of work-related stress and psychosocial risks. Web.

Trivellas, P., Reklitis, P., & Platis, C. (2013). The effect of job-related stress on employees’ satisfaction: A survey in health care. Procedia–Social and Behavioral Sciences, 73, 718-726.

Truss, C., Alfes, K., Delbridge, R., Shantz, A., & Soane, E. (Eds.). (2013). Employee engagement in theory and practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

Vainio, H. (2015). Occupational safety and health in the service of people. Industrial Health, 53, 387-389.

Vaismoradi, M., Jones, J., Turunen, S., & Snelgrove, H. (2016). Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. Journal of Nursing Education and Practice, 6(5), 100-110.

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2007). The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management, 14, 121-141.

Yin, R. K. (2013). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). London, UK: Sage.