Introduction

The current work is based on the medical case of a 63-year-old patient without the previous medical history of breast cancer who was diagnosed with invasive ductal carcinoma. With the help of immunocytochemical methods, it was found that the tumour mass is oestrogen receptor-positive, progesterone receptor-positive and HER2 negative. After lumpectomy, the woman underwent chemotherapy, however, during this period, she suffered from bladder infections that required additional antibiotic therapy. The purpose of this essay is to investigate the pathophysiology of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer, the molecular basis of the therapeutic agents’ activities, their potential side effects and enterococcal virulence factors that provoke bladder infections.

Pathophysiology of Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer

The examination of physiological processes that result or associated with certain disease or injury is highly essential both for theoretical research concerning this medical condition and the definition of treatment methods. The contemporary understanding of the etiopathogenesis of breast cancer addresses the origin of invasive cancer through a substantive number of molecular alterations at the cellular level (Chalasani, 2019). The result of these alterations is breast epithelial cells that possess immortal features and are characterized by uncontrolled growth.

Genomic profiling has already demonstrated the existence of several discrete subtypes of breast tumour with distinct clinical behaviour and natural histories. The precise number of molecular alterations and cancer subtypes remains to be completely elucidated (Chalasani, 2019). In general, subtypes are characterized by the absence or presence of oestrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) (Chalasani, 2019). This differentiation provided the perception of breast cancer “not as a set of stochastic molecular events” but a limited range of separable disorders of distinct cellular and molecular origins (Chalasani, 2019, para. 3). Moreover, this approach has changed the understanding of breast cancer aetiology, its prevention and risk factors that appear according to the disease’s subtype. This view has substantially influenced breast cancer research and the strategies of treatment as well.

Every breast cancer subtype has distinct epigenetic and genetic aberration. According to The Cancer Genome Atlas Network, there are four main tumour subtypes – luminal A, luminal B, basal-like and HER2-positive breast cancer (Chalasani, 2019). HER2-positive cancer is characterized by the presence of HER2 and the absence of ER (Chalasani, 2019). It is insignificantly common though highly aggressive breast cancer subtype with high grade histology (Chalasani, 2019). This subtype presents a potential threat for African American ethnicity and women at a relatively young age. Basal-like breast cancer is an aggressive subtype with high mitotic rate and histology that is defined by the absence of ER, PR and HER2 (Chalasani, 2019). It is substantively virulent for premenopausal African American and young women as well. Luminal A and luminal B subtypes are generally similar; the main difference between them is the presence of HER2 in luminal B subtype and its absence in luminal A breast cancer (Chalasani, 2019). Invasive ductal carcinoma that 63-years-old patient was diagnosed with refers to luminal A tumour subtype.

Hormone receptor-positive breast cancer is the most widespread type of breast cancer around the world. From 60% to 75% of women who suffer from breast cancer have ER-positive cancer, and 65% of these oestrogen receptor-positive cancers are PR-positive as well (Burstein et al., 2014). Although hormone receptor-positive cancer is less aggressive in comparison with other subtypes and traditionally has a good prognosis, it frequently metastasizes via lymphatics (Chalasani, 2019). For a prevalent number of women with ER and PR-positive tumours, adjuvant endocrine therapy may be regarded as appropriate and highly effective. This medical treatment is a widely prescribed therapy in both developed and developing countries worldwide.

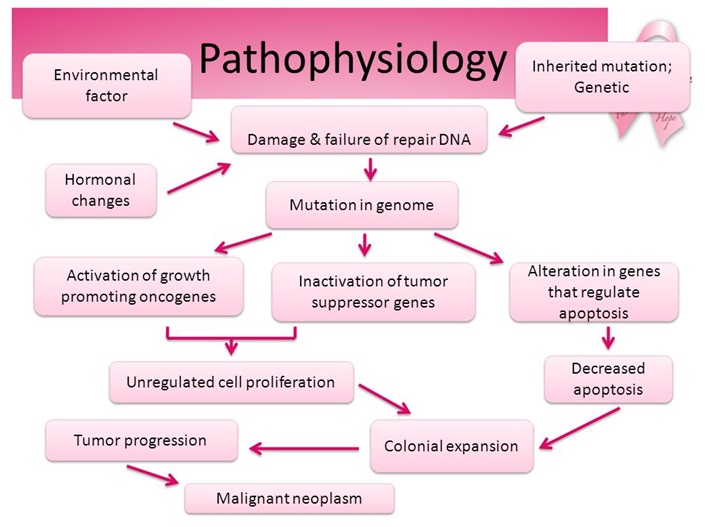

There are specific factors that may provoke molecular alterations at the cellular level and tumour growth. First of all, an environmental factor, hormonal change and inherited genetic mutations substantively influence the damage of DNA and the subsequent mutations in genome (Figure 1: Pathophysiology). Concerning the case of the 63-years-old woman’s invasive ducal carcinoma, age may be regarded as a considered factor that provoked the tumour progression. Although she did not have a previous medical history related to breast cancer, it is acceptable to suppose that she could experience hormonal changes due to pregnancy and menopause. Moreover, her underlying risk for breast cancer could be determined genetically in case if any of her relatives have had breast cancer as well. The cancerous mutation in genome has several consequences that inevitably result in tumour progression. The mutation leads to the activation of oncogenes that promote uncontrolled tumour growth, the inactivation of genes responsible for tumour suppression, and the alteration in apoptosis-regulating genes (Figure 1: Pathophysiology). These deteriorations of highly essential genes result in decreased apoptosis, unregulated cell proliferation, and successive tumour growth.

Treatment of Hormone-Dependant Breast Cancer

Aromastase Inhibitors

The treatment of hormone-dependent tumour requires a number of various drug strategies that include the use of aromatase inhibitors, selective oestrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) or other anti-estrogenic agents, for instance, fulvestrant. Estrogens are regarded as the significant elements for breast cancer growth for premenopausal and postmenopausal women as well. Although after menopause, the producing of estrogens in ovaries stops, peripheral tissues still have a substantial concentration of estrogens to stimulate tumour progression. Aromatase inhibitors are traditionally used for the treatment of ER-positive breast carcinoma all over the world as this enzyme decelerates oestrogen biosynthesis (Fujii et al., 2014). Endocrine therapy substantially reduces breast cancer-related mortality and the reoccurrence of the disease as well (Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group, 2014). There are two classes of inhibitors that are currently used in medicine for cancer treatment – nonsteroidal and steroidal compounds. Nonsteroidal inhibitors are highly effective in the suppression of urinary and plasma estrogens, while the steroidal substrate analogues, such as formestane and examestane, combat advanced disease.

However, the oestrogen receptor is not immune to mutations that play a highly significant role in the resistance to endocrine therapy. According to previous researches, acquired resistance to aromatase inhibitors has been detected in one-third of breast cancer patients (Alluri, Speers and Chinnaiyan, 2014). While the resistance to inhibitors is highly plausible for only 20% of women with early-stage breast cancer, it is inevitable in the case of metastatic disease (Ma et al., 2015). Genomic analyses of oestrogen receptor-positive tumours indicated a substantial number of mutated genes that influence the responsiveness of endocrine therapy.

Nevertheless, the therapy via the use of aromatase inhibitors has its adverse effects as well. They are frequently connected with poor drug adherence and high discontinuation rates within the therapy’s first year, as up to 50% of patients do not take aromatase inhibitors as prescribed (Irwin et al., 2014). As a result, they suffer from arthralgia that is defined as stiffness or pain in the joints.

SERMs

SERMs are defined as synthetic non-steroidal agents that exhibit various tissue-specific oestrogen receptor agonist and antagonist activities and are commonly used for the medical treatment of menopausal symptoms, osteoporosis and breast cancer. Its effectiveness is characterized by “the receptor conformation changes associated with that SERM’s binding and the subsequent effect on transcription” (Pinkerton and Thomas, 2014, p. 142). In clinical practice, the fundamental difference between SERMs is endometrial safety, and a lack of its safety may provoke a range of adverse effects. For instance, tamoxifen is marked by oestrogen receptor agonist activities in the uterus that result in a substantively increased risk of malignancy and endometrial hyperplasia (Komm and Mirkin, 2014). By contrast, bazedoxifene and raloxifene have a neutral effect on the uterus (Komm and Mirkin, 2014). Due to their long-term safety and efficacy, selective oestrogen receptor modulators are traditionally prescribed for patients who cannot tolerate other methods of treatment or have a potential risk of fracture due to continued therapy.

Fulvestrant

The use of aromatase inhibitors or selective oestrogen receptor modulators is defined as the most preferred approach to endocrine treatment for a prevalent number of patients who have hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. However, the patients’ tumours may progress in spite of the therapy or develop resistance. Fulvestrant is an anti-estrogenic agent or selective oestrogen receptor down-regulator that is characterized by high efficacy and activity for patients who have an untreated hormone receptor-positive breast cancer or previous hormonal therapy (Ciruelos et al., 2014, p. 201). The effectiveness of this drug was demonstrated in the metastatic and neoadjuvant settings, both alone and in combination with targeted drugs or anastrozole.

Moreover, according to clinical researches, 500 mg of fulvestrant is more effective in comparison with 250 mg of the same agent “without significant differences in the toxicity profile” (Ciruelos et al., 2014, p. 201). The presurgical data analysis reveals that the drug’s continuous dose-dependent effect on tumour biomarkers results in a significant reduction of estrogens (Robertson et al., 2014). Fulvestrant is an effective and safe drug for systematic therapy and it may be considered as a valid treatment option for hormone-sensitive breast cancer that has no substantial adverse effects in comparison with other therapies.

Bladder Infections and Additional Anti-Microbial Therapy

Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis are both frequent opportunistic pathogens and the inhabitants of the gastrointestinal tract. Enterococci are responsible for a wide range of various resistant to antibiotics and biofilm-associated infections such as urinary tract infections and the infections of surgical sites, bloodstream and wounds (Goh et al., 2017). The understanding of enterococcal pathogenesis and mechanisms of colonization are highly essential for the methods of treatment of these infections.

Virulence factors are defined by individual double mutants or deletion mutants of specific genes (Goh et al., 2017). According to Goh et al. (2017), the substantial number of infections is polymicrobial, “in which bacteria exist within mixed-species biofilms on host tissues or on medical devices and are more tolerant to antibiotic treatment or environmental stresses” (p. 1526). The clustering of microorganisms may provoke horizontal gene transfer and enhance their capacity to colonize, infect, and be preserved in patients (Goh et al., 2017). The resistance of Enterococci to relevant antibiotics, including vancomycin, daptomycin and ciprofloxacin, is currently regarded as a disturbing issue. In the case of resistance, the combination treatment when vancomycin and daptomycin substitute each other is recommended.

Conclusion

The examination of physiological processes that result or associated with certain disease or injury is highly essential both for theoretical research concerning this medical condition and the definition of treatment methods. Concerning breast cancer, there are several discrete subtypes of breast tumour with distinct clinical behaviour and natural histories. In general, subtypes are characterized by the absence or presence of oestrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). Hormone receptor-positive breast cancer (the presence of ER and PR and the absence of HER2) is the most widespread type of breast cancer around the world. There are specific factors that may provoke molecular alterations at the cellular level and tumour growth. Environmental factors, hormonal change and inherited genetic mutations substantively influence the damage of DNA and the subsequent mutations in genome.

The treatment of hormone-dependent tumour requires a number of various drug strategies that include the use of aromatase inhibitors, selective oestrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) or other anti-estrogenic agents, for instance, fulvestrant. Aromatase inhibitors are traditionally used for the treatment of ER-positive breast carcinoma all over the world as this enzyme decelerates oestrogen biosynthesis. Selective oestrogen receptor modulators are traditionally prescribed for patients who cannot tolerate other methods of treatment or have a potential risk of fracture due to continued therapy. Fulvestrant is an effective and safe drug for systematic therapy, and it may be considered as a valid treatment option for hormone-sensitive breast cancer that has no substantial adverse effects in comparison with other therapies. Enterococci are both frequent opportunistic pathogens and the inhabitants of the gastrointestinal tract. Bacteria are responsible for a wide range of various resistant to antibiotics and biofilm-associated infections such as urinary tract infections and the infections of surgical sites, bloodstream and wounds. Their virulence factors are defined by individual double mutants or deletion mutants of specific genes.

Reference List

Alluri, P. G., Speers, C. and Chinnaiyan, A. M. (2014) ‘Estrogen receptor mutations and their role in breast cancer progression’, Breast Cancer Research, 16(494). Web.

Burstein, H. J. et al. (2014) ‘Adjuvant endocrine therapy for women with hormone receptor–positive breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline focused update’, Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32(21), pp. 2255–2269. Web.

Chalasani, P. (2019) Breast cancer. Web.

Ciruelos, E. et al. (2014) ‘The therapeutic role of fulvestrant in the management of patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer’, The Breast, 23(3), pp. 201-208. Web.

Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) (2014) ‘Aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen in early breast cancer: patient-level meta-analysis of the randomised trials’, The Lancet, 386(10001), pp. 1341-1352. Web.

Fujii, R. et al. (2014) ‘Increased androgen receptor activity and cell proliferation in aromatase inhibitor-resistant breast carcinoma’, The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 144, pp. 513-522. Web.

Goh, H. M. S. et al. (2017) ‘Model systems for the study of Enterococcal colonization and infection’, Virulence, 8(8), pp. 1525-1562. Web.

Irwin, M. L. et al. (2014) ‘Randomized exercise trial of aromatase inhibitor–induced arthralgia in breast cancer survivors’, Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(10), pp. 1104-1111. Web.

Komm, B. S. and Mirkin, S. (2014) ‘An overview of current and emerging SERMs’, The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 143, pp. 207-222. Web.

Ma, C. X. et al. (2015) ‘Mechanisms of aromatase inhibitor resistance’, Nature Reviews Cancer, 15(5), pp. 261-275. Web.

Pathophysiology (no date). Web.

Pinkerton, J. V. and Thomas, S. (2014) ‘Use of SERMs for treatment in postmenopausal women’, The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 142, pp. 142-154. Web.

Robertson, J. F. R. et al. (2014) ‘A good drug made better: the fulvestrant dose-response story’, Clinical Breast Cancer, 14(6), pp. 381-389. Web.