Biographical Background

Rosa Mayreder was born in 1858 in Vienna, the capital of Austria, which, back then, was still a great power and one of the centers of Europe’s culture, science, and philosophy. Her father, a rich restaurateur, had no interest in educating his daughters, but, luckily for her, Rosa was only one of twelve siblings and managed to attend her brothers’ studies. Her acute interest in intellectual pursuits earned her some criticism from her family, who thought it was not a feminine quality (Leng 145). However, it did not dissuade her from developing her intellect and her taste for art. As Mayreder came of age, she became acquainted with many contemporary writers, artists, philosophers, and other intellectuals, both in person and through their works. The most notable of those were philosophers such as Ulrichs and Krafft-Ebings, who studied the issues of sexual identity and even approached what would later be codified as the gender-sex difference (Leng 146). Thus, as a young adult, Mayreder already had a good, if sometimes piecemeal education, a solid understanding of the contemporary philosophy of sex and gender, and deep dissatisfaction with women’s social status.

With these factors in mind, it should not come as a big surprise that Mayreder became a feminist – and one of the first ones in Austria at that. The key point of her feminist views was that society reduced women to performing very few roles – most notably, those of mothers and wives (Leng 148). She argued that, in order to develop their potential, women had to break free from such limitations and, by assuming the roles traditionally reserved for men, escape the “teleological fate of their sex” (Leng 149). In order to promote her feminist views, she wrote a number of influential papers over the years, engaging deeply with contemporary philosophy as well as the German literary tradition (Looft 73). Her intellectual contribution did not remain unnoticed, and, in 1907, she became the only woman among the founding members of the Sociological Association on Vienna. In recognition of her work and influence, in 1928, the Vienna city council made her an honorary citizen. Mayreder passed away in early 1938, mere months before the German Anschluss of her home country.

While most famous for her literary and philosophical works, Mayreder was also a distinguished painter in her own right. As befitted a girl from a well-to-do 19th-century family, she received formal instruction in painting and carried the interest in visual arts through her entire life. This is clear from the fact that, in 1893, she founded a special art school for women and girls and continued to support it throughout the years (Hochreiter 103). In a way, it was an extension of her philosophical views, as evident from the fact that other founders were also prominent feminists, such as Marianne Hainisch and Olga Prager (Hochreiter 103). As a painter herself, Mayreder became the first woman to be accepted into the Aquarellist club, which speaks of recognition among her contemporaries. While it was not necessarily the rule, Mayreder could use paintings in the same way as she used language- to provoke discussion of women’s social status and the roles allotted to them. This was most likely the case with her 1891 painting named A Garden Still Life with a Kitten.

Artwork Analysis: Gardening with a Kitten

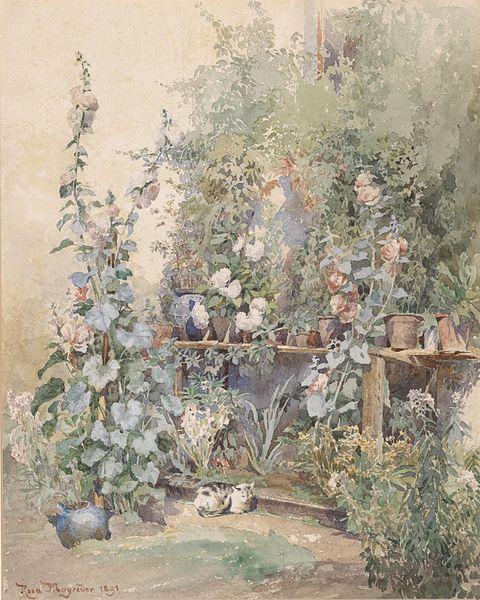

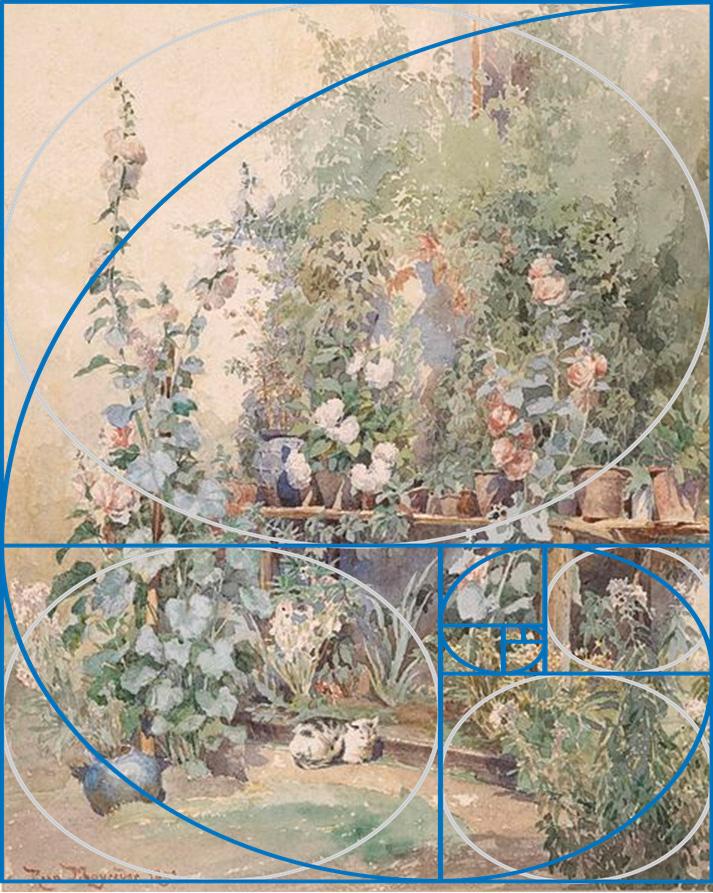

As the name suggests, A Garden Still Life with a Kitten is a still life painting, a watercolor on paper. It depicts a small garden next to a house wall with a variety of plants in pots and a little kitten among them. In terms of composition, the painting’s center of gravity on a horizontal axis is closer to the right side, as the left one is almost empty, save for one large plant (Image 1). The horizontal shelf housing most of the pots separates the painting vertically into two uneven parts, which relate to each other as roughly 1.6 to 1 (Image 2). The left part of the lower half, with a singular large plant and a kitten, and the right part, with a plant at the forefront, also relate to each other similarly (Image 2). The pattern continues with the plant on the lower right and the space above it, and so forth. This approach clearly indicates the use of the golden ratio to arrange the pictorial space in a balanced and visually pleasing way, in which Mayreder definitely succeeds.

In terms of color, the painting is dominated by warm browns and yellows of the ground and the wall and pale greens of the various plants. An occasional sprinkle of pink flowers prevents it from being visually monotonous (Image 1). The painting positively bathes in light, which falls from the upper left corner and is so intense that there are barely any shadows. It is the lighting that is primarily responsible for the tone, as even the large leaves, which would normally be dark green, are almost white under the intense light (Image 1). That to the color palette, the painting radiates the sensation of a hot and sunny day.

The brushwork is brisk, evocative, and precise, outlining the painting in sufficient detail and generally avoiding broad and loose strokes. In some parts, most notably the upper left, the strokes can be relatively loose, as if to imitate the leaves blurring against the bright yellow wall in the intense sunlight (Image 1). However, most of the painting uses short and precise strokes that outline the pots, the plants, and the titular kitten in considerable detail.

When it comes to the subject matter, one may interpret A Garden Still Life with a Kitten as a statement on the limited opportunities available to women in Mayreder’s time. First of all, attending to a small garden would be seen as an appropriate and characteristically feminine occupation at the time. Given Mayreder’s opposition to restraining women to a few domestic occupations, a feminist subtest is not unlikely (Leng 148). The garden pots on the shelf are cluttered and overlap with each other, as if the unnamed, presumably female gardener tried to fit as much of them as possible into a small space (Image 1). This may suggest that, with the social limitations imposed on the woman in question, gardening remains the only venue of realizing her potential, which is why she pursues it with such vigor. In this respect, one may see A Garden Still Life with a Kitten as a pictorial equivalent to Steinbeck’s “The Chrysanthemums.” Finally, the plants are growing and intertwining wildly and out of control, suggesting that the garden’s confines are as limiting to them as the patriarchal social mores are to women.

Personal Response & Comparison

My personal response to A Garden Still Life with a Kitten is that it is a very competent watercolor painting, which is more important as a work belonging to Mayreder than on its own merits. The painting hardly resembles the bold strokes and blurred lines of impressionism, which was its contemporary, and is fairly academic in terms of style. Apparently, unlike her thinking and progressive principles, Mayreder’s paintings were hardly revolutionary in terms of style, technique, or composition. It makes sense, given that Mayreder received training in painting since she was a child because it was seen as an appropriate occupation for a young lady. As a result, in Mayreder’s crusade to escape the “teleological fate of their sex,” painting was the means rather than the goal (Leng 149). Instead of trying to revolutionize the ways in which the paintings are created, Mayreder tried to use fairly traditional painting techniques to make a bold statement on social matters. In other words, A Garden Still Life with a Kitten is most notable for being the work of Mayreder as a feminist painter rather than a stepping stone in art history.

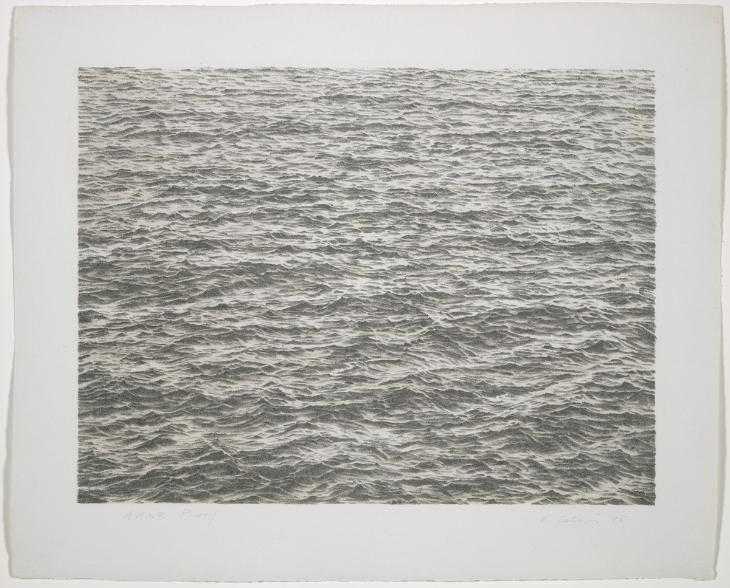

In order to better understand the painting’s characteristic features, one may compare A Garden Still Life with a Kitten to Ocean, a work of another female artist Vija Celmins. The comparison would be a study in contrasts, but it is exactly what makes it worthwhile. In terms of genre, Ocean is not a still life but a landscape – or, rather, a seascape painting (Image 3). The color palette is dominated by iron greys, and the light falling from above does not do anything to make it lighter (Image 3). Unlike the carefully crafted golden ration composition of Mayreder’s painting, Ocean has nothing for the eye to catch onto – it is just an endless, uniform expanse of cold water. The brushwork is meticulous and thorough, and even the smaller waves in the upper half of the painting are drawn in just as much detail as those at the forefront (Image 3). In other words, Ocean is as different from Garden Still Life with a Kitten as possible while the latter is concrete, the former is abstract to the extreme.

This comparison demonstrates the difference in the approach taken by both painters –and, by extension, allows understanding Mayreder’s work better. Celmins’ painting is noticeably abstract and apparently devoid of any political, social, or personal statement whatsoever. It lines up well with Celmins’ own statements – as the author says herself, she does not use her works to reveal her feelings or what she thinks about the current President (“Explore the Art”). In contrast, Mayreder chooses the genre, composition, and subject matter in a way that makes it very easy to see a political statement in A Garden Still Life with a Kitten. If one knows about her feminist convictions – which, in any case, are a more famous part of her life – it becomes fairly simple to interpret the painting as a statement on women’s social status. Hence, the comparison between Mayreder’s A Garden Still Life with a Kitten and Celmins’ Ocean reveals how artistic choices may facilitate or negate the possibility of making a statement out of a piece of art.

Works Cited

“Explore the rat of Vija Celmins.”Tate.

Hochreiter, Susanne. “‘What Women Are Will Not Be Known Until They Are No Longer Told What They Should Be’: Rosa Mayreder and the So-Called ‘Frauenfrage’ In Viennese Modernity.” Crime and Madness in Modern Austria: Myth, Metaphor, and Cultural Realities, edited by Rebecca S. Thomas, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2008, 94-116.

Leng, Kirsten. Sexual Politics and Feminist Science: Women Sexologists in Germany,1900–1933. Cornell UP, 2018.

Looft, Ruxandra. “Intertextuality as Power: Rosa Mayreder’s Response to Goethe’s Faust and the Cult of Male Genius.” Journal of Austrian Studies, vol. 51, no. 2, 2018, pp. 73-88.