Introduction

On April 1900, Paris held a world trade fair, which brought together people from different consumer markets to celebrate past technological achievements and gain an insight into potential futuristic developments.

The trade fair portrayed the potential of the then and future civilizations to deploy technology, creativity, and innovation to create more consumables to better the life of the future generations.

The trade fair set the foundation for availing more products and services in the marketplace. Primarily, products are availed in the markets for consumers to buy and the buying behaviors are subject to various factors.

The organizations’ ability to generate sales revenue is greatly influenced by their capacity to influence the consumers’ buying behavior. However, Grant, Clarke, and Kyriazis (2013) affirm that the consumer buying behavior is complex because it is influenced by internal and external factors.

The academic trend in studying buying behaviors views them as personality disorders. This approach holds that consumers purchase products compulsively due to anxiety or depression associated with not buying the same products.

This research takes a different approach of studying the consumers’ buying behaviors from what is in the current academic trend. Rather than studying buying behaviors as compulsive disorders, it studies them as lifestyles driven by societal pressures.

Without these behaviors, people are rejected from a given societal class. Compulsive behavior varies according to various demographic differences. For example, women are highly compulsive buyers as opposed to men. However, this conclusion is based on what the society considers as abnormal or normal.

For a considerable duration, some societies have conceptualized normality in terms of men’s behaviors. This perspective suggests that if compulsive buying behavior is more prevalent amongst women as compared to men, it is considered abnormal. This paper refutes such as a conclusion.

This paper’s aims and objectives are three-fold. It conducts a systematic review of the current literature on personality and personality disorders literature coupled with how they contribute to the compulsive buying behaviors. The second objective entails an investigation of whether compulsive behavior is a personality disorder.

Thirdly, it studies the possibility of compulsive behavior being a lifestyle as opposed to a personality disorder. The study has significant contributions to the academic research on consumer buying behaviors.

The dissertation overlooks different factors increasing the prevalence of compulsive buying behavior (CBB) or aggravating it. Stressing on some of these factors is necessary since it has not been projected in previous studies of compulsive buying behavior. Therefore, it sets forth a different paradigm of understanding CBB.

This aspect offers a different way for formulating policies and programs for industries for promoting their products by designing and marketing products and services to meet the lifestyles leading to purchases. Shopping is an essential component of daily life (Li, Unger & Bi, 2014).

However, purchasing without considering its consequences is impulsive, which may lead to anxiety and unhappiness. The main challenge arises when it becomes frequent and uncontrollable.

The paper is organized into four sections. Section 1 reviews the available literature on compulsive buying behaviors and their association with personality and personality disorders. Section 2 discusses the research methodology. Section 3 presents the results and findings of the research study.

Literature review

Compulsive buying behavior

Shopping entails an important aspect of all people coupled with the economy. While this aspect is a normal behavior, challenges emerge when people overindulge in it without paying attention to its consequences. More focus in buying behaviors has been on compulsive purchasing as it has negative consequences for individuals.

Neuner, Raab, and Reisch (2005) support this assertion adding that more focus on research on compulsive purchasing behavior is due to the view that it is more prevalent among consumers of all demographic differences.

Marketing research focuses on understanding the people’s shopping culture and sought after products and services so that its research and design can focus on these attributes to attract high sales. Indeed, much of the work on this topic has been conducted from marketing research perspective.

Dittmar, Long, and Bond (2007) suggest that people having compulsive purchasing behavior have high probabilities of experiencing strong buying desire, which overcomes the harms of the compulsion on financial coupled with social aspects of life.

Faber and O’Guinn (1992) add that such people do not possess the mechanism for differentiating between abnormal and normal buying behaviors. The question then remains as the origin of such behaviors. Some studies cite compulsive buying as a psychological problem.

Traditionally, psychologists have viewed personality as a distinction criterion for people’s behaviors.

Behaviorism encompasses one of the important schools of thought explaining why people engage in some behaviors and not others. The big five traits theory also explains the differences among people indecision-making.

Experimental analysis of people’s behaviors suggests that interactions with the environment influence one’s personality. However, Goodstein and Lanyon (2009) argue that internal thinking processes coupled with feelings are critical in influencing and structuring of people’s personalities.

Studying compulsive behavior from the perspective of behavioral psychology introduces some challenges depending on the psychological theoretical arguments used. For example, traditional psychologists tested how behaviors influence personality through animal experimentation.

They believed that animals and people shared similarities in terms of the learning process. However, as Goodstein and Lanyon (2009) argue, human learning processes are progressive.

The psychological behavioral theory explains the dynamic process of obtaining the new learning, which shapes one’s personality. After learning behaviors, Goodstein and Lanyon (2009) suggest that before inflexibility of the personality, people can experience emotional responses towards a given situation, thus causing a personality change.

However, as learning continues, it slows down the personality, thus causing stabilization. This assertion implies that people experience stable responses towards a give environmental stimulus (Stricker, Widiger & Weiner, 2003).

Influenced by this pedagogy, marketers deploy classical conditioning to enhance the consumption of their products. This aspect explains the divergent views on how conditioning influences behaviors. Neuner et al (2005) argue that emotions do not affect operant conditioning (behaviors).

Behaviors should be studied from paradigms of environmental influences. Psychological behaviorism holds that classical coupled with operant conditions play significant roles in influencing people’s behaviors (Pachauri, 2001).

Several factors may contribute to people’s emotional responses. These constitute the thoughts, beliefs, and perceptions affecting people’s emotional responses to the specific stimulus. Physiological behaviorism links emotions demonstrated by individuals with responses to the biological and environmental stimuli.

These emotions can be affirmative or negative toward different stimuli. For example, a positive pulse to a food stimulus or a negative emotion in response to the stimuli causes dislike and unwanted feeling. This aspect suggests that microtonal responses can help in increasing a purchasing behavior of a given products.

Li et al. (2014) define compulsive buying behavior as chronic tendency for purchasing products and services in response to negative conditions and feelings. The behaviors encompass an unconditioned response towards desires for goods or services and feelings of depression due to anxiety.

This aspect implies that the desire to purchase specific types of services or goods leads tithe development of compulsive behavior. The absence of these products or services induces stress or anxiety, which induces the compulsive buying behavior.

The five-personality dimension theory may also influence people’s behaviors, viz. the compulsive purchasing behavior. Indeed, Mueller, Mitchell, Claes, Faber, Fischer, and De Zwaan (2011) believe that personality plays important roles in influencing compulsive buying behavior.

Personality refers to “the sum total of ways in which an individual reacts and interacts with others” (Goodstein & Lanyon, 2009, p.291). It is measured by the traits that people exhibit. Research on personality in an organizational context has focused on labeling various traits, which describe employees and customer behaviors.

Some of the personality traits that have been established by various researches as having the ability to influence the behavior of people include ambition, loyalty, aggressiveness, agreeableness, submissiveness, laziness, assertiveness, and being extroverted among others.

Kihlstrom, Beer, and Klein (2002) posit, “Neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness comprise the big five personality traits” (p. 84). These traits can define factors characterizing consumer behavior as a personality type.

Literature considering roles of big five-personality traits theory in compulsive buying theory depicts incompatibilities in their results. However, consciousness encompasses an important trait, which can explain the differences in compulsive behaviors among different consumers.

Mueller et al. (2011) argue that although consciousness may be important in explaining differences in consumption behavior, which is important in predicting compulsive buying behavior, neuroticism does not relate to the behavior.

Borrowing from the work of Otero-López and Pol (2013), consumers fall into three groups, viz. high, medium, and low propensity in terms of their buying behaviors. According to Kihlstrom et al. (2002), the group “having the highest propensity possesses the highest levels of neuroticism and lowest consciousness” (p. 85).

The group also features the highest level of neuroticism, which includes anxiety, depression, and impulsiveness. Conversely, the group has relative to medium and low compulsive buying behaviors. Propensity groups have the weakest extraversion assertiveness, positive emotions, and self-consciousness.

Compulsive buying behavior: a personality disorder

Compulsive purchasing behavior encompasses an excessive dysfunctional consumption behavior, which aggravates people’s lives emotionally, financially, and mentally (Koran, Faber, Aboujaoude, Large & Serpe, 2006). Compulsive buying behavior manifests itself through psychological problems like depression and anxiety.

This aspect makes theorists like Faber and O’Guinn (1989) to consider it as a personality disorder. Personality disorder describes perennial maladaptive ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving amongst individuals.

However, Dittmar et al. (2007) argue that in defining compulsive buying behavior, it is critical to recognize that all disorders and perceptions of abnormality have cultural norm influences apart from considering disorders, which can be managed clinically.

The 2013 version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) classifies disorders into five annexes. Personality disorders fall under annex 2 in cluster C.

This group comprises disorders like depression and schizophrenia. It also entails less maladaptive disorders characterized by anxiety and dependent personality or obsessive-compulsive disorders. In the manual, compulsive buying behavior does not appear.

Despite the non-inclusion of compulsive buying behavior in the list of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, many psychologists contend that it should fall under the anxiety personality category due to its characteristics of anxiety coupled with negative feelings amongst people suffering from it.

However, this contention attracts controversies. For example, Li et al. (2014) argue that the behavior encompasses an obsessive-compulsive disorder since it has symptoms similar to it. Black (2001) suggests that it becomes compulsive due to lack of impulsive control.

Studies like Faber and O’Guinn (1992) attempt to highlight the relationships between compulsive buying behaviors and personality traits coupled with family lifestyles. This aspect suggests that the literature on compulsive buying behavior mainly focuses on analyzing it as a personality disorder.

An important gap exists in the attempt to relate the behavior with people’s lifestyles.

The current research approaches the problem of compulsive buying behavior as a lifestyle problem rather than a personality disorder. In achieving this concern, it is also important to study it from the pedagogy of obsessive compulsion.

Indeed, studies based on self-reports indicate that compulsive buyers experience similar symptoms to people with obsessive-compulsive disorder. This aspect includes high anxiety and stress that eventually lead to buying unneeded goods with anticipation for the reduction of negative feelings.

The satisfaction of desires influences anxiety and stress levels for a limited period so that compulsive buying becomes a repeated action. This aspect suggests relationship between compulsive buying behaviors with obsessive-compulsive behaviors.

People suffering from compulsive disorders have possibilities of having experienced situations in life, which led to mistrusts of their priorities coupled with their abilities. The obsessive-compulsive disorder is conceptualized from the paradigms of pursuance of eliminating the anxiety and stressful thoughts in executing certain individual acts.

Similarly, experiencing anxiety, depression, and stress are typical symptoms of compulsive buying behavior leading to the development of the urge to engage in compulsive buying. Faber and O’Guinn (1992) argue that this behavior is an abnormal consumption behavior.

It is abnormal to the extent that after purchasing to reduce stress and negative experiences, people often regret due to its repercussions like ensuing financial challenges.

Black (2001) suggests that for persons with the compulsive behavior disorder, their attention and thoughts give rise to anxiety and compulsions to reduce discomforts associated with failure to purchase products and services they desire urgently.

Obsessions entail negative feelings experienced by people before they engage in compulsive behavior in a bid to reduce anxieties, which encompass feeling of guilt for not engaging in a given act. Amid the established relationship between obsessive behavior and compulsive behaviors including compulsive buying behavior, Koran et al. (2006) classify it under impulsive control disorder.

People become susceptible to impulsive control disorder when they cannot control different urges. Koran et al. (2001) assert that people with compulsive buying disorder often think about shopping as opposed to thinking about its consequences or the objective of purchasing products and services.

For example, if a woman purchases cosmetics and clothing in a bid to satisfy her self-esteem, she may do so without thinking about this objective. It is also impossible to recognize that the buying behavior subjects her to vulnerabilities of suffering from compulsive buying.

This aspect suggests the importance of developing an appropriate scale for measuring compulsive purchasing behavior so that individuals can know when developing the problem.

Faber and O’Guinn (1989) made one of the earliest attempts to develop a scale for measuring compulsive buying behavior. The scale aimed at differentiating compulsive buyers from non-compulsive ones.

Attempts have been made to improve on the scale by incorporating mechanisms for identifying the attitudes toward product categories, processes of acquisition, and post-purchase feedbacks like positive or negative emotions as remorse after spending.

The most recent edition of the scale assesses the spending patterns coupled with behaviors, emotions, and feelings of people towards the desired products and process of acquisition.

Indeed, finance management through cash or credit cards constitutes some of the good examples of progressive precision in conceptualizing the compulsive buying disorder.

The Faber and O’Guinn (1989) scale for differentiation of compulsive buyers from non-compulsive buyers has some limitations. It entails a binary approach to measurement, which introduces challenges of measuring the propensity of the behavior.

However, the scale is crucial as it forms the foundation for the development of scales for measuring people’s compulsive buying behavior. For example, Edwards (1993) developed a scale for measuring the behavior based on Faber and O’Guinn’s scale.

Through the incorporation of spending behaviors as the dependent variable, the scale permits researchers to rate compulsive buying behaviors depending on their propensity. It classifies consumption behaviors into non-compulsive, low compulsive, medium compulsive, and high compulsive (Edwards, 1993).

The compulsive spending model identifies five factors related to compulsive purchasing behaviors. These are the “tendency to spend, compulsion to spend, feeling about shopping and spending, dysfunctional spending, and post-purchase guilt” (Koran et al. 2006, p. 1810).

From the 1980s, there has been an incredible scholarly research on compulsive spending behavior among consumers. For instance, Koran et al. (2006) argue that more than 5 percent of Americans are dealing with compulsive purchasing behavior.

Kukar, Ridgway, and Monroe (2009) reckon that the trend has now increased by about 4 percent to stand at more than 8.5 percent. However, there is no scholarly contention on factors leading to the increasing compulsive buying behavior among the Americans and other people across the globe.

Almost all researches on this subject deploy personality disorder to construct their hypothesis. This aspect excludes many other factors like lifestyles, which may account for the increasing behavior.

Irrespective of the improvements in the mechanisms of detecting mental disorders, the conceptualization of the disorder is incomplete (Li, Unger & Bi, 2014). For example, the definition of normal and abnormal behaviors is not straightforward.

Gaps remain on what amounts to a normal consumption behavior (Freshwater, Sherwood & Drury, 2006). Parts of these gaps are due to the view that people’s behaviors are subject to culture and living styles, but not necessarily a mental disorder.

The latest edition of the DSM-IVTR is composed of five axes for diagnosis based on the Western masculine ideals for a ‘healthy” person. It is likely to define the normal typical behavior of people, especially women, from other cultures as the abnormal behavior (Neuner, Raab & Reisch, 2005).

In such cultures, their behaviors are considered as normal in all aspects as they fit within their norms and cultural value systems. This aspect suggests that what amounts to a normal behavior in a multicultural context is a contentious issue.

Compulsive buying behavior varies with respect to different demographic characteristics of people. For example, it varies according to gender with women having high prevalence levels for the behavior (Maraz et al., 2014).

This assertion confirms the validity of an earlier study by Neuner et al. (2005), indicating higher prevalence levels for the behavior among women as compared to men.

However, Koran et al. (2006) hold that compulsive purchasing transcends gender and it can be viewed as a common personality disorder affecting women and men in equal thresholds. These discrepancies may be accounted for by the perceptions of normal and abnormal behaviors.

For example, masculine purchasing behavior may be labeled normal while feminine purchasing behaviors are labeled abnormal. Methods and theories for measuring prevalence may also have prejudices in terms of what amounts to a normal behavior.

Amid the discrepancies of the prevalence of compulsive buying disorder, an important interrogative explains the different prevalence levels. Eren, Eroglu, and Hacioglu (2012) suggest that women are one and a half times more likely to experience anxiety disorders as compared to men.

The comorbidity of the disorder arises due to the women’s position in society, which is characterized by power imbalances. For example, discrimination against women exposes them to threats of chronic anxiety disorders.

Apart from gender, inconsistency in research on compulsive buying behaviors exists based on other demographical dimensions like age and income levels.

For instance, Black (2001) found a negative correlation between income and compulsive buying density. Conversely, Mueller et al. (2011) found “no relationship between income and compulsive buying behavior” (p. 1310).

Compulsive buying behavior varies according to the state of people’s development. For example, Koran et al. (2006) estimated that 6% of the Americans are likely to consume compulsively. In Germany 5 to 7 percent of the population engages in compulsive buying (Mueller.et al., 2011).

Does this suggest that in Eastern countries people do not buy compulsively? Arguably, inadequate research on such nations and cross-cultural differences among consumers may lead to the attribution of higher compulsive buying to Western nations than in Eastern nations like China.

Indeed, the current literature on compulsive buying documents minimal research based on developing countries like those located in Asia.

The few scholarly researches on this topic in developing nations deploy theories and scales used in similar studies in the Western nations like Germany and the US amid differing lifestyles and ways of doing business.

For example, Eastern nations and Western nations have differing methodologies for paying, differing approaches in making shopping decisions, and differing consumer cultures.

Stemming from the arguments developed in this section, it is important to study compulsive buying behaviors depending on cultural characteristics of the population and using a specific methodology applicable to a given nation or region.

Considering that the majority of the researches in this topic base their hypothesis on compulsive buying behavior as a personality disorder, this research seeks for an alternative explanation of the behavior. It studies it as lifestyle challenge facing consumers in China.

Methodology

Research design

This research seeks to explore the compulsive buying lifestyle amongst consumers. The study’s findings will provide insight into the consumers’ purchasing behavior. Therefore, the research is exploratory in nature.

Saunders, Thornhill, and Lewis (2009) accentuate that exploratory research design enable researchers to undertake preliminary investigations in areas that have not been characterized by intensive research.

Subsequently, exploratory research leads to the generation of new insights on the phenomenon under investigation (Blanche, Durrhem & Painter).

The research study is based on a qualitative research design, which acts as the framework that guides the researcher in answering the research question. The qualitative research design was selected in order to generate adequate data from the field in order to support the research study.

Moreover, the choice of qualitative research design was further informed by the grounded theory. Strang (2015) defines the grounded theory as ‘the discovery from data systematically obtained from social research with the aim of generating or discovering a theory’ (p.449).

Alternatively, the grounded theory design involves a systematic and qualitative procedure that enables researchers to develop a practical theory that elucidates the phenomenon under evaluation at a conceptual level.

By adopting the grounded theory design, the researcher will be able to understand the social and cultural factors associated with the research topic. Subsequently, the research study will be adequately enriched. Additionally, the choice of qualitative research design is further based on the need to generate gather relevant data from the field.

Andrew (2004) content that ‘qualitative research process involves emerging questions and procedures, data typically collected in the participant’s settings, data analysis that builds inductively and interpretations of the meaning of the data’ (p.46).

Therefore, the qualitative research design enabled the researcher to derive data from the natural setting hence improving its credibility and validity of the research findings. The concepts of validity and credibility are some of the critical determinants of the relevance of research findings.

Population and sampling

In order to improve the capacity of the research study to enhance the consumer behavior theory using the grounded theory design, the researcher appreciated the importance of effective identification of study population. The study population was comprised of individual consumers from cultural and social backgrounds.

The study population was comprised of consumers of American, Iranian, Chinese and Italian consumers. The decision to select respondents from diverse cultural backgrounds was informed by the need to understand the variation with reference to consumer behavior across different cultural backgrounds.

Consequently, the study’s capacity to further explain the impact of cultural and social dimensions between Westerners and Easterners consumers on compulsive buying behavior was improved considerably.

The researcher recognizes cost as a major determinant in conducting the research study. In an effort to minimize the cost of conducting the research study, the researcher integrated the concept of sampling, which entails constructing a subset from the identified study population.

The study sample was constructed using the simple random sampling technique in order to minimize the occurrence of bias in constructing the sample study. Using the simple random sampling technique, the researcher provided all the subjects in the identified study population an opportunity of being included in the research study.

Thus, the sample was representative of the target population. Integrating the sampling technique made the study to be manageable by minimizing the amount of time and finances required to undertake the study.

Furthermore, the simple random sampling technique made the study to be representative of the prevailing consumer behavior (Scott, 2011). The research sample was comprised of 14 respondents.

Fourteen [14] of the respondents were Chinese, 6 female and 4 male respondents. Conversely, two of the respondents were American men, while the others included one Iranian woman and one Italian woman.

Data collection and instrumentation

The researcher understands the fact that the data collected directly influences the research findings. Thus, to improve the research findings, the study is based on data collected from primary sources in order to generate research data from the natural setting.

The primary method of data collection mainly involved conducting interviews on the respondents included in the study sample. The researcher selected the interviewing technique as the method of data collection in order to conduct an in-depth review of the compulsive buying behavior amongst consumers.

Adopting the interviewing technique provided the researcher an opportunity to probe further on research topic hence improving the quality of the data collected.

Interviews with the selected respondents were conducted through telephone in an effort to minimize the cost of the research study. The telephone interview was based on a number of questionnaires were designed in order to guide the researcher in the interviewing process.

The questionnaires were open-ended in nature. Adoption of the open-ended questionnaires provided the respondents an opportunity to answer the questions freely by providing their opinion. Moreover, the open-ended questionnaires limited the likelihood of the researcher influencing the response provided by the respondents.

The researcher ensured that the open-ended questionnaires were adequately reviewed in order to improve the respondents’ ability to understand. The questionnaires acted as the data collection guide. During the interviewing process, the researcher reviewed the respondents’ demographic characteristics.

This was achieved by evaluating their age, gender, disposable income, social status, and family and relationship aspects. Moreover, the researcher reviewed the respondents’ buying behavior such as their methods of payment on purchases, amount of their shopping, and the reason for shopping.

In order to improve the relevance of the data collected, the researcher further assessed the respondents’ product usage behavior. This was attained by asking the respondents whether they used the products after purchasing and if not what they do with the product.

By reviewing this aspect, the researcher was able to generate insight into the compulsive buying behavior amongst consumers characterized by diverse cultural and social backgrounds.

For example, the researcher was able to evaluate the consumers’ decision to increase or decrease the purchase of a particular product and the motivation for such behavior. Integrating such aspects in the research process enabled the researcher to undertake an extensive comparison of the compulsive consumer behavior.

A recorder was used in storing the responses obtained from the field.

Data analysis and presentation

The data collected from the field was analyzed qualitatively. However, the researcher integrated different data analysis and presentation tools. The researcher adopted tabular data presentation by organizing the research data into rows and columns. The main data analysis and presentation tools adopted include graphs, charts and tables.

Furthermore, the researcher also adopts the concept of textual presentation, which entails using statements comprised of numerals in order to explain the research findings effectively. By adopting the textual presentation technique, the researcher has been able to present the collected research data in the expository form.

The researcher was of the view that integrating these tools would have contributed towards the effective analysis of the descriptive research data obtained from the field. Moreover, the aforementioned data presentation methods played an essential role in improving the target audience ability to understand and interpret the data collected.

Ethical issues

In the course of collecting data from the field, the researcher took into account diverse ethical issues. The objective of taking into consideration such aspects was informed by the need to improve the rate of the selected respondents participating in the research study (Finlay, 2006).

First, the researcher ensured that that the selected respondents were adequately informed that the research study was aimed at adding new ideas/insight to the consumer behavior theory. Thus, the purpose of the study is academically inclined.

Therefore, the researcher was able to obtain informed consent in addition to eliminating any form of suspicion from the respondents. Moreover, the researcher provided respondents with an opportunity to pullout of the research study without any negative repercussions.

Moreover, the researcher observed the participants’ privacy during the research. Additionally, the researcher desisted from any form of coercion during the study process. Consequently, the respondents contributed freely in the study.

Results and findings

The study showed the existence of significant differences in compulsive buying behavior amongst consumers of different cultural and social characteristics. One of the most notable issues on compulsive buying behavior is that it extends beyond culture.

On the contrary, the study showed that the consumers’ compulsive buying behavior is greatly influenced by diverse demographic characteristics. Amongst the most notable factors that lead to the development of compulsive buying behavior entails the consumers age, gender, mood, and level of disposable income.

The study further shows that these aspects influence the consumers’ compulsive buying behaviors irrespective of their cultural and social backgrounds.

Moreover, the study showed that individuals characterized by compulsive buying behavior mainly indulge in such a behavior due to external pressures, such as the perception by the society and family members.

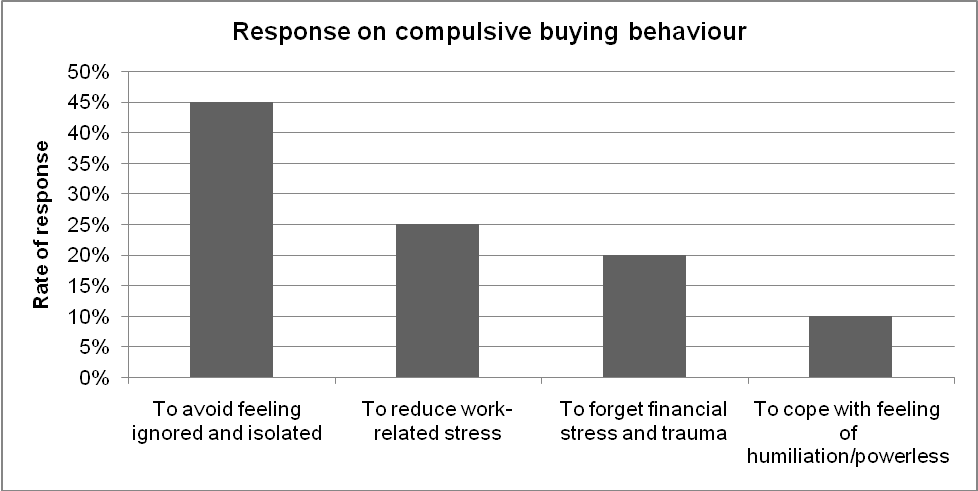

Forty-five percent [45%] of the respondents of the respondents interviewed were of the opinion that they engage in compulsive buying behavior in an effort to avoid being ignored and isolated by family members and the society.

Conversely, 25% of the respondents were of the opinion that they engage in compulsive buying behavior in order to reduce work-related stress while 20% of the respondents said that their compulsive buying behavior has been motivated by the need to forget their financial loss or trauma.

Moreover, 10% of the respondents were of the opinion that they engage in such behavior in an effort to compensate or cope with the feeling of being humiliated, powerless or having a faded role. The graph below illustrates the variation in the respondents’ opinion on their motivation towards compulsive buying behavior.

Discussion

Several studies confirm multi-dimensional aspects of compulsive purchasing behavior. Compulsive buying behavior is extensively influenced by personal and environmental characteristics. Faber and O’Guinn (1992) note that buyers can be grouped into different scales.

A Canadian measurement scale for compulsive purchasing behaviors identified three main dimensions of the behavior, viz. spending tendency, reactive aspects, and guilt after purchasing. The findings of the study conducted affirm that the compulsive buying behavior is not subject to the consumers’ cultural backgrounds only.

On the contrary, other individual traits are central determinants in the development of compulsive buying behavior. This shows that individuals’ personality is a critical determinant in the development of compulsive buying behavior.

Traditional behavioral theories postulate that individuals’ personality is due to the interaction between an individual’s personal characteristics and the environmental influences.

This finding is further supported by Faber and O’Guinn (1992) who affirm that compulsive buying behaviors mainly arise from five main personality dimensions. These dimensions include agreeableness, extraversion, neuroticism, conscientiousness, and imagination.

The research study showed that all the respondents characterized by compulsive buying behavior have a common factor that motivates them to engage in such behavior. One of the most common factors entails avoidance. Therefore, consumers develop such behavior in an effort to avoid situations that are unpleasant to the customers.

Some consumers engage in such practices in an effort to leave a potentially provoking situation. Williams (2009) emphasizes that ‘avoidance can also be a more subtle and include things like quickly leaving anxiety-provoking situations as soon as any anxiety is noticed’ (p.124). Therefore, some consumers engage in compulsive buying in an effort to avoid certain situations depending on their feeling. From the findings, avoidance can be categorized into three main levels, which include

- Active avoidance; this form avoidance is aimed at distracting an individual’s compulsive buying behavior. This form of avoidance mainly targets avoiding unwanted emotions, memories, failures, and experiences that stimulate the development of compulsive buying behavior.

- Compensate for control; this form of avoidance is aimed at limiting the development of compulsive purchasing behavior due to pressure from different sources such as family and workplace amongst other sources of pressure.

- Avoidance in an effort to cope with life problems

Conclusion

Understanding the consumer buying behavior comprises a vital element in organization’s marketing activities. First, understanding the buying behavior provides organizational managers insight on the most effective strategy to adopt in order to influence the consumers’ purchase decision-making process.

Organization’s marketing managers should appreciate the existence of differences with reference to consumer buying behavior. The study shows the consumers’ buying behavior is a factor of the consumers’ personality and the influence of the external pressures. This phenomenon is well illustrated by the compulsive buying behavior.

The behavior entails a compelling need to purchase a product or service in an effort to satisfy a particular need.

The compulsive buying behavior may have a negative impact on the consumer’s purchasing power because the consumer engages in excessive purchase of commodities aimed at addressing psychological needs such as anxieties and avoidance of negative emotions such as humiliation and ignorance.

Therefore, one can argue that the compulsive buying behavior is motivated by the need to entrench an individual’s social status or class.

Compulsive buying behavior stimulates consumers to make purchases without considering the consequences of their behavior including post-purchase guilt. Past research conducted in Westerns nations’ settings like Germany, Canada, and the US considers it as a personality disorder.

On the contrary, this research adopted a different paradigm. It studied the issue as a lifestyle problem. This goal has been achieved by comparison of purchasing behavior across consumers from Eastern countries such as China.

The study underscores the existence of similarity with reference to the factors stimulating development of compulsive buying behavior across consumers characterized by varied cultural and social characteristics. One of the reasons for the existence of compulsive buying behavior entails avoidance.

Consumers characterized by such practices are motivated by the need to avoid an unfavorable occurrence in their consumption patterns.

In summary, understanding the compulsive buying behavior is a fundamental element in improving an organization’s capacity to generate sales by exploiting the compulsive buying behavior.

For example, organizations should consider integrating effective marketing strategies that influence the development of compulsive buying behavior amongst consumers. One of the fundamental aspects that marketers should take into consideration entails the consumers’ personality.

References

Black, D. (2001). Compulsive Buying Disorder: Definition, Assessment, Epidemiology and Clinical Management. CNS Drugs, 15(1), 17–27.835

Dittmar, H., Long, K., &Bond, R. (2007). When a better self is only a button click away: associations between materialistic values, emotional and identity-related buying motives, and compulsive buying tendency online. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26(3), 334-361.

Edwards, A. (1993). Development of a New Scale for Measuring Compulsive Buying Behavior. Financial Counseling and Planning, 4(2), 67-85.

Eren, S., Eroglu, F., & Hacioglu, G. (2012). Compulsive Buying Tendencies through Materialistic and Hedonic Values among College Students in Turkey. Social and Behavioral Sciences, 58 (1), 1370 –1377.

Faber, J., & O’Guinn, C. (1992). A Clinical Screener for Compulsive Buying. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 459–469.

Faber, R., & O’Guinn, C. (1989). Compulsive Buying: A Phenomenon logical Exploration. Journal of Consumer Research, 16(2), 147–157.

Finlay, L. (2006). Rigor, Ethical Integrity or Artistry” Reflexively Reviewing Criteria For Evaluating Qualitative Research. British Journal of occupational Therapy, 69(7), 319-326.

Freshwater, D., Sherwood, G., & Drury, V. (2006). International research collaboration: Issues, benefits and challenges of the global network. Journal of Research in marketing, 11(4), 295-303.

Goodstein, L., & Lanyon, R. (2009). Application of Personality Assessment to the Work Place. Journal of Business and Psychology, 13(3), 291-313.

Grant, R., Clarke, R., & Kyriazis, E. (2013). Modeling Real-Time Online Information: A New Research Approach for Complex Consumer Behavior. Journal of Marketing Management, 29 (8), 950-972.

Kihlstrom, J., Beer, S., & Klein, B. (2002). Self and Identity as Memory. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Koran, L., Faber, R., Aboujaoude, E., Large, M., & Serpe, R. (2006). Estimated Prevalence of Compulsive Buying Behavior in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry, 16(3), 1806-1812.

Kukar, M., Ridgway, N., & Monroe, K. (2009). The Relationships Between Consumers’ Tendencies To Buy Compulsively and their Motivations to Shop and Buy on the Internet. Journal of Retailing, 85(3), 298-307.

Li, S., Unger, A., Bi, C. (2014). Different Facets of Compulsive Buying Among Chinese Students. Journal of Behavioral Addiction, 3(4), 238-245.

Maraz, A., Eisinger, A., Hende, B., Urbán, R., Paksi, B., Kun, B., Demetrovics, Z. (2014). Measuring compulsive buying behavior: Psychometric validity of three different scales and prevalence in the general population and in shopping centers. Psychiatry Research, 225 (2), 326-34.

Mueller, A., Mitchell, J., Claes, L., Faber, R., Fischer, J., & De Zwaan, M. (2011). Does Compulsive Buying Differ Between Male and Female Students? Personality and Individual Differences, 50(3), 1309-1312.

Neuner, M., Raab, G., & Reisch L. (2005). Compulsive Buying in Maturing Consumer Societies: An Empirical Re-Inquiry. Journal of Economic Psychology, 26(4), 509–522.

Otero-López, J., & Pol, E. (2013). Compulsive Buying and the Five-Factor Model of Personality: A Facet Analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 55 (1), 585-590.

Pachauri, M. (2001). Consumer Behavior: A Literature Review. The Marketing Review, 2(1), 319-355.

Saunders, M., Thornhill, A., & Lewis, P. (2009). Research Methods for Business Students. New York, NY: Prentice Hall.

Scott, S. (2011). Research Methodology: Sampling Techniques. Journal of Scientific Research, 2(1), 87-92.

Strang, K. (2015). The Palgrave handbook of research design in business and management. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Stricker, G., Widiger, T., & Weiner, I. (2003). Handbook of Psychology: Clinical Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

Williams, C. (2009). Overcoming anxiety, stress, and panic; a five areas approach. New York, NY: CRC Press.