A Brief History

In the history of the academic development of nursing theories, there are a variety of iconic figures who have made significant contributions to the evolution of the discipline: one of them is Betty Neuman. According to her official biography, Neuman was born in the American state of Ohio in 1924 (NT, 2021). Over the next thirty years, Neuman pursued her education and received a registered nurse degree from the People’s Hospital School of Nursing in Akron (1947), a bachelor’s degree in scientific nursing from the University of California (1957), and a master’s degree in mental health from the same university (1966). A little later, Neuman added a doctorate in clinical psychology to the degrees she had already received, making Betty Neuman a highly educated and credentialed professional. Neuman combined her work as a nurse with her master’s degree as well as teaching at UCLA. During her work practice, Neuman developed her own comprehensive system aimed at protecting psychological well-being and was able to produce her first book in which she laid out the foundation of her ideas by 1982 (Neuman, 1982). The central idea of this book was to strive to provide holistic care for the patient, which included consideration of all possible factors. The book has subsequently been reprinted several times, but the critical core of Neuman’s theory has remained unchanged.

Structure of the Theory

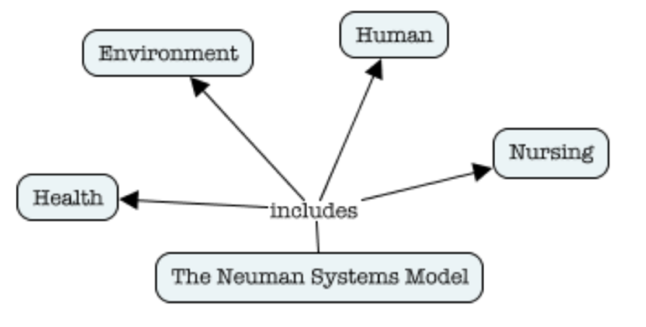

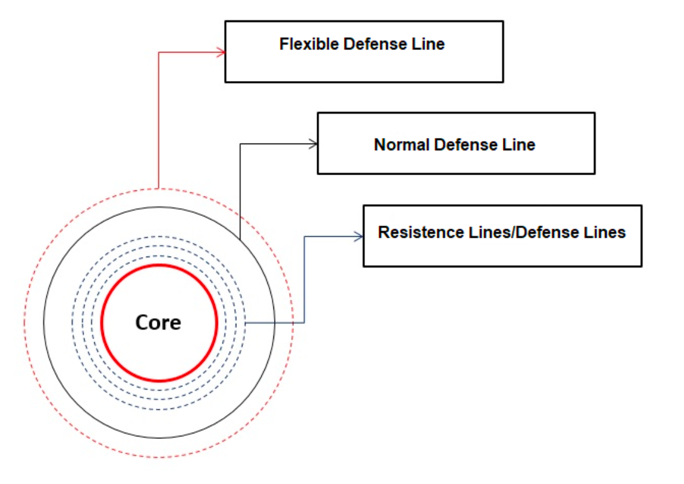

Neuman saw the basis for the formation of her theory as a desire to maximize the well-being of the population, including patients and their family members. Neuman’s nursing theory, also called The Neuman Systems Model, is to view patient health as a holistic system, not just a specific injury or pathology (Montano, 2021). The structure of this model includes four variables, namely the person proper, patient care, health, and environment (Figure 1) — the unique combination of these factors allows for the achievement of holistic patient care (Hannoodee & Dhamoon, 2021). Notably, in Neuman’s theory, the person as the primary resource is not necessarily represented directly by the sick person but can also be the family as a social unit. In examining this model, a diagram of three concentric rings, as shown in Figure 2, is often encountered. The rings identify the lines of protection of the central core, namely the patient’s physical and mental health. The flexible line, the outer layer, is the defense against stressors; if this line is broken, the resistance layer is activated. In Figure 2, the middle ring is the normal line, describing the normal state of the person, in which he appears healthy. So, in the case of external stimuli, the inner ring tries to stabilize the normal line, but if this layer is broken through as well, the person dies.

Thus, the structure of the Neuman system is described graphically and represents the protective barriers that are activated when exposed to external stressors. Consequently, this model views the human being as an open system capable of exchanging information and resources with the outside world. Lines of defense are designed to protect the core, which is a client system that includes the essential elements, as shown in Figure 1. Obviously, these schemes are metaphorical and do not exist as rings in real life, but they perfectly describe patient health as a dynamically evolving process capable of self-repair.

Linking Theory to the Components of Practice Change

Any change in nursing practice must be based first and foremost on scientifically proven facts and time-tested theories. In embodying the practice of early diagnosis of depression among 18-40-year-old patients, a key factor is to shift the focus from change per se to change that will promote sustained well-being among patients. Specifically, Betty Neuman viewed stress as one of the critical factors that can disrupt the balance of concentric rings in the context of patient health; in other words, Neuman focused on the problem of stress reduction for patients. It is this core, stress reduction, which is the crucial foundation for shaping the project. Patients’ depressive states are an extremely sensitive problem and can be exacerbated when exposed to stressful conditions. The classification of two causes of depression, namely exogenous and endogenous, is well known (Orsolini et al., 2020). Endogenous factors of depression should include those that are formed from within the body: as a rule, it refers to the dysfunction of the metabolic and hormonal systems. On the contrary, exogenous factors of depression are those stimuli that provoke depressive disorders from outside: it can be the loss of a loved one, a deeply emotional experience, or an abrupt change in the comfort of life, for example, as a result of war. In other words, a whole host of potentially dangerous threats exist in relation to depressed patients, and it is for this reason that special attention should be paid to this problem.

The practice is developed to make an early diagnosis of depression during primary care make it possible to assess the stressors potentially affecting the patient. Neuman’s model is then used as a working application that provides holistic patient oversight and allows for the identification of threats and risks. Specifically, Neuman recognizes that each patient has a unique situation, and it is not possible to treat the client as following or similar (Montano, 2021). Instead, Neuman’s model encourages a careful, caring, and involved examination of the patient’s history, ensuring integrity and comprehensiveness. For example, if a patient who complains of headaches comes in for an initial examination, the practice of the Neuman model, in this case, includes not only dealing with the symptomatic manifestation of the headaches but also exploring potential environmental factors, internal or external, that may have led to this condition. Detecting stressors that potentially affect the patient, whether they are cutbacks at work or conflicts in family relationships, plays a crucial role in the preventive diagnosis of pre-depressive disorders. Stressors disrupt the flexible line and destabilize the patient’s normal layer of health, and in the absence of the use of reactive measures, underlying stress has the potential to develop into complex depression (Norouzi et al., 2020). As a consequence, there is a need for widespread application of the Neuman model to any patient who fits the criteria of the project under development. However, it is critical to recognize that any work with the diagnosis of stressors potentially leading to depression and patient education must be done strictly after the patient’s primary complaint is resolved because otherwise, comprehensive care will prove to be disruptive to the patient’s health.

The classic components of nursing practice developed during the project include dealing with stress, being attentive to the patient’s history, and implementing comprehensive care; applying the Neuman model supports each of these components. In particular, one of the first tasks in early diagnosis is an engaged exploration of the client’s history — this can be accomplished through a series of standardized questions prompting the patient to talk about themselves. Guiding questions identify potential stressors that have a disruptive effect on the patient’s well-being (Dugdale, 2021). Including consideration of the patient’s history implements a component of holistic care because it involves examining the client’s connections and relationships to the environment, family, and institutional resources. Once stressors are found, the primary clinical care provider should conduct educational practices to teach the patient how to cope with stress and develop a resilient flexible line. It is necessary to educate the patient that systemic stressors can cause the development of prolonged depression, so preventive work to address stressors proves necessary (Norouzi et al., 2020). Such training need not necessarily be systemic and long-term, as there is no guarantee that the patient will return — for this reason, the transfer of experience should be optimized through guidelines and recommendations to reduce stressors. In this case, the clinical provider should not be a coach or mentor but should encourage the patient to mobilize their own resources to cope with stress, whether by implementing mindfulness practices or removing stressors from the patient’s life. Such sequential steps, using the Neuman model as a fulcrum, succeed in shaping the practice of early diagnosis and further management of depressive disorders among primary care patients.

References

de Albuquerque, R. N., & da Silva Borges, M. (2021). Suicidal behavior: An understanding from the perspective of Betty Neuman theory. Revista Baiana de Enfermagem, 35, 1-11.

Dugdale, D. C. (2021). Communicating with patients. MedlinePlus. Web.

Hannoodee, S., & Dhamoon, A. S. (2021). Nursing Neuman systems model. NIH. Web.

Montano, A. R. (2021). Neuman systems model with nurse-led interprofessional collaborative practice. Nursing Science Quarterly, 34(1), 45-53. Web.

Neuman, B. (1982). The Neuman systems model. Application to nursing education and practice. Appleton‑Century‑Crofts.

Norouzi, E., Gerber, M., Masrour, F. F., Vaezmosavi, M., Puehse, U., & Brand, S. (2020). Implementation of a mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program to reduce stress, anxiety, and depression and to improve psychological well-being among retired Iranian football players. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 47, 1-13. Web.

NT. (2021). Betty Neuman. Nursing Theory. Web.

Orsolini, L., Latini, R., Pompili, M., Serafini, G., Volpe, U., Vellante, F.,… & De Berardis, D. (2020). Understanding the complex of suicide in depression: From research to clinics.Psychiatry Investigation, 17(3), 1-10. Web.