Federal budget deficit occurs when the government expenditure exceeds the government income through revenue in a fiscal year. For instance, the last year the US federal deficit was $ 1.57 trillion, and this year, it is estimated to come to $1.267 trillion (Amadeo 2).

The problem with this deficit is that every year, it is added to the already existing Federal Debt which currently stands at over $ 14 trillion. Two thirds of this Federal Debt is the money owed by the federal government to the public, private companies and even foreign governments who bought treasury bills, notes and even bonds.

The remaining third is money owed by the federal government to itself in the form of government account securities usually from trust funds, thus, they are to be paid back after a certain period of time, when the baby boomers retire (Chantrill 8). There are several consequences that arise as a result of federal budget deficit which must be explored keenly to establish the dangers that lie ahead.

Every fiscal year, the budget is bound to go one way or another. There can be a deficit one year, and the following year, the state may enjoy a budget surplus. However, in the US federal budget, surplus has been elusive. For instance, between the years 1929 and 1969, the federal budget recorded a surplus only nine times, and it had never happened for three consecutive years at one time (Cashell 5).

First, the federal budget fails to distinguish between “operating” and “capital” expenditures. Operating expenditures are those incurred in running government and funding the services it provides; capital expenditures relate to purchases of long lived buildings and equipment, and include expenditures on infrastructure. The failure to distinguish these types of expenditures is at odds with accepted accounting practice, and is at odds with the accounting practices adopted by corporate America.

It amounts to claiming that expenditures on roads and buildings are equivalent to consumption, and that these assets are fully used up in the year they are purchased. The result is to overstate spending, and give government an air of profligacy. If capital expenditures were appropriately capitalized, both government expenditures and the deficit would be lower (Palley 4).

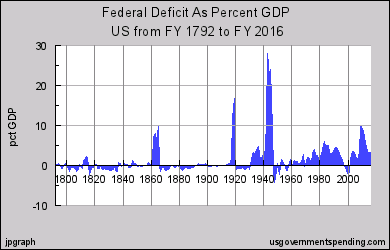

Figure 1 and table 1 below show the budget deficit over the years. The table 1 elaborates the federal deficits in figures between the year 2000 and the projected deficit up to the year 2016.

Figure 1

Source: usgovernmentspending .com

Table 1

Source: usgovernmentspending .com

From a position of near budget balance in 1970, the budget went into deficit. In part because of an economic contraction beginning in late 1973 and ending in early1975, the surplus fell to -4.2% (in other words, a deficit equal to 4.2%) of GDP in1976. Another economic downturn began in mid-1981 and ended in late 1982 contributing to another drop in the surplus, to -6% of GDP in 1983. Since then, with a brief reversal attributable to an economic contraction in 1990 and 1991, the surplus

increased steadily until 2000. In FY2001, the surplus fell from 2.4% of GDP the previous year to 1.3% of GDP. In 2002, there was a budget deficit (a negative surplus) of 1.5% of GDP and by FY2004 it had reached 3.6% of GDP. While the budget has clearly been influenced by changing economic conditions there nevertheless appeared to be a tendency towards smaller and smaller surpluses (at the time they were characterized as increasing deficits, which is the same thing) between1970 and 1983. Through 2000, that trend had been reversed, but over each of the next four years the surplus declined (Cashell 5).

Deficit spending increases the debt of the country every year. The argument put forward it is that deficit spending would help to increase the economic growth which is partially true in the short term, especially in times of recession like it has been experienced in the last three years . However the final result of deficit spending is never pleasant as the economy experiences a lot of damage due to the interest rates that have to be paid in the long run.

This interest is added to the debt every year, actually about 5% of the budget every year goes to interest payments. For instance, in 2009, the interest accrued amounted to $383 billion which had actually reduced from $451 billion only due to lower interest rates at the time in the fiscal year 2008. Sadly, it is predicted that the figure will be four times larger in the year 2020 which is estimated to $840 billion (Amadeo 3).

When this happens, the creditors will start doubting the ability of the government to repay the loans and, hence, will look at it as a great risk. As a result, they will be justified to ask for greater returns in terms of increased interest rates which will cost the government even more money and slow down the economy.

Other measures to counter the problem have proved futile due to various economic back lashes. For example, an attempt by the government to let the value of the dollar dip so as to lower the amount of debt payable backfires since investors become less willing to purchase the treasury bonds at the same time (Cashell 6).

By borrowing from the social security fund, the government shoots itself in the foot. This is in the view that paying the debt would be an uphill task when the time finally comes since the government is forced to borrow from the same kitty every year.

The consequences of this are that borrowing from the social security would be stopped and considered that this accounts for more than a third of the deficit which would be great to blow to the government. Evidently, this would slow down the very economy that gets a boost from deficit spending (Cashell 7).

Once, Thomas Jefferson said that “I place economy among the first and most important virtues, and public debt as the greatest of dangers. To preserve our independence, we must not let our rulers load us with perpetual debt” (Forbes.com, 6). What he wanted to illustrate is the fact that running a balanced budget had more advantages than running a deficit spending.

Several factors support this saying since balance budgeting is within the reach of federal government. In the year 1998, the budget office of the US congressional forecasted “shows the federal budget to be in effective balance, with a projected deficit of just $5 billion this year—a trivial percentage of an estimated $8.5 trillion gross domestic product” (Forbes.com 5). What followed that is that the government was able to balance the budget without causing any negative complication.

One measure economists use to assess fiscal policy is the structural, or standardized-employment, budget. This measure estimates, at a given time, what outlays, receipts, and the surplus or deficit would be

if the economy were at full employment.5 It is a way of separating changes in the budget totals that are due to changes in overall economic conditions from those changes that are the result of deliberate changes in tax and spending policy. Changes in the standardized-employment surplus reflect changes in policy and are not affected by variations in underlying economic conditions.

For example, if the economy is less than fully employed, then the standardized measure of outlays is less than actual outlays, standardized receipts are higher than actual receipts, and the standardized budget deficit would be smaller than the actual deficit. Economists track the standardized-employment surplus as a percentage of potential GDP to assess if fiscal policy is simulative or contradicting. As the economy grows, outlays and receipts tend to rise as well.

Comparing the budget to GDP filters out changes due to variations in the overall size of the economy. Potential GDP is an estimate of what the total value of production of goods and services would be if labor and capital resources were fully employed. Using potential GDP as a base for comparison avoids the problem of cyclical factors masking changes in fiscal policy. A decrease in the standardized budget deficit relative to

potential GDP would be considered indicative of a contractionary fiscal policy. Similarly, an increase in the standardized budget deficit as a percentage of potential GDP would be indicative of a simulative fiscal policy (Cashell 8).

Works Cited

Amadeo, Kimberly. “How the U.S. Federal Debt and Deficit Differ and How They Affect Each Other,” 2011. Web.

Cashell, Brian W. “The Economics of the Federal Budget Deficit.” CRS Report for Congress Journal, Vol 2, (2005) P12-13.

Chantrill, Christopher. “US Government Spending History from 1900 US”, 2011. Web.

Forbes. “Thoughts on the Business of Life”, 2011. Web.

Palley, Thomas. “The Sorry Politics of the Balanced Budget Amendment,” Challenge Journal, 40, May/June 1997, 5 – 13.