Introduction

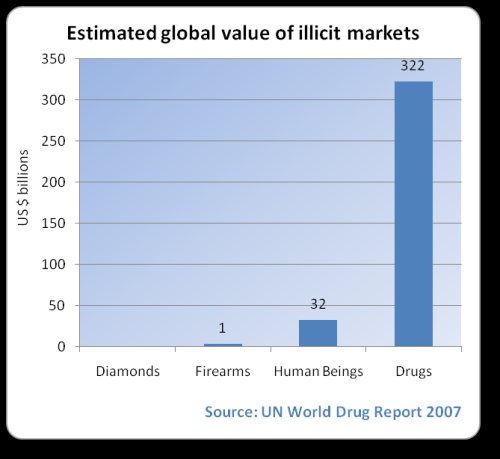

This is one of the most thriving trades in the world markets owing to the fact that, although majority of nations have criminalized drug trafficking, due to effects of the economic crisis that affected most nations, the trade provided and has been providing an alternative way of covering the revenue deficits that occurred ed in most nation’s budgets. For example, research by the United Nations on the impacts of drug trafficking on world economies showed that most countries benefited from the $325 billion, which the drug syndicate generated.

Such benefits were either direct; out of drug selling, or indirect; out of criminal proceedings (Syal, p.1). In addition, due to the looming poverty levels in many global societies, and the weaknesses that exist in many governments’ legislation that prohibit the trade, majority of individuals venture into the trade with prospects of upgrading their economic statuses due to many incentives associated with the sale of il to legal drugs (Darryl, p.1).

Therefore, this shows how hard it is for most nations to completely abolish the practice, owing to the many benefits such nations receive from the trade. On the other hand, it is important to note that, although some of such drugs are important in medicine, the majority of them have many associated societal problems, which are either political or economic.

For example, as research by the Nation Members of Club De Madrid (p.1) shows, there is a great correlation between illegal drug trafficking and terrorism; one of the most dangerous world crimes

Illegal Drug Trafficking

Primarily, illegal drug trafficking encompasses all activities ranging from the time individuals venture into the practice of planting illegal drugs, to the distribution and sale of such drugs in black markets. Majority of nations have illegalized the trade. Hence, anyone caught transacting or using the drugs must face a tough prison sentence or in some Asian countries, a death sentence.

Although this is the case, it is important to note that, in some countries, governments give specific individuals licenses to conduct such a trade, so long as they conduct their businesses under the set rules for such a trade. Majority of individuals who engage illegally in this trade use the same trade mechanisms used by individuals in underground markets. Depending on the type of drug cartel, different individuals must specialize in different processes, which make up the trade.

Also, depending on the level of an individual in the business, the size of drug organizations they own vary ranging from the simple street sellers to the well organized multinational organizations well known globally (United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, pp.3-8).

It is important to note that, gains from illegal drug deals, are not only enjoyed by single individuals or organizations, but also many governments enjoy the many proceeds from the trade. The United Nation’s research on the importance of illegal drug cartels to governments in 2003 showed that the majority of nations enjoyed the $321.6 billion, which the sale of such illegal drugs generated.

Further, the same report showed that such drug proceeds contributed thirty-six trillion to the global Growth Domestic Product (GDP) hence, showing the importance of the trade to world economies; preceding its negative impacts on the society (Pollard, p. 1).

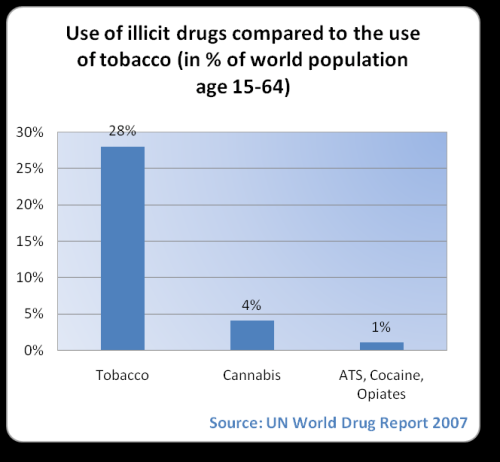

Considering this and the fact the number of consumers of these drugs keeps on increasing as poverty levels increase, curbing this form of trade and the use of most of these drugs is one of the hardest tasks that most governments have failed to achieve hence, the current state of the trade globally.

Causes of Increased Illegal Drug Trafficking

Illegal drug trafficking is not a new concept to any global nation, but rather it is a practice that has existed since time memorial, although in the past their manufacture and sale was a little bit different, as compared to the present situation of well developed and extended drug cartels and dealings.

That is, prior to the illegalisation of the sale of such drugs, previously countries could conduct the trade among themselves freely, although in the awakening of the 18th century countries such as China and Britain illegalized the trade hence, giving birth to the mafia groups, for example, the famous Chicago’s Al Capone cartel.

As more countries joined in the war more mafia and organized gang drug syndicates sprung up, leading to the current widespread groups that engage in the trade (American Law and Legal Information Centre, p.1)

One primary causative agent of the ever-increasing illegal drugs trade is the nature of economic incentives associated with the drugs. For example, the United Nations report on the effect of the sale of drugs on the Bolivia economy revealed that, as compared to revenue gains from other sectors of its economy, the sale of cocaine was one of the primary contributors of increased Bolivia’s revenue collection.

The report further added that earnings from this trade are the primary contributors to the developments of most poor societies, which produce the drugs. This is the case primarily because revenues from the sale of illegal drugs act as a main economic booster to the social mobility and gain of power in societies.

In addition, it is important to note that, as compared to other agricultural products, earnings from drugs in most cases act as better economic multipliers hence, a major contributor to regional economies (United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, pp. 5-6 and United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, pp. 169-171). On the other hand, this trade mostly takes place in underground or black markets where government law-enforcing agents cannot easily access and apprehend this crime’s perpetrators.

That is, with many legal sanctions in almost all countries, the majority of drug dealers conduct their trade in areas they are very sure there is enough protection from the long arm of the law.

Although the majority of the “big” dealers are rich individuals, the majority of the planters and processers of these drugs are mere peasant farmers who are struggling to free themselves from bonds of poverty. It is important to note that, majority of drugs originate from less developed nations, and their consumption is more in more developed nations (Paez, p.1).

Although most individuals associate technological innovations with profitable developments in the world, to some extent, such technologies have contributed negatively to the social well being of global communities. That is, the majority of drug lords use the most current and exotic technologies in accessing their markets, without having to travel to such markets.

This like a situation is common in India, whereby traffickers conduct their deals via the internet hence, leaving the delivery role to the national couriers and other transfer services. The main reason behind the success of this form of trade transfer is because; such services are government coordinated hence, in most times it is very hard for law-enforcing agents to apprehend such dealers.

Such technologies include the most recent innovation of money transfer electronically hence, regardless of the drug dealers’ position, they can make online deals, and suppliers deliver their goods at their convenience and with little exposure (Majumdar and Tharakan, p.1).

The global economic crisis also has contributed to the increasing rates of drug trafficking. That is, majority of individuals involved in this trade have taken advantage of the present global economic situation to expand their transactions, owing to the economic deficits, which the economic recess caused in many nations’ revenue collections.

With globalization, the world trade patterns have undergone transformations, a fact that has contributed to the expansion of financial systems and development of better and appropriate market situations. Such developments have provided fertile grounds for the development of this illegal trade, as the trade adheres to the changing micro-economic conditions.

Also, such economic developments have afforded illegal drug traders an opportunity of offering incentives for their sales to other individuals who might be interested in the trade. Hence, owing to the promising nature of revenues from this trade, the majority of businesspersons have ventured into the trade (United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, pp. 3-4).

The fourth primary factor, which has contributed to the increase of the trade are the currently existing many porous borders. Although most world governments, for example, the U.S. government have strict control measures in their borders and even some use their militaries to apprehend drug traffickers, some border protection policies are weak hence, so far most of them have achieved little, as corruption looms in among law enforcing agents.

In addition, a majority of nations have very weak border laws, factors promoted by the political turmoil many counties are suffering hence, the ineffectiveness of such policies to contain the situation in most countries for example, in countries such as Peru, Afghanistan, and Colombia (United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, pp. 4-7).

Lack of enough data to many governments is another main contributor to the increased rate of illegal drug traffic. The fact that most individuals; more so users are not willing to give narcotic control agencies the required data, has been one of the greatest impediment to many governments, as far as control of the production, use, and sale of the illicit drugs is concerned.

Majority of nations, for example, Canada, and some Eastern European countries have felt the impact of the sale of such illicit drugs, however, to obtain accurate data on the consumption, sale, and use of such drugs has been one of the hardest problems to such governments. This is because; illegal trade is an underground occurrence; hence, very hard to know the real users and suppliers.

Implications of Such Rapid Increases

Although some illicit drugs may contribute to the General Development Product of countries while some of them have some medicinal significance, it is important to note that, the negative effects of such drugs are many not only to an individual but also to the entire society. This means that the rapid increase of production, sale, and use of most illegal drugs has adverse effects on the general social and political systems of nations involved in the business.

From research, there is a close correlation between illegal trafficking and the rate of global crime, more so terrorism. Cocaine is one of the most trafficked drugs, has the highest rate of criminal offenses, as individuals endeavor to utilize all means at their disposal to ensure they achieve their sale targets.

In addition to the increase in the global rate of crime, because the majority of peasant farmers are the lowest in rank, as far as the crime is concerned, likelihoods of most of then falling victims of the traffickers are high, as the marketing of such drugs uses no lawfully accepted protocols. Closely related to the rate of crime is the government expenditure in taming the vice in society.

With the rapid increase of this vice in the society, likelihoods of government expenditures increasing are high, due to the increase of this crime’s perpetrators in prisons. Such extra expenditures is a wastage of resources, which governments can use in other development sectors of their nation’s economies (Office of National Drug Control Policy, p. 16)

On the other hand, economically, the majority of activities of many drug cartels may sometimes have adverse effects on the legal economy. This case occurs because excessive gains from drug trafficking can cause an overvalued exchange amounts.

In addition to the overvalued exchange rate, such rapid increases cause this trade’s revenues can cause an increase in crime tax; a tax that is primarily enjoyed by the middle person in the trade, rather than the producers, who are peasant farmers. Hence, to some extent, the trade may contribute to the increased rate of poverty in societies (United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, p. 5).

Drug trafficking also has related to complex medical problems. That is, the primary mode of consumption used by most drug users is injections whereby, in most scenarios, majority of individuals share needles with little consideration on likelihoods of contracting complicated health problems, for example, HIV and AIDS.

Such cases have occurred in India and Thailand, where the World Health Organisation has reported the biggest number of HIV transmission as a result of increasing illegal drug use. Considering this, likelihoods of increase in infections are high; hence, the need for governments to tame the vice (Avert, p.).

Conclusion

In conclusion, although governments are putting up strict measures aimed at controlling the flow of illegal drugs, such measures have achieved little as far as control of the production, sale, and distribution of illegal drugs is concerned. This is because earnings from the sale of drugs such as cocaine, heroin, and marijuana, in most nations exceed what such countries earn from other sectors hence, making some countries to promote the trade, as others endeavor to eliminate the sale and use of such illegal drugs.

Also, failure of most government’s efforts to eliminate such drugs from their markets has led to the current problems faced by many nations, which to a larger extent have disrupted most economic, social, and political systems of many countries.

It is important to note that, failure of many governments’ initiatives to eliminate such drugs from its streets is primarily because, with globalization and many technological innovations, the world trade systems have undergone a great transformation hence, providing an easy getaway of many drug lords.

Therefore, considering the current state of drug trafficking, it is important for all governments to combine efforts hence, ensure they work with some form of unison, it being the only way of taming the vice from global societies. To achieve such endeavors, it is important for all governments to take into consideration all factors, whether political, social, or economic, whose integration will help in the formulation of workable solutions.

Works Cited

American Law and Legal Information Centre. Organised crime – American mafia. Net Industries. 2010. Web.

Avert. Injection drugs, drug users, and HIV & AIDS. Avert, 2010. Web.

Club De Madrid. Causes of terrorism: links between terrorism and drug trafficking: a case Of Narco-Terrorism. International Summit on Democracy, Terrorism and Security, 2005. Web.

Daryl, Detsg. Poverty and drug Abuse. Police Link. 2008. Web.

Majumdar, Bappa, and Tharakan, Tony. Illegal drug trade via internet on the rise in India-report. Thomson Reuters. 2010. Web.

Office of National Drug Control Policy. Drug related crime. ONDCP, 2008. Web.

Paez, Angel. Poverty provides growing number of “drug mules.” Inter Press Service: IPS. 2010. Web.

Pollard, Niklas. UN report puts world’s illicit drug trade at estimated $321 b. Boston, 2005. Web.

Shah, Anup. Illicit Drugs. Global Issues, 2008. Web.

Syal, Rajeev. Drug money saved global banks in economic crisis, claims a UN advisor. Pakalert Press, 2009. Web.

United Nations Research Institute for Social Development. Illicit drugs: social impacts and policy responses. UNRISD, 1994. Web.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World drug report. UNODC. 2007. Web.