Maori is the name of the people who historically inhabited New Zealand and are of Polynesian origin; they arrived there about a thousand years ago. Their culture is rich and comprises whakairo (carving), raranga (plaiting), kapa haka (performing), whaikōrero (oratory), and tā moko (tattooing). These arts record Māori beliefs and whakapapa, that is, genealogy. The Māori language is called Te Reo Māori, abbreviated to Te Reo. Many Māori are making efforts to preserve their traditional culture, and in recent years, Māori language teaching has been introduced in some schools.

The word Māori stands for ordinary or natural, which is how Māori mythology refers to mortal human beings as opposed to deities and spirits. There is a Māori legend about how they came to New Zealand in seven canoes from their ancestral homeland of Hawaiki. Modern research shows that the then-uninhabited New Zealand was settled by Polynesians around 1280 AD (Kleiner, 2016). By that time, all present-day human settlements were already inhabited. The ancestral home of the Māori and all Polynesians is the island of Taiwan near mainland China. People came to New Zealand directly from the islands of East Polynesia. Today Māori are actively involved in contemporary life and contribute significantly to the cultural development of New Zealand. Among them, one can find not only simple toilers but also talented engineers, designers, inventors, athletes, and politicians.

One of the critical ideas of Māori philosophy is the unity of man and nature. Māori explain it this way — every creation has a particle of life force (mauri). Due to Mauri, everything that exists in the world is interconnected. Since every part depends on everything else, neglecting to care for the world would be detrimental to the individual. Māori culture and religion in its classic form require the observance of many rituals designed to minimize the potential harm that can be done to all of nature in general and to humans in particular (Kleiner, 2016). The Māori explanation of why it is necessary not to harm wildlife is fascinating. They think that for every action, whether hunting an animal or cutting down a tree, a good reason is needed, and it is necessary to ask the gods’ permission by special ritual.

Visual Māori art objects have one characteristic feature, which is the unity of form and function. That is to say, the items created were of not only aesthetic but also practical value. In the creation of objects were used mainly natural materials such as wood, linen, and stone. However, European colonization changed the nature of art and its functions. Through their art, the Māori began to protest against change. This culminated in the 1984 Te Māori exhibition, which was shown to the New York City public at the Museum of Art (Kleiner, 2016). It helped to make many people aware of the talent of Māori artists.

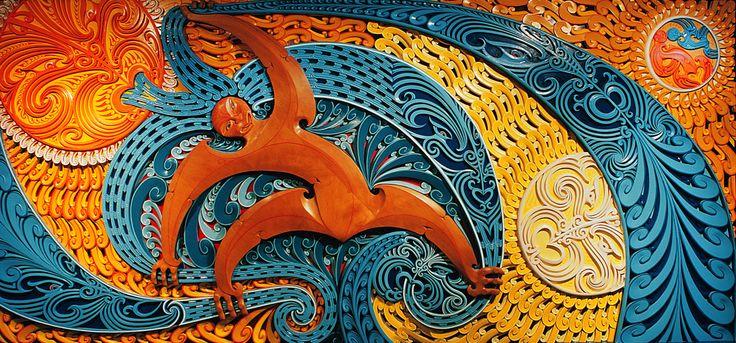

Myths of the indigenous peoples of Oceania often become the subjects of murals, which is an example of cultural renewal. A school of New Zealand artists inspired by Māori heritage, for example, is developing. Wood carving is a traditional craft that Aboriginal people have practiced for many years (Kleiner, 2016). One of the most famous murals depicts events from the Māori creation myth. The artist Cliff Whiting depicts the god of the winds struggling to control the children of the four winds (Figure 1). The winds are represented in the form of blue spiral shapes. In the fresco the gods of Māori culture can be seen — Ra, Marama, Ranginui and Papatuanuku (Figure 1). The mural’s author supports the idea that Māori culture must be saved and sustained. He believed that not only continuity in the arts is necessary, but also the education of young people in the spirit of indigenous peoples of Oceania values.

The Māori people have many beautiful legends, some of which can still be heard today as told by Māori oral storytellers. One of the main themes of the myths has to do with the sea and fishing. It was one of the main occupations of the Māori, who many years ago learned to sail on the open sea in special canoes called Waka (New Zealand Tourism Guide, 2022). One legend tells how the god Maui went fishing on the North Island (New Zealand Tourism Guide, 2022). This story describes the creation of three islands, North Island, Waipounamu, and Kaikōura.

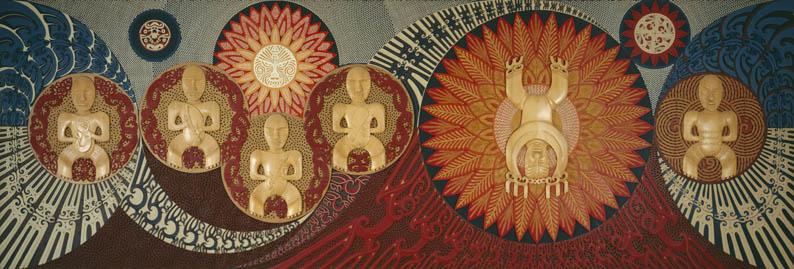

However, according to another myth, the universe began as nothingness from which darkness arose. Rangi and Papa are two primordial figures who emerged from this darkness. The six sons of Rangi and Papa later populated the world with all kinds of creatures and became gods (Grainger, 2022). Cliff Whiting decided to capture this story in one of his sculptures (Figure 2). It depicts these six gods trying to divide Rangi and Papa, as the legend implies. (Figure 2). Cliff Whiting’s attention to mythological subjects stems from his desire to remind the Māori people of their origins and their unity. In order to keep the audience interested in the work, the artist chose to use modern aesthetic techniques.

Māori poetry was sung or chanted, and its key difference from prose was that it was based on musical rhythms. In this kind of poetry, rhyme does not play a significant role. It is characterized by the repetition of keywords and the use of synonyms. It is accompanied by the presence of atypical grammatical constructions, which are not usually found in prose (Cowan, 1930). Contemporary poets of this trend include Hone Tūwhare, Jacquie Sturm, and Robert Sullivan. Māori poetry has many references to religious and mythological subjects. It is interesting to note that even Old-World poets found inspiration in the works of primitive people. They were struck by the way the Mari authors described the beauty of wildlife (Cowan, 1930). This is not surprising since the Aborigines have always lived in union with nature, and therefore, they learned how to skillfully tell stories about its greatness.

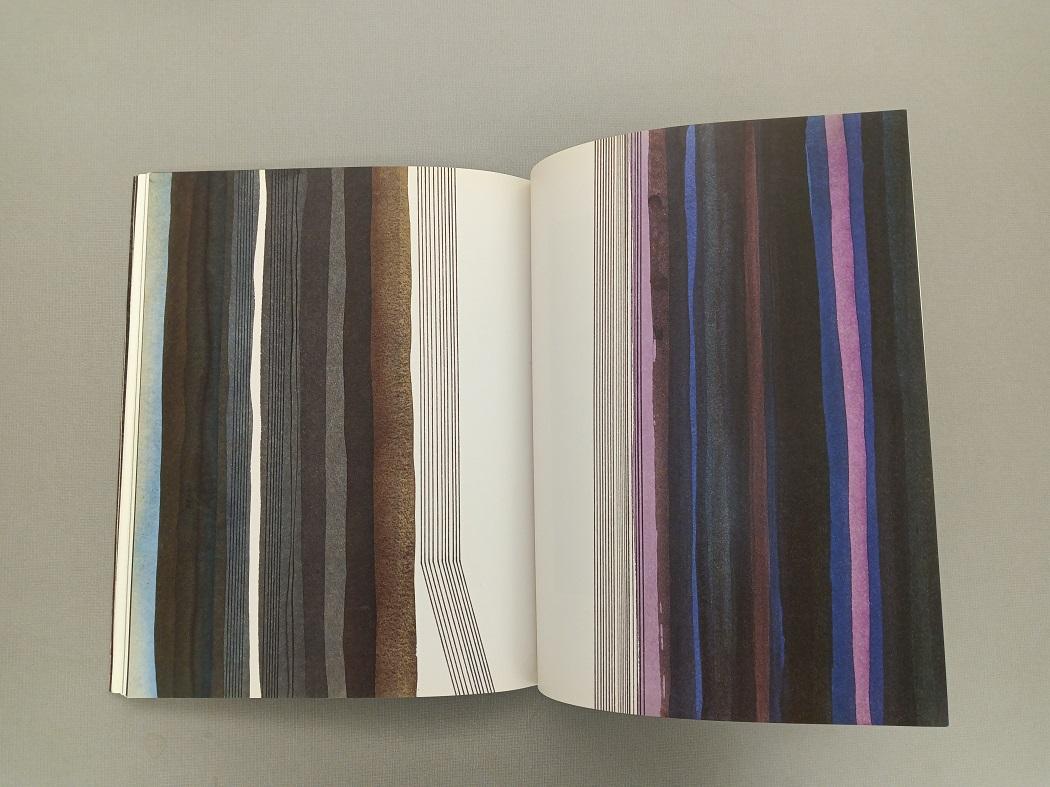

Hone Tuwhare was the first indigenous New Zealand poet to be translated into English. He was the recipient of several prestigious literary awards and was a strong advocate for the recognition of Māori culture. Hone Tuwhare and Ralph Hotere were two creators who were united by friendship and the struggle for human rights. Ralph Hotere used Tuware’s poems in several of his paintings. He also designed the covers for several volumes of the poet’s poems (Figure 3). Hotere is the title of a poem in which Hone Tuwhare reflected on the importance of art and the role of the artist. It is worth noting, however, that a close interaction between individual poets and sculptors or people engaged in woodcarving was uncommon.

In general, traditional Māori art is very much in harmony with modern realities. On the streets of New Zealand cities, one can see quite a few New Zealanders and tourists wearing traditional jewelry. The Māori tā moko motifs are becoming increasingly popular among people who want to get a tattoo. This tattoo culture is spreading to places where little is known about other aspects of Māori. Their traditions inspire fashion designers, and even such giants of the fashion industry as Jean Paul Gaultier use Māori style elements in his collections. Among contemporary Māori artists, it is worth noting Warren Pohatu. His drawings are, in a sense, a modern interpretation of traditional, although very close to real, authentic Māori art. This artist illustrated several books of Māori myths and legends — that is why his drawings often feature folkloric characters and well-known plots of traditional Maori myths.

References

Cowan, J. (1930). The Maori: Yesterday and today. Whitcombe and Tombs Limited.

Grainger, A. (2022). Polynesian creation myths: Ever wondered how Hawai’i was created? The Collector. Web.

Hotere, R. (1972). Drawings for Hone Tuwhare’s sapwood and milk[Painting]. Dunedin Public Art Gallery, New Zeeland.

Kleiner, F. S. (2016). Gardner’s art through the ages: A global history (15th ed.). Cengage.

New Zealand Tourism Guide. (2022). Māori stories and legends: The story of He Ika A Mau.

Whiting, C. (1984). Tawhiri-Matea (God of the Winds)[Mural]. Meteorological Service of New Zealand, Wellington, New Zeeland.

Whiting, C. (1969-1976).The separation of Rangi and Papa [Sculpture]. National Library of New Zealand, Wellington, New Zealand.