Introduction

Maori is a unique indigenous society that had a special developmental pattern, i.e. they moved from sedentism to hunting and again to sedentism. More importantly, now Maori constitute 15% of the population of New Zealand and they have managed to preserve their culture up to these days.

In this paper, I deal with the history of this indigenous society and focus on Maori people’s attempts to preserve their traditions and their culture. Understanding cultural peculiarities and being aware of the struggle of Maori will help better understand the importance of culture for a human society. It is necessary to note that Maori still cherish their traditions and are proud of their culture and history.

Background

According to archeological research, first settlements in New Zealand appeared as early as the twelfth century AD. This was the start of Maori society that has developed and changed several times since then. It is often believed that Western colonists used to bring a new order with them and change traditions and customs.

However, Maori society had undergone a number of changes before Western settlers came to New Zealand (Walter, R., Smith, I., Jacomb, C., 2006). It is important to note that roots of Maori society are found in East Polynesia (Walter, R. et al., 2006).

Therefore, it is not surprising that first settlers (who became Maori) had come to New Zealand with a certain societal order and culture. This peculiarity explains the shift from sedentism to hunting and fishing and to sedentism again. The newcomers came with their strategies which proved to be ineffective at certain period and it took some time to develop new strategies, e.g. to develop horticulture.

History

In 1300, settlers were involved in hunting, fishing as well as developing horticulture. As has been mentioned above, Maori society can be characterized by sedentism at early stages of their development (Walter, R. et al., 2006). However, Maori’s sedentism was a bit specific. Maori people lived in quite large settlements (villages), but these villages were mobile and were a part of a larger system. Walter, R. et al (2006) note that Maori’s sedentism was possible due to abundance of resources in certain regions.

It is necessary to note that Maori’s hunting and horticulture exhausted the environment. Thus, many species of game became extinct due to activities of Maori (Walter, R. et al., 2006). Thus, when a community exhausted some area, they simply moved to another place. It is necessary to note that different communities often had military conflicts.

The first contacts with Europeans started in the middle of the seventeenth century when first sailors and missionaries came to the islands (Pearce, G.L., 1968). The first contacts were friendly, so-to-speak. However, later there were a lot of conflicts. Europeans often killed Maoris and Maoris avenged and killed Europeans.

There were even cases of cannibalism (Pearce, G.L., 1968). In the nineteenth century, there were a number of military conflicts between Europeans and Maori people, e.g. the Anglo-Maori Wars which took place in the 1860s (Gump, J.O., 1997).

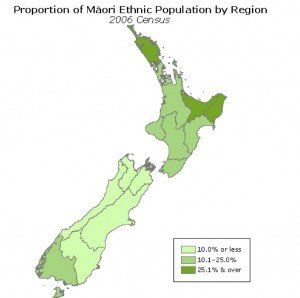

Those conflicts resulted in certain treaties which were often reconsidered. Basically, those wars could be regarded as the last attempts of Maori to defend their boundaries and preserve their autonomy (Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the difference between the boundaries of Maori lands in the 19th and 21st centuries). The first part of the twentieth century was the period when Maori lost most part of their land, and anthropologists even expressed concerns that Maori were almost extinct (Hanson, A., 1989).

Nonetheless, in the mid of the twentieth century, it became obvious that Maori were likely to preserve their culture and their language. In the 21st century, a variety of regulations aimed at development of Maori language and Maori culture exist in New Zealand (Hanson, A., 1989). It is necessary to note that Maori’s resistance to influences from outside played the crucial role in the development of their culture and language.

Political organization

As has been mentioned above, Maori settlements (villages) were mobile. These villages combined into communities which had chiefs (Walter, R. et al., 2006). Therefore, it is possible to state that in prehistoric period Maori had decentralized governance that was similar to the systems developed in Polynesian tribes and communities. This political structure has not dramatically changed throughout centuries. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the structure was predominantly the same and communities had their leaders.

Importantly, in the second part of the nineteenth century, British colonists started a large-scale acculturation and assimilation program (Gump, J.O., 1997). The governor in New Zealand George Grey believed that “rapid assimilation” will contribute to acculturation of the “savages” and it will put an end to the tension between indigenous people and European settlers (as cited in Gump, J.O., 1997, p. 25).

However, chiefs of Maori communities were against such acculturation, which led to a number of military conflicts and the movement called Maori King Movement, which was aimed to defend Maori people’s rights to own their land.

In the early twentieth century Maori people had certain governance bodies which addressed the parliament of New Zealand and even tried to address the British parliament, though it is necessary to add that these attempts were not successful and the government of New Zealand restricted political power of Maori communities (Gump, J.O., 1997). Maoris were still seen as aliens who had to be assimilated. Europeans still tried to ignore Maoris’ needs and demands.

One of the major reasons for Maoris’ failures can be decentralized social structure the Maori (Bourassa, S.C. & Strong, A.L., 2002). Maori still live in communities which are often hostile to each other. There is no unity among Maori communities. People of these communities still see each other as rivals, and fail to understand that together they can achieve more.

However, it is necessary to note that Maori people are represented in the parliament of New Zealand and this contributes to development of the movement aimed at development of Maori culture.

Subsistence/economic patterns

Maori used to rely on hunting, fishing and horticulture in prehistoric times. Abundance of natural resources made Maori prosper. However, when the resources became quite scarce, Maori had to move and find other ways to feed themselves. They were also involved in agriculture in later periods. In the eighteenth and especially nineteenth centuries, Maori started interacting with Europeans and they started relying on agriculture.

In the late nineteenth century and the first part of the twentieth century, Maori faced a variety of economic constraints. In the first place, acculturation and assimilation policies implemented by Europeans led to alienation of land. Maori were deprived of the right to own the land of their fathers.

Maori people often had to seek employment on Europeans’ farms, which contributed greatly to further economic difficulties for Maori. For instance, financial wellbeing of Maori was very moderate compared to that of Europeans. Maori used to fulfill low-paid jobs, which contributed to their financial problems.

Nonetheless, the rising interest to Maori culture led to attention to the land issues. In the second part of the twentieth century, Maori obtained an opportunity to restore some of the land that their ancestors used to own. Many communities and individuals were allowed to submit certain documents that could prove their rights on a particular site (Dixon, S., & Mare, D.C., 2007).

This positively affected Maoris’ wellbeing. They have become able to start small businesses. This contributed to prosperity of some communities. Maoris have become able to get a higher education, which led to new job opportunities.

Importantly, Maori were affected by financial crises of the 1980s-1990 most as they were involved in doing low-paid jobs. However, in the 2000s, financial well-being of working Maoris improved significantly (Dixon, S., & Mare, D.C., 2007). Now the difference between Europeans’ and Maoris’ incomes has decreased as Maori have started occupying well-paid jobs. Maori young people also obtain appropriate education which enables them to seek for better job opportunities.

Gender, marriage, family structure

It is necessary to note that Maori people can be regarded as one of the most unique indigenous nations as they managed to preserve their culture to a great extent. It is necessary to note that Maori society was predominantly patriarchal.

Chiefs were selected among men and men made the major decisions concerning warfare, leaving a particular area, etc. (Pearce, G.L., 1968). However, it is also necessary to note that women often played a significant role in the development of Maori society. Now Maori women are represented in the parliament of New Zealand.

It is also important to note that European settlers did not change family structure to a great extent. Christian values were quite similar to those of Maori people’s values. Interestingly, there are some peculiarities in Maori people’s attitude towards sexuality (Aspin, C., & Hutchings, J., 2007). Maoris could be characterized by certain sexual diversity as many other indigenous people. Contemporary Maoris also accept sexual diversity as they tend to focus on spiritual connection rather than gender.

Religion

Maoris’ religious beliefs are also quite specific. As any other indigenous people, Maoris had polytheistic religion. They worshiped many gods that were believed to control powers of nature. However, A. Hanson (1989) notes that Maori’s religion can also be regarded as monotheistic as there was a superior entity Io. Io was the embodiment of justice and the superior rule. Io was the power that created the universe.

Notably, Io was quite a specific cult as many Maori people were ignorant of this divine entity. Io cult was often for the chosen who were aware of the superior entity (Hanson, A., 1989). Maori believed that only highest priests and chiefs could be aware of the great god, as this knowledge was almost dangerous for ordinary Maori people.

Importantly, Io cult was quite similar to the religious beliefs brought by European settlers and missioners. Maori had quite similar values and similar understanding of the right and the wrong (Pearce, G.L., 1968). This was one of the reasons why Christianity spread among Maori people so fast (Hanson, A., 1989).

It is necessary to note that the cult of Io became a certain part of Christian beliefs of Maori people. Io was associated with Jehovah and Maori people were tolerant to the new religion. It is also necessary to note that Christian missionaries and settlers tried to eliminate ‘pagan’ beliefs and make Maoris accept Christianity which was a part of the acculturation strategy.

Therefore, it is possible to note that there were two major factors that contributed to spread of Christianity among Maori. On the one hand, Christians tried to convert the savages into their religion. On the other hand, Maoris accepted Christianity as a similar kind of faith (Pearce, G.L., 1968). Now most of Maoris are Christians who share Christian values, but still they cherish the beliefs of their ancestors.

The people today

As has been mentioned above, Maoris managed to preserve their culture to a great extent. They managed to preserve their language and their traditions. For instance, Io is still an important part of Maori cosmology even though most of Maori are Christians. Maori still have the same ideas concerning the right and the wrong. The superior entity is still seen as the embodiment of justice. Notably, these beliefs are intermingled with Christian principles, which makes Maori a unique society.

It is also important to state that Maori people have been struggling for their rights to remain Maori throughout centuries. The struggle is not over as Maori have to take a stand to advocate their rights (Dixon, S. & Mare, D.C., 2007).

The struggle for the land is not over as well. Maori still have to prove their rights to live on their land as predominantly European officials and entrepreneurs try to obtain this important resource. Apart from this, Maori also have to protect their culture and their language. The interest to indigenous people and their culture rose in the 1970s and this positively affected the development of Maori culture.

As far as economic well-being is concerned, it changed quite significantly compared to the situation in the twentieth century. Now income of working Maori has risen as they started occupying well-paid jobs. This became possible as higher education is now available to Maori. Of course, land policies and returning Maori land to them contributed greatly to economic empowerment of Maori people.

Nonetheless, Maori people still have to face a variety of challenges. Globalization contributes to assimilation of Maori. Now many Maori tend to abandon their home places and search for better life elsewhere.

This trend can be quite threatening as fewer people are preoccupied with preserving their indigenous culture and traditions. Besides, assimilation is quite an inevitable process as Maori are affected by traditions and ways of Europeans. These influences inevitably affect the way Maori culture is developing, so it becomes quite challenging to sustain a truly Maori culture.

Conclusion

It is necessary to note that Maori is one of the most unique indigenous societies which developed in a particular way and, irrespective of many hazards and the course of time, Maori managed to preserve their culture. This society has a history of a constant fight for their right to develop. At present, Maori people are achieving a lot of goals which were unavailable in previous centuries. Thus, contemporary Maoris are gaining economic independence, so-to-speak, and this contributes to their empowerment.

References

Aspin, C. & Hutchings, J. (2007). Reclaiming the Past to Inform the Future: Contemporary Views of Maori Sexuality. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 9(4): 415-427.

Bourassa, S.C. & Strong, A.L. (2002). Restitution of Land to New Zealand Maori: The Role of Social Structure. Pacific Affairs, 75(2): 227-260.

Dixon, S. & Mare, D.C. (2007). Understanding Changes in Maori Incomes and Income Inequality 1997-2003. Journal of Population Economics, 20(3): 571-598.

Gump, J.O. (1997). A Spirit of Resistance: Sioux, Xhosa, and Maori Responses to Western Dominance, 1840-1920. Pacific Historical Review, 66(1): 21-52.

Hanson, A. (1989). The Making of the Maori: Culture Invention and Its Logic. American Anthropologist, 91(4): 890-902.

Pearce, G.L. (1968). The Story of the Maori People. Auckland: Collins.

Walter, R., Smith, I. & Jacomb, C. (2006). Sedentism, Subsistence and Socio-Political Organization in Prehistoric New Zealand. World Archeology, 38(2): 274-290.