Introduction

A change from a centrally planned economy to a free-market economy took place in many developing countries worldwide. The transition process is marked by the liberalization of markets and economic stabilization (Yeager, 1999; Soto, 2000). In spite of similarities in a transition process, the performance of transition economies differs greatly because of the different economic conditions of the countries, their foreign policies, and economic integration into the world market.

The paper will discuss the impact of initial conditions on the performance of transition economies and the influence of different policies on these countries and their economic activities. The paper will compare European countries and Asian countries, concentrating on Poland and China.

Literature Review

The main layer of the literature concentrates on government policies and their impact on the transition stage (Dabrowski (2002; Redek & Susjan, 2005; Soto, 2000; Mukand & Rodrik, 2002). Legitimatization has mainly drawn on the prescriptions of neo-classical economics. Deregulation of domestic economic life, less state intervention in economic activities, and fewer obstacles to international trade. These are the main tenets of neo-liberal policy.

The other layer of literature compares transition economies of the Asian countries to European countries with an emphasis on government interventions and trade relations with developed countries. Woo et al. (1996) compare Asia and Europe during the transition stage. Special attention is paid to components of the reform programs and activities aimed to improve economic performance. Yeager (1999) and Campos & Coricelli 2000) concentrate on political economy and addresses the issues of neoclassical economic theory and the role of state institutions in the transition process.

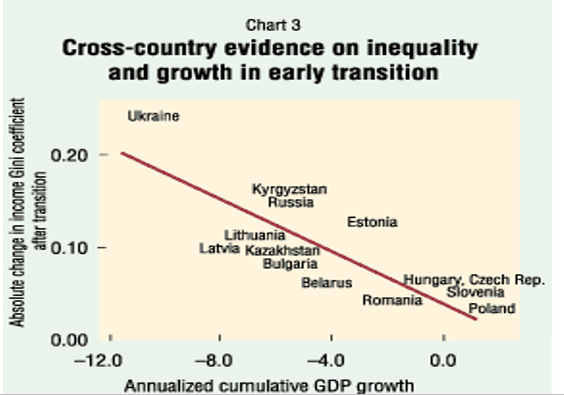

The author compares the results of different countries and analyses their impact on the global market. The same problems are dressed by Redek and Susjan (2005) in the article “The Impact of Institutions on Economic Growth.” Krueger and Ciolko (1998) underline that there is a close link between liberalization and performance. Thus, the researchers find that the government should not overstate the role of policy and reforms. De Melo et al. (1996) and de Melo et al. (1997) pay special attention to initial conditions of transition and the role of the market system before the change.

Definition of Transition Economies and their Role in Global Developments

Two processes have changed the political and economic map of the world in the 1990s and created new challenges and opportunities for enterprises in the periphery of the global economy. “Transition is well described as a period of “creative destruction,” of building up a market system and simultaneously destroying the legacies of at least half a century of locialism” (Campos & Coricelli 2000, p. 6). These are the dissolving of planned economies in Eastern Europe and Asia, the forceful promotion of structural adjustment programs in the South. Both these processes are essentially political.

However, politics usually has an economic side, and in these cases, economic theories have come forward both to legitimize policy and to fuel criticism, as the case may be. Critics (Dabrowski, 2002; Soto, 2000) have focused mainly on the negative social consequences of these policies for the poor and powerless: economic planning, state capitalism, and protectionism have had few advocates in the 1990s. Considerable efforts have also been devoted to social programs and aid, particularly in the South but also in Eastern Europe, to defuse what otherwise might become a threat to the ultimate goal: stable and orderly but also ‘free’ markets. However, these efforts are limited to selective interventions.

Following Redek & Susjan (2005): “Economic transition is a process of institutional change, a process of building new institutions required by a capitalist economy. The transition brought about the overnight destruction of the socialist coordination mechanism, while the market coordination took time to be established and agents had to become cognizant of it” (p. 995). It is characterized by the liberalization of trade and free markets, the creation and development of private enterprises, and the private sector. The main indicators of transition are large-scale and small-scale privatization, liberalization, foreign exchange system, restructuring of government institutions, banking reforms, and securities markets reforms (EBRD’s 1994 Transition Report 2008).

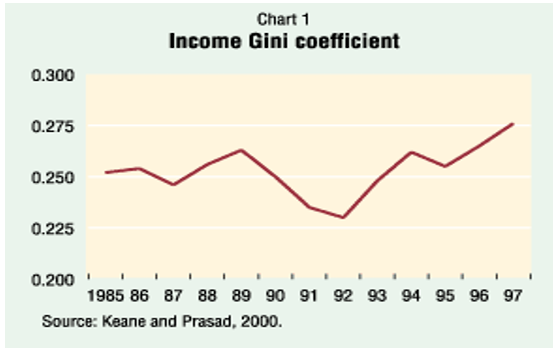

There are cases in market economies when government action is the optimal policy. It is particularly important that the reform programs recognize these areas when the role of government is being reduced (Yeager, 1999). De Melo (1996) underlines that initial conditions determine the nature of change and further economic growth of the country. The researchers single out two main trends in transition: some countries subsidize companies to receive output by fail because of declines in output; price liberalization leads to low inflation rates. De Melo (1997) states that inflation dominates in transition economies caused by their initial conditions and ineffective market structure.

Differences in performance and economic development are explained by inefficient and inadequate government policies in many transition economies. For instance, the inefficiencies of credit and capital markets in transition economies, highlighted above, are linked to the underdevelopment of the legal framework, which at the time was not always able to protect financiers, granting them a fair return for their investments (Dabrowski, 2002).

For this reason, financiers preferred less risky activities, thus neglecting the funding of entering prices. “For example, a nation can have antitrust laws that prevent firms from becoming monopolies, but if the government does not enforce such laws, businesses may act as if the antitrust laws did not exist” (Yeager, 1999, p. 10). As to financing through debt, the main problems are linked to the inefficacy of collateral and bankruptcy laws, which do not fully guarantee repayment to the creditor in case of insolvency. This implies a higher risk for creditors, and therefore, less financing is available for enterprises. The most frequent problems connected to collateral laws are lack of registration rules, unclear lines of priority in case of default, high costs, and a poor secondary market for mobile and immobile goods.

All these problems reduce the expected value of collateral well below its nominal value. Campos & Coricelli (2000) underline that: “The study of the effects of government size on economic growth is highly controversial, to say the least, and the consensus is being built upon the notion that different types of expenditures have different effects on economic growth” (p. 12). This situation leads to forms of credit rationing — profitable projects are not financed because enterprises promoting them do not have sufficient capital to provide collateral (Dabrowski, 2002). This problem is particularly relevant for small and medium enterprises, especially the newest ones, which are insufficiently endowed with capital. Direct government interventions have an important role in this context (Krueger & Ciolko 1996).

Programs of this kind are found in the Czech Republic (financed by the Ministry of Economy, through the Czech and Moravian Bank of Guarantee and Development), in Hungary (Hungarian Fund for Promotion and Development of Small and Medium Enterprises), and in Poland (Fund for Promotion and Development of Small and Medium Enterprises). However, in all three countries, the government is developing appropriate legal measures. In Hungary and Poland, in particular, new regulations, in 1996 and 1998 respectively, provide a uniform system of registration of non-possessive pledges against movable property (Dabrowski, 2002).

“The share of the private sector has expanded in virtually all transition economies and now accounts for a large share of GDP in most economies. There has been a gradual transfer of ownership of previously government-owned assets to the private sector and some reduction in the regulatory burden through the liberalization of prices and foreign exchange markets” (Gupta et al. 2003, p. 554). Differences in initial economic conditions influence market structure and development of the private sector (Dabrowski, 2002).

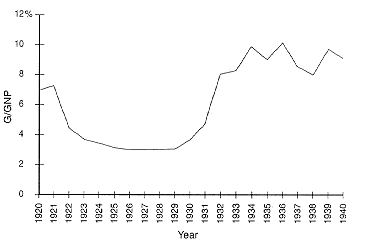

By and large, developing nations have not adequately adjusted their economies, and this neglect has had an extremely adverse effect on LDC efforts to achieve greater balance and order. It is on these grounds that the leaders of the indebted developing countries have characterized the world adjustment process, of which they are but a part, as asymmetrical. Mukand and Rodrik (2002) find that transition economies are compelled to carry the burden of adjustment through retrenchment policies, developed nations are under no such compulsion. ” The private sector has also increased participation in the production of public goods, ah area where the government had hitherto been the sole producer as well as provider” (Gupta et al. 2003, p. 554).

For example, in a few short years, the United States has moved from posting central government budget surpluses equivalent to 0.5 percent of its national output to deficits amounting to the plus-5 percent of GDP (Dabrowski, 2002).

Impact of Initial Conditions and Implementation of Different Policies: China vs. Poland

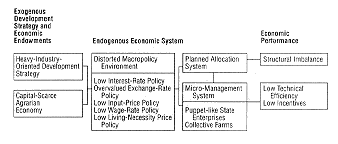

The initial conditions of Poland had a great impact on its performance and further economic growth. Similar to other East European countries, Poland was not influenced by a strong communist regime and government control. “The basic reason for this structural disorder was a defective economic system: Poland’s economy was dominated by the state, closed to the outside world, equipped with false prices” (Woo et al. 1996, p. 131). In contrast to China, Poland had unfavorable conditions explained by a centrally-planned economy based on a strong ideological doctrine. Poland confronted its own adjustment tasks, and its responses on this front had a profound influence on adjustment.

One useful rule of thumb for evaluating a nation’s debt-service performance rests on the relationship between its export earnings and the mean interest rate on its outstanding external debts. If net export revenues increase at a pace greater than the interest rate, the nation’s debt-service burden recedes; if the interest rate is above the expansion of net export value, the burden intensifies (Appendix, Table 1). The IMF’s program for indebted developing countries calls for economic contraction as a prelude to export-led growth, domestic recession, prompting a shift from the production of tradables to the production of exports in the economy.

All things being equal, an expansion in the output of tradables should enable indebted LDCs to increase their export receipts at a pace above that of interest rates, thereby alleviating their debt-service burden. Unfortunately, all things are not equal. For instance, “In China alone, more than two million people have moved from the countryside to the cities since 1979” (Soto 2000, p. 17). But in Poland, rural and urban populations remained stable.

Privatization and formation of the private sector were more successful in Poland. “For all these reasons, Poland opted for a radical economic program. Moreover, in retrospect, it is now clear that output decline in Poland was the smallest among the economies in transition (Appendix, Table 2). Furthermore, an additional note of caution regarding statistical data seems appropriate” (Woo et al. 1996, p. 136, 139). For a time, balance-of-payments deficits can be financed through external borrowing, but since these compensatory flows carry their own balance-of-payments requirements, there are limits on the borrower’s ability to resort to external deficit financing.

In contrast to Poland, in China, the deficit economy must cut its consumption of imports or boost its production of exports or both in order to bring its external accounts into balance; in effect, it must adjust its balance-of-payments toward equilibrium (Appendix, Table 4,5). Such adjustment need not result in a perfect equivalency of income and outgo but must be directed toward a “viable” balance-of-payments position. Because both old debt and new loans impact the borrower’s current accounts, the Fund has an abiding involvement in the debt problems of its member nations (Soto, 2000).

China had poorer initial conditions, but “China’s rapid economic growth can be mainly attributed to the dynamic development of the “new track non-state sector” (Woo et al. 1996, p. 22). Whatever adjustment course they adopt, the results will be strongly affected by external market and policy factors largely beyond the control of these nations. Environmental factors have a pervasive impact on the two major determinants of LDC external debt-service capacity; the cost of debt service itself and the ability of these economies to generate foreign exchange receipts for cross-border loan repayment. “The first supplementary initial condition was that the extent of China’s central planning was much smaller than Russia’s and Poland’s” (Woo et al. 1996, p. 29).

The government policies were more successful in China, able to adapt to the new economic environment in a short period of time. “Of the factors identified above as important causes of China’s achievements in the 1978-94 period, only two factors (China’s integration into the global economic sector and its high saving” helped the country to restructure its economic system (Woo et al. 1996, p. 31). When financing through equities is considered, problems connected to the institutional and legal framework seem to affect firms more than financiers. This form of financing is, in fact, theoretically available for every kind of enterprise.

However, it is expensive to be listed, which makes this form impractical for small- and medium-sized enterprises. The legislation in all three countries requires the firm which wants to be listed to publish certain information concerning its activities, profitability, degree of indebtedness, etc. Public authorities do not check for the quality of the information and do not provide judgments concerning the opportunity of investing in a certain firm.

They only control that the information disclosed is sufficient to allow financiers to evaluate the firm. ” Given the instability and inefficiency of banking systems in transition economies, many basic questions about bank regulation and institutional design remain unanswered or in flux: what bank capital requirements are appropriate, whether free entry into banking should be allowed, etc.” (Gorton & Winton 1998, p. 621).

This is even more true, considering the possibility that an equity issue is unsuccessful, which is still high in Poland. Summing up, the transformation of a banking sector implies high costs and is therefore infrequent. In China, the possibility of financing a firm through the Securities Exchange is a good alternative due to lower costs and information requirements. This alternative is not available in Hungary and in Poland. There is a legal framework concerning financing through venture capital. Managers seeking investment funds try to find external resources in exchange for the promise of future profits.

The investors, however, do not have specific rights of restitution of the invested funds but gain the right over future profits, secured by the right of vote in the decision-making process of the firm. Specific laws protect foreign capital investments by granting the opportunity of profit rescue. While recognizing the role of external capital in the development plans of indebted less-developed countries, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) approaches the debt-service difficulties that they have subsequently encountered not as development (or even debt) problems but as basic balance-of-payments disequilibria.

Nevertheless, in order for indebted developing countries to achieve the trade surpluses they require to affect an easing of their debt-service burdens, they will need sustained and balanced OECD growth. The expenditure decline has been accompanied by changes in the scope of government (Soto, 2000).

The Chinese government was more successful in protectionist policies aimed to improve the position of Chinese goods on the global market. “Extensive trade liberalization is vital to successful trade performance. Most fundamentally, although transition economies clearly faced some amount of protectionism in export markets” (Woo et al., 1996, p. 12). By way of contrast, protectionism against developing-country imports is pointed directly at the export drives mobilized by these nations in the 1980s.

Since the conclusion of the Tokyo Round of Trade Negotiations in 1979, the trend toward greater global trade liberalization has been reversed, with both OECD and LDC governments erecting walls of tariff and non-tariff barriers against foreign imports. The reduction of aggregate demand accompanying the deflation of 1980-83 in the industrialized world dampened consumption of domestically produced goods (Appendix, Table 3). Manufacturers found themselves faced with shrinking markets at home and sought to maintain their shares of contracting markets by stemming the flow of “overly” competitive imports, including goods from debt-burdened developing lands.

In addition to restrictions on imports, many developed nations began to grant subsidies to domestic producers, permitting them to offer goods at prices below their “true” cost and sell surplus production to the government, thereby propping up consumer prices (Soto, 2000; Yeager, 1999).

Both import restrictions and subsidies/price support run squarely against the “free trade” principles embodied in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATR), to which most nations outside the communist bloc nominally subscribe. Applied to indebted developing economies, import protection is neither patriotic nor economically rational. Second, the imposition of tariff duties on foreign goods necessarily entails a cost to the American consumer. Unlike the bill just cited, most protectionist measures normally take an industry-wide form, trade walls being built brick by brick. Among the items that have served as the main targets of protectionism against Poland imports, food, metals, textiles, and wearing apparel are critically important (Soto, 2000).

Conclusion

The success and failures of transition economies are due to differences in initial conditions and different government policies developed during this process. The analysis developed above allows that a direct relationship between the government policies and its initial opportunities for access to external resources are equal. The transition process can explain the severe character of the financing problems faced by small and medium enterprises. In particular, it is shown that the underdevelopment of the banking sector, as well as the ineffective legal framework regulating them, can exacerbate information asymmetries and agency problems.

Financiers do not feel adequately protected and therefore reduce their financing to the less secure firms, the small and medium-sized ones. From an economic policy perspective, the relationship between privatization and liberalization and access to external resources provides a rationale for the development of an active support program for economic development. In Poland, government intervention in their favor is regulated, which supports the development and formation of this kind of productive unit through advance credits and guarantees. In China, the effort to sustain private enterprises has always been much more fragmented due to the lack of a unified law.

Support has usually been provided through the allocation of credit and guarantees. In Poland, the legislative framework in this respect is also quite incoherent. This limits the intervention opportunities and the efficacy of different actions.

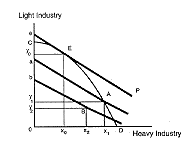

Graphs, Tables, Charts

Bibliography

Campos, N., Coricelli, F. 2000, “Growth in Transition: What we know, what we don’t and what we should”, Journal of Economic Literature, pp. 793-836. Web.

Dabrowski, M. 2002, Disinflation in Transition Economies. Central European University Press.

EBRD’s 1994 Transition Report. 2008. Web.

Gorton, G., Winton, A. 1998, Banking in Transition Economies: Does Efficiency Require Instability? Journal of Money, Credit & Banking, vol. 30, iss. 5, pp. 621.

Gupta, S., Leruth, L., Mello, L., Chakravarti, Sh. 2003, Transition Economies: How Appropriate Is the Size and Scope of Government? Comparative Economic Studies, vol. 45, iss. 4, pp. 554-556.

Krueger, G. Ciolko, M. 1998, “A Note on Initial Conditions and Liberalization during the Transition”, Journal of Comparative Economics, vol. 26, pp. 718-734.

Redek, T., Susjan, A. 2005, The Impact of Institutions on Economic Growth: The Case of Transition Economies. Journal of Economic Issues, vol. 39, iss. 4, pp. 995-998.

de Melo, M. Denizer, C., Gelb, A. 1996, “Patterns of Transition from Plan to Market,” The World Bank Economic Review, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 307-324.

de Melo, M. Denizer, C., Gelb, A. Tenev, S. 1997, “Circumstances and Choice: The Role of Initial Conditions and Policies in Transition Economies”, World Bank Working Paper series No. 1866. Web.

Mukand, Ch., Rodrik, D. 2002, In search of the holy grain: policy convergence, experimentation and economic performance. Web.

Soto, H. de. 2000, The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. Basic Books; 1st edition.

Yeager, T. J. 1999, Institutions, Transition Economies, and Economic Development (Political Economy of Global Interdependence). Westview Press.

Woo, W. Th., Parker, S., Sachs, J. 1996, Economies in Transition: Comparing Asia and Europe. The MIT Press.