An Analysis of the Project’s Structure and Management

The project structure of West Gate Bridge Project had obvious cause of worry from the day it was commissioned.

Taking a simple reflection into the genesis of the project, in 1961, Lower Yarra Crossing Company Limited was established with the sole purpose of seeing to it that either a bridge or a tunnel is developed to ensure that the services of ferry is faced out because its capacity was low.

This company had the original vision for this project. It had the understanding of what was needed and apparently the will and ability to see into it that a bridge was successfully constructed as per the need as at that time. However, the events that led to its closure were not very clear.

Although the report indicates that it went under voluntary liquidation, the immediate replacement by Lower Yarra Crossing Authority, which was affiliated to the government, raises question about the management of the project.

When Maunsell and Partners which was the engineering consultants doubted their capacity to handle the project given its magnitude LYCA acted diligently by contracting the services of Freeman, Fox and Partners (FF&P) which appeared to have greater capacity.

However, the management of LYCA failed to lay a proper structure of how the two consultants would relate. When the two contractors (JHC and WSC) were given the green light to start the construction, again a clear lapse was evident in the structure and management of the project.

Although JHC was able to finish their assigned task without many incidents, it was by lack. The consulting firms failed in their duty to offer guidance to the contractors.

However, because JHC was specialized at the task they were assigned, they were able to sail through their task, especially because their staffs were well coordinated and satisfied with the way the company treated them.

Things were not the same at WSC due to several factors. At first, the structure of the project and the management did not favor them. The joint consultants failed to specialize categorically on which areas to offer their service to this firm. Instead, FF&P took control of everything.

This was in contrary to the spirit of a project structure which, as Daft (2009, p. 123) states, requires every unit to be assigned a specific role that would result in the success of the entire team and not individual’s success.

Maunsell and Partners would have been assigned a distinct role in the project however little the role would be.

The strained relationship between WSC and the consultants, in particular FF&P was an indication that there was a serious problem with the management of the project.

As Sharma (2008, p. 56) says, the management of a given project should have a clear relationship structure for all the concerned members when drawing the project structure.

However, this was lacking and for this reason, WSC complained that FF&P was not releasing all the copies of structural designs that were to be implemented in the construction process.

This resulted in a situation where the engineers of WSC were straining to implement these structural designs. FP&P would be held liable at this early stage of the failure of the project. As a consultant, they were expected to make the work of the contractors easier by giving advice to them at every stage, as Anderson (2011 p. 34) notes.

They were therefore not only expected to release all the copies of the designs to be implemented, but also induct and work hand in hand in the implementation process.

It was to work hand in hand with the contractors, being the overseer of the project. The inability of WSC to manage its employees, which resulted in a strike, further worsened their performance.

When WSC pulled out of their assigned role, there was another dangerous assumption made by the management team of the project. They changed the structure of the project from what was the initial design in as far as the task allocation was concerned.

The success of a team or an individual in its assigned task in the project does not automatically mean that the team or individual can succeed in other departments (Swanson & Holton 1997, P. 167).

By assigning, the remaining task to JHC because of its previous successes was a suicidal move. It became evident after awarding the contract to them that they did not have the capacity and therefore had to rely on the professional services of FF&P.

FF&P given the role to manage employees, changing the initial structure, which had them as consultants in this project. Because of this double role, FF&P failed to notice when the vertical height difference that was between half spans started exceeding the required height, which was 110 mm.

The approach taken by JHC to reverse the mistake was professionally uncouth. Once again, FF&P was on sight as the manager of the workforce besides being the consultant, failed to notice this leading to an ugly incident, which claimed several lives, besides leading to extended time and increased cost of the project.

A Proposal for the Structure and Management of the Project

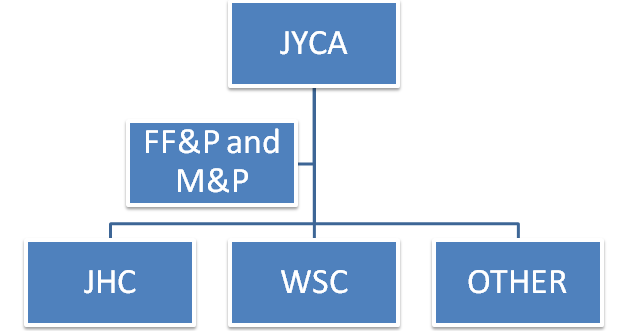

The structure above is a proposal of how the structure of the project should be and how it should be managed. At the top should be JYCA, which is the financier of the project.

It would entrust the work of supervision and consultancy to the two consultants, FF&P and M&P. The two should have a clearly defined role and if possible, the management of the two consultants should work as a single unit.

The effort of each of the consultant should be evidenced at every stage of the implementation process. They will have the task of supervising and assisting the contractors, which are the implementing parties in the project.

Among the contractors, there is a third slot named ‘others’, besides JHC and WSC. JHC and WSC will have their roles as specified in the original structure. They will have to work hand in hand with the two consultants.

They have the responsibility to ask for a technical advice at every stage they feel they need some and they have the responsibility to manage their employees.

As can be seen in the structure, there is a direct link between the contractors and the JYCA which is the overall sponsor of the project and therefore if either of the two contractors have an issue, they can approach the financer directly and so is the financer to the contractors.

The third column for others will be a list of the best losers in the tendering process for the contractors. In case JHC or WSC fails, they may be considered, instead of assigning JHC the roles of WSC or vice versa without determining the capacity to accomplish the task.

List of References

Anderson, M 2011, Bottom-Line Organization Development: Implementing and Evaluating Strategic Change for Lasting Value, Elsevier, Burlington.

Daft, R 2009, Organization Theory and Design, Cengage Learning, New York.

Sharma, R 2008, Change Management, Tata McGraw-Hill Education, New Delhi.

Swanson, RA & Holton, E 1997, Human Resource Developement Research Handbook: Linking Research and practice, Berrett- Kohler Publishers, San Fransisco.