Executive Summary

Mergers and acquisitions are increasingly becoming a novel approach for companies to wade through the competitive pressures of today’s globalized society. The increase of mega-mergers in today’s corporate world demonstrates the entrenchment of such transactions in modern business practices. Since many companies prefer approaching mergers and acquisitions from a professional point of view, the role of advisory firms in supporting companies that intend to merge is evident. This paper investigates the critical success factors for mergers and acquisitions by understanding how merger and acquisition advisory firms measure the success of merger and acquisition projects. This paper also seeks to establish the factors that guarantee the success of mergers and acquisition projects. After conducting a comprehensive literature review and an online survey to gather the views of experts concerning mergers and acquisitions, this paper highlights eight critical success factors for mergers and acquisitions – competence and commitment of project manager, cultural integration, adherence to psychological contract, environmental scanning, human resource competence, identification of the right buyers/sellers, effective coordination of merger and acquisition activities, and meeting the clients’ expectations as the main critical success factors for mergers and acquisitions.

Introduction

Objective and Motivation

There is little contention regarding the idea that most mergers and acquisitions are strategic tools for companies to survive in today’s globalized business environment (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). The importance of mergers and acquisitions in the corporate world stems from their variable advantages, which include increased economies of scale, expansion of the economy of scope, increased revenues, increased market share, development of synergy, geographical diversification, brand strengthening, and reduced taxation.

The financial benefits of mergers and acquisitions stem from cost reductions and increased revenues. Cost reductions may occur in several ways including the elimination of redundant costs and the realization of economies of scale. In terms of increased revenues, mergers and acquisitions may increase the revenue of a company through increased market share, increased customer numbers, and the expansion of company networks (Kim, 2010). However, the realization of economies of scale is perhaps the most important advantage that most companies enjoy from pursuing mergers or acquisitions. As will be mentioned in this paper, the development of economies of scale may occur in several ways including the elimination of duplicate departments or operations and the combination of assets. Companies may also enjoy economies of scale by lowering company costs, relative to the same revenue stream that they may pursue by combining their operations with another company. This way, they improve their profit margins.

The enjoyment of economies of scope closely resembles the realization of economies of scale because economies of scope normally entail changes in demand-side outcomes, while economies of scope include changes in supply-side outcomes. In detail, the economy of scope occurs when demand-side outcomes are made to be more efficient. For example, by increasing the scope of marketing or distribution, a company may make its demand-side outcome more efficient. The increase and expansion of economies of scale and scope normally result in increased revenues and increased market share. However, increased revenue is always a product of increased market share. The main assumption that underlies this relationship is the belief that a merger or acquisition contract eliminates major competitors in the market, thereby increasing the market shares of the remaining companies. Through an increased market power, the dominant company may have more power to control prices and therefore, increase its revenue. This way, companies that have a stronger market share easily enjoy increased revenues.

Close to the concept of increased market share is the advantage of diversification. Diversification often occurs when companies merge or acquire new companies that are not involved in their primary product or service lines. The main aim of pursuing a diversification strategy is to balance the earnings of a company and improve its share price. Some companies also use this strategy to convince conservative investors to invest in their companies (unfortunately, the shareholder value often remains constant in such transactions) (Desai, 2011). Therefore, even though diversification through mergers may be an important concept to adopt, especially in times of economic downturn, it fails to create value because shareholders may similarly enjoy the same advantages of diversification by simply diversifying their portfolios.

The financial benefits mentioned above overshadow other indirect benefits that some companies pursue through mergers and acquisitions. For example, Desai (2011) says that increased synergy and reduced taxation are often elusive advantages that only a few companies enjoy after they merge or acquire another company. As this study will show, synergy occurs when employees work together to attain organizational goals. For example, when companies merge and improve their managerial specializations, there will be increased synergy in the organization. Most companies strive to attain this advantage, but few are successful (Desai, 2011). Besides increased synergy, companies may also enjoy reduced tax burdens when they merge or acquire another company. For example, if a company acquires a loss-making entity, it may receive tax exemptions (Desai, 2011). Lastly, since it is often rare for two (or more) companies to have the same distribution of resources. Mergers and acquisitions provide companies with an opportunity to integrate and distribute their resources in a way that they create value through the process. For example, Desai (2011) says overcoming information asymmetry in today’s world creates value for organizations. The above insights (concerning the benefits of mergers and acquisitions) show that many companies see mergers and acquisitions as possible means to improve their economic and financial positions.

A critical constituent of the success of a merger or acquisition is the role that advisory firms play in M&A transactions. Indeed, as the trend to support mergers and acquisitions increase, advisory firms have been reaping from the trend by earning huge fees for easing the closure of such deals. A common category of advisory firms is investment banks, which provide the financing and expertise to companies that intend to merge or acquire other companies. However, there is a long list of advisory firms because Hoang & Kamolrat (2008) say “M&A advisors may comprise investment banks, corporate lawyers, accountants, stockbrokers, strategy consultants, investor relations and public relations consultants, and environmental consultants” (p. 1). The influence of this group of firms in M&A transactions has captured the attention of many researchers who say that investment banks and brokerage firms may cash in more than $20 billion in M&A transactions alone (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). This figure has soared almost every year because many companies believe that by seeking the services of advisory firms, they will enjoy better terms, conditions, and advice from such firms.

The involvement of advisory firms in M&A transactions is especially profound for small and medium-sized enterprises because they rarely have an in-house advisory department that would guide their managers in making M&A decisions. However, large firms are normally oriented with such transactions and may maintain an advisory department to implement M&A deals. Nonetheless, the maintenance of an in-house advisory department (for large firms) does not mean that the firms do not need the services of advisory firms. On the contrary, large firms sometimes employ the services of advisory firms to better maximize their networks. Similarly, they may use the same firms to enable them to better maximize the potential of their human resource.

Based on the importance of advisory firms in M&A transactions, it is crucial to outline the definition of advisory firms as “the person or company responsible for making investments, and providing advice to investors” (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008, p. 1). Nonetheless, regardless of the categorization of M&A transactions, the description of advisory firms in this paper includes firms that act as intermediaries between the parties involved in a merger or acquisition transaction. These firms then decide to take the role of carrying out the transaction for the client. Examples of transactions that may be undertaken by the firms include buying or selling a firm, advising the client regarding the purchasing or selling process, and structuring or executing the merger.

The main difference between seeking the services of an advisory firm and conducting the M&A transaction without their participation in the provision of in-depth services in the M&A project. Through the provision of such services, many researchers consider the roles of advisory firms to be critical success factors in M&A transactions (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). Stated differently, these critical success factors include the deliverables that most companies have to meet before people can say the projects are successful, or not. Consequently, before project managers guarantee the success of their projects, they must ensure that they understand the role that critical success factors play in their success. Since clients often assign the role of ensuring the critical success factors are met, it is important to comprehend the role of critical success factors, based on the understanding of the role of advisory firms in executing quality and successful M&A transactions. Furthermore, since mergers and acquisitions are highly important for many companies, it is crucial to understand the operational and regulatory challenges that prevent most companies from realizing the benefits of mergers and acquisitions.

Problem Statement

Today, most companies prefer to solidify their market shares, maintain sustainable growth, and overcome their competition through mergers and acquisitions. However, the success of a merger or acquisition depends on many critical success factors that may be elusive for most companies. The failure to understand these critical success factors pose an obstacle for companies that intend to use mergers and acquisitions as strategies for overcoming the pressures of globalization and the intense competition that accompanies it (indeed, globalization may be termed today’s most common accelerator for the adoption of mergers and acquisitions).

Despite the quest by many companies to use mergers and acquisitions as growth and survival strategies, research shows that a few M&A transactions meet their intended objectives (Desai, 2011). For example, Lau, Liao, & Wong (2012) believe that more than 60% of M&A transactions fail to meet their desired goals. Relative to this assertion, Lau et al. (2012) believe that only a paltry 17% of the total M&A transactions (of a global nature) can increase shareholder value. Indeed, history has provided us with several examples of unsuccessful mergers and acquisitions. For example, the airline industry has witnessed several unsuccessful mergers and acquisitions in the recent past, such as the unsuccessful merger between Southwest Airlines and Airtran Airlines, where the companies spent about $0.03 for every $1 they made in the merger (Desai, 2011).

In a similar misfortune, Delta Airlines spent more than $2 for every dollar that is made in a merger with Northwest Airlines (Desai, 2011). In the same merger, Northwest Airlines spent $1.6 for every dollar it made in the merger (Desai, 2011). From these statistics, not every merger amounts to increased profitability or better fortunes for a company. Instead, Desai (2011) persuades us to believe that every merger or acquisition deal has its unique dynamics that inform its success or failure. For example, most mergers and acquisitions are praised because of increased market shares and increased volumes of trade. However, in the airline industry, increased volumes of trade do not suffice as an advantage, but rather, as a disadvantage. Several airline companies have learned this lesson through unsuccessful mergers (like the merger between Southwest airline and Airtran Airline) (Desai, 2011).

From the above statistics, doubtless, firms may fail. However, few people would admit this fact, especially because mergers are known to reduce costs and increase profitability (Desai, 2011). In theory, this may be true because most mergers and acquisitions are designed to merge a few departments and create a “giant” system of organizational departments that would justify the price premium. This logic sounds simple, but in reality, the success of mergers and acquisitions may not be straightforward (Lau et al., 2012). Certainly, If not the elusive goals of mergers and acquisitions, Lau et al. (2012) say that most of such transactions will have their unique disappointments. For example, such disappointments may lead to the plummeting of company stocks. Lau et al. (2012) say that the above outcomes are plausible because the intention of managers to engage in M&A deals may be flawed, or the potential benefits to be derived from such deals may be elusive to many companies. The elusive success of M&A deals informs the purpose of this research paper as it exposes the need for understanding the critical success factors that lead to the success of mergers and acquisitions.

Research Questions

- How do merger and acquisition advisory firms measure the success of a merger & acquisition project?

- What guarantees the success of merger & acquisition projects?

Methodology

This paper relies on case studies, self-completed questionnaires, and semi-structured interviews as the main data collection tools. Through a mixed research approach, this paper analyses information from advisory firms, interviewees, and respondents who give their insights regarding the research topic.

Validity of Data and Sources

Semi-structured interviews and case studies are the main data collection tools for this paper. However, the inclusion of self-completed questionnaires upholds the validity of the information obtained from the semi-structured interviews and case studies. In addition, to guarantee the validity of the information gathered, the findings of the interviews were sent back to the interviewees to ascertain their validity. Most of the findings obtained from the interviews were obtained from the assertions of the respondents, but occasionally some of the findings were inferred, based on the assumptions of the respondents as well. The respondents were carefully selected to participate in the study, based on their knowledge of the research topic.

Mergers & Acquisitions

Mergers and Acquisitions Overview

In the past few years, there has been a significant rise in the number of mergers and acquisition projects in the corporate world. Kim (2010) reports that the increase in the total value of transactions related to mergers and acquisitions highlight the high number of mergers and acquisitions in the business world. For example, in 2007, the value of merger and acquisition transactions was more than $4 trillion (Kim, 2010). Compared to the past years, this value has increased sharply, especially since the same figure was only about $28 billion in the eighties (Kim, 2010).

Similarly, Kim (2010) says that if we compare the proportion of merger and acquisition transactions today and the eighties, we can attest to a significant rise in the share of M&A transactions as a proportion of the sum of business deals. For example, in the eighties, the percentage of M&A transactions was only 0.3%, but this figure has steadily risen to about 10% today. The number of completed M&A transactions within the same period also supports the sharp increase in M&A numbers. For example, only about 10,000 M&A transactions were announced in the eighties, but since 2000, more than 45,000 M&A transactions were completed (Kim, 2010). Kim (2010) has computed this increase and says that M&A transactions grow by about 42% annually.

Since there is a sharp increase in M&A transactions, cross-border transactions have become easier to execute. For instance, businesses have used M&A transactions as a common mode of entry into new markets. Relative to this observation, Kim (2010) says, “The ratio of the value of cross-border M&A transactions to world FDI flows reached 80% in 2007” (p. 432).

Since M&A transactions have become a common part of today’s globalized society, this second part of the thesis aims to explore the nature of M&A transactions and their scope. From this aim, this section includes a comprehensive definition of mergers and acquisitions, an analysis of the different types of mergers and acquisitions, an evaluation of the merger and acquisition process, and an analysis of the development of mergers and acquisitions.

Definitions of Mergers and Acquisitions

“One plus one equals three” (Kim, 2010, p. 1). This statement defines the main logic that informs merger and acquisition transactions. This logic stems from the fact that most companies aim to create a bigger shareholder value than the sum of the shareholder value that would ordinarily be realized if two corporate entities merge. The reasoning behind merger and acquisition transactions therefore stems from the fact that there is a greater value when two companies work together, as opposed to two companies working in isolation. Mergers and acquisitions are therefore joint activities where the activities of two or more companies merge to create one common purpose for both companies.

The purpose of engaging in mergers and acquisitions, as two different business processes, has increasingly become unclear for most businesses. The ambiguities regarding the purpose of both transactions come from the fact that both mergers and acquisitions pursue one ultimate economic outcome – increased profitability. Despite the commonality of purpose, mergers and acquisitions have slightly different meanings, based on their modes of finance.

Mergers normally occur when two companies (usually of equal size) decide to merge their operations. This type of merger is called a merger of equal value; however, such mergers are often rare because, ordinarily, most companies do not have equal value. Instead, one company will purchase another by merely requiring it to state that it is a merger of equal size (although this may not be the case) (Lau et al., 2012). Companies prefer to call such hostile takeovers “mergers,” to sound politically correct, because buying out other companies often bears negative connotations. Concisely, companies often try to disassociate themselves from these negative connotations to make the “buyout” more acceptable to all the parties involved. Therefore, the correct term to refer to such a transaction is an acquisition.

However, the difference between mergers and acquisitions does not only rest in semantics. The modes of agreement between the two or more companies that will merge mainly define the distinction between mergers and acquisitions. Acquisitions differ from mergers because they are often agreeable, unlike mergers where the parties may not be completely conformable with the deal. Sometimes, in mergers, two parties may merge merely because of convenience, or because they have no other alternative, but to do so.

Legally the difference between mergers and acquisitions manifests when one party seizes to exist and another party establishes itself as the new legal entity (this is commonly true for acquisitions) (Kim, 2010). However, for mergers, two companies may decide to conduct businesses as one legal entity, instead of conducting their businesses as two entities. Here, both companies may decide to surrender their stocks and issue new stocks that symbolize the merger between the two companies. Therefore, the legal differences between a merger and acquisition stem from the fact that merging companies may retain some unique operational distinctions, as opposed to acquisitions that completely dissolve the distinctions between the parties. A common example of a merger is the merger between Daimler-Benz and Chrysler. In the merger, both entities were legally seized to exist and a new company, DaimlerChrysler, emerged. Comprehensively, regardless of the nature of the association between two or more companies, the nature of their association mainly defines if the association is a merger or an acquisition. If the association is friendly, then people should regard it as a merger; however, if the association is hostile, people should conceive the association as an acquisition.

Classification of Mergers and Acquisitions

The classification of mergers and acquisitions depends on the nature of the industry and the types of players in the industry.

Types of Mergers

There are different types of mergers, including horizontal mergers, vertical mergers, and conglomerate mergers. This paper explains them below

Horizontal Mergers

Horizontal mergers normally occur when two or more companies that produce similar products merge. Ordinarily, such companies compete against one another and produce similar (or almost similar) products and services. Horizontal mergers are often common in industries where there are only a few players. This type of industry is characterized by intense competition. Therefore, the potential gains of market share in such industries tend to be greater for participating firms. The main motivating factor for companies to pursue a horizontal merger is to create more economies of scale. Again, the merger between Daimler-Benz and Chrysler is an example of a horizontal merger.

The merger between Dubai Aluminum and Emirates Aluminum is also another example of a horizontal merger of different companies that operate within the same industry. The details of the merger show that both companies disowned their individual identities to form a larger company, Emirates Global Aluminum Company (analysts expect the company’s total value to be more than $15 billion, setting it among the biggest aluminum companies in the world) (Cooper, 2013). Analysts also expect the new company to start its operations in the first half of 2014 (Cooper, 2013). The horizontal merger has also received immense support from the government.

The CEO of Dubal company will manage the new company, but he will be helped by the management teams of Emal Company as well. Consequently, many observers say that the horizontal merger will benefit from a very diverse management team that has a lot of experience in the aluminum industry (Cooper, 2013). This merger has created a whirlwind of speculation regarding more impending mergers between other UAE and Middle East companies. For example, since the Dubal and Emal merger is set to reduce the cost of operations for both companies, some analysts say Emirates Airlines and Etihad airlines should also merge in the same fashion and enjoy the same advantages (Desai, 2011). Nonetheless, these mergers show classic examples of horizontal mergers of companies that operate in the same industry.

The prospective merger between Al Dar Properties and Sorouh real estate is also another example of another horizontal merger because both companies operate in the real estate sector. This merger was only recently approved by the board of directors of both companies and is now awaiting the approval of the government (through the approval of the Abu Dhabi Executive Council) (Peters, 2012). Unlike most mergers that involve two companies with unmatched economic potential, the merger between Al Dar Properties and Sorouh Real estate is a merger of equals. The boards of directors of the two companies therefore believe that the merger will create a reliable platform for the development of sustainable growth (Peters, 2012).

Even though there is a lot of optimism surrounding the merger, it is also important to mention that the merger has been proposed when the industry’s performance is still low. The performance of the sector is low because the UAE real estate sector has never really recovered after the 2008 economic downturn (Peters, 2012). The poor performance of the sector has caused many companies in the industry to restructure their operations and devise better ways of managing their debts (this is why horizontal mergers are common in the industry). The idea behind merging the two companies when the industry is not at its best is therefore appealing to some of the proponents of the merger because they expect that the merger may decrease overheads by combining some assets. In the same way that this merger may be beneficial for both companies, some of its proponents say that it may provide a better platform for the emerging company to control prices (Peters, 2012).

However, despite the existence of extensive optimism about the merger, an independent researcher, Peters (2012), says mergers may not necessarily solve the problems they are designed to solve. Instead, the mergers may merely create a larger company that buries old problems but fails to solve them. For example, a proposed merger between two equally big real estate companies, Emaar and Dubai properties was rejected by shareholders when they realized that the merger would create serious operational and shareholder issues (Peters, 2012). Peters (2012) fears that the merger between Al Dar Properties and Sorouh Real Estate Company may lead to a similar outcome.

Horizontal mergers are often criticized for their ability to reduce competition (Cooper, 2013). This outcome often manifests because the number of potential rivals in the industry declines significantly if two or more mergers occur in an oligopolistic market. Even though the creation of anticompetitive effects may be true, horizontal mergers do not necessarily have a bad effect on the economy. For example, Desai (2011) posits that horizontal mergers decrease average costs of operations and increases the market power of companies in the industry (especially those that have merged). Nonetheless, Desai (2011) cautions that market power and cost savings are not easy to determine. Similarly, market power and cost savings are often not typical for most mergers.

Vertical Mergers

Vertical mergers normally occur when different companies in a production chain merge their activities to make the production process more efficient. There are numerous examples of vertical mergers. Among the oldest and most common examples of a vertical merger is the merger between Carnegie Steel Company merger and several associate companies to control the entire chain of its production process (Marks, 2013). The vertical merger allowed the Carneige Steel Company to control the steel production mills, the extraction of the iron ore process, the supply of coal, the transportation of iron ore, and the coal “cooking” process. Furthermore, through the same vertical merger objective, the Carneige Steel Company started to develop its internal talent as opposed to searching for the same talent outside the company.

Conglomerate Mergers

Unlike horizontal mergers, conglomerate mergers normally occur when two or more firms, operating in different industries, merge. A classic example of a conglomerate merger occurred in the early sixties when a telecommunications company, ITT, diversified its operations by merging with “Bought Hartford Fire Insurance, Continental Baking, Sheraton Hotels, Avis Rent-A-Car, Canteen vending machines, and 100 more companies” (Marks, 2013, p. 19).

Some people consider conglomerate mergers to be important types of mergers because they increase managerial efficiencies. This outcome often suffices because the failure to increase managerial efficiencies may result in hostile takeovers or the replacement of inefficient managers with efficient managers. The following table shows the classification of M&A transactions

Classification of M&A.

Types of Acquisitions

The main types of acquisitions are asset acquisitions and stock acquisitions.

Asset Acquisition

In an asset acquisition, one company normally sells strategic assets to the acquiring company. Such an asset acquisition process occurs when the acquiring company prefers to choose specific assets of a company and shuns other assets that it does not want responsibility for. The types of assets to be acquired may include tangible assets, such as office furniture, and intangible assets, such as goodwill. It is often difficult to transfer these assets because of the difficulties in valuation, the payment of transfer taxes, or the involvement of interested parties (especially in government contracts) (Marks, 2013).

Stock Acquisitions

Stock acquisitions involve the transfer of stocks of the selling company to the acquiring company. Unlike asset acquisitions, stock acquisitions are not difficult to execute because stocks are often transferable based on their current values (Marks, 2013). As such, there is no tedious process of valuing the assets. In addition, unlike the asset acquisition process, the seller does not receive any asset step-up tax; instead, the seller incurs the tax on a carryover basis (usually the goodwill created from a stock acquisition is not tax-deductible) (Marks, 2013).

Merger and Acquisition Process

The process of completing a merger or acquisition is often a significant undertaking for any company. Therefore, it is usually important for companies to ensure that the process of merging or acquiring a new company is flawless. However, this task is usually very intimidating for most companies, but fortunately; the process is a detailed step-by-step undertaking.

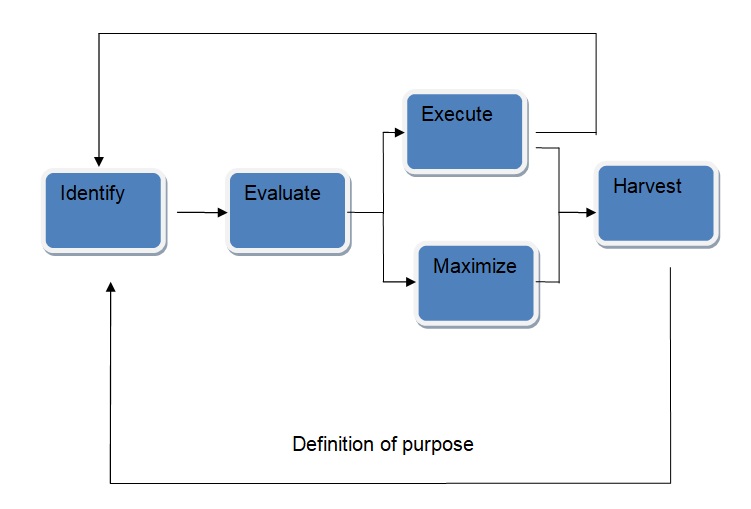

Many observers have used several M&A models to explain the M&A process. For example, the Watson Wyatt Deal Flow Model contains a five-step model that has been used to explain most M&A processes (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). The model involves the analysis of the different stages that occur in the same horizon, but have a strong goal of ensuring there are correct and timely inputs into the entire M&A process. These stages are explained below

- Step 1: When companies intend to make M&A transactions, they consult advisory firms to guide them through the entire process. The main role of these advisory firms, as explained in subsequent sections of this paper, is advisory. It is through this role that the advisory firms establish the main vision of the company, its goals, and how the company may attain these goals through strategic foresight (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). The advisory firms, therefore, provide the clients with a strategic foresight to show the M&A process flow and how this flow helps the company to achieve its goals. Occasionally, some companies may decide to sign the consultancy contract before the advisory firm provides them with a clear strategic forecast of the M&A transaction, but often most companies prefer to see this forecast to evaluate their needs, viz-a-viz what the company offers, to determine if they should sign the contract, or not.

- Step Two: The evaluation process is the second step of Watson Wyatt’s Deal Flow Model. The evaluation process involves the evaluation of the companies involved in the merger or acquisition process, based on their assets, liabilities, or equity, to establish how the optimum value of the company may be realized (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). Taxation and legal matters of the deal may be explored at this stage. The wishes of the companies involved in the merger, and the nature of the intelligence gathered during the evaluation stage, often forms the premise for understanding how the execution of the merger will occur.

- Step Three: The execution stage outlines the third step of Watson Wyatt’s Deal Flow Model. The execution stage is often very important for merger and acquisition transactions because advisory firms recommend the course of action to take during a merger or acquisition at this stage (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). For example, an advisory firm may recommend that a company should sell its equity to the public, or to another company at this stage.

- Step Four: The harvest stage outlines the fourth step of Watson Wyatt’s Deal Flow Model. The role of the advisory firm is often complete once a company sells to the public or the merger deal is complete. However, some advisory firms may participate in the integration process to ensure that the full implementation of the details of the merger. Regardless of the situation, the completion of a merger is a learning lesson for advisory firms. Indeed, by knowing all the details surrounding a merger or acquisition, the firm may refer to these details for the execution of future contracts. A snapshot of the above merger and acquisition process is as designed below

Besides the outline of Watson Wyatt’s Deal Flow Model, Snow (2013) outlines a different set of steps that different companies should follow in the M&A process. He says that the first step in any merger or acquisition process is the identification of a suitable buyer or seller. The second step of the process is contacting the seller about the deal. This process is often crucial for the future of the deal because, at this point, it is easy to determine the level of interest for the seller or the buyer. This way, it can be equally easy to establish if proceeding with the process is feasible, or not. Snow (2013) says that pitching the right deal for a seller or a buyer is often a difficult process, especially for the buyer.

The third step of the M&A process involves receiving or sending a teaser (executive summary) of the entire deal. This teaser provides the customer with just enough information to capture the interest of the buyer or the seller. The aim of the teaser is to make the seller, or the buyer, want to learn more. Later, both parties should sign a confidentiality document to affirm that the contents of their discussions will be confidential. Both parties should also review the confidential information memorandum (CIM) that discloses important information about a company (such as the products, financials, and history of the company) (Snow, 2013). The aim of this process is to pre-empt an offer. After making an offer, either the seller or the buyer should make the offer with a specified range of valuation, as opposed to a specific price.

After comparing the compatibility of the intentions of the seller and the buyer, based on the contents of the CIM, the seller or buyer should submit a letter of intent. Usually, the seller or buyer quotes a fixed price in this letter (Snow, 2013). Depending on the addressee of the letter, the seller/buyer should conduct due diligence to ensure that all the information provided in the agreement is accurate. After confirming the details of the agreement, both parties should draft the purchase agreement and sign it. The acquisition or merger is thereby completed and the seller/buyer evaluates how the new entity fits into the existing business model.

The Development of Mergers and Acquisitions

The history of mergers and acquisition transactions date back to the formation of companies in the 19th century. Among the earliest forms of mergers and acquisitions occurred in the late 1700s, but among the earliest waves of mergers and acquisitions occurred in the late 1800s and early 1900s (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). The earliest merger wave mainly involved small companies in America, which merged to form bigger and more powerful companies. Historians estimate that about 1900 small firms in the US consolidated their operations during the same period and gained significant market share as a result (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). The small companies merged through the creation of small “amalgamation” bodies – trusts.

To understand the sheer volume of mergers and acquisitions that happened during the late 1800s and early 1900s, it is important to mention that the total value of all the firms that were acquired in the mergers reached 20% of America’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). Comparatively, this value was only 3% in 1990, and only about 10% in 2000 (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). It is therefore inevitable to say that the volume of mergers and acquisitions that happened in the late 1800s and early 1900s was among the largest in history.

The significance of the 1800/1900 wave of mergers can be felt today through the dominance of companies that were formed during this period. For example, DuPont, US Steel, and General Electric (GE) are some of the companies that emerged during the 1800/1900 merger period and they still dominate their markets, somewhat, today. Other companies however collapsed on the way because of intense competitive pressure. For example, International Paper, and American Chicle are examples of some strong companies that emerged during the merger period but collapsed along the way because of intense competitive pressures (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). It is important to mention that most of the companies that merged during this period merely did so because it was the trend at the time, but not because they wanted to improve the managerial efficiencies (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008).

Since the 1800/1900 merger wave, several waves of mergers have occurred later. The second wave of mergers happened between 1916 and 1929 (many of these mergers were vertical mergers because horizontal mergers mainly characterized the first wave of mergers) (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). Later, between 1965 and 1969, the third wave of mergers occurred. This wave of mergers included diversified conglomerate mergers. The fourth wave of mergers occurred in the late eighties when congeneric mergers and hostile takeovers occurred in the corporate world. However, as globalization started in the nineties, cross- border mergers characterized most types of mergers. This period was later replaced by shareholder activism, and private equity development, which characterizes most of the mergers we see today (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008).

Critical Success Factors for Projects

Critical Success Factors for Projects

To understand the critical success factors that inform M&A projects, it is crucial to highlight the distinction between critical success factors and project success criteria. Critical success factors are mean to determine the success or failure of M&A projects because they can either simplify or impede the realization of M&A goals. Project success criteria are management tools that show if a project is successful, or not. Critical success factors and project success criteria share a close relationship because the proper execution of critical success factors normally leads to a positive rating of project outcomes (through the project success criteria). To affirm the distinction between CSFs and project success criteria, Hoang & Kamolrat (2008) elaborate that “critical factors can be perceived as catalytic or impeding conditions which influence the project outcome, while project success criteria can be viewed as a set of measurements agreed among stakeholders to assess the project outcomes” (p. 17). Broadly, project managers may use critical success factors as possible tools for influencing project success criteria. In addition, project managers may use critical success factors as a set of measurements to define the project success criteria.

This section of the thesis divulges details regarding project management as a critical component of understanding the factors that inform the success of mergers and acquisitions. To draw the relationship between these project factors and M&A decisions, this section of the report outlines the critical success factors, lists and frameworks for project success, critical success factors for a particular industry, and the critical success factors for mergers and acquisitions

Critical Success Factors, Lists, and Frameworks

Project managers have always tried to encompass the concept of critical success factors (CSF) in its philosophical framework. Initially, the concept of CSF mainly depended on theoretical assumptions, but later, this changed. Now, CSF mainly depends on empirical facts. In the late seventies and early eighties, CSF was mainly approached through the understanding of the factors that influence project success (Marks, 2013). Such factors included time, cost, quality, stakeholder satisfaction (among other factors). The project implementation profile (PIP) model was the first framework that outlined a set of reliable CSF factors that would assess project success. The same model also provided project managers with a reliable set of measurement tools for assessing project success. The CSF factors that the PIP model identified were “project mission, top management support, project schedule/plan, client consultation, personnel, technical tasks, client acceptance, monitoring and feedback, communication, and troubleshooting” (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008, p. 22). The importance of the above CSF factors is crucial for the entire period of the project, although their relevance varies, depending on the lifecycle of the project. The importance of the above CSF factors also varies, depending on the nature of the organization, its direction, and where it intends to be.

Hoang & Kamolrat (2008) say that the above CSF factors may subdivide into strategic factors and tactical factors. They say “Project mission, top management support, schedules, client consultation” (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008, p. 21) are strategic factors, while tactical factors define the rest. The relevance of a strategic or a tactical factor varies in importance, depending on the project stage and the type of project performance measurement.

The main weakness of the PIP model is its failure to consider external factors of project management, like the “competence of the project manager, political activities within the organization, external organizational and environmental factors, and response to the perceived need of project implementation” (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008, p. 21). These weaknesses have a significant impact on project success because Marks (2013) says the ignorance of external factors in project management may cause adverse project outcomes. Conversely, if project managers consider these external factors in project management, they are highly likely to realize a favorable project outcome.

Many researchers who delved into the issue of CSF in project management (in the nineties) intensely explored the impact of stakeholder involvement in project success (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). The same group of researchers also recommended that it is important to integrate CSF categorizations with project success factors to have a comprehensive framework for assessing project success. Marks (2013) say that most of the CSF factors that have been proposed by previous researchers have adopted a narrow scope of project success factors because they have only focused on project managers and project organizations. They have therefore failed to include other key project success factors, such as the characteristics of the project, the commitment of team members, and other external factors in their analysis of project success factors (the inclusion of these factors would provide a new categorization of CSF factors). The outcome would be the inclusion of four categories: project, project managers and team members, organization, and external environment (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). The formulation of these new categories also gives room for the project manager to assess the different intra-relationships that define project success.

In the above analysis, it is important to classify which project factors explain the success of an individual project and which success factors are critical to the overall success of the project management process. In the same lens of analysis, it will be easy to establish which factors lead to consistent project success. Some researchers have further differentiated factors that lead to project success and the factors that lead to project management success. The main basis of distinction is the measurement tools used to assess both categories. For example, Hoang & Kamolrat (2008) say that the success of the project management process mainly depends on evaluating if it meets the criteria of time, cost, and quality. However, the criterion for assessing project success depends on its extent in meeting project objectives.

Researchers who support the above views have come up with 12 CSF factors that they have developed from years of practice, by evaluating different projects in large multinational organizations (Marks, 2013). The researchers also developed these critical success factors by changing project scopes and maintaining the integrity of the performance measurements. In detail, the researchers have shown that most “people factors” are important in understanding project success (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). Relative to this assertion, Hoang & Kamolrat (2008) outline four critical success factors that should inform project success. They include,

“A common understanding of the success criteria before starting a project, a high level of collaboration between the project manager and the project owner, adequate empowerment for project manager, and sufficient project performance” (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008, p. 22).

In terms of solving the problems related to project management, Hoang & Kamolrat (2008) propose that project manager should involve “effective communication, clear project’s objectives and scope, decomposing projects into manageable sizes, and using project plans as working documents” (p. 22) to solve project management problems. A similar set of CSF factors for project management has been proposed by a renowned researcher, Nicholas (cited in Marks, 2013) when he proposed that CSFs may be classified into three categories “project participants, communication and information sharing and exchange, and the project management/systems development process” (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008, p. 22).

The focus on critical success factors in project management has led to the diversification of disciplines, including the development of total quality management (TQM). The European Foundation of Quality Management and the Formal System models have also developed from the same focus (Marks, 2013). Researchers have developed these models to improve the project management process (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008, p. 22). For example, several researchers have used the European Foundation of Quality Management Model to construct the framework of critical success factors that concern an organization, such as “leadership and team development, policy and strategy development, stakeholder management, resource use, contracting, and project management factors” (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008, p. 22).

Some analysts have compared the European Foundation of Quality Management model to other models such as Pinto and Slevin’s model of quality management (Marks, 2013). However, the difference between Pinto and Slevin’s model and the European Foundation of Quality Management model is the absence of resource and contract factors. The European Foundation of Quality Management model is also unique to other models because it not only includes project success criteria but also includes external factors that affect the project success criteria. In a study conducted by two researchers, Fiortune and White (cited in Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008), it was established that most projects which have a lot of CSFs have a higher degree of success than the projects that have few CSFs (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). The researchers established this finding after comparing two information system projects (Marks, 2013). In this regard, it is correct to say that CSFs do not merely guide project managers to undertake successful M&A projects because they also provide a reliable set of standards for the evaluation of M&A projects.

As witnessed in the above analogy, many researchers have mentioned critical success factors in their analyses. The mentioning of these critical success factors in extensive literature has prompted many project managers to conceptualize them as critical success processes. Their importance especially manifests in the planning stage. At this stage, the project managers outline the processes that need to be followed to achieve the objectives of the project. Hoang & Kamolrat (2008) say that it is usually prudent to pay close attention to these processes at the planning stage, as opposed to the execution stage because it would be expensive to change the direction of the project at the execution stage. Above all, the planning process is critical to the effective execution of the project.

Regardless of the importance of CSFs at the planning stage, it is of grave importance to understand that not all CSFs have the same relevance during the planning stage. Two researchers, Zwikael and Globerson (cited in Marks, 2013) have conducted research to evaluate the significance of CSF factors in the project planning phase and found out that there are six important CSF factors, “activity definition, schedule development, organizational planning, staff acquisition, communication planning, and project plan development” (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008, p. 23).

Hoang & Kamolrat (2008) noticed a significant weakness of past literature regarding critical success factors. They noticed that past literature disregarded project success criteria in their analyses. However, recent studies have tried to solve this problem by bridging the gap between project success criteria and CSFs because many modern researchers agree that both concepts have a significant impact on project management studies (Lau et al., 2012). Nonetheless, there is no standard definition of critical success factors because different projects require different critical success factors to succeed. Hoang & Kamolrat (2008) argue that most present-day critical success factors are more dynamic and complex than previous CSFs. Relative to this claim; they say that past CSFs never included the “hard” and “soft” aspects of project management (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). Comparatively, many CSFs today include “hard” and “soft” aspects of project management, such as, “the competence of the project manager and the project team members, leadership, behavior, and address all perspectives of project management such as quality management, risk management, stakeholder management, project portfolio management, and program management” (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008, p. 23).

Critical Success Factors for a Particular Project/Industry

Researchers who have studied CSFs have developed vast literature to conceptualize different critical success factors for different industries. Depending on the nature and type of industry, different researchers have compared the CSFs for different projects. For example, Jang and Lee (cited in Lau et al., 2012) have tried to understand the CSFs for consulting projects by coming up with three sets of CSF variables. These variables are the competence of the consultant, consultation mode, and the characteristics of the client’s organization (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). However, Jang and Lee (cited in Lau et al., 2012) say that these CSFs do not necessarily have to be found within the project organization because external factors also have the same significance in project management. Nonetheless, project success mainly depends on the interaction between different sets of variables “project manager, team members, parent organization, and customer organization” (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008, p. 26).

Many groups of researchers propose that CSFs often vary in importance, depending on the industry where they operate. For example, in the manufacturing industry, the skills of the project manager surface as the most important critical success factor. Similarly, in the construction industry, weather-related factors surface as the most important CSFs (Marks, 2013). In the information technology industry, all factors are considered to be CSFs, except for client acceptance, but in the engineering sector, client acceptance and project mission surface as the most important critical success factors (Marks, 2013). In the same industry, scope definition and cost planning also emerge as important critical success factors. The importance of client acceptance as a pivotal CSF factor in many industries also surfaces as an important critical success factor in the construction industry, especially when it merges with monitoring and control factors.

Based on the relative importance of critical success factors of different industries, Zwikael and Globerson (cited in Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008) establish that project planning is an important CSF that transcends different projects, regardless of the industry (they made this realization when they tried to rank CSFs). The definition of activities and the development of project schedules however surface as more important CSFs, especially in the service sector. Similarly, in the same service sector, quality and communication planning have also surfaced as important critical success factors in the industry. The nature of the service industry as a platform for stakeholder interaction informs the importance of quality and communication planning as critical CSF factors in the service industry (Lau et al., 2012).

The understanding of CSFs is often a very dynamic undertaking because there is no common framework for understanding CSFs. Similarly, different researchers often propose unique sets of CSFs, depending on their conceptualizations of the same (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). Nonetheless, the project management theory is the main point of commonality between a practitioner and a researcher. The project management theory suggests that the process of understanding CSFs needs to comprehend three main issues – their relative importance in different phases of the project cycle, the importance of understanding the interrelationships among different CSFs to achieve project success, and the varying importance of different CSFs across different industries (Lau et al., 2012).

Critical Success Factors for Merger & Acquisition Projects

Understanding the critical success factors for a merger or acquisition mainly depends on a thorough understanding of the factors that lead to M&A failures. Indeed, albeit it is important to adhere to CSFs for M&A success, it is also important to avoid the pitfalls of M&A processes. In the spirit of understanding the possible pitfalls that lead to M&A failure, many researchers have tried to investigate the main causes of M&A failures. Most of them have come up with varied findings. In one study, a consultant who has specialized in mergers and acquisitions, Gadiesh (cited in Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008), says the “poor understanding of the strategic levers, overpayment for the acquisition (based on overestimation of enterprise value), inadequate integration planning and execution, a void in executive leadership and strategic communication, and a severe cultural mismatch” (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008, p. 28) are the main causes of M&A failures.

Similarly, another researcher, DiGeorgio (cited in Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008) also argues that “inadequate due diligence, lack of compelling strategic rationale, overpayment for the target company, conflict between corporate cultures and failure to meld two companies” (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008, p. 28) are the main causes of M&A failures. Meanwhile, Hoang & Kamolrat (2008) posit that “The inability to realize projected economies of scale, and the failure to integrate people, processes and systems” (p. 28) explain why many M&A deals fail to achieve their objectives.

Lau et al. (2012) also, believe that booming financial markets often create the platform for the development of flawed intentions among company mergers when they engage in M&A deals. In other words, many companies are motivated to merge when the stock market is vibrant, even though the strategic thoughts behind the mergers may be weak. Such cases are often characterized by corporate trends that symbolize a common “peer attitude,” whereby business executives participate in mergers because other companies are doing the same. Here, such mergers pursue “glorious” outcomes, as opposed to the development of successful business strategies. Lau et al. (2012) especially highlight ego “boosts” as possible benefits that most executives pursue, simply because they have managed to buy out a competitor from the market. An assortment of legal minds and bankers who earn huge fees from such mergers often fuel this trend by giving wrong advice to business executives for financial gain. These business executives also fall for these “advisors” because they want to be the “greatest” and the “best” in the business. Unfortunately, most of these executives receive a huge bonus after securing such flawed deals, even when the deals turn out to be harmful to the company in the end.

In an unrelated context (and what drives most companies today), the failure to merge or assent to an acquisition deal evokes a strong fear that it may mark the end of a company (Lau et al., 2012). This fear informs most merger and acquisition deals. Such generalized fears have emerged from the rapid entrenchment of globalization, the development of technology, and the growth of competitive pressures. Such pressures often give “defensive” managers a reason to assent to merger and acquisition deals. The idea behind such a decision is the assumption that only big players survive in a competitive world and small companies have no choice, but to merge with another company, or wait for a hostile takeover.

Comprehensively, the above researchers agree that M&A failures mainly stem from one (or a combination) of the following factors “The lack of the right strategic rationale, insufficient analysis or assessment during the early stage, overpayment which cannot be justified, and poor management in the integration phase as a result of lack of experience and prior planning” (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008, p. 28). The understanding of the factors that lead to M&A failures therefore provides the bedrock for understanding the critical success factors for mergers and acquisitions as outlined below.

Environmental Scanning

Lau et al. (2012) strongly believe that if managers decide to conduct a thorough environmental scan before they commit themselves to mergers and acquisitions, they would possibly avoid the failures associated with M&A transactions. Environmental scanning is used in this context to refer to the understanding of social and cultural factors that affect M&A decisions. The concept of environmental scanning also involves understanding the trends and relationships that characterize the external environment of an organization. The comprehension of these environmental factors should be a pillar for supporting key managerial decisions (M&A decisions). The importance of this process mostly suffices in turbulent economic times because continuous environmental scanning is an important tool for informing managerial decisions.

Lau et al. (2012) propose that, in today’s information age, managers should use internet tools such as web 2.0 to gather information regarding the market, before they sign M&A deals. Web 2.0 tools could easily help to provide user-generated qualitative information that would be useful in executing M&A transactions. Indeed, it is easy to find huge volumes of information regarding socio-cultural and political issues about specific companies or industries online. Relative to this assertion, Lau et al. (2012) say, “Top executives and M&A consultants have unprecedented opportunities to tap into valuable business intelligence (for example, the socio-cultural knowledge about a targeted market) by continuously scanning the Web 2.0 environment” (p. 1263).

Grounded in the porter’s five force analysis Lau et al. (2012) propose that the novel due diligence scorecard is useful in improving managerial decision-making skills, especially in improving or executing merger and acquisition transactions. In the same context of improving managerial decision-making processes, Lau et al. (2012) propose that an adaptive BI 2.0 tool should be used to support the scorecard model. The BI 2.0 tool is beneficial for scanning the environment using web 2.0 tools because it is effective and has outperformed other Known base-line methods of scanning the business environment.

A look at M&A transactions in the Chinese business context shows that prototype systems may be useful in streamlining the environmental scanning process to make it more efficient (Lau et al., 2012). This way, decision-makers find it easier to make M&A decisions. A plausible advantage that is associated with this method is its adaptability to different business contexts. Moreover, since BI 2.0 technology works through unsupervised sets of statistical techniques, it may be easy for managers to apply this tool across other business activities that are related to M&A transactions, such as “financial risk identification, bankruptcy prediction, and investment portfolio management” (Lau et al., 2012, p. 1264). Based on these capabilities, it is correct to say that BI 2.0 technology is very useful, especially in situations where there is scanty information regarding the target market.

Psychological Contract Violation

Every year, thousands of companies participate in merger and acquisition deals that redefine their business processes. However, beyond the economic cost of such a deal is the human aspect of merger and acquisition projects. Most of these human aspects of M&A deals revolve around the prevailing consequences of M&A transactions for individuals and organizations alike. Concisely, M&A transactions affect millions of people and organizations because of Roundy (2010) says M&A transactions are synonymous with layoffs, intercultural conflicts, redefinition of employee roles and responsibilities, and the imposition of new forms of managerial structures.

Most employees do not know if a merger or acquisition may bring the above ramifications or how the implications of these ramifications may affect their careers. These uncertainties may lead to the development of individual uncertainties that may manifest in the alteration of several individual outcomes such as “job satisfaction, job performance, stress, and turnover intentions” (Roundy, 2010, p. 88). Mergers and acquisitions especially have a profound impact on these outcomes.

There is a great consensus among most researchers that M&A transactions have a significant impact on employees’ commitment to an organization (Roundy, 2010). This effect manifests because M&A transactions affect the emotional commitment of workers to an organization. The commitment of an employee to an organization is important to the success of a merger or acquisition because employee commitment affects the “behavior, perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, and the job performance” (Roundy, 2010, p. 89) of workers. More specifically, the level of employee commitment to an organization may lead to the success or failure of a merger or acquisition. Usually, low levels of commitment to an organization lead to unfavorable outcomes in M&A transactions. This relationship means that the companies that engage in M&A transactions have a difficult task ahead of them because their M&A transactions are bound to decrease employee commitment to the organization. Unfortunately, a reduction in employee commitment reduces the performance of M&A transactions. To support this assertion, Roundy (2010) argues that

“By choosing to engage in a merger, a firm is setting into motion a process that, in its typical course, limits the success of its primary outcome. And, given the precarious success rate of M&As, organizations certainly do not benefit from an additional factor that negatively influences the likelihood of M&A success” (p. 89).

The problems facing most organizations in M&A processes concern how they can increase the level of employee commitment to the organization. Furthermore, if a company manages to do so, the second dilemma that would affect such an organization is the identification of the right mechanism for improving employee levels of commitment. After evaluating these dilemmas, Roundy (2010) does not hesitate to say, M&A transactions decrease the level of affective commitment. In part, this outcome suffices through the shift in employee regulatory focus.

The anxiety and uncertainty that characterize mergers and acquisitions also have a negative impact on the performance of the transactions because employees tend to prevent their success, as opposed to promoting them. Relative to this observation, Roundy (2010) suggests that most companies should strive to influence (positively) the perception of their employees, regarding mergers and acquisitions, so that the employees may equally improve their levels of affective commitment. The best way to do so is by changing the communication strategy between the company and the employees because effective communication strategies can adequately influence employee perceptions regarding the merger or acquisition process. Researchers have specifically highlighted communications with a narrative structure as the best type of communication strategy for improving the level of an employee’s affective commitment to the organization (the advancement of promotion-focused narratives should prevent the negative influence of merger and acquisition activities, thereby boosting the performance of M&A transactions) (Roundy, 2010).

A key issue that most researchers have neglected in the above analysis is the influence of psychological contract violation in influencing the perception of employees in M&A transactions. Analysts outline the psychological contract violation as the perception among employees that M&A transactions have failed to honor their psychological contracts (Roundy, 2010). The psychological contract violation has a close relationship with trust because trust is the willingness of new employees to accept “frangibility,” based on the intention and the aims of the companies involved in the merger or acquisition. The psychological contract violation may manifest in different aspects of M&A transactions, including transactional violations and relational violations. The transaction violation normally occurs when the employees have a strong belief that the merger or acquisition ignores their material or economic interests, while relational violations refer to the belief that the merger or acquisition fails to provide the employees with a stable relationship for their interaction with the company (Roundy, 2010). Yan & Zhu (2013) say that the “perceptions of both violations cause employees to experience disappointment, resentment, and to perceive unfairness” (p. 494).

The impact of the above violations on the success or failure of M&A transactions manifests when such violations affect the tasks, responsibilities, and interpersonal relationships among employees. Usually, when this happens, the human resource of an organization is severely affected. This effect may manifest in different forms, but the resignation of workers is perhaps the most common effect of such violations. Indeed, Kim (2010) says that psychological contract violations in mergers and acquisitions have in the past led to the resignation of managers and employees. Although unspecific on the reason for resignation, Kim (2010) says that most mergers and acquisitions lead to the resignation of directors and ordinary employees. For example, a study by two researchers, Franks and Meyer (cited in Kim, 2010), in the UK, showed that about 88% of directors resigned when there was a hostile takeover in their companies. Similarly, 50% of directors resigned when there was a friendly merger between two or more companies (Kim, 2010). Past literature shows that most mergers and acquisitions in the UK have a negative impact on the labor market because they lead to the reduction of labor demand. Past literature that has focused on the US manufacturing sector also shows that most mergers and acquisitions may lead to severe job losses. Given that most mergers and acquisitions lead to significant job losses, it is unsurprising that many workers perceive M&A transactions with a lot of suspicion and mistrust, especially about their well-being.

The importance of psychological contract violation manifests as an indicator of the failure of managers to include the non-financial aspects of M&A mergers into the execution of the deals. Yan & Zhu (2013) have investigated the effect of psychological contract violations in M&A transactions by understanding their effects on the attitudes and motivations of employees. The researchers said that the nature and characteristics of M&A transactions have a significant psychological impact on the workers involved (Yan & Zhu, 2013). M&A transactions, therefore, provide a lot of uncertainty for workers, especially regarding their fates in the organization or the future of the company.

Yan & Zhu (2013) also say that since M&A transactions may mean unstable transitions, the feelings of the workers may be affected. Often, most workers are more loyal to their careers than to their organizations; therefore, whenever a merger or acquisition transaction threatens their careers, they are more likely to frustrate it (Yan & Zhu, 2013). The attitudes and motivation of the workers are important factors to consider in evaluating the success of M&A transactions because their activities are the binding forces that outline the successful integration of organizational activities. Indeed, most M&A transactions aim to acquire knowledge and knowledge workers. Therefore M&A contracts are bound to affect psychological contracts between employees and their companies. Since the psychological contracts that different companies have with their employees contain different sets of beliefs about mutual obligations, it is inevitable for any contract violation to affect the level of trust that the employees may have with the employer (Yan & Zhu, 2013).

Usually, when a merger or acquisition occurs, new employees may experience conquests or similar tussles in their new job environment because new and old job employees may form hostile workgroups that distrust one another. The outcome of such distrust may be disastrous if the new knowledge workers consider there is a psychological contract violation because they may eventually distrust the organization altogether. If this distrust persists, it may affect other groups in the organization, thereby affecting interpersonal trust within the organization (Yan & Zhu, 2013).

The influence that M&A transactions have on interpersonal trust has been rarely investigated by researchers because most researchers have only analyzed the extent that M&A transactions lead to psychological contract violations. Nonetheless, Yan & Zhu (2013) say that there is still hope for organizations if they experience such mistrusts in the organization. For example, they may use appropriate human resource practices to manage such distrusts, especially because their intentions in the merger may not necessarily be the perception created among the employees.

Competence and Commitment of Project Manager

Several researchers have said that the competence and commitment of a project manager to a merger or acquisition process are critical for the success of the merger or acquisition (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). The competence and commitment of team members also surface in the same context as an important factor that influences the success of M&A transactions. However, the competence and commitment of a team member are unequal to the importance of the project manager’s commitment to the merger or acquisition. Therefore, if the team members are highly competent and committed to a merger or acquisition, the lack of commitment by the project manager may still fail the process.

A manager’s commitment to a project may manifest through the evaluation of different factors, such as his ability to motivate team members to succeed, his ability to coordinate different project activities, and his ability to organize project tasks. The commitment of the project manager should suffice throughout all stages of the merger or acquisition process. The project manager should also demonstrate that he/she is deeply committed to achieving the goals of the merger or acquisition. Relative to this assertion, Hoang & Kamolrat (2008) claim “the project manager should be people-oriented, result-oriented, diplomatic, and hard driving” (p. 59).

The competence and skills of project managers often revolve around the management of human interactions because several researchers believe that project managers mainly have to handle human aspects of project management, such as manager-client interaction and communications with the target firm (and the likes). For example, a common skill that many researchers identify as an important factor to consider in project management is negotiation skills. The inclusion of such skills as part of a manager’s competence shows that negotiation skills are important in closing merger and acquisition deals. The same skills are crucial in realizing customer satisfaction, especially because the project manager may use the same skills to bargain for better terms and conditions that favor the client during a merger or acquisition deal (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). Above all, there is little contradiction among researchers regarding the importance of recruiting project managers who have a wealth of experience regarding mergers and acquisitions (Hoang & Kamolrat, 2008). Many researchers, therefore, hold the view that a merger or acquisition process needs to be overseen by people who have the necessary skills and competence to undertake such a process. Essentially, the skills and competence of the staff should both be perceived as important prerequisites for the success of a merger or acquisition project.

Cultural Integration

A common school of thought that has been touted by many researchers, as a possible reason for the high failure rate of M&A transactions, is the belief that many companies wrongly focus on the financial rewards of M&A transactions (Lau et al., 2012). Specifically, researchers who share this school of thought posit that the ignorance of non-financial factors, social factors, and cultural factors in M&A transactions inform the high number of M&A failures. It is from this basis that cultural integration emerges as a critical success factor for mergers and acquisitions.

Deloitte Development (2009) says the failure to integrate different cultures during a cross-border merger or acquisition process creates a strong force that could counter the value-creating outcome that often characterizes mergers and acquisitions. Deloitte Development (2009) mentions one study which showed that about 30% of all failed mergers and acquisitions stem from improper cultural integration. Certainly, companies that experience improper cultural integration find it difficult to formulate effective decisions or operate their departments efficiently (during mergers and acquisition processes). Before divulging the details surrounding cultural integration as a critical success factor, it is important to understand culture as a set of beliefs, values, and assumptions that inform peoples’ attitudes and work practices. Since culture is implicit, it is often difficult for people who share the same cultural background to criticize their culture or understand how their cultures inhibit them. Usually, only people who come from outside the sphere of cultural understanding may effectively understand the inhibitions that a specific culture may pose to an organization (Deloitte Development, 2009).

The main reason why culture affects the success of a merger or acquisition is its ability to influence peoples’ perceptions and understanding of their actions in the organization. It is therefore easy to understand why cultural beliefs lead people to believe that their actions are right, even when the actions may not make sense to them in the first place. The effect of a bad cultural influence is often difficult to eliminate because cultures are often resilient. Therefore, unlike other organizational influences that may manifest as products of “trends,” cultural influences are normally long-standing. The resilience of culture often stems from its implicit nature (indeed, it is difficult for people to comprehend why their cultures may be wrong, or how they exert negative influences on their organizational actions).

Deloitte Development (2009) explains the effect of culture on mergers and acquisitions by arguing that most mergers and acquisitions would be successful if people reasoned logically. However, people do not always base their actions on rational decisions alone; their shared cultural beliefs and individual personalities also affect their actions. Culture significantly underpins these effects. Based on this understanding, the impact of cultural integration in mergers and acquisitions is expansive.

The impact of cultural effects on the performance of a merger or acquisition manifests in different ways, depending on the nature of cultural influence. Deloitte Development (2009) explains that culture influences decision-making styles, leadership styles, how people work together, the beliefs regarding personal success, and an employees’ ability to change. These factors eventually affect the performance of a merger or acquisition contract. For example, if a manager operates in a culture that prefers a top-down decision-making style, effective integration in the organization will mainly depend on the manager’s effective decision-making skills. Similarly, in this cultural environment, the decision-making style may affect the ability to make and implement decisions (Deloitte Development, 2009). Through the same lens of analysis, it is correct to say that cultural influences may similarly affect the decision-making process of an organization, such as dictatorial or democratic leadership styles. This analogy is especially true for valuable employees in the organization because their labor mobility is often high (Deloitte Development, 2009). High labor mobility is often undesirable for mergers and acquisition processes because the loss of intellectual talent may significantly undermine the value of a merger or acquisition.