Pathophysiology

Asthma is typically defined as a chronic disease that affects the patient’s airways, impeding the process of breathing (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2014). The understanding of how asthma is developed and by what factors it is triggered has been altered significantly over the past few years. At present, the pathophysiology of the disease is rather intricate since several conditions have been identified as the leading causes of asthma.

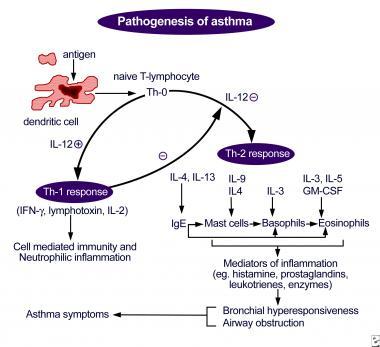

For instance, “Bronchospasms, edema, excessive mucus, and epithelial and muscle damage” (Lynn & Kushto-Reese, 2015, p. 49) are typically viewed as the key contributors to asthma development in patients (Lynn & Kushto-Reese, 2015). Each of the conditions listed above causes the development of bronchoconstriction with bronchospasms, therefore, making airways narrow (Lynn & Kushto-Reese, 2015). As a result, the premises for an asthma attack are created (see Figure 1).

It should be borne in mind, though, that the degree of disease variation in patients hinges on not the symptoms but the age thereof, as a recent study indicates (Kudo, Ishigatsubo, & Aoki, 2013). For instance, in children under 6, the development of the disease is typically preceded by the asthma-like symptoms that manifest themselves roughly at the age of three (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017).

A deficit in lung function can be observed in the identified group of patients at the age of 11-16. The force expiratory volume, however, remains consistent. The observations mentioned above are strikingly different from the ones carried out in a group of children that developed asthma after the age of three. Particularly, the specified patients did not show the propensity toward the development of lung function deficit (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2014).

Genomic Issues

Asthma is currently viewed as a disease induced by both environmental and genetic factors. Therefore, understanding the genomic characterization of the disease is crucial to its management. Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) carried out lately indicate that the PGAP3 gene, or PERLD1, defines the development of asthma in patients (Li et al., 2013).

It should be noted, though, that there are uncertainties in the current research on the subject of genomes and asthma. For instance, a recent analysis of the issue shows that, while PGAP3 has a tangible effect on the development of allergic reactions to specific elements, it is GSDMB that determines the propensity toward the disease development in patients: “STARD3/PGAP3 may act on the allergic component of asthma while the GSDMB/ORMDL3/GSDMA locus may mediate its effect by a shared mechanism acting on most forms of asthma” (Lavoie-Charland, Berube, Boulet, & Bosse, 2016, p. 909). Therefore, there are at least two genomes that possibly cause the development of asthma in patients (Lavoie-Charland et al., 2016).

A whole-blood expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) used in the research conducted by aaa showed that the functional variants of 17q12-21 are also associated with the development of allergic reactions toward a set of specific irritants (Andiappan et al., 2016). It is remarkable, though, that 17q12-21 affects the development of allergic asthma yet not rhinitis (Andiappan et al., 2016). Particularly, there is a connection between the genes at 17q12-21 and the polymorphism rs8076131 (Andiappan et al., 2016).

It should be borne in mind, though, that rs8076131 is not the only polymorphism that is associated with asthma. The article written by Schedel et al. (2015) shows that rs4065275, as well as the group of polymorphisms within ORMDL3, in general, is linked directly to the TH2 cytokines levels and, therefore, affects the susceptibility to asthma, especially among children (Schedel et al., 2015). However, further studies of the identified connection, as well as how the genomes in question affect the development of the disease, is required.

Literature Review

Seeing that asthma cannot be cured completely, the current approaches to managing it are aimed primarily at reducing the symptoms (e.g., coughing, shortness of breath, etc.) and improving the patients’ quality of life. At present, active engagement of patients and, if needed, their parents or legal guardians in the process of managing the disorder is viewed as a necessity. For the people that are capable of taking care of themselves, the promotion of patient independence is considered a crucial step in addressing the adverse effects of asthma successfully (Jain et al., 2014).

Two primary types of asthma treatment are utilized presently. These are short-term relievers (bronchodilators, particularly, dry powder inhalers and nebulizers (Daley-Yates, Mehta, Chan, Despa, & Louey, 2014)) and long-term disease control medications (Loymans et al., 2014).

Among the former, corticosteroids that are administered orally or intravenously are typically listed. Short-term relievers, which include bronchodilators, are used for three primary goals, i.e., the relaxation of the smooth muscle by stimulating beta-2 receptors, prevention of the cholinergic nerves activation, and cessation of the phosphodiesterase (PDE) enzymes’ functioning so that the further dilation of the bronchial airways could be possible (Normansell & Welsh, 2015). Long-term medication, in turn, also include corticosteroids (e.g., budesonide, beclomethasone, fluticasone, etc.). Apart from corticosteroids, leukotriene modifiers (zileuton, montelukast, etc.) are used to reduce the threat of an asthma attack (Lajqi, Ilazi, Kastrati, & Islami, 2015).

Data Collection

Approach

To gather the essential information about asthma, its development, and treatment, as well as other issues associated with the disease, an overview of the recent studies and the databases that contained the general information about asthma was required. Therefore, a literature review was used as the primary approach to data collection and its further interpretation so that it could be utilized in the study. As a result, a comprehensive review of the available information became possible.

Keywords

Searching for the relevant data required using specific keywords. It should be noted, though, that the information about different aspects of the disease had to be utilized in the research. Therefore, different sets of keywords were used for each of the search processes.

Table 1. Keywords used in the Search Process.

Databases

In the course of the search, ResearchGate and NCBI were used as the key databases for locating the essential information. The two resources were selected because they provide academic, peer-reviewed, and credible articles. Less trustworthy databases were discarded.

Electronic Clinical Tools

No electronic clinical tools were utilized in the research. Since there was no need for a quantitative study, including the information from HER provided by local healthcare facilities did not seem necessary. Instead, an all-embracive analysis of the articles obtained from scholarly databases was conducted.

Clinical Guideline for Asthma Management

At present, the U.S. standards for asthma management are defined by the guide provided by the NCBI in 2007 (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2007). Even though the identified resource is comparatively old, it remains the basis for the diagnosis and management of asthma. The guide provides detailed information about the nature of the problem, its pathophysiology, and the available treatment methods.

The guide places an especially strong emphasis on the importance of patient education as the path to successful management of the disease: “Asthma self-management education should be integrated into all aspects of asthma care, and it requires repetition and reinforcement” (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2007, p. 93). The identified guideline should be improved and followed closely nowadays by introducing social media into the process of patient education as the means of keeping the target population updated on the latest information and promoting cooperation between a nurse and the community.

For instance, engaging asthma patients in a dialogue by encouraging them to participate in Facebook discussions of the problem and responding to the information posted by the healthcare services will be a crucial step on the way to improving the management of asthma. Furthermore, a range of myths about asthma will be debunked. As a result, patients will feel empowered for developing independence in identifying asthma-related symptoms and searching for the assistance of healthcare experts (Panzera et al., 2013).

Treatment Approaches

As stressed above, the complete treatment of asthma is impossible at present; instead, its consistent management is used to improve the quality of the patient’s life (Jain et al., 2014). Therefore, an approach to handling the disorder in a long-term perspective needs to be considered. Furthermore, one must keep in mind that there are treatment strategies for three stages of asthma development (i.e., the so-called green, yellow, and red zones) (Yin et al., 2012). For this purpose, the stepwise approach must be used (Inoue et al., 2017). A common treatment framework implies carrying out the following steps:

- Identifying the severity of the problem (i.e., either a green, yellow, or red zone stage);

- Providing the patient with a quick-relief medication, if necessary (Albuterol, Levalbuterol, Metaproterenol, or Terbutaline) (U.S. National Library of Medicine, 2017);

- Expectorating the secretions of the patient so that the further aggravation of the problem could be avoided;

- Maintaining the airway clean so that the necessary medications could be administered to the patient;

- Continuing to provide long-term medications such as dry powder inhalers and nebulizers (1-2 puffs a day) if the short-term medication is efficient;

- Educating the patient about the symptoms, the necessity to avoid the allergens, the need to use the provided medications (1-2 puffs of nebulizers per day), etc. (Inoue et al., 2017).

Alternative treatment approaches may involve the use of fluid therapy (in case of a patient experiences dehydration) and pharmacologic therapy, which allows determining the patient’s response to medications (Bendjelid, Rex, Scheeren, & Critchley, 2015). However, the plan outlined above creates premises for all-embracive management of asthma and, thus, should be viewed as the superior one.

Best Approach: Selection and Rationale

As stressed above, the framework involving the classification of the asthma attack severity and the identification of the patient’s age (i.e., the stepwise approach) allows for the best results. The reason for choosing the specified strategy as the most efficient one is that it helps determine the patients’ needs fast and accurately. As a result, the chances for a patient outcome increase greatly (Inoue et al., 2017).

The use of fluid therapy, while also being quite effective, cannot be seen as an independent strategy for managing asthma since it does not include the comprehensive model that can be used to assist any asthma patient. Instead, it can only be utilized in specific cases of certain asthma severity. Therefore, it cannot be viewed as the ultimate tool for handling asthma cases (Bendjelid et al., 2015).

Consequently, the stepwise approach must be considered the most effective tool. It produces an immediate result and contributes to a massive improvement in the patient’s condition. Furthermore, the identified framework helps monitor asthma in patients of any age, from newborns to adults. The fact that the strategy allows for a minimum of adverse effects should also be considered one of its primary advantages (Inoue et al., 2017). Thus, it should be used as the basis for handling asthma cases.

Follow-up Treatment and Referrals

The further management of the case involves educating the patient about asthma and its management. Particularly, independence must be encouraged. The patient must be able to identify the symptoms that may pose a threat to their well-being and contact the healthcare services. Patient referrals must be considered a necessity in case of an asthma episode exacerbation. Subsequent tests carried out by an immunologist are obligatory for the further analysis of the problem and the identification of the possible treatment options. Furthermore, patient education must follow the treatment process so that further instances of asthma could be addressed efficiently.

References

Andiappan, A. K., Sio, Y. Y., Lee, B., Suri, B. K., Matta, S. A., Lum, J., … Chew, F. T. (2016). Functional variants of 17q12-21 are associated with allergic asthma but not allergic rhinitis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 137(3), 758-766. Web.

Asthma: Practice essentials, background, anatomy. (2017). Web.

Bendjelid, K., Rex, S., Scheeren, T., & Critchley, L. (2015). Year in review in journal of clinical monitoring and computing 2014: Cardiovascular and hemodynamic monitoring. Journal of Clinical Monitoring and Computing, 29(2), 203-207. Web.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017). Learn how to control asthma. Web.

Daley-Yates, P. T., Mehta, R., Chan, R. H., Despa, S. X., & Louey, M. D. (2014). Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of fluticasone propionate and salmeterol delivered as a combination dry powder from a capsule-based inhaler and a multidose inhaler in asthma and COPD patients. Journal of Aerosol Medicine and Pulmonary Drug Delivery, 27(4), 279-289. Web.

Inoue, H., Nagase, T., Morita, S., Yoshida, A., Jinnai, T., & Ichinose, M. (2017). Prevalence and characteristics of asthma–COPD overlap syndrome identified by a stepwise approach. International Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, 12(1), 1803-1810. Web.

Jain, V. V., Allison, R., Beck, S. J., Jain, R., Mills, P. K., Mccurley, J. W., … Peterson, M. W. (2014). Impact of an integrated disease management program in reducing exacerbations in patients with severe asthma and COPD. Respiratory Medicine, 108(12), 1794-1800. Web.

Kudo, M., Ishigatsubo, Y., & Aoki, I. (2013). Pathology of asthma. Frontiers in Microbiology, 4(263), 1-16. Web.

Lajqi, N., Ilazi, A., Kastrati, B., & Islami, H. (2015). Comparison of Glucocorticoid (Budesonide) and Antileukotriene (Montelukast) effect in patients with bronchial asthma determined with body plethysmography. Acta Informatica Medica, 23(6), 347-351. Web.

Lavoie-Charland, E., Berube, J. C., Boulet, L. P., & Bosse, Y. (2016). Asthma susceptibility variants are more strongly associated with clinically similar subgroups. Journal of Asthma, 53(9), 907-13. Web.

Li, L., Kabesch, M., Bouzigon, E., Demenais, F., Farrall, M., Moffatt, M. F., … Liang, L. (2013). Using eQTL weights to improve power for genome-wide association studies: A genetic study of childhood asthma. Frontiers in Genetics, 4(103), 1-14. Web.

Loymans, R. J., Gemperli, A., Cohen, J., Rubinstein, S. M., Sterk, P. J., Reddel, H. K., … Riet, G. T. (2014). Comparative effectiveness of long term drug treatment strategies to prevent asthma exacerbations: Network meta-analysis. BMJ, 348(1), 1-16. Web.

Lynn, S. J., & Kushto-Reese, K. (2015). Understanding asthma pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management Learn about new research findings and current treatment strategies for this common disorder. American Nurse Today, 10(7), 49-51.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2007). Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma (EPR-3): Full report. Web.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2014). What is asthma? Web.

Normansell, R., & Welsh, E. (2015). Asthma can take over your life but having the right support makes that easier to deal with. Informing research priorities by exploring the barriers and facilitators to asthma control: A qualitative analysis of survey data. Asthma Research and Practice, 1(1), 11-21. Web.

Panzera, A. D., Schneider, T. K., Martinasek, M. P., Lindenberger, J. H., Couluris, M., Bryant, C. A., & Mcdermott, R. J. (2013). Adolescent asthma self-management: Patient and parent-caregiver perspectives on using social media to improve care. Journal of School Health, 83(12), 921-930. Web.

Schedel, M., M., S., Gaertner, V. D., Toncheva, A. A., Depner, M., Binia, A., … Kabesch, M. (2015). Polymorphisms related to ORMDL3 are associated with asthma susceptibility, alterations in transcriptional regulation of ORMDL3, and changes in TH2 cytokine levels. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 136(4), 758-768. Web.

U.S. National Library of Medicine. (2017). Asthma – Quick-relief drugs. Web.

Yin, H. S., Gupta, R. S., Tomopoulos, S., Wolf, M. S., Mendelsohn, A. L., Antler, L., … Dreyer, B. P. (2012). Readability, suitability, and characteristics of asthma action plans: Examination of factors that may impair understanding. Pediatrics, 131(1), 118-128. Web.